Poor Prognosis in Warfarin-Associated Intracranial

Anuncio

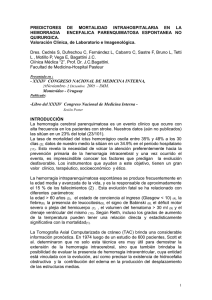

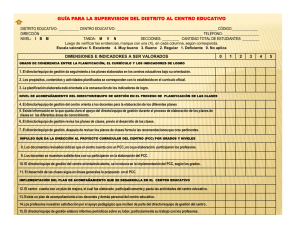

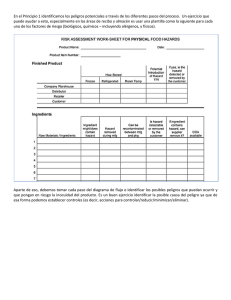

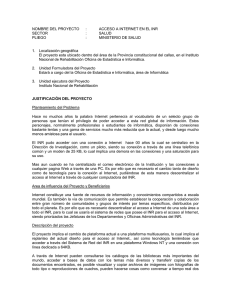

Poor Prognosis in Warfarin-Associated Intracranial Hemorrhage Despite Anticoagulation Reversal Dar Dowlatshahi, MD, PhD; Kenneth S. Butcher, MD, PhD; Negar Asdaghi, MD, MSc; Susan Nahirniak, MD; Manya L. Bernbaum, BSc; Antonio Giulivi, MD; Jason K. Wasserman, MD, PhD; Man-Chiu Poon, MD; Shelagh B. Coutts, MD; on behalf of the Canadian PCC Registry (CanPro) Investigators* Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 17, 2016 Background and Purpose—Anticoagulant-associated intracranial hemorrhage (aaICH) presents with larger hematoma volumes, higher risk of hematoma expansion, and worse outcome than spontaneous intracranial hemorrhage. Prothrombin complex concentrates (PCCs) are indicated for urgent reversal of anticoagulation after aaICH. Given the lack of randomized controlled trial evidence of efficacy, and the potential for thrombotic complications, we aimed to determine outcomes in patients with aaICH treated with PCC. Methods—We conducted a prospective multicenter registry of patients treated with PCC for aaICH in Canada. Patients were identified by local blood banks after the release of PCC. A chart review abstracted clinical, imaging, and laboratory data, including thrombotic events after therapy. Hematoma volumes were measured on brain CT scans and primary outcomes were modified Rankin Scale at discharge and in-hospital mortality. Results—Between 2008 and 2010, 141 patients received PCC for aaICH (71 intraparenchymal hemorrhages). The median age was 78 years (interquartile range, 14), 59.6% were male, and median Glasgow Coma Scale was 14. Median international normalized ratio was 2.6 (interquartile range, 2.0) and median parenchymal hematoma volume was 15.8 mL (interquartile range, 31.8). Median post-PCC therapy international normalized ratio was 1.4: 79.5% of patients had international normalized ratio correction (⬍1.5) within 1 hour of PCC therapy. Patients with intraparenchymal hemorrhage had an in-hospital mortality rate of 42.3% with median modified Rankin Scale of 5. Significant hematoma expansion occurred in 45.5%. There were 3 confirmed thrombotic complications within 7 days of PCC therapy. Conclusions—PCC therapy rapidly corrected international normalized ratio in the majority of patients, yet mortality and morbidity rates remained high. Rapid international normalized ratio correction alone may not be sufficient to alter prognosis after aaICH. (Stroke. 2012;43:00-00.) Key Words: acute care 䡲 acute Rx 䡲 anticoagulation 䡲 emergency medicine 䡲 intracerebral hemorrhage A nticoagulant-associated intracranial hemorrhage (aaICH) is predictive of larger hematoma volumes,1 higher rates of hematoma expansion, and worse clinical outcomes2 as compared with spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). The majority of patients with aaICH are at risk of hematoma expansion and require rapid reversal of anticoagulation. The current guidelines from the American Heart Association/ American Stroke Association, as endorsed by the American Academy of Neurology, support the use of either fresh-frozen plasma or prothrombin complex concentrate (PCC) for the Received January 25, 2012; final revision received March 12, 2012; accepted March 13, 2012. From the Department of Medicine (D.D.), Division of Neurology, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada; the Division of Neurology (K.S.B.) and the Division of Hematopathology (S.N.), University of Edmonton, Edmonton, Alberta, Canada; BC Centre for Stroke and Cerebrovascular Disease (N.A.), Division of Neurology, University of British Columbia, British Columbia, Canada; the Department of Clinical Neurosciences (M.L.B.), Seaman Family MR Centre, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canada; Hematolopathology and Transfusion Medicine (A.G.), Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Ottawa and The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Canada; Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (J.K.W.), University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canada; the Division of Hematology and Hematologic Malignancies (M.-C.P.), University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada; and the Department of Clinical Neurosciences and Radiology (S.B.C.), Hotchkiss Brain Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada. *CanPro Investigators: Dr K. Butcher (University of Alberta, Co-Primary Investigator); Dr S. Coutts (University of Calgary, Co-Primary Investigator); Dr D. Dowlatshahi (University of Ottawa, Co-Primary Investigator); Dr J. Bormanis (University of Ottawa, Site Investigator); Dr A. Giulivi (University of Ottawa, Site Investigator); Dr S. Jackson (University of Calgary, Site Investigator); Dr S. Nahimiak (University of Alberta, Site Investigator); Dr M.C. Poon (University of Calgary, Site Investigator); Dr M. Sharma (University of Ottawa, Site Investigator); Dr G. Stotts (University of Ottawa, Site Investigator); and Dr A. Tinmouth (University of Ottawa, Site Investigator). Correspondence to Dar Dowlatshahi, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Neurology, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, University of Ottawa, Ottawa Hospital Civic Campus, Room C2182, 1053 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1Y 4E9. E-mail ddowlat@ottawahospital.on.ca © 2012 American Heart Association, Inc. Stroke is available at http://stroke.ahajournals.org DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.652065 1 2 Stroke July 2012 Table 1. Baseline Demographics of the Registry Cohort n⫽141 Age, y (median 关IQR兴) Male sex (%) 78 关14兴 84 (59.6%) PMHx Presenting INR (median 关IQR兴) 2.6 关2兴 Indication for warfarin use Atrial fibrillation 106 (75%) Stroke 42 (29.8%) Atrial flutter 1 (0.7%) MI/CAD 43 (30.5%) Valvular heart disease 9 (6.4%) DVT/PE 18 (12.8%) Venous thrombosis 20 (14%) ICH 5 (3.5%) Ventricular dysfunction 1 (0.7%) SDH 4 (2.8%) APLA 1 (0.7%) SAH 4 (2.8%) Cardiac thrombus 1 (0.7%) Cryptogenic stroke 1 (0.7%) Dementia 17 (12.1%) Hypertension 82 (58.2%) Diabetes Hemorrhage type 37 (26.2%) IPH 71 (50.4%) 105 (74.5%) SDH 61 (43.3%) Congestive heart failure 25 (17.7%) SAH 8 (5.7%) Valvular heart disease 11 (7.8%) EDH Mechanical heart valve 16 (11.3%) Atrial fibrillation Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 17, 2016 Current smoker Antiplatelets Heparin 5 (3.5%) 1 (0.7%) 15.8 关31.8兴 Baseline IPH volume (median mL) IVH (%) 27 (19%) 28 (19.9%) Baseline mRS (median 关IQR兴) 1 关2兴‡ 3 (2.1%) Baseline GCS (median 关IQR兴) 14 关5兴§ Hb (median 关IQR兴) 133 关28兴* Platelets (median 关IQR兴) 224 关92兴* Glucose (median 关IQR兴) 7.1 关4兴† INR indicates international normalized ratio; IQR, interquartile range; PMHx, previous medical history; MI, myocardial infarction; CAD, coronary artery disease; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; SDH, subdural hemorrhage; SAH, subarachnoid hemorrhage; Hb, hemoglobin; APLA, antiphospholipid antibody syndrome; IPH, intraparenchymal hemorrhage; EDH, epidural hemorrhage; IVH, intraventricular hemorrhage; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale. *Missing 6 values. †Missing 17 values. ‡Missing 7 values. §Missing 22 values. urgent correction of international normalized ratio (INR) in patients with aaICH.3 These guidelines suggest PCC is a reasonable alternative to fresh-frozen plasma and may have fewer complications related to fluid overload. Although PCC therapy can rapidly correct INR4 and attenuate hematoma expansion in patients with aaICH,5 there are little data regarding safety and outcome after treatment. Randomized controlled trials of aaICH therapy are challenging to design, requiring large numbers of patients to detect modest treatment effects in the context of high baseline mortality and morbidity.6 With an aging population and increase in patients taking oral anticoagulants for atrial fibrillation, well-designed observational studies and treatment registries present an opportunity to understand the natural history of patients with aaICH treated with PCC. In response to the approval of the first PCC therapy in Canada in 2008, we launched a multicenter registry to monitor PCC use for aaICH with the goals of: (1) confirming its ability to rapidly correct INR in the emergency setting; (2) documenting all thrombotic events after therapy; and (3) assessing clinical outcome of a cohort of patients with aaICH treated with PCC. Methods The Canadian PCC Registry In 2008, Health Canada licensed its first PCC product, Octaplex, for urgent INR correction in patients receiving warfarin therapy. Canadian tertiary care regional stroke centers adopted institutional Octaplex infusion protocols for patients with ICHs in the context of elevated INR and known warfarin use. In November 2008, we launched the Canadian PCC Registry (CanPro) as a prospective inpatient registry of all consecutive patients treated with Octaplex at 3 tertiary care stroke centers (Calgary, Alberta; Edmonton, Alberta; and Ottawa, Ontario). On diagnosis of aaICH, patients presenting to these 3 participating institutions received Octaplex; the Blood Bank included the patient into the Registry once Octaplex was prepared and released. We subsequently collected clinical, imaging, and laboratory data from the medical records of patients within the Registry. Human research ethics boards at all 3 participating institutions approved the study and procedures were followed in accordance to institutional guidelines. Outcomes and Definitions Primary outcomes included INR correction, thrombotic events, and in-hospital mortality. Rapid INR correction was defined as an INR ⬍1.5 within 1 hour of PCC infusion. Adverse events included any thrombotic event diagnosed by the treating clinicians within 30 days of PCC infusion. Secondary outcomes included significant hema- Dowlatshahi et al Table 2. PCC Therapy in the Study Cohort Poor Prognosis in Warfarin-Associated ICH Table 3. Thrombotic Events Associated With PCC Therapy Onset to PCC treatment time (median 关IQR兴) 380 关420兴 min* Presentation to PCC treatment time (median 关IQR兴) 213 关244兴 min† Thrombotic Event Type CT to PCC treatment time (median 关IQR兴) 100 关137兴 min† Total PCC (Octaplex) dose (median 关IQR兴) Post-PCC INR (median 关IQR兴) Time from infusion to post-PCC INR (median 关IQR兴) INR ⬍1.5 within 1 h of PCC infusion (%) INR ⬍1.5 within 6 h of PCC infusion (%) Vitamin K administered (%) Time From PCC Infusion Warfarin Indication Ischemic stroke 21 d Atrial fibrillation 1000 U 关500兴 Ischemic stroke 5d Atrial fibrillation 1.4 关0.2兴 Ischemic stroke 1d Atrial fibrillation Atrial fibrillation DVT 30 d 56/78 (71.8%) DVT 21 d DVT 97/127 (76.4%) MI 28 d Atrial fibrillation MI 7d PE 54 min 关49兴 107 (85.6%)† FFP administered (%) 3 28 (22.4%)† Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 17, 2016 PCC indicates prothrombin complex concentrate; IQR, interquartile range; INR, international normalized ratio; FFP, fresh-frozen plasma. *Onset times were available in 88 patients (76% of intraparenchymal anticoagulant-associated intracranial hemorrhage had onset times, whereas only 54% of all other aaICH combined had onset times). †Sixteen missing values. toma expansion, defined as growth ⱖ6 mL or 33%7–9 and clinical outcome at discharge. The entire inpatient chart was reviewed for adverse events. We analyzed parenchymal hematoma volumes using computerized planimetry10,11 by readers blinded to clinical presentation and outcome. We measured clinical outcomes using the modified Rankin Scale; scores were generated based on chart reviews12 by investigators certified in modified Rankin Scale scoring. Based on prior studies and ongoing trials, we defined poor outcome as modified Rankin Scale 4 to 6.7–9,13 PCC indicates prothrombin complex concentrate; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; MI, myocardial infarction; PE, pulmonary embolism. received fresh-frozen plasma (Table 2). Median onset to treatment time was 380 minutes. Posttreatment INR was obtained within 1 hour in 78 of 141 (55.3%) patients and within 6 hours in 124 of 141 (87.9%) patients. INR correction ⬍1.5 was achieved in 71.8% at 1 hour and in 76.4% at 6 hours. In the patients with intraparenchymal aaICH, posttreatment INR was obtained within 1 hour in 39 of 71 (54.9%); INR correction ⬍1.5 was achieved in 28 of 39 (71.8%). Thrombotic Complications Thrombotic events associated with Octaplex use are listed in Table 3. Although the total 30-day thrombotic event rate was 5%, only 3 events occurred within 7 days of therapy (2%). Statistical Analysis We limited multivariable analysis of the predictors of poor outcome and mortality to the patients with intraparenchymal hemorrhage. We used univariate analyses to study associations between outcomes and age, sex, medical history, antithrombotic medications, baseline blood pressure, Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS), glucose, hemoglobin, INR, hematoma volume, intraventricular extension, Octaplex dose, onsetto-treatment time, fresh-frozen plasma use, rapid INR correction, and withdrawal of care. We used Fisher exact test for comparisons of dichotomous or categorical variables and t tests or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test for continuous variables. We subsequently built multivariable logistic regression models using candidate variables associated with the primary outcome (Pⱕ0.15) in the univariate analysis; nonsignificant variables (P⬎0.05) were eliminated in a backward stepwise fashion to create a minimal model with adjusted ORs. We used IBM SPSS 18.0 for Mac (Somers, NY) for all statistical analyses. Results Between November 2008 and October 2010, 141 consecutive patients received Octaplex for aaICH. Median age was 78 years (interquartile range, 14); 59.6% were male. Sixty-six (46.8%) patients had intraparenchymal hematoma (IPH), 59 (41.8%) had subdural hematoma with no parenchymal component, 15 (10.6%) had subarachnoid hemorrhage, and 1 (0.7%) had an isolated epidural hematoma (Table 1). Median presenting INR was 2.6 (interquartile range, 2.0). The most common indication for warfarin use was atrial fibrillation (75%). Octaplex Treatment and INR Patients were treated with a median Octaplex dose of 1000 IU (interquartile range, 500; based on Factor IX equivalence); 85.6% of patients received vitamin K, and 22.4% also Patients With IPH Of 71 patients with IPH, 33 (46.5%) had a follow-up CT. Of these, 15 (45.5%) had hematoma expansion ⬎6 mL or a 33% increase in volume (Table 4; Figure). Mortality rates and poor clinical outcome were highest among the IPH group (Table 5). Exploratory univariate analysis revealed patients with hematoma expansion ⬎6 mL or 33% had significantly higher mortality rates as compared with those without (66.7% versus 22.2%; P⫽0.015). In the patients with IPH, univariate analyses revealed associations between mortality and low GCS (Z⫽⫺3.4, P⫽0.001), larger baseline parenchymal hematoma volume (t⫽1.61, P⫽0.112), baseline total hematoma volume (ventricular⫹parenchymal; t⫽⫺2.64, P⬍0.010), shorter onset-totreatment times (t⫽2.46, P⫽0.017), and palliation (P⬍0.001). Similarly, exploratory analyses revealed associations between poor functional outcome and low GCS (Z⫽⫺3.09, P⫽0.002), baseline total hematoma volume (t⫽⫺1.607, P⫽0.113), history of congestive heart failure (P⫽0.06), shorter onset-to-treatment times (t⫽2.96, P⫽0.005), and palliation (P⬍0.001). Because Table 4. Baseline and Follow-Up Intraparenchymal Hematoma Volumes No. Median (IQR) Baseline IPH volume, mL 68 15.8 (31.8) Follow-up IPH volume, mL 33 16.8 (36) IPH growth ⬎33% or ⬎6 mL (%) Time to follow-up CT 15/33 45.5% 19 22 hr 41 min (13.75 hr) IQR indicates interquartile range; IPH, intraparenchymal hematoma. 4 Stroke July 2012 Figure. Significant hematoma growth despite INR correction with PCC. The patient was treated with 1000 U of PCC and 10 mg vitamin K 98 minutes after baseline CT scan. Repeat INR was 1.3 42 minutes after PCC treatment and 1.2 the next day. INR indicates international normalized ratio; PCC, prothrombin complex concentrate. Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 17, 2016 total hematoma volume and parenchymal hematoma volume are collinear, total hematoma volume was used in the multivariable models because it had a more robust association with mortality. After multivariable regression analysis, only low GCS (adjusted OR, 0.79 per point; 95% CI, 0.64 – 0.98; P⫽0.032) and palliation (adjusted OR, 43.01; 95% CI, 4.87–379.71; P⫽0.001) were independently associated with mortality. Low GCS was also associated with poor clinical outcome (adjusted OR, 0.678 per point; 95% CI, 0.50 – 0.91; P⫽0.009). All palliated patients had poor clinical outcome; therefore, this variable was excluded from the model. Discussion In a prospective multicenter registry of patients with aaICH, we found PCC therapy reversed anticoagulation in 71.8% of patients within 1 hour of treatment. This was associated with a 2% thrombotic event rate over 7 days. Nevertheless, mortality rates remained high and clinical outcomes were generally poor despite correction of the coagulopathy. The majority of patients had a repeat INR within 6 hours of therapy; 23.6% failed to reach the target INR ⬍1.5 at that point, which may reflect the lower dose of PCC used during the study period. This may have subsequently contributed to the high rate of poor outcomes. The median dose in our study was 1000 U based on a 2008 recommendation by the National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products to initiate therapy with this dose and supplement further if correction Table 5. Outcome by aaICH Classification Intracranial Hemorrhage Type No. In-Hospital Mortality* Discharge mRS (Median 关IQR兴)† Intraparenchymal 71 30 (42.3%) 5 关3兴‡ Subdural 61 21 (34.4%) 3 关4兴§ Epidural 1 0 3 Subarachnoid 8 1 (12.5%) 3 关3兴 aaICH indicates anticoagulant-associated intracranial hemorrhage; mRS, modified Rankin Scale; IQR, interquartile range. *P⫽0.3. †P⫽0.012. ‡mRS missing in 9. §mRS missing in 2. was inadequate 15 minutes after infusion.14 This is lower than the manufacturer’s recommendations, which are weight- and INR-based (starting at 1000 U for 70 kg at INR 2.0, to a maximum dose of 3000 U). The National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products has since revised and increased their dosing recommendations to an INR-based approach after a 2010 use review (1000 U for INR ⬍3.0, 2000 U for INR 3–5, and 3000 U for INR ⬎5).15 There were a total of 7 thrombotic events in the 30 days after PCC therapy. Three were ischemic strokes, which may have been related to the underlying untreated atrial fibrillation, 1 was an extension of a prior deep vein thrombosis, and 1 was a myocardial infarction in the context of untreated pulmonary embolism. Although we cannot completely exclude a causal relationship between PCC therapy and thrombotic events, the rate of adverse events was relatively low and potentially related to the original indication for anticoagulation. Our low adverse event rate is similar to that of 2 prior studies using the same PCC formulation,16,17 but we acknowledge that subclinical thrombotic events can be missed in the absence of a systematic screening protocol.18 We observed a 42.3% mortality rate in patients with intraparenchymal aaICH after PCC therapy, which is lower than the 62% and 67% reported in 2 recent aaICH studies2,6 and closer to the mortality rates associated with noncoagulopathic ICH.19 –21 Although indirect comparisons are not valid, these data are consistent with the hypothesis that INR correction shifts the expected outcome of an aaICH to that of a noncoagulopathic ICH, which is nevertheless clinically devastating. We also observed worse clinical outcomes in patients with IPH as compared with those with other hemorrhage types, although the mortality differences were not statistically significant. This may reflect differences in secondary surgical or medical management between hemorrhage types and warrants further exploration. Surprisingly, we did not find that shorter onset-totreatment time had a positive effect on clinical outcome. This may be due to missing onset times in 24% of the patients with intraparenchymal aaICH but more likely related to an interaction with the severity of neurological deficits, which was a robust predictor of mortality and poor outcome. Univariate Dowlatshahi et al Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 17, 2016 analysis suggested a relationship between shorter onset-totreatment times and poor outcomes, which became nonsignificant when GCS was added to the model. We postulate the process of care is expedited when patients with severe symptoms and low GCS present for emergency care, resulting in shorter treatment times but with paradoxically worse outcomes. Overall, our CT-to-treatment time was longer than ideal and measures must be implemented to rapidly reverse the coagulopathy in these patients. This is 1 potential mechanism for the overall relatively poor outcome in this study. Given the low thrombotic rate we found, allowing direct access to PCC in the emergency department for physicians treating these patients may speed up treatment times. Similarly, baseline hematoma volume was not associated with clinical outcome after covariate adjustment, which differs from a recent aaICH study suggesting volume is predictive of early (7-day) mortality and poor functional outcome.22 Some of the discrepancy may be related to volumetric measurement techniques; the latter study used the ABC/2 technique, which is known to both underestimate and overestimate large, irregular, and anticoagulant-associated hematomas,23–25 whereas we used computer-assisted planimetry specifically developed and validated for ICH measurement.10 However, a more likely explanation is that our statistical power was limited due to the relatively small sample of patients with IPH volumes in our study; the association with mortality detected in univariate analysis was possibly overshadowed by the robust effect of palliation and GCS. Interestingly, a recent study on early-care limitations after ICH also found the association between hematoma volume and mortality was highly attenuated when including withdrawal of care into the model (adjusted OR for volume, 1.01).26 Our study has a number of limitations; it was observational and lacked standardized follow-up CT scans, which precluded accurate assessment of hematoma expansion in the majority of patients. Therefore, there is potential for indication bias in those patients with follow-up CT scans; the scans may have been ordered in response to neurological worsening or suspected rebleeding. In addition, variability in timing of follow-up INRs complicated assessment of the time course of INR correction. We were also unable to comment on the hemorrhage etiology of our cohort and its potential interaction with INR correction and outcome. Finally, discharge modified Rankin Scale scores were derived from medical records, similar to prior observational studies.27,28 Nevertheless, our study has the advantage of consecutive enrollment from 3 independent tertiary care stroke centers and is 1 of the largest aaICH studies to date. Furthermore, we accounted for withdrawal of care effects, which are known to confound ICH outcomes.26,29,30 In summary, we found that PCC therapy rapidly corrected INR in the majority of patients with aaICH, yet mortality and morbidity rates remained high. These results suggest that outcomes after aaICH can be devastating even with a reversal strategy31 and highlight the need for controlled experimental studies for anticoagulant reversal such as the ongoing multicenter INR Normalization in Coumadin-Associated Intracerebral Haemorrhage randomized control trial.32 Poor Prognosis in Warfarin-Associated ICH 5 Sources of Funding Dr Dowlatshahi is supported by the JP Bickell Foundation and a University of Ottawa Department of Medicine Research Salary Award. Dr Butcher receives grant-in-aid and salary support from Alberta Innovates Health Solutions, the Canadian Institutes for Health Research, and holds a Canada Research Chair. Dr Coutts received salary support from Alberta-Innovates-Health solutions and the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada’s Distinguished Clinician Scientist award, supported in partnership with the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR), Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health, and AstraZeneca Canada Inc. M. Bernbaum received a Canadian Stroke Network summer studentship award for this work. Disclosures Dr Dowlatshahi has received speaker’s honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim and Octapharma and served on an advisory board for Bayer Canada. Dr Butcher has received speaker’s honoraria from Octapharma and served on advisory boards for Bayer Canada, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Pfizer/BMS. Dr Poon has served on advisory boards for Pfizer, Octapharma, and Novo Nordisk. Dr Giulivi has served on an advisory board for CSL Behring and Octapharma. Dr Nahirniak has served as the chair of the National Advisory Committee of Blood and Blood Products Prothrombin Complex Working Group. Dr Coutts has served on an advisory board for Pfizer/BMS. References 1. Flaherty ML, Tao H, Haverbusch M, Sekar P, Kleindorfer D, Kissela B, et al. Warfarin use leads to larger intracerebral hematomas. Neurology. 2008;71:1084 –1089. 2. Cucchiara B, Messe S, Sansing L, Kasner S, Lyden P, for the CHANT Investigators. Hematoma growth in oral anticoagulant related intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2008;39:2993–2996. 3. Morgenstern LB, Hemphill JC, Anderson C, Becker K, Broderick JP, Connolly ES, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2010; 41:2108 –2129. 4. Kalina M, Tinkoff G, Gbadebo A, Veneri P, Fulda G. A protocol for the rapid normalization of INR in trauma patients with intracranial hemorrhage on prescribed warfarin therapy. Am Surg. 2008;74:858 – 861. 5. Huttner HB, Schellinger PD, Hartmann M, Köhrmann M, Juettler E, Wikner J, et al. Hematoma growth and outcome in treated neurocritical care patients with intracerebral hemorrhage related to oral anticoagulant therapy: comparison of acute treatment strategies using vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma, and prothrombin complex concentrates. Stroke. 2006;37: 1465–1470. 6. Flaherty ML, Adeoye O, Sekar P, Haverbusch M, Moomaw CJ, Tao H, et al. The challenge of designing a treatment trial for warfarin-associated intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2009;40:1738 –1742. 7. STOP-IT Investigators. The spot sign for predicting and treating ICH growth study (STOP-IT). clinicaltrials.gov NCT00810888. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00810888. Accessed November 2011. 8. Dowlatshahi D, Demchuk AM, Flaherty ML, Ali M, Lyden PL, Smith EE, on behalf of the VISTA Collaboration. Defining hematoma expansion in intracerebral hemorrhage: relationship with patient outcomes. Neurology. 2011;76:1238 –1244. 9. Demchuk AM, Dowlatshahi D, Rodriguez-Luna D, Molina CA, Silva Blas Y, Dzialowski I, et al. Prediction of haematoma growth and outcome in patients with intracerebral haemorrhage using the CT-angiography spot sign (PREDICT): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2012; 11:307–314. 10. Kosior JC, Idris S, Dowlatshahi D, Alzawahmah M, Eesa M, Sharma P, et al. Quantomo: validation of a computer-assisted methodology for the volumetric analysis of intracerebral haemorrhage. Int J Stroke. 2011;6: 302–305. 11. Zimmerman RD, Maldjian JA, Brun NC, Horvath B, Skolnick BE. Radiologic estimation of hematoma volume in intracerebral hemorrhage trial by CT scan. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:666 – 670. 6 Stroke July 2012 Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 17, 2016 12. Hylek EM, Go AS, Chang Y, Jensvold NG, Henault LE, Selby JV, et al. Effect of intensity of oral anticoagulation on stroke severity and mortality in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1019 –1026. 13. Dowlatshahi D, Smith EE, Flaherty ML, Ali M, Lyden P, Demchuk AM, VISTA Collaborators. Small intracerebral haemorrhages are associated with less haematoma expansion and better outcomes. Int J Stroke. 2011; 6:201–206. 14. National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products. Recommendations for use of Octaplex威 in Canada. 2008. Available at: www.transfusion medicine.ca/news/publications/octaplex%C2%AE-recommendations-nac. Accessed March 12, 2012. 15. National Advisory committee on Blood and Blood Products. Recommendations for use of prothrombin complex concentrates in Canada. 2011. Available at: www.nacblood.ca/resources/guidelines/PCC.html. Accessed March 12, 2012. 16. Riess HB, Meier-Hellmann A, Motsch J, Elias M, Kursten FW, Dempfle CE. Prothrombin complex concentrate (Octaplex威) in patients requiring immediate reversal of oral anticoagulation. Thromb Res. 2007;121:9 –16. 17. Lubetsky A, Hoffman R, Zimlichman R, Eldor A, Zvi J, Kostenko V, et al. Efficacy and safety of a prothrombin complex concentrate (Octaplex威) for rapid reversal of oral anticoagulation. Thromb Res. 2004;113: 371–378. 18. Diringer MN, Skolnick BE, Mayer SA, Steiner T, Davis SM, Brun NC, et al. Thromboembolic events with recombinant activated factor VII in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: results from the Factor Seven for Acute Hemorrhagic Stroke (FAST) trial. Stroke. 2010;41:48 –53. 19. van Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, van der Tweel I, Algra A, Klijn CJ. Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:167–176. 20. Hemphill JC, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC. The ICH score: a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32:891– 897. 21. Broderick JP, Brott TG, Duldner JE, Tomsick T, Huster G. Volume of intracerebral hemorrhage. A powerful and easy-to-use predictor of 30-day mortality. Stroke. 1993;24:987–993. 22. Zubkov AY, Mandrekar JN, Claassen DO, Manno EM, Wijdicks EF, Rabinstein AA. Predictors of outcome in warfarin-related intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1320 –1325. 23. Divani AA, Majidi S, Luo X, Souslian FG, Zhang J, Abosch A, et al. The ABCs of accurate volumetric measurement of cerebral hematoma. Stroke. 2011;42:1569 –1574. 24. Wang CW, Juan CJ, Liu YJ, Hsu HH, Liu HS, Chen CY, et al. VolumeDependent overestimation of spontaneous intracerebral hematoma volume by the ABC/2 formula. Acta Radiol. 2009;50:306 –311. 25. Freeman WD, Barrett KM, Bestic JM, Meschia JF, Broderick DF, Brott TG. Computer-assisted volumetric analysis compared with ABC/2 method for assessing warfarin-related intracranial hemorrhage volumes. Neurocrit Care. 2008;9:307–312. 26. Zahuranec DB, Brown DL, Lisabeth LD, Gonzales NR, Longwell PJ, Smith MA, et al. Early care limitations independently predict mortality after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2007;68:1651–1657. 27. O’Donnell M, Oczkowski W, Fang J, Kearon C, Silva J, Bradley C, et al. Preadmission antithrombotic treatment and stroke severity in patients with atrial fibrillation and acute ischaemic stroke: an observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:749 –754. 28. Dowlatshahi D, Demchuk AM, Fang J, Kapral M, Sharma M, Smith EE. Association of statins and statin discontinuation with poor outcome and survival following intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2012;43:xxx–xxx. 29. Becker KJ, Baxter AB, Cohen WA, Bybee HM, Tirschwell DL, Newell DW, et al. Withdrawal of support in intracerebral hemorrhage may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. Neurology. 2001;56:766 –772. 30. Zahuranec DB, Morgenstern LB, Sánchez BN, Resnicow K, White DB, Hemphill JC. Do-not-resuscitate orders and predictive models after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2010;75:626 – 633. 31. Rizos T, Rohde S, Dörner N, Steiner T. Ongoing intracerebral bleeding despite hemostatic treatment associated with a spot sign in a patient on oral anticoagulation therapy. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28:623– 624. 32. Steiner T, Freiberger A, Griebe M, Hüsing J, Ivandic B, Kollmar R, et al. International normalised ratio normalisation in patients with coumarinrelated intracranial haemorrhages—the INCH trial: a randomised controlled multicentre trial to compare safety and preliminary efficacy of fresh frozen plasma and prothrombin complex—study design and protocol. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:271–277. Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 17, 2016 Poor Prognosis in Warfarin-Associated Intracranial Hemorrhage Despite Anticoagulation Reversal Dar Dowlatshahi, Kenneth S. Butcher, Negar Asdaghi, Susan Nahirniak, Manya L. Bernbaum, Antonio Giulivi, Jason K. Wasserman, Man-Chiu Poon and Shelagh B. Coutts on behalf of the Canadian PCC Registry (CanPro) Investigators Stroke. published online May 3, 2012; Stroke is published by the American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231 Copyright © 2012 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0039-2499. Online ISSN: 1524-4628 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/early/2012/05/03/STROKEAHA.112.652065 Data Supplement (unedited) at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/suppl/2016/04/10/STROKEAHA.112.652065.DC1.html Permissions: Requests for permissions to reproduce figures, tables, or portions of articles originally published in Stroke can be obtained via RightsLink, a service of the Copyright Clearance Center, not the Editorial Office. Once the online version of the published article for which permission is being requested is located, click Request Permissions in the middle column of the Web page under Services. Further information about this process is available in the Permissions and Rights Question and Answer document. Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at: http://www.lww.com/reprints Subscriptions: Information about subscribing to Stroke is online at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org//subscriptions/ Artículos originales Mal pronóstico de la hemorragia intracraneal asociada a warfarina a pesar de la reversión de la anticoagulación Dar Dowlatshahi, MD, PhD; Kenneth S. Butcher, MD, PhD; Negar Asdaghi, MD, MSc; Susan Nahirniak, MD; Manya L. Bernbaum, BSc; Antonio Giulivi, MD; Jason K. Wasserman, MD, PhD; Man-Chiu Poon, MD; Shelagh B. Coutts, MD; en nombre de los investigadores del Canadian PCC Registry (CanPro)* Antecedentes y objetivo—La hemorragia intracraneal asociada a anticoagulantes (HICaa) se caracteriza por un volumen de hematoma elevado, un mayor riesgo de expansión del hematoma y una evolución clínica peor que la de la hemorragia intracraneal espontánea. Los concentrados de complejo de protrombina (PCC) están indicados para la reversión urgente de la anticoagulación tras una HICaa. Dada la ausencia de evidencias sobre la eficacia basadas en ensayos controlados y aleatorizados, y la posibilidad de complicaciones trombóticas, el objetivo de este estudio fue determinar los resultados clínicos obtenidos en los pacientes con HICaa tratados con PCC. Métodos—Llevamos a cabo un registro prospectivo multicéntrico de los pacientes tratados con PCC por una HICaa en Canadá. Los pacientes fueron identificados por los bancos de sangre locales tras la autorización del PCC. Se utilizó una revisión de las historias clínicas para extraer los datos clínicos, de técnicas de imagen y de laboratorio, incluidos los episodios trombóticos después del tratamiento. Se determinaron los volúmenes de los hematomas en las TC cerebrales y las variables de valoración primarias fueron la escala de Rankin modificada en el momento del alta y la mortalidad intrahospitalaria. Resultados—Entre los años 2008 y 2010, un total de 141 pacientes recibieron tratamiento con PCC por una HICaa (71 hemorragias intraparenquimatosas). La mediana de edad fue de 78 años (rango intercuartiles, 14), un 59,6% eran varones, y la mediana de puntuación en la escala del coma de Glasgow fue de 14. La mediana de la ratio normalizada internacional fue de 2,6 (rango intercuartiles, 2,0) y la mediana de volumen del hematoma parenquimatoso fue de 15,8 mL (rango intercuartiles, 31,8). La mediana de la ratio normalizada internacional después del tratamiento con PCC fue de 1,4: el 79,5% de los pacientes presentaron una corrección de la ratio normalizada internacional (< 1,5) en el plazo de 1 hora con el tratamiento de PCC. Los pacientes con una hemorragia intraparenquimatosa presentaron una tasa de mortalidad intrahospitalaria del 42,3%, con una mediana de la escala de Rankin modificada de 5. Se produjo una expansión significativa del hematoma en el 45,5% de los casos. Hubo 3 complicaciones trombóticas confirmadas en los 7 días siguientes al tratamiento de PCC. Conclusiones—El tratamiento con PCC corrigió rápidamente la ratio normalizada internacional en la mayoría de los pacientes, aunque las tasas de mortalidad y morbilidad continuaron siendo altas. La corrección rápida de la ratio normalizada internacional por sí sola puede no ser suficiente para modificar el pronóstico después de la HICaa. (Traducido del inglés: Poor Prognosis in Warfarin-Associated Intracranial Hemorrhage Despite Anticoagulation Reversal Stroke. 2012;43:1812-1817.) Palabras clave: acute care n acute Rx n anticoagulation n emergency medicine n intracerebral hemorrhage Recibido el 25 de enero de 2012; revisión final recibida el 12 de marzo de 2012; aceptado el 13 de marzo de 2012. Department of Medicine (D.D.), Division of Neurology, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canadá; Division of Neurology (K.S.B.) y Division of Hematopathology (S.N.), University of Edmonton, Edmonton, Alberta, Canadá; BC Centre for Stroke and Cerebrovascular Disease (N.A.), Division of Neurology, University of British Columbia, British Columbia, Canadá; Department of Clinical Neurosciences (M.L.B.), Seaman Family MR Centre, University of Calgary, Calgary, Alberta, Canadá; Hematolopathology and Transfusion Medicine (A.G.), Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Ottawa and The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Canadá; Ottawa Hospital Research Institute (J.K.W.), University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Canadá; Division of Hematology and Hematologic Malignancies (M.-C.P.), University of Calgary, Calgary, Canadá; y Department of Clinical Neurosciences and Radiology (S.B.C.), Hotchkiss Brain Institute, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canadá. *Investigadores de CanPro: Dr. K. Butcher (University of Alberta, investigador coprincipal); Dr. S. Coutts (University of Calgary, investigador coprincipal); Dr D. Dowlatshahi (University of Ottawa, investigador coprincipal); Dr J. Bormanis (University of Ottawa, investigador de centro); Dr A. Giulivi (University of Ottawa, investigador de centro); Dr S. Jackson (University of Calgary, investigador de centro); Dr S. Nahimiak (University of Alberta, investigador de centro); Dr M.C. Poon (University of Calgary, investigador de centro); Dr M. Sharma (University of Ottawa, investigador de centro); Dr G. Stotts (University of Ottawa, investigador de centro); y Dr A. Tinmouth (University of Ottawa, investigador de centro). Remitir la correspondencia a Dar Dowlatshahi, MD, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Division of Neurology, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, University of Ottawa, Ottawa Hospital Civic Campus, Room C2182, 1053 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, Ontario, Canadá, K1Y 4E9. Correo electrónico ddowlat@ottawahospital.on.ca © 2012 American Heart Association, Inc. Puede accederse a Stroke en http://stroke.ahajournals.org 99 DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.652065 100 Stroke Noviembre 2012 Tabla 1. Características demográficas basales de la cohorte del registro n 141 Edad, años (mediana [RIC]) Sexo masculino (%) 78 [14] 84 (59,6%) HisPP INR inicial (mediana [RIC]) 2,6 2 Indicación para el uso de warfarina Fibrilación auricular Ictus 42 (29,8%) Flúter auricular IM/EC 43 (30,5%) Valvulopatías cardíacas TVP/EP 18 (12,8%) Trombosis venosa 106 (75%) 1 (0,7%) 9 (6,4%) 20 (14%) HIC 5 (3,5%) Disfunción ventricular 1 (0,7%) HSD 4 (2,8%) APLA 1 (0,7%) HSA 4 (2,8%) Trombo cardiaco 1 (0,7%) Demencia 17 (12,1%) Ictus criptogénico 1 (0,7%) Hipertensión 82 (58,2%) Diabetes 37 (26,2%) HIP 71 (50,4%) 105 (74,5%) HSD 61 (43,3%) 8 (5,7%) Fibrilación auricular Tipo de hemorragia Insuficiencia cardiaca congestiva 25 (17,7%) HSA Valvulopatías cardíacas 11 (7,8%) HED Válvula cardiaca mecánica 16 (11,3%) Fumador actual Antiagregantes plaquetarios Heparina 5 (3,5%) 1 (0,7%) Volumen basal de HIP (mediana, mL) 15,8 [31,8] HIV (%) 27 (19%) 28 (19,9%) mRS basal (mediana [RIC]) 1 2‡ 3 (2,1%) GCS basal (mediana [RIC]) 14 5 § Hb (mediana [RIC]) 133 28 * Plaquetas (mediana [RIC]) 224 92 * Glucosa (mediana [RIC]) 7,1 4 † INR indica ratio normalizada internacional; RIC, rango intercuartiles; HisPP, antecedentes patológicos previos; IM, infarto de miocardio; EC, enfermedad coronaria; TVP, trombosis venosa profunda; EP, embolia pulmonar; HIC, hemorragia intracraneal; HSD, hemorragia subdural; HSA, hemorragia subaracnoidea; Hb, hemoglobina; APLA, síndrome de anticuerpos antifosfolípidos; HIP, hemorragia intraparenquimatosa; HED, hemorragia epidural; HIV, hemorragia intraventricular; mRS, escala de Rankin modificada; GCS, escala del coma de Glasgow. *6 valores no disponibles. †17 valores no disponibles. ‡7 valores no disponibles. §22 valores no disponibles. L a hemorragia intracraneal asociada al uso de anticoagulantes (HICaa) predice un mayor volumen del hematoma1, unas tasas más elevadas de expansión del hematoma y una peor evolución clínica2 en comparación con lo que ocurre en la hemorragia intracerebral (HIC) espontánea. La mayoría de los pacientes con HICaa presentan un riesgo de expansión del hematoma y requieren una rápida reversión de la anticoagulación. Las guías actuales de American Heart Association/ American Stroke Association, que han sido avaladas por la American Academy of Neurology, respaldan el uso de plasma fresco congelado o de concentrado de complejo de protrombina (PCC) para la corrección urgente de la ratio normalizada internacional (INR) en los pacientes con HICaa3. Estas guías sugieren que el empleo de PCC es una alternativa razonable al uso de plasma fresco congelado y puede comportar menos complicaciones relacionadas con la sobrecarga de líquidos. Aunque el tratamiento con PCC puede corregir rápidamente la INR4 y atenuar la expansión del hematoma en los pacientes con HICaa5, existen pocos datos sobre su seguridad y la evolución clínica después del tratamiento. Los ensayos controlados y aleatorizados del tratamiento de la HICaa plantean dificultades de diseño, al requerir un elevado número de pacientes para detectar efectos terapéuticos modestos en el contexto de una mortalidad y morbilidad basales elevadas6. Con el aumento de la edad de la población y el incremento del número de pacientes tratados con anticoagulantes orales por una fibrilación auricular, los estudios observacionales bien diseñados y los registros de tratamiento brindan la oportunidad de conocer la evolución natural de los pacientes con HICaa tratados con PCC. Coincidiendo con la autorización del primer tratamiento de PCC en Canadá en 2008, pusimos en marcha un registro multicéntrico para llevar a cabo un seguimiento del uso de PCC para la HICaa con los siguientes objetivos: (1) confirmar su capacidad de corregir rápidamente la INR en un contexto de urgencia; (2) documentar todos los episodios trombóticos después del tratamiento; y (3) evaluar los resultados clínicos en una cohorte de pacientes con HICaa tratados con PCC. Dowlatshahi y cols. Mal pronóstico de la hemorragia intracraneal asociada a warfarina 101 Tabla 2. Tratamiento con PCC en la cohorte del estudio Tiempo desde inicio hasta tratamiento con PCC (mediana [RIC]) 380 [420] min* Tiempo desde presentación hasta tratamiento con PCC (mediana [RIC]) 213 [244] min† Tiempo desde TC hasta tratamiento con PCC (mediana [RIC]) 100 [137] min† Dosis total de PCC (Octaplex) (mediana [RIC]) INR post-PCC (mediana [RIC]) 1.000 U [500] 1,4 [0,2] Tabla 3. Episodios trombóticos asociados al tratamiento con PCC Tiempo a partir de la infusión de PCC Indicación para el uso de warfarina Ictus isquémico 21 d Fibrilación auricular Ictus isquémico 5d Fibrilación auricular Ictus isquémico 1d Fibrilación auricular 30 d Fibrilación auricular Tipo de episodio trombótico TVP Tiempo desde infusión hasta INR post-PCC (mediana [RIC]) 54 min [49] TVP 21 d TVP INR < 1,5 en el plazo de 1 h tras la infusión de PCC (%) 56/78 (71,8%) IM 28 d Fibrilación auricular INR < 1,5 en el plazo de 6 h tras la infusión de PCC (%) 97/127 (76,4%) IM 7d EP Administración de vitamina K (%) Administración de FFP (%) 107 (85,6%)† 28 (22,4%)† PCC indica concentrado de complejo de protrombina; RIC, rango intercuartiles; INR, ratio normalizada internacional; FFP, plasma fresco congelado. *Se dispuso de información sobre el momento de inicio en 88 pacientes (se conocía el momento de inicio del 76% de los casos de hemorragia intracraneal intraparenquimatosa asociada a anticoagulantes, mientras que esta información solo estaba disponible en el 54% del total combinado de otras HICaa). †16 valores no disponibles. Métodos El Canadian PCC Registry En 2008, Health Canada obtuvo la autorización para su primer producto de PCC, Octaplex, para la corrección urgente de la INR en pacientes tratados con warfarina. Los centros regionales de asistencia terciaria de Canadá especializados en ictus adoptaron protocolos institucionales de infusión de Octaplex para los pacientes con HIC en el contexto de una elevación de la INR y un uso conocido de warfarina. En noviembre de 2008, pusimos en marcha el Canadian PCC Registry (CanPro) consistente en un registro prospectivo de pacientes hospitalizados en el que se incluía a todos los pacientes consecutivos tratados con Octaplex en 3 centros de ictus de nivel terciario (Calgary, Alberta; Edmonton, Alberta; y Ottawa, Ontario). En el momento del diagnóstico de una HICaa, los pacientes que acudían a estos 3 centros participantes recibieron Octaplex; el banco de sangre incluía al paciente en el registro una vez preparado y administrado el tratamiento de Octaplex. Posteriormente obtuvimos los datos clínicos, de técnicas de imagen y de laboratorio a partir de las historias clínicas de los pacientes incluidos en el registro. El estudio fue aprobado por los comités éticos de investigación humana de los 3 centros participantes y se siguieron los procedimientos establecidos según las guías de los centros. Variables de valoración y definiciones Las variables de valoración primarias fueron la corrección de la INR, los episodios trombóticos y la mortalidad intrahospitalaria. La corrección rápida de la INR se definió como la obtención de una INR < 1,5 en el plazo de 1 hora tras la infusión de PCC. Los acontecimientos adversos incluyeron todos los episodios trombóticos diagnosticados por los clínicos responsables del tratamiento en un plazo de 30 días tras la infusión de PCC. Las variables de valoración secundarias incluyeron la expansión significativa del hematoma, definida como un crecimiento ≥ 6 mL o de un 33%7-9 y la evolución clínica en el momento del alta. Se revisó la totalidad de la historia clínica hospitalaria de los pacientes para identificar posibles acontecimientos adversos. Analizamos los volúmenes del hematoma parenquimatoso con el empleo de planimetría computarizada10,11 que llevaron a cabo evaluadores que no conocían la forma de presentación ni la evolución clínica de los pacientes. Evaluamos los resultados clínicos con el empleo de la escala de Rankin modificada; las PCC indica concentrado de complejo de protrombina; TVP, trombosis venosa profunda; IM, infarto de miocardio; EP, embolia pulmonar. puntuaciones se basaron en las revisiones de las historias clínicas12 realizadas por investigadores que disponían de una certificación de capacitación en el uso de la escala de Rankin modificada. Basándonos en lo indicado por estudios anteriores y por ensayos actualmente en curso, definimos la mala evolución clínica como una puntuación de 4 a 6 en la escala de Rankin modificada7-9,13. Análisis estadístico Limitamos el análisis multivariado de los factores predictivos de una mala evolución clínica y de la mortalidad a los pacientes con hemorragia intraparenquimatosa. Utilizamos un análisis univariado para estudiar las posibles asociaciones entre los resultados clínicos y las variables de edad, sexo, antecedentes patológicos, medicaciones antitrombóticas, presión arterial basal, escala del coma de Glasgow (GCS), glucosa, hemoglobina, INR, volumen del hematoma, extensión intraventricular, dosis de Octaplex, tiempo desde el inicio hasta el tratamiento, uso de plasma fresco congelado, corrección rápida de la INR y retirada del tratamiento. Aplicamos la prueba exacta de Fisher para las comparaciones de las variables dicotómicas o discretas y la prueba de t o la prueba de suma de rangos de Wilcoxon para las de las variables continuas. A continuación elaboramos modelos de regresión logística multivariada con el empleo de las variables candidatas asociadas a la variable de valoración primaria (p ≤ 0,15) en el análisis univariado; se eliminaron las variables no significativas (p > 0,05) mediante un sistema escalonado retrógrado, con objeto de establecer un modelo mínimo con OR ajustadas. Utilizamos el programa IBM SPSS 18.0 for Mac (Somers, NY, EEUU) para todos los análisis estadísticos. Resultados Entre noviembre de 2008 y octubre de 2010, un total de 141 pacientes consecutivos recibieron Octaplex para la HICaa. La mediana de edad fue de 78 años (rango intercuartiles, 14); un 59,6% eran varones. Un total de 66 (46,8%) pacientes presentaron un hematoma intraparenquimatoso (HIP), 59 (41,8%) un hematoma subdural sin Tabla 4. Volúmenes de hematoma intraparenquimatoso basal y en el seguimiento Número Mediana (RIC) Volumen basal de HIP, mL 68 15,8 (31,8) Volumen de HIP en el seguimiento, mL 33 16,8 (36) Crecimiento del HIP >33% o >6 mL (%) 15/33 Tiempo hasta la TC de seguimiento 19 45,5% 22 hr 41 min (13,75 hr) RIC indica rango intercuartiles; HIP, hematoma intraparenquimatoso. 102 Stroke Noviembre 2012 Figura. Crecimiento significativo del hematoma a pesar de la corrección de la INR con PCC. El paciente fue tratado con 1.000 U de PCC y 10 mg de vitamina K 98 minutos después de la TC basal. El nuevo valor de INR fue de 1,3 a los 42 minutos del tratamiento con PCC y de 1,2 al día siguiente. INR indica ratio normalizada internacional; PCC, concentrado de complejo de protrombina. componente parenquimatoso, 15 (10,6%) una hemorragia subaracnoidea, y 1 (0,7%) un hematoma epidural aislado (Tabla 1). La mediana de la INR en el momento de la presentación inicial fue de 2,6 (rango intercuartiles, 2,0). La indicación más frecuente para el uso de warfarina fue la fibrilación auricular (75%). Tratamiento con Octaplex e INR Los pacientes fueron tratados con una mediana de dosis de Octaplex de 1.000 UI (rango intercuartiles, 500; basado en la equivalencia de Factor IX); un 85,6% de los pacientes recibieron vitamina K, y un 22,4% recibieron también plasma fresco congelado (Tabla 2). La mediana de tiempo transcurrido desde el inicio hasta el tratamiento fue de 380 minutos. La INR postratamiento se obtuvo en el plazo de 1 hora en 78 de los 141 (55,3%) pacientes y en el plazo de 6 horas en 124 de 141 (87,9%) pacientes. Se alcanzó una corrección de la INR hasta un valor < 1,5 en el 71,8% al cabo de 1 hora y en el 76,4% a las 6 horas. En los pacientes con una HICaa intraparenquimatosa, la INR postratamiento se obtuvo en el plazo de 1 hora en 39 de 71 (54,9%) casos; se alcanzó una corrección de la INR hasta un valor < 1,5 en 28 de 39 (71,8%). Complicaciones trombóticas Los episodios trombóticos asociados al uso de Octaplex son los que se indican en la Tabla 3. Aunque la tasa total de epiTabla 5. Resultados clínicos según la clasificación de la HICaa Tipo de hemorragia intracraneal Número Mortalidad intrahospitalaria* mRS al alta (mediana [RIC])† Intraparenquimatosa Subdural 71 30 (42,3%) 5 [3]‡ 61 21 (34,4%) 3 [4]§ Epidural 1 0 3 Subaracnoidea 8 1 (12,5%) 3 [3] HICaa indica hemorragia intracraneal asociada a anticoagulantes; mRS, escala de Rankin modificada; RIC, rango intercuartiles. *p = 0,3. †p = 0,012. ‡mRS no disponible en 9. §mRS no disponible en 2. sodios trombóticos a 30 días fue del 5%, solamente se produjeron 3 episodios en un plazo de 7 días de tratamiento (2%). Pacientes con HIP De 71 pacientes con HIP, en 33 (46,5%) se dispuso de una TC de seguimiento. De ellos, 15 (45,5%) presentaron una expansión del hematoma hasta un volumen > 6 mL o un aumento del volumen de un 33% (Tabla 4; Figura). Las tasas de mortalidad y la mala evolución clínica fueron máximas en el grupo de HIP (Tabla 5). El análisis univariado exploratorio puso de manifiesto que los pacientes con una expansión del hematoma > 6 mL o 33% tenían unas tasas de mortalidad significativamente superiores a las de los pacientes sin esta característica (66,7% frente a 22,2%; p = 0,015). En los pacientes con HIP, el análisis univariado reveló la existencia de asociaciones entre la mortalidad y la GCS baja (Z = –3,4, p = 0,001), el mayor volumen basal del hematoma parenquimatoso (t = 1,61, p = 0,112), el volumen basal total del hematoma (ventricular + parenquimatoso; t = –2,64, p < 0,010), un menor intervalo de tiempo entre inicio y tratamiento (t = 2,46, p = 0,017) y la paliación (p < 0,001). De igual modo, los análisis exploratorios pusieron de relieve la existencia de asociaciones entre el mal resultado funcional y la GCS baja (Z = –3,09, p = 0,002), el volumen total del hematoma (t = –1,607, p = 0,113), los antecedentes de insuficiencia cardiaca congestiva (p = 0,06), los intervalos de tiempo entre inicio y tratamiento menores (t = 2,96, p = 0,005) y la paliación (p < 0,001). Dado que el volumen total del hematoma y el volumen del hematoma parenquimatoso son colineales, se utilizó el volumen total para los modelos multivariables ya que su asociación con la mortalidad era más robusta. Tras un análisis de regresión multivariado, tan solo la GCS baja (OR ajustada, 0,79 por punto; IC del 95%, 0,64-0,98; p = 0,032) y la paliación (OR ajustada, 43,01; IC del 95%, 4,87-379,71; p = 0,001) presentaron una asociación independiente con la mortalidad. La GCS baja se asoció también a la mala evolución clínica (OR ajustada, 0,678 por punto; IC del 95%, 0,50-0,91; p = 0,009). Todos los pacientes a los que se aplicó paliación presentaron una mala evolución clínica; en consecuencia, esta variable fue excluida del modelo. Dowlatshahi y cols. Mal pronóstico de la hemorragia intracraneal asociada a warfarina 103 Discusión En un registro prospectivo multicéntrico de pacientes con HICaa, observamos que el tratamiento con PCC revertía la anticoagulación en el 71,8% de los pacientes en el plazo de 1 hora tras el tratamiento. Esto se asoció a una tasa de episodios trombóticos del 2% a lo largo de 7 días. No obstante, las tasas de mortalidad se mantuvieron altas y los resultados clínicos fueron en general malos a pesar de la corrección de la coagulopatía. En la mayoría de los pacientes se repitió la determinación de la INR en las 6 primeras horas tras el tratamiento; en un 23,6% no se alcanzó el objetivo de una INR < 1,5 en ese momento, lo cual puede reflejar el uso de una dosis inferior de PCC durante el periodo de estudio. Es posible que esto haya contribuido luego a producir la elevada tasa de mala evolución clínica. La mediana de dosis utilizada en nuestro estudio fue de 1.000 U y se basó en una recomendación realizada en 2008 por el National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products que aconsejaba iniciar el tratamiento con esa dosis y complementarla luego si la corrección era insuficiente 15 minutos después de la infusión14. Esto es inferior a la recomendación del fabricante, que se basa en el peso y la INR (empezando con 1.000 U para un paciente de 70 kg a una INR 2,0, y con una dosis máxima de 3.000 U). El National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products ha modificado y elevado luego sus recomendaciones de dosis, para pasar a utilizar un método basado en la INR tras una revisión realizada en 2010 (1.000 U para una INR <3,0, 2.000 U para una INR 3–5, y 3.000 U para una INR >5)15. Hubo un total de 7 episodios trombóticos en los 30 días siguientes al tratamiento con PCC. Se produjeron tres ictus isquémicos, que podían haber estado relacionados con la fibrilación auricular subyacente no tratada, uno fue una extensión de una trombosis venosa profunda previa, y uno fue un infarto de miocardio en el contexto de una embolia pulmonar no tratada. Aunque no podemos descartar por completo una relación causal entre el tratamiento con PCC y los episodios trombóticos, la tasa de acontecimientos adversos fue relativamente baja y ello podría estar relacionado con la indicación inicial para la anticoagulación. Nuestra baja tasa de acontecimientos adversos es similar a la de los 2 estudios anteriores en los que se ha utilizado la misma formulación de PCC16,17, aunque reconocemos que puede haber habido episodios trombóticos subclínicos que pasaran desapercibidos al no haber aplicado un protocolo de detección sistemática18. Observamos una tasa de mortalidad del 42,3% en los pacientes con una HICaa intraparenquimatosa después del tratamiento con PCC, cifra esta que es inferior a las del 62% y 67% presentadas en 2 estudios recientes de la HICaa2,6 y está más próxima a las tasas de mortalidad asociadas a la HIC no coagulopática19-21. Aunque las comparaciones indirectas no son válidas, estos datos concuerdan con la hipótesis de que la corrección de la INR modifica los resultados esperados tras una HICaa aproximándolos a los de una HIC no coagulopática, que no obstante son clínicamente devastadores. Observamos también un peor resultado clínico en los pacientes con HIP en comparación con los pacientes con otros tipos de hemorragias, aunque las diferencias de mortalidad carecían de significación estadística. Esto puede reflejar la existencia de diferencias en el tratamiento quirúrgico o médico secundario entre los distintos tipos de hemorragias y requerirá un examen más detallado. Sorprendentemente, no observamos que un menor intervalo de tiempo entre inicio y tratamiento tuviera un efecto positivo sobre los resultados clínicos. Es posible que esto se deba a que no se dispuso de datos sobre el momento de inicio en el 24% de los pacientes con HICaa intraparenquimatosa, pero es más probable que esté relacionado con una interacción con la gravedad de los déficits neurológicos, que constituyó un predictor robusto de la mortalidad y de la mala evolución clínica. El análisis univariado sugirió la existencia de una relación entre el menor intervalo de tiempo entre inicio y tratamiento y la mala evolución clínica, que dejaba de ser significativa al añadir al modelo la GCS. Nosotros proponemos que el proceso de asistencia se acelera cuando pacientes con síntomas graves y una GCS baja reciben una asistencia de urgencia, con lo cual el tiempo hasta el tratamiento se reduce, pero paradójicamente los resultados clínicos empeoran. Globalmente, el intervalo de tiempo entre la TC y el tratamiento en nuestro estudio fue superior al ideal y es preciso aplicar medidas para revertir con rapidez la coagulopatía en estos pacientes. Este es un posible mecanismo que puede explicar los resultados clínicos globales relativamente desfavorables observados en este estudio. Dada la baja tasa trombótica observada, autorizar el acceso directo a PCC en el servicio de urgencias para los médicos que tratan a estos pacientes es una medida que puede reducir el intervalo de tiempo hasta el tratamiento. De igual modo, el volumen basal del hematoma no se asoció a los resultados clínicos tras la introducción de un ajuste de covariables, lo cual difiere de lo indicado por un reciente estudio de la HICaa que sugiere que el volumen predice la mortalidad temprana (7 días) y el mal resultado funcional22. Parte de la discrepancia puede estar relacionada con las técnicas de medición del volumen; este último estudio utilizó la técnica ABC/2, que se sabe que infravalora o sobrevalora los hematomas grandes, irregulares o asociados al uso de anticoagulantes23-25, mientras que nosotros empleamos una planimetría asistida por ordenador específicamente desarrollada y validada para la medición de la HIC10. Sin embargo, una explicación más probable es que la potencia estadística de nuestro estudio fuera limitada a causa del tamaño muestral relativamente bajo de pacientes con volúmenes de HIP en nuestro estudio; la asociación con la mortalidad detectada en el análisis univariado quedó ocultada probablemente por el efecto robusto de la paliación y la GCS. Es interesante señalar que un reciente estudio sobre las limitaciones de la asistencia precoz tras la HIC observó también que la asociación entre el volumen del hematoma y la mortalidad quedaba notablemente atenuada al incluir en el modelo la retirada de la asistencia (OR ajustada para el volumen, 1,01)26. Nuestro estudio tiene varias limitaciones; fue un estudio observacional y no dispuso de exploraciones de TC de seguimiento estandarizadas, lo cual impidió realizar una evaluación exacta de la expansión del hematoma en la mayoría de los pacientes. En consecuencia, existe la posibilidad de un sesgo de indicación en los pacientes con TC de seguimiento; las exploraciones de imagen podrían haberse solicitado en respuesta a un agravamiento neurológico o a la sospecha de una recidiva hemorrágica. 104 Stroke Noviembre 2012 Además, la variabilidad en cuanto al momento de obtención de la INR de seguimiento complicó la evaluación temporal de la corrección de la INR. Tampoco pudimos evaluar la etiología de la hemorragia en nuestra cohorte, ni su posible interacción con la corrección de la INR y con el resultado clínico. Por último, las puntuaciones en la escala de Rankin modificada al alta se obtuvieron a partir de las historias clínicas, de manera similar a lo hecho en anteriores estudios observacionales27,28. No obstante, nuestro estudio tiene la ventaja de la inclusión consecutiva de 3 centros terciarios independientes especializados en ictus, y es uno de los estudios más amplios de la HICaa realizados hasta la fecha. Además, tuvimos en cuenta los efectos de la retirada de la asistencia, que se sabe que introducen una confusión en los resultados de la HIC26,29-30. En resumen, observamos que el tratamiento con PCC corregía rápidamente la INR en la mayoría de los pacientes con HICaa, si bien las tasas de mortalidad y morbilidad se mantenían elevadas. Estos resultados sugieren que la evolución clínica tras una HICaa puede ser devastadora incluso con una estrategia de reversión31 y resaltan la necesidad de estudios experimentales controlados para evaluar la reversión de la anticoagulación, como el ensayo multicéntrico, controlado y aleatorizado INR Normalization in Coumadin-Associated Intracerebral Haemorrhage, que se está realizando actualmente32. Fuentes de financiación El Dr Dowlatshahi cuenta con el apoyo de la JP Bickell Foundation y una Medicine Research Salary Award del University of Ottawa Department of Medicine. El Dr Butcher recibe subvenciones y apoyo salarial de Alberta Innovates Health Solutions, los Canadian Institutes for Health Research, y ocupa una Canada Research Chair. El Dr Coutts ha recibido apoyo salarial de Alberta-Innovates-Health Solutions y la beca de Distinguished Clinician Scientist de la Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada, financiada conjuntamente por los Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR), el Institute of Circulatory and Respiratory Health y AstraZeneca Canada Inc. M. Bernbaum ha recibido una beca de verano para estudiantes de la Canadian Stroke Network para este trabajo. Declaraciones El Dr. Dowlatshahi ha recibido honorarios por conferencias de Boehringer Ingelheim y Octapharma y ha formado parte de un consejo asesor de Bayer Canadá. El Dr. Butcher ha recibido honorarios por conferencias de Octapharma y ha formado parte de consejos asesores de Bayer Canadá, Boehringer Ingelheim y Pfizer/BMS. El Dr. Poon ha formado parte de consejos asesores de Pfizer, Octapharma y Novo Nordisk. El Dr. Giulivi ha formado parte de un consejo asesor de CSL Behring y Octapharma. El Dr. Nahirniak ha sido presidente del Prothrombin Complex Working Group del National Advisory Committee of Blood and Blood Products. El Dr. Coutts ha formado parte de un consejo asesor de Pfizer/BMS. Bibliografía References 1. Flaherty ML, Tao H, Haverbusch M, Sekar P, Kleindorfer D, Kissela B, et al. Warfarin use leads to larger intracerebral hematomas. Neurology. 2008;71:1084 –1089. 2. Cucchiara B, Messe S, Sansing L, Kasner S, Lyden P, for the CHANT Investigators. Hematoma growth in oral anticoagulant related intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2008;39:2993–2996. 3. Morgenstern LB, Hemphill JC, Anderson C, Becker K, Broderick JP, Connolly ES, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2010; 41:2108 –2129. 4. Kalina M, Tinkoff G, Gbadebo A, Veneri P, Fulda G. A protocol for the rapid normalization of INR in trauma patients with intracranial hemorrhage on prescribed warfarin therapy. Am Surg. 2008;74:858 – 861. 5. Huttner HB, Schellinger PD, Hartmann M, Köhrmann M, Juettler E, 2008;71:1084 –1089. 2. Cucchiara B, Messe S, Sansing L, Kasner S, Lyden P, for the CHANT Investigators. Hematoma growth in oral anticoagulant related intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2008;39:2993–2996. 3. Morgenstern LB, Hemphill JC, Anderson C, Becker K, Broderick JP, Connolly ES, et al. Guidelines for the management of spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2010; 41:2108 –2129. 4. Kalina M, Tinkoff G, Gbadebo A, Veneri P, Fulda G. A protocol for the rapid normalization of INR in trauma patients with intracranial hemorrhage on prescribed warfarin therapy. Am Surg. 2008;74:858 – 861. 5. Huttner HB, Schellinger PD, Hartmann M, Köhrmann M, Juettler E, Wikner J, et al. Hematoma growth and outcome in treated neurocritical care patients with intracerebral hemorrhage related to oral anticoagulant therapy: comparison of acute treatment strategies using vitamin K, fresh frozen plasma, and prothrombin complex concentrates. Stroke. 2006;37: 1465–1470. 6. Flaherty ML, Adeoye O, Sekar P, Haverbusch M, Moomaw CJ, Tao H, et al. The challenge of designing a treatment trial for warfarin-associated intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2009;40:1738 –1742. 7. STOP-IT Investigators. The spot sign for predicting and treating ICH growth study (STOP-IT). clinicaltrials.gov NCT00810888. Available at: http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00810888. Accessed November 2011. 8. Dowlatshahi D, Demchuk AM, Flaherty ML, Ali M, Lyden PL, Smith EE, on behalf of the VISTA Collaboration. Defining hematoma expansion in intracerebral hemorrhage: relationship with patient outcomes. Neurology. 2011;76:1238 –1244. 9. Demchuk AM, Dowlatshahi D, Rodriguez-Luna D, Molina CA, Silva Blas Y, Dzialowski I, et al. Prediction of haematoma growth and outcome in patients with intracerebral haemorrhage using the CT-angiography spot sign (PREDICT): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2012; 11:307–314. 10. Kosior JC, Idris S, Dowlatshahi D, Alzawahmah M, Eesa M, Sharma P, et al. Quantomo: validation of a computer-assisted methodology for the volumetric analysis of intracerebral haemorrhage. Int J Stroke. 2011;6: 302–305. 11. Zimmerman RD, Maldjian JA, Brun NC, Horvath B, Skolnick BE. Radiologic estimation of hematoma volume in intracerebral hemorrhage trial by CT scan. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2006;27:666 – 670. 12. Hylek EM, Go AS, Chang Y, Jensvold NG, Henault LE, Selby JV, et al. Effect of intensity of oral anticoagulation on stroke severity and mortality in atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1019 –1026. 13. Dowlatshahi D, Smith EE, Flaherty ML, Ali M, Lyden P, Demchuk AM, VISTA Collaborators. Small intracerebral haemorrhages are associated with less haematoma expansion and better outcomes. Int J Stroke. 2011; 6:201–206. 14. National Advisory Committee on Blood and Blood Products. Recommendations for use of Octaplex in Canada. 2008. Available at: www.transfusion medicine.ca/news/publications/octaplex%C2%AE-recommendations-nac. Accessed March 12, 2012. 15. National Advisory committee on Blood and Blood Products. Recommendations for use of prothrombin complex concentrates in Canada. 2011. Available at: www.nacblood.ca/resources/guidelines/PCC.html. Accessed March 12, 2012. 16. Riess HB, Meier-Hellmann A, Motsch J, Elias M, Kursten FW, Dempfle CE. Prothrombin complex concentrate (Octaplex) in patients requiring immediate reversal of oral anticoagulation. Thromb Res. 2007;121:9 –16. 17. Lubetsky A, Hoffman R, Zimlichman R, Eldor A, Zvi J, Kostenko V, et al. Efficacy and safety of a prothrombin complex concentrate (Octaplex) for rapid reversal of oral anticoagulation. Thromb Res. 2004;113: 371–378. 18. Diringer MN, Skolnick BE, Mayer SA, Steiner T, Davis SM, Brun NC, et al. Thromboembolic events with recombinant activated factor VII in spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage: results from the Factor Seven for Acute Hemorrhagic Stroke (FAST) trial. Stroke. 2010;41:48 –53. 19. van Asch CJ, Luitse MJ, Rinkel GJ, van der Tweel I, Algra A, Klijn CJ. Incidence, case fatality, and functional outcome of intracerebral haemorrhage over time, according to age, sex, and ethnic origin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:167–176. 20. Hemphill JC, Bonovich DC, Besmertis L, Manley GT, Johnston SC. The ICH score: a simple, reliable grading scale for intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2001;32:891– 897. 21. Broderick JP, Brott TG, Duldner JE, Tomsick T, Huster G. Volume of intracerebral hemorrhage. A powerful and easy-to-use predictor of 30-day mortality. Stroke. 1993;24:987–993. 22. Zubkov AY, Mandrekar JN, Claassen DO, Manno EM, Wijdicks EF, Rabinstein AA. Predictors of outcome in warfarin-related intracerebral hemorrhage. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:1320 –1325. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. 32. 27. O’Donnell M, Oczkowski W, Fang J, Kearon C, Silva J, Bradley C, et al. Preadmission antithrombotic treatment and stroke severity in patients with atrial fibrillation and acute ischaemic stroke: an observational study. Dowlatshahi y cols. Mal pronóstico de laLancet hemorragia intracraneal asociada a warfarina 105 Neurol. 2006;5:749 –754. 28. Dowlatshahi D, Demchuk AM, Fang J, Kapral M, Sharma M, Smith EE. Association of statins and statin discontinuation with poor outcome and survival following intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. Divani AA, Majidi S, Luo X, Souslian FG, Zhang J, Abosch A, et al. The 2012;43:xxx–xxx. ABCs of accurate volumetric measurement of cerebral hematoma. Stroke. 29. Becker KJ, Baxter AB, Cohen WA, Bybee HM, Tirschwell DL, Newell 2011;42:1569 –1574. DW, et al. Withdrawal of support in intracerebral hemorrhage may lead Wang CW, Juan CJ, Liu YJ, Hsu HH, Liu HS, Chen CY, et al. Volumeto self-fulfilling prophecies. Neurology. 2001;56:766 –772. Dependent overestimation of spontaneous intracerebral hematoma 30. Zahuranec DB, Morgenstern LB, Sánchez BN, Resnicow K, White DB, volume by the ABC/2 formula. Acta Radiol. 2009;50:306 –311. Hemphill JC. Do-not-resuscitate orders and predictive models after intraFreeman WD, Barrett KM, Bestic JM, Meschia JF, Broderick DF, Brott cerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2010;75:626 – 633. TG. Computer-assisted volumetric analysis compared with ABC/2 31. Rizos T, Rohde S, Dörner N, Steiner T. Ongoing intracerebral bleeding method for assessing warfarin-related intracranial hemorrhage volumes. despite hemostatic treatment associated with a spot sign in a patient on Neurocrit Care. 2008;9:307–312. oral anticoagulation therapy. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28:623– 624. Zahuranec DB, Brown DL, Lisabeth LD, Gonzales NR, Longwell PJ, 32. Steiner T, Freiberger A, Griebe M, Hüsing J, Ivandic B, Kollmar R, et al. Smith MA, et al. Early care limitations independently predict mortality International normalised ratio normalisation in patients with coumarinafter intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2007;68:1651–1657. related intracranial haemorrhages—the INCH trial: a randomised conO’Donnell M, Oczkowski W, Fang J, Kearon C, Silva J, Bradley C, et al. trolled multicentre trial to compare safety and preliminary efficacy of Preadmission antithrombotic treatment and stroke severity in patients fresh frozen plasma and prothrombin complex—study design and with atrial fibrillation and acute ischaemic stroke: an observational study. protocol. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:271–277. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:749 –754. Dowlatshahi D, Demchuk AM, Fang J, Kapral M, Sharma M, Smith EE. Association of statins and statin discontinuation with poor outcome and survival following intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2012;43:xxx–xxx. Becker KJ, Baxter AB, Cohen WA, Bybee HM, Tirschwell DL, Newell DW, et al. Withdrawal of support in intracerebral hemorrhage may lead to self-fulfilling prophecies. Neurology. 2001;56:766 –772. Zahuranec DB, Morgenstern LB, Sánchez BN, Resnicow K, White DB, Hemphill JC. Do-not-resuscitate orders and predictive models after intracerebral hemorrhage. Neurology. 2010;75:626 – 633. Rizos T, Rohde S, Dörner N, Steiner T. Ongoing intracerebral bleeding despite hemostatic treatment associated with a spot sign in a patient on oral anticoagulation therapy. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2009;28:623– 624. Steiner T, Freiberger A, Griebe M, Hüsing J, Ivandic B, Kollmar R, et al. International normalised ratio normalisation in patients with coumarinrelated intracranial haemorrhages—the INCH trial: a randomised controlled multicentre trial to compare safety and preliminary efficacy of fresh frozen plasma and prothrombin complex—study design and protocol. Int J Stroke. 2011;6:271–277. Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by Springer Healthcare on September 13, 2012 ournals.org/ by Springer Healthcare on September 13, 2012