Vertical Integration, Appropriable Rents, and the Competitive

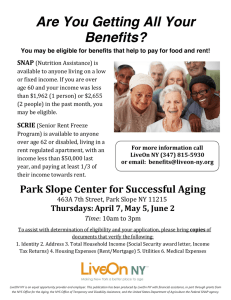

Anuncio