Prevalence of Early Dementia After First-Ever Stroke A 24

Anuncio

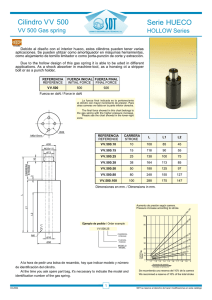

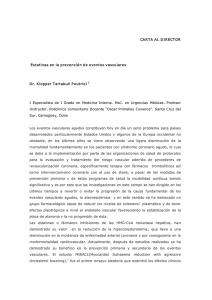

Prevalence of Early Dementia After First-Ever Stroke A 24-Year Population-Based Study Yannick Béjot, MD; Corine Aboa-Eboulé, MD; Jérôme Durier, MD; Olivier Rouaud, MD; Agnès Jacquin, MD; Eddy Ponavoy, MD; Dominique Richard, MD; Thibault Moreau, MD; Maurice Giroud, MD Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 19, 2016 Backgound and Purpose—No data about temporal change in the prevalence of poststroke dementia are available. We aimed to evaluate trends in the prevalence of early poststroke dementia. Methods—From 1985 to 2008, overall first-ever strokes occurring within the population of the city of Dijon, France (150 000 inhabitants) were recorded. The presence of dementia was diagnosed during the first month after stroke, according to Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third and Fourth Editions criteria. Time trends were analyzed according to 4 periods: 1985 to 1990, 1991 to 1996, 1997 to 2002, and 2003 to 2008. Logistic regression was used for nonmultivariate analyses. Results—Over the 24 years, 3948 first-ever strokes were recorded. Among patients with stroke, 3201 (81%) were testable of whom 653 (20.4%) had poststroke dementia (337 women and 316 men). The prevalence of nontestable (mostly due to death) patients declined from 28.0% to 10.2% (P⬍0.0001). Multivariate analysis revealed significant temporal changes in the prevalence of poststroke dementia; prevalence in the second and fourth periods was, respectively, almost half and twice that in the first period. The prevalence of poststroke dementia associated with lacunar stroke was 7 times higher than that in intracerebral hemorrhage but declined over time as did prestroke antihypertensive medication. Age, several vascular risk factors, hemiplegia, and prestroke antiplatelet agents were associated with an increased prevalence of poststroke dementia. Conclusions—This study covering a period of 24 years highlights temporal changes in the prevalence of early dementia after first-ever stroke. These changes may be explained by concomitant determinants of survival and incidence such as stroke care management or prestroke medication. (Stroke. 2011;42:607-612.) Key Words: dementia 䡲 epidemiology 䡲 risk factors 䡲 stroke B eyond its harmful effect on patients’ functional capabilities, stroke is also associated with a higher risk of cognitive impairment and dementia; a history of stroke almost doubles the risk of dementia in the population aged ⬎65 years.1 The prevalence of poststroke dementia was recently reviewed by Pendlebury and Rothwell.2 Despite a heterogeneous study design and case mix, the authors concluded that 7% to 23% of patients developed new dementia in the first year after their first-ever stroke. Data were obtained from both hospital- and population-based studies, but all of these studies were of short duration and included small numbers of patients. Hence, none provided reliable data on temporal changes in the prevalence of poststroke dementia. However, such information is essential to determine the impact of acute stroke care management on cognitive function and to provide projections for the burden of poststroke cognitive impairment to design appropriate health policy. Hence, the aim of this study was to evaluate trends in the prevalence of early poststroke dementia, from 1985 to 2008, from the Dijon Stroke Registry. Methods The prevalence of early dementia after stroke was studied in patients included from January 1, 1985, to December 31, 2008, in the Dijon Stroke Registry, Dijon, France. This registry complies with the core criteria defined by Sudlow and Warlow to approach the “ideal” stroke incidence study and provide reliable and comparable results.3,4 The study population comprised all residents of the city of Dijon (150 000 inhabitants). Data Collection Definition of Stroke Stroke was defined according to World Health Organization recommendations.5 The clinical diagnoses were validated on the basis of either CT or MRI.3 Only first-ever symptomatic stroke was considered for this study. The classification of the stroke subtype used since Received July 2, 2010; final revision received October 5, 2010; accepted October 26, 2010. From the Dijon Stroke Registry, EA4184 (Inserm and InVS; Y.B., C.A.-E., J.D., A.J., M.G.), IFR 100 (STIC-Santé), Faculty of Medicine, University of Burgundy and University Hospital of Dijon, France; and Centre Mémoire (Y.B., O.R., E.P., D.R., T.M., M.G.), Ressources et Recherche, Memory Clinic, University Hospital of Dijon, Dijon, France. Correspondence to Yannick Bejot, MD, Dijon Stroke Registry, Service de Neurologie, Hôpital Général, 3 Rue du Faubourg Raines, 21033 Dijon, France. E-mail ybejot@yahoo.fr © 2011 American Heart Association, Inc. Stroke is available at http://stroke.ahajournals.org DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595553 607 608 Stroke March 2011 Figure. Annual prevalence of poststroke dementia. Vertical bars represent 95% CI. Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 19, 2016 1985 was as follows: (1) lacunar infarct; (2) ischemic stroke from cardiac embolism; (3) nonlacunar noncardioembolic ischemic strokes; (4) spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage; and (5) subarachnoid hemorrhage.3 Case Ascertainment Information was provided by multiple overlapping sources3: (1) from the emergency rooms and all of the clinical and radiological departments of Dijon University Hospital with the diagnosis of stroke made by a neurologist; (2) from the 3 private hospitals of the city with diagnosis made by private neurologists; (3) from the patient’s home or from the nursing homes of the city with diagnosis assessed by the general practitioners with the help of an outpatient clinic with either a public or private neurologist; (4) from the 3 private radiological centers to identify missed cases; (5) from the Doppler ultrasound centers of the University Hospital and private centers; and (6) from the death certificates obtained from the local Social Security Bureau that is responsible for registering all deaths in the community to identify fatal strokes occurring in nonhospitalized patients. All of the collected death certificates were checked by a member of our team. Collection of Vascular Risk Factors Vascular risk factors were collected with the same methodology over the whole study period.3 We recorded hypertension if high blood pressure was noted in a patient’s medical history (either self-reported or from medical notes) or if a patient was under antihypertensive treatment. Diabetes mellitus was recorded if a glucose level of ⱖ7.8 mmol/L had been reported in the medical record or if the patient was under insulin or oral hypoglycemic agents. Hypercholesterolemia was considered if a total cholesterol level ⱖ5.7 mmol/L was reported in the medical history of the patient or if patients were treated with lipid-lowering therapy. We also recorded a history of atrial fibrillation, previous myocardial infarction, and a history of transient ischemic attack. Smoking was not included in the final analysis because of 15% of missing data. Assessment of Poststroke Dementia Given the design of our registry and its inherent constraints, the evaluation of cognitive function was performed by a neurologist in the early stages of the stroke, that is, within the first month after stroke onset to collect as much information as possible. Patients and their relatives attended an interview and the diagnosis of poststroke dementia was based on a simple standardized clinical approach using Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third and Fourth Editions.6,7 Therefore, the diagnosis of dementia was made if, according to the informant and the examination of the patient, multiple cognitive deficits manifested by memory impairment associated with ⱖ1 cognitive disturbances, including language disturbance, apraxia, agnosia, or disturbance in executive function, with significant impairment in social or occupational function representing a significant decline from a previous level of function were noted. Statistical Analysis The prevalence of poststroke dementia was calculated as the ratio of the number of patients with poststroke dementia to the total number of first-ever strokes in testable patients. A 95% CI was computed for all estimates. We plotted data per year to graphically assess trends in the prevalence of poststroke dementia over 24 years. Due to a multimodal variation of prevalence over the years (Figure), the time period was split into 4 intervals of 6 years: 1985 to 1990, 1991 to 1996, 1997 to 2002, and 2003 to 2008, with 1985 to 1990 as the reference. Baseline characteristics for analyses were demographics, vascular risk factors, prestroke treatments, and clinical features. Data on statins were analyzed by univariate analysis only because they had only been recorded in the registry since 2006. Proportions, ORs, and means of baseline characteristics were compared between patients with and without poststroke dementia using the 2 test, logistic regression, and analysis of variance, respectively. Univariate associations among age, sex, time periods, vascular risk factors, prestroke treatments, stroke subtypes, clinical features at onset, and poststroke dementia were analyzed using logistic regression to estimate unadjusted ORs. In multivariate analyses, we introduced into the models age, sex as well as all potential confounders with a probability value ⬍0.20 in univariate analysis. We investigated whether there were nonlinear trends over the study periods (unequal prevalence over study periods) for age, prestroke treatment, stroke subtypes, vascular risk factors, and clinical features as observed for the prevalence of poststroke dementia. A likelihood ratio test was performed to examine whether the fits of multivariate nested models were improved by including statistical interaction terms of study periods with baseline characteristics. None of the statistical interaction terms were significant except for lacunar subtype with study periods (P⬍0.0001) and the prior antihypertensive treatment with study periods (P⫽0.0061), which were taken into account along with the main effects in the final multivariate models. Probability values ⬍0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed with STATA 10.0 software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Ethics Our registry was approved by the National Ethics Committee and the French Institute for Public Health Surveillance. Béjot et al Results Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 19, 2016 Over the whole study period, 3948 patients with first-ever stroke were recorded (1842 in men, 2106 in women). Among patients with stroke, 3201 (81%) were testable and included in the analyses. The inability to test the cognitive status of patients (n⫽747 [19%]) was due to either severe aphasia (n⫽66 [8.7%]) or death (n⫽681 [91.3%]) in the acute phase of stroke. The prevalence of nontestable patients decreased with study periods from 28.0% in 1985 to 1990 to 24.7% in 1991 to 1996, 15.5% in 1997 to 2002, and 10.2% in 2003 to 2008 (P⬍0.0001). Nontestable patients were older (79.1⫾12.5 years) than testable patients (72.9⫾14.7; P⬍0.0001) with an increasing age over the 4 study periods (respectively, 77.4⫾11.7, 78.6⫾12.5, 81.1⫾12.5, and 81.3⫾13.0 years; P⫽0.004) contrary to testable patients (respectively, 72.0⫾14.6, 73.6⫾13.9, 72.8⫾14.9, and 73.0⫾15.0 years; P⫽0.261). They had a more severe initial presentation, more often prior transient ischemic attack, myocardial infarction, or anticoagulant therapy, but they had a lower prevalence of hypercholesterolemia and prior antiplatelet medication than did testable patients (P⬍0.05). Among testable patients, 653 (20.4%) had poststroke dementia (337 women and 316 men). The annual prevalence distribution of poststroke dementia roughly showed a trimodal curve with 3 peaks, in 1990 (25.6%), 1998 (21.8%), and 2003 (25.2%), with varying falls in prevalence in between (Figure). There was no significant temporal change (P⫽0.123) in the prevalence of poststroke dementia over the 4 study periods with, respectively, 23.7% (95% CI, 20.4% to 27%), 19.3% (16.4% to 22.3%), 19% (16.4% to 21.6%), and 20.2% (17.8% to 22.7%). Patients with poststroke dementia differed from those without poststroke dementia. They were older (77.3⫾10.8 years versus 71.7⫾15.4 years, P⫽0.0001); had a higher prevalence of several vascular risk factors, including hypertension, diabetes, atrial fibrillation, previous myocardial infarction, and history of transient ischemic attack; and were more likely to have received strokepreventive medications, including antiplatelet agents and antihypertensive treatment (Table 1). In addition, they were more likely to have hemiplegia at admission, and there was a higher prevalence of lacunar stroke but a lower prevalence of intracerebral hemorrhage, subarachnoid hemorrhage, and nonlacunar noncardioembolic ischemic strokes in these patients (Table 1). The prestroke use of anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents in the whole study population showed linear trends from, respectively, 2.8% and 5.8% in the first period to 9.2% and 25.7% in the last period (P⬍0.0001). However, the use of antihypertensive treatment showed a nonlinear trend with 48.1%, 53.4%, 51.0%, and 45.6% over the 4 periods (P⫽0.003). Multivariate analyses revealed a significant temporal change in the prevalence of poststroke dementia in the second (1991 to 1996) and fourth periods (2003 to 2008) as compared with the first period (1985 to 1990). The prevalence in the second period was almost half that in the first, whereas prevalence in the fourth period was twice that in the first. Prevalence in the third period was the same as that in the first (P⬍0.0001). Several variables remained significant in the multivariate model (Table 2). Age correlated strongly with Temporal Trends in Poststroke Dementia in Dijon 609 poststroke dementia with a relative 3% increase for each additional year of age. The prevalence of poststroke dementia in patients with lacunar stroke was 7 times that in patients with intracerebral hemorrhage. Stratum-specific analyses by periods revealed a significant temporal decrease in the prevalence of poststroke dementia among patients who had lacunar stroke compared with those who did not. Hypertension, previous myocardial infarction, hemiplegia at onset, and prestroke treatment by antiplatelet agents were all associated with an increased prevalence of poststroke dementia. In contrast, the prevalence of poststroke dementia in patients with hypercholesterolemia was 24% lower than that in patients without hypercholesterolemia. Overall, antihypertensive treatment was not associated with poststroke dementia. However, stratum-specific analyses by periods revealed a significant temporal decrease in the risk of poststroke dementia over the last 2 periods (1997 to 2002 and 2003 to 2008) among patients who had been treated with prior antihypertensive medication compared with those who had not. Discussion This is the first study to evaluate temporal trends of early dementia after stroke over 24 years with constant methodologies for stroke ascertainment and the same definition of dementia throughout the study period. The prevalence of poststroke dementia observed in this study is similar to that reported in hospital-based studies, including first-ever stroke and prestroke dementia. In their meta-analysis, Pendlebury and Rothwell estimated the general prevalence from such studies at 26.5% (95% CI, 24.3% to 28.7%) irrespective of the delay after stroke onset.2 In contrast, the only population-based study that included firstever stroke and did not exclude prestroke dementia found a lower prevalence of 12.5% (95% CI, 5.6% to 19.4%).8 However, some differences in the methodology applied may account for these discrepancies between the results of this study and ours. In the latter study, cognitive assessment was performed at 1 year, and the patients with stroke were younger than ours. Several other studies have evaluated the prevalence of dementia in the first 3 months after stroke onset. They reported a frequency ranging from 18.7% to 21.2%, which is in line with our results despite their hospitalbased setting.9 –13 Although it seemed to be stable over time, multivariate analysis demonstrated that the prevalence of poststroke dementia changed in the second (1991 to 1996) and fourth (2003 to 2008) periods. Indeed, it was, respectively, half and twice the prevalence of the first period. We investigated whether these trends could also be observed for age, prestroke treatment, stroke subtypes, vascular risk factors, and clinical features. There was no temporal change for age in testable patients, but there was an increasing age over the study periods for nontestable patients. In addition, lacunar stroke and antihypertensive treatment were both associated with a significant temporal decline in the prevalence of poststroke dementia. Theoretical explanations for these results may be changes in the prevalence of prestroke dementia, in the incidence of poststroke dementia, and/or in survival after stroke. The decline in the prevalence of poststroke dementia 610 Stroke Table 1. March 2011 Characteristics of Patients With and Without Poststroke Dementia No Poststroke Cognitive Disorder (N⫽2548) Poststroke Cognitive Disorder Vs No Poststroke Cognitive Disorder Poststroke Cognitive Disorder (N⫽653) No. % 95% CI No. % 95% CI OR 95% CI P ⬍40 119 4.7% 3.9% 5.5% 3 0.5% 0.0% 1.0% 0.09 0.03 0.29 ⬍0.001 40–50 147 5.8% 4.9% 6.7% 9 1.4% 0.5% 2.3% 0.22 0.11 0.44 ⬍0.001 50–60 234 9.2% 8.1% 10.3% 29 4.4% 2.9% 6.0% 0.45 0.30 0.67 ⬍0.001 60–70 424 16.6% 15.2% 18.1% 91 13.9% 11.3% 16.6% 0.79 0.62 1.01 0.064 70–80 751 29.5% 27.7% 31.2% 218 33.4% 29.8% 37.0% 1.21 1.01 1.45 0.038 ⬎80 873 34.3% 32.4% 36.1% 303 46.4% 42.6% 50.2% 1.66 1.40 1.98 ⬍0.001 Male sex 1188 46.6% 44.7% 48.6% 316 48.4% 44.5% 52.2% 1.08 0.91 1.28 0.37 Age, years Stroke subtype Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 19, 2016 Intracerebral hemorrhage 238 9.3% 8.2% 10.5% 28 4.3% 2.7% 5.8% 0.47 0.32 0.70 ⬍0.001 Subarachnoid hemorrhage 85 3.3% 2.6% 4.0% 3 0.5% 0.0% 1.0% 0.13 0.04 0.42 0.001 Lacunar 554 21.7% 20.1% 23.3% 333 51.0% 47.2% 54.8% 3.57 2.99 4.27 ⬍0.001 Cardioembolic 394 15.5% 14.1% 16.9% 96 14.7% 12.0% 17.4% 1.01 0.80 1.28 0.94 1210 47.5% 45.5% 49.4% 184 28.2% 24.7% 31.6% 0.43 0.36 0.52 ⬍0.001 67 2.6% 2.0% 3.3% 9 1.4% 0.5% 2.3% 0.57 0.29 1.11 0.10 Ischemic stroke Nonlacunar noncardioembolic Undetermined Vascular risk factors 1624 63.7% 61.9% 65.6% 483 74.0% 70.6% 77.3% 1.58 1.31 1.91 ⬍0.001 Diabetes 358 14.1% 12.7% 15.4% 114 17.5% 14.5% 20.4% 1.30 1.04 1.63 0.024 hypercholesterolemia 631 24.8% 23.1% 26.4% 139 21.3% 18.1% 24.4% 0.82 0.67 1.01 0.064 Atrial fibrillation 445 17.5% 16.0% 18.9% 147 22.5% 19.3% 25.7% 1.42 1.15 1.75 0.001 Myocardial infarction 403 15.8% 14.4% 17.2% 153 23.4% 20.2% 26.7% 1.61 1.30 1.98 ⬍0.001 TIA 280 11.0% 9.8% 12.2% 104 15.9% 13.1% 18.7% 1.50 1.17 1.91 0.001 Hypertension Prestroke treatments Anticoagulants 158 6.2% 5.3% 7.1% 33 5.1% 3.4% 6.7% 0.79 0.54 1.16 0.24 Antiplatelet agents 501 19.7% 18.1% 21.2% 175 26.8% 23.4% 30.2% 1.52 1.25 1.85 ⬍0.001 1225 48.1% 46.1% 50.0% 356 54.5% 50.7% 58.3% 1.26 1.07 1.50 0.007 46 10.6% 7.7% 13.6% 5 5.4% 0.7% 10.2% 0.48 0.19 1.25 0.13 Antihypertensive treatment Statins (2006–2008) Clinical features at onset Coma 101 4.0% 3.2% 4.7% 26 4.0% 2.5% 5.5% 1.07 0.70 1.64 0.77 Hemiplegia 1806 70.9% 69.1% 72.6% 522 79.9% 76.9% 83.0% 1.63 1.32 2.01 ⬍0.001 Confusion 259 10.2% 9.0% 11.3% 79 12.1% 9.6% 14.6% 1.19 0.91 1.55 0.21 1103 43.3% 41.4% 45.2% 290 44.4% 40.6% 48.2% 1.03 0.87 1.22 0.74 Left hemisphere lesion TIA indicates transient ischemic attack. in the second period (1991 to 1996), as compared with the first period (1985 to 1990), may be explained by the fact that this period could have been a transition period. As observed in the first period, the prevalence of nontestable patients, mainly because of early death, was still high (25%), which consequently decreased the number of prevalent cases that would potentially have had poststroke dementia if they had survived, all the more so because these patients were older, had a more severe clinical presentation, and more vascular risk factors, so were at a high risk of dementia. In parallel, the frequency of prestroke preventive treatments, which are known to decrease the risk of dementia,14,15 showed a marked increase during this second period and may have contributed to the decrease in both the prevalence of prestroke dementia and the incidence of poststroke dementia. As a consequence, both the low number of prevalent cases and the lower incidence of poststroke dementia may have resulted in a significantly lower prevalence of poststroke dementia. Conversely, the third (1997 to 2002) and the fourth (2003 to 2008) periods were associated with a lower prevalence of nontestable patients due to a decrease in early case-fatality possible because of better acute stroke management. The consequence may have been a higher number of prevalent cases with poststroke dementia. Moreover, unlike the use of anticoagulants and antiplatelet agents, the use of prestroke hypertensive treatment did not show a linear trend but a decrease during the last 2 periods, which may have contributed to the increase in the prevalence of poststroke dementia. Béjot et al Temporal Trends in Poststroke Dementia in Dijon Table 2. Multivariate Analysis of Predictors of Poststroke Dementia OR 95% CI P Time period 1985–1990 1.00 1991–1996 0.52 0.30 0.90 0.018 1997–2002 1.14 0.72 1.81 0.576 2003–2008 1.91 1.25 2.91 0.003 Time period (continuous) 1.03 1.01 1.06 0.003 Age (continuous) 1.03 1.02 1.04 ⬍0.001 Stroke subtype Intracerebral hemorrhage 1.00 Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 19, 2016 Subarachnoid hemorrhage 0.47 0.14 1.60 0.225 Lacunar stroke 7.24 4.13 12.69 0.000 Lacunar stroke (period 1991–1996) 10.01 3.16 31.75 0.000 Lacunar stroke (period 1997–2002) 5.86 1.92 17.86 0.005 Lacunar stroke (period 2003–2008) 1.51 0.50 4.52 0.150 Nonlacunar 1.20 0.80 1.80 0.388 Undetermined 1.17 0.53 2.60 0.701 1.17 0.97 1.42 0.098 Hypertension 1.38 1.05 1.82 0.021 Diabetes 1.26 0.98 1.64 0.074 Hypercholesterolemia 0.76 0.60 0.96 0.023 Atrial fibrillation 1.29 1.02 1.63 0.036 Myocardial infarction 1.35 1.06 1.72 0.016 TIA 1.28 0.97 1.68 0.077 Antiplatelet agents 1.39 1.11 1.75 0.005 Antihypertensive treatment 1.02 0.66 1.59 0.925 Period 1991–1996 1.20 0.42 3.43 0.078 Period 1997–2002 0.49 0.18 1.31 0.204 Male sex Vascular risk factors Prestroke treatments Period 2003–2008 Hemiplegia 0.66 0.25 1.08 0.150 1.27 1.01 1.59 0.038 TIA indicates transient ischemic attack. Several factors were independently associated with the risk of poststroke dementia, including age, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, history of myocardial infarction, or hemiplegia at onset. Such associations have been previously described in the literature but with conflicting results.9,12,16 –18 In their meta-analysis, Pendlebury and Rothwell found that both diabetes and atrial fibrillation but neither hypertension nor previous ischemic heart disease were associated with poststroke dementia.2 In addition, they identified hemorrhagic stroke as a predictor of poststroke dementia, whereas lacunar stroke was associated with a nonsignificantly higher risk (OR, 0.8; 95% CI, 0.7 to 1.0; P⫽0.09). This contrasts with our findings, which show that lacunar stroke is a strong predictor of poststroke dementia with an OR of approximately 7. This association could be explained by the fact that patients with lacunar stroke frequently have many asymptom- 611 atic cerebral ischemic lesions, and it has been demonstrated that silent strokes increase the risk of poststroke dementia. Another explanation could be that these patients are already demented at the time of first clinical manifestation of stroke, but we cannot confirm this assumption because prestroke dementia was not recorded. Finally, the negative association between hypercholesterolemia and poststroke dementia must be interpreted with caution. Actually, we were not able to include statin treatment in the multivariable analysis because these data were not recorded in our files before 2006, and this treatment may influence the risk of dementia, although a recent meta-analysis suggested that statins are not effective in the prevention of dementia.19 The major strength of our study is the use of multiple overlapping sources of information to identify both hospitalized and nonhospitalized fatal and nonfatal strokes. Nevertheless, because no population screening was performed, undiagnosed strokes were not recorded. However, such cases are probably rare and did not affect our results. In addition, despite constant methodology for case ascertainment, it is possible that differences in case-finding effectiveness influenced our findings. The evaluation of poststroke dementia was based on the same criteria throughout the study period. Although Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Third and Fourth Edition criteria are less specific for the diagnosis of vascular dementia than other criteria such as National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke– Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l’Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINDS-AIREN) criteria,20 the fact that we maintained the same definition of poststroke dementia over the 24 years made it possible to analyze temporal changes in its prevalence. Because of the design of the study, the cognitive evaluation of patients was performed during the first month after the stroke, which is certainly early. Time from stroke was not entered into our model because these data were not recorded in our files. Data about long-term dementia were not available because active follow-up of patients was not systematically performed over the whole study period. However, several studies have suggested that cognitive disorders after the acute phase of stroke are associated with long-term poststroke dementia, which probably reflects poor cognitive reserve in patients with such impairments.21,22 Moreover, the primary aim of this study was to evaluate temporal trends in poststroke dementia, and because the methodology of case ascertainment was maintained over time, we can conclude that the changes observed were not biased. In addition, we did not consider the cognitive status of patients before stroke, which may explain why the prevalence of poststroke dementia observed in our study was higher than the 7% to 12% prevalence reported in population-based studies that excluded prestroke demented patients.23,24 Another limitation inherent to the use of prevalence as a measurement concerns the generalization of our results. This limitation, called length-biased sampling, stems from the fact that cases of poststroke dementia would overrepresent those who did not die during the first month (testable patients) but underrepresent those who died sooner (nontestable pa- 612 Stroke March 2011 tients).25 Lastly, although our study covered most causal assumptions to investigate an etiologic hypothesis with a cross-sectional design (population in a steady state, no selective survival, unchanged mean duration of outcome, no reverse causality, and temporal directionality), we preferred to interpret our measurements of association with caution by using prevalence ORs rather than incidence density ratios.26 To conclude, this study highlights temporal changes in the prevalence of early dementia after first-ever stroke over 24 years. These changes may be explained by concomitant determinants of survival and incidence, like stroke care management or prestroke medication. Acknowledgments We thank Mr Philip Bastable for reviewing the English. Sources of Funding Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 19, 2016 The Dijon Stroke Registry is supported by the French Institute for Public Health Surveillance (InVS) and Inserm. Disclosures None. References 1. Savva GM, Stephan BC; Alzheimer’s Society Vascular Dementia Systematic Review Group. Epidemiological studies of the effect of stroke on incident dementia: a systematic review. Stroke. 2010;41:e41– e46. 2. Pendlebury ST, Rothwell PM. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with pre-stroke and post-stroke dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1006 –1018. 3. Béjot Y, Rouaud O, Jacquin A, Osseby GV, Durier J, Manckoundia P, Pfitzenmeyer P, Moreau T, Giroud M. Stroke in the very old: incidence, risk factors, clinical features, outcomes and access to resources—a 22-year population-based study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;29:111–121. 4. Sudlow CL, Warlow CP. Comparing stroke incidence worldwide: what makes studies comparable? Stroke. 1996;27:550 –558. 5. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2000: Health Systems Improving Performance. Geneva: WHO; 2000. 6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (III ed, revised) (DSM-III-R). Washington, DC: APA; 1987. 7. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (IV ed) (DSM-IV). Washington, DC: APA; 1994. 8. Srikanth VK, Anderson JF, Donnan GA, Saling MM, Didus E, Alpitsis R, Dewey HM, Macdonell RA, Thrift AG. Progressive dementia after first-ever stroke: a community-based follow-up study. Neurology. 2004; 63:785–792. 9. Tang WK, Chan SS, Chiu HF, Ungvari GS, Wong KS, Kwok TC, Mok V, Wong KT, Richards PS, Ahuja AT. Frequency and determinants of poststroke dementia in Chinese. Stroke. 2004;35:930 –935. 10. del Ser T, Barba R, Morin MM, Domingo J, Cemillan C, Pondal M, Vivancos J. Evolution of cognitive impairment after stroke and risk factors for delayed progression. Stroke. 2005;36:2670 –2675. 11. Klimkowicz A, Dziedzic T, Slowik A, Szczudlik A. Incidence of pre- and poststroke dementia: Cracow stroke registry. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002;14:137–140. 12. Pohjasvaara T, Erkinjuntti T, Vataja R, Kaste M. Dementia three months after stroke. Baseline frequency and effect of different definitions of dementia in the Helsinki Stroke Aging Memory Study (SAM) cohort. Stroke. 1997;28:785–792. 13. Zhou DH, Wang JY, Li J, Deng J, Gao C, Chen M. Study on frequency and predictors of dementia after ischemic stroke: the Chongqing stroke study. J Neurol. 2004;251:421– 427. 14. Peters R, Beckett N, Forette F, Tuomilehto J, Clarke R, Ritchie C, Waldman A, Walton I, Poulter R, Ma S, Comsa M, Burch L, Fletcher A, Bulpitt C; HYVET investigators. Incident dementia and blood pressure lowering in the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial cognitive function assessment (HYVET-COG): a double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:683– 689. 15. Deschaintre Y, Richard F, Leys D, Pasquier F. Treatment of vascular risk factors is associated with slower decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73:674 – 680. 16. Inzitari D, Di Carlo A, Pracucci G, Lamassa M, Vanni P, Romanelli M, Spolveri S, Adriani P, Meucci I, Landini G, Ghetti A. Incidence and determinants of poststroke dementia as defined by an informant interview method in a hospital-based stroke registry. Stroke. 1998;29:2087–2093. 17. Barba R, Martínez-Espinosa S, Rodríguez-García E, Pondal M, Vivancos J, Del Ser T. Poststroke dementia: clinical features and risk factors. Stroke. 2000;31:1494 –1501. 18. Censori B, Manara O, Agostinis C, Camerlingo M, Casto L, Galavotti B, Partziguian T, Servalli MC, Cesana B, Belloni G, Mamoli A. Dementia after first stroke. Stroke. 1996;27:1205–1210. 19. McGuinness B, Craig D, Bullock R, Passmore P. Statins for the prevention of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD003160. 20. Wetterling T, Kanitz RD, Borgis KJ. Comparison of different diagnostic criteria for vascular dementia (ADDTC, DSM-IV, ICD-10, NINDSAIREN). Stroke. 1996;27:30 –36. 21. Rasquin SM, Lodder J, Visser PJ, Lousberg R, Verhey FR. Predictive accuracy of MCI subtypes for Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in subjects with mild cognitive impairment: a 2-year follow-up study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;19:113–119. 22. Nys GM, van Zandvoort MJ, de Kort PL, Jansen BP, de Haan EH, Kappelle LJ. Cognitive disorders in acute stroke: prevalence and clinical determinants. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23:408 – 416. 23. Kokmen E, Whisnant JP, O’Fallon WM, Chu CP, Beard CM. Dementia after ischemic stroke: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota (1960 –1984). Neurology. 1996;46:154 –159. 24. Kase CS, Wolf PA, Kelly-Hayes M, Kannel WB, Beiser A, D’Agostino RB. Intellectual decline after stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1998;29:805– 812. 25. Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. 26. Reichenheim ME, Coutinho ES. Measures and models for causal inference in cross-sectional studies: arguments for the appropriateness of the prevalence odds ratio and related logistic regression. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:66. Prevalence of Early Dementia After First-Ever Stroke: A 24-Year Population-Based Study Yannick Béjot, Corine Aboa-Eboulé, Jérôme Durier, Olivier Rouaud, Agnès Jacquin, Eddy Ponavoy, Dominique Richard, Thibault Moreau and Maurice Giroud Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on November 19, 2016 Stroke. 2011;42:607-612; originally published online January 13, 2011; doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595553 Stroke is published by the American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231 Copyright © 2011 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0039-2499. Online ISSN: 1524-4628 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/42/3/607 Data Supplement (unedited) at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/suppl/2012/02/26/STROKEAHA.110.595553.DC1.html http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/suppl/2012/03/12/STROKEAHA.110.595553.DC2.html Permissions: Requests for permissions to reproduce figures, tables, or portions of articles originally published in Stroke can be obtained via RightsLink, a service of the Copyright Clearance Center, not the Editorial Office. Once the online version of the published article for which permission is being requested is located, click Request Permissions in the middle column of the Web page under Services. Further information about this process is available in the Permissions and Rights Question and Answer document. Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at: http://www.lww.com/reprints Subscriptions: Information about subscribing to Stroke is online at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org//subscriptions/ Prevalencia de la demencia temprana tras un primer ictus Un estudio de base poblacional de 24 años Yannick Béjot, MD; Corine Aboa-Eboulé, MD; Jérôme Durier, MD; Olivier Rouaud, MD; Agnès Jacquin, MD; Eddy Ponavoy, MD; Dominique Richard, MD; Thibault Moreau, MD; Maurice Giroud, MD Antecedentes y objetivo—No existen datos acerca del cambio de la prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus a lo largo del tiempo. Nuestro objetivo fue evaluar las tendencias en la prevalencia de la demencia temprana post-ictus. Métodos—Entre 1985 y 2008, se registraron de forma global los primeros ictus aparecidos en la población de la ciudad de Dijon, Francia (150.000 habitantes). Se diagnosticó la presencia de demencia durante el primer mes siguiente al ictus, según los criterios del Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales, tercera y cuarta ediciones. Se analizaron las tendencias temporales para 4 periodos: 1985 a 1990, 1991 a 1996, 1997 a 2002 y 2003 a 2008. Se utilizó una regresión logística para los análisis no multivariados. Resultados—A lo largo de los 24 años, se registraron 3.948 primeros episodios de ictus. De los pacientes con ictus, 3.201 (81%) fueron evaluables, y de ellos 653 (20,4%) presentaron una demencia post-ictus (337 mujeres y 316 varones). La prevalencia de los casos no evaluables (en su mayor parte debidos a la muerte del paciente) se redujo del 28,0% al 10,2% (p < 0,0001). El análisis multivariable puso de manifiesto cambios temporales significativos en la prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus; la prevalencia en el segundo y cuarto periodos fue, respectivamente, de casi la mitad y el doble de la del primer periodo. La prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus asociada a los ictus lacunares fue 7 veces superior a la observada en la hemorragia intracerebral pero se redujo a lo largo del tiempo, y lo mismo ocurrió con la medicación antihipertensiva previa al ictus. La edad, diversos factores de riesgo vasculares, la hemiplejia y el uso de antiagregantes plaquetarios previo al ictus se asociaron a un aumento de la prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus. Conclusiones—Este estudio, que cubre un periodo de 24 años, resalta los cambios que se han producido a lo largo del tiempo en la prevalencia de la demencia temprana tras un primer ictus. Estos cambios pueden explicarse por factores determinantes concomitantes de la supervivencia y la incidencia, como el manejo del ictus o la medicación previa a éste. (Traducido del inglés: Prevalence of Early Dementia After First-Ever Stroke. A 24-Year Population-Based Study. Stroke. 2011;42:607-612.) Palabras clave: dementia n epidemiology n risk factors n stroke M ás allá de su efecto nocivo en las capacidades funcionales de los pacientes, el ictus se asocia también a un riesgo superior de deterioro cognitivo y demencia; los antecedentes de ictus aumentan a casi el doble el riesgo de demencia en la población de edad > 65 años1. La prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus ha sido objeto de una revisión reciente por parte de Pendlebury y Rothwell2. A pesar de la heterogeneidad en el diseño de los estudios y en las proporciones de distintos tipos de casos, los autores llegaron a la conclusión de que un 7% a 23% de los pacientes desarrollaban una demencia de nueva aparición en el primer año siguiente a un primer ictus. Se obtuvieron datos procedentes tanto de estudios de base hospitalaria como de estudios de base poblacional, pero todos estos estudios fueron de corta duración e incluyeron un número reducido de pacientes. Así pues, nin- guno de ellos aportaba datos fiables sobre los cambios de la prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus a lo largo del tiempo. Sin embargo, esta información es esencial para determinar el impacto que tiene el manejo agudo del ictus sobre la función cognitiva y para realizar proyecciones respecto a la carga que comportará el deterioro cognitivo post-ictus, con objeto de diseñar la política sanitaria adecuada. Por consiguiente, el objetivo de este estudio fue evaluar las tendencias en la prevalencia de la demencia temprana postictus, entre 1985 y 2008, basándonos en los datos del Dijon Stroke Registry. Métodos Se estudió la prevalencia de la demencia temprana tras un ictus en pacientes incluidos entre el 1 de enero de 1985 y Recibido el 2 de julio de 2010; versión final recibida el 5 de octubre de 2010; aceptado el 26 de octubre de 2010. Dijon Stroke Registry, EA4184 (Inserm e InVS; Y.B., C.A.-E., J.D., A.J., M.G.), IFR 100 (STIC-Santé), Faculty of Medicine, University of Burgundy and University Hospital of Dijon, Francia; y Centre Mémoire (Y.B., O.R., E.P., D.R., T.M., M.G.), Ressources et Recherche, Memory Clinic, University Hospital of Dijon, Dijon, Francia. Remitir la correspondencia a Yannick Bejot, MD, Dijon Stroke Registry, Service de Neurologie, Hôpital Général, 3 Rue du Faubourg Raines, 21033 Dijon, Francia. E-mail ybejot@yahoo.fr © 2011 American Heart Association, Inc. Stroke está disponible en http://www.stroke.ahajournals.org 67 DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.595553 68 Stroke Julio 2011 Figura 1. Prevalencia anual de la demencia post-ictus. Las barras verticales corresponden al IC del 95%. el 31 de diciembre de 2008 en el Dijon Stroke Registry de Dijon, Francia. Dicho registro cumple los criterios básicos definidos por Sudlow y Warlow para abordar un estudio “ideal” de la incidencia del ictus y presentan resultados fiables y que pueden ser comparados3,4. La población en estudio la formaron todos los residentes de la ciudad de Dijon (150.000 habitantes). Obtención de los datos Definición del ictus El ictus se definió según lo recomendado por la Organización Mundial de la Salud5. Los diagnósticos clínicos fueron validados mediante TC o RM3. Para este estudio sólo se tuvieron en cuenta los primeros episodios de ictus sintomático. La clasificación del subtipo de ictus utilizada desde 1985 fue la siguiente: (1) infarto lacunar; (2) ictus isquémico por embolia cardiaca; (3) ictus isquémico no lacunar y no cardioembólico; (4) hemorragia intracerebral espontánea; y (5) hemorragia subaracnoidea3. Identificación de los casos La información se obtuvo de múltiples fuentes solapadas3: (1) de los servicios de urgencias y de todos los departamentos clínicos y radiológicos del Dijon University Hospital, con diagnósticos de ictus realizados por un neurólogo; (2) de los 3 hospitales privados de la ciudad, con un diagnóstico realizado por un neurólogo privado; (3) del hogar del paciente o de las residencias de la ciudad, con diagnósticos realizados por médicos generales con la ayuda de una clínica ambulatoria con un neurólogo privado o de la sanidad pública; (4) de los 3 centros de radiología privados que identificaron casos que no habían sido detectados; (5) de los centros de ecografía Doppler del hospital universitario y de los centros privados; y (6) de los certificados de defunción obtenidos de la Oficina Local de Seguridad Social, que se encarga de registrar todas las muertes que se producen fuera del hospital para identificar los ictus mortales ocurridos en pacientes no hospitalizados. Todos los certificados de defunción recogidos fueron revisados por un miembro de nuestro equipo. Obtención de los datos de factores de riesgo vascular La información sobre los factores de riesgo vascular se obtuvo con la misma metodología durante todo el periodo de estudio 3. Registramos la presencia de hipertensión si se observaba una presión arterial elevada en los antecedentes patológicos del paciente (según lo referido por el propio paciente o lo que constaba en su historia clínica) o si el paciente estaba en tratamiento con antihipertensivos. Se registró la presencia de diabetes mellitus si se había anotado un nivel de glucemia ≥ 7,8 mmol/L en la historia clínica o si el paciente recibía tratamiento con insulina o hipoglucemiantes orales. Se consideró que había hipercolesterolemia si se registraba un nivel de colesterol total ≥ 5,7 mmol/L en los antecedentes patológicos del paciente o si el paciente recibía tratamiento hipolipemiante. Registramos también los antecedentes de fibrilación auricular, infarto de miocardio previo y antecedentes de ataque isquémico transitorio. El tabaquismo no se incluyó en el análisis final, ya que no se dispuso de datos al respecto en el 15% de los casos. Evaluación de la demencia post-ictus Dado el diseño del estudio y las limitaciones inherentes a ello, la evaluación de la función cognitiva fue realizada por un neurólogo en las fases iniciales del ictus, es decir, dentro del primer mes tras el inicio del ictus, con objeto de obtener la máxima información posible. Los pacientes y sus familiares acudieron a una entrevista y el diagnóstico de demencia post-ictus se basó en un enfoque clínico estandarizado sencillo, utilizando el Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales, tercera y cuarta ediciones6,7. Así pues, se estableció el diagnóstico de demencia si, según el informante y según el examen del paciente, había múltiples déficits cognitivos, manifestados por pérdida de memoria asociada ≥ 1 alteración cognitiva, incluidas la alteración del lenguaje, apraxia, agnosia o alteración de la función ejecutiva, con un deterioro significativo de la función social o laboral, que supusiera un deterioro significativo respecto a un nivel previo de función. Béjot y cols. Prevalencia de la demencia temprana tras un primer ictus 69 Análisis estadístico La prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus se calculó mediante el cociente del número de pacientes con demencia post-ictus respecto al número total de primeros ictus en los pacientes evaluables. Se calculó un IC del 95% para todas las estimaciones. Representamos los datos gráficamente para cada año, con objeto de evaluar gráficamente las tendencias de la prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus a lo largo de 24 años. Dada la variación multimodal de la prevalencia a lo largo de los años (Figura), se dividió el periodo de tiempo en 4 intervalos de 6 años: 1985 a 1990, 1991 a 1996, 1997 a 2002 y 2003 a 2008, tomando el intervalo 1985 a 1990 como referencia. Las características basales utilizadas para los análisis fueron los datos demográficos, los factores de riesgo vascular, los tratamientos previos al ictus y las manifestaciones clínicas. Los datos sobre las estatinas se analizaron tan solo mediante un análisis univariable puesto que únicamente se habían registrado desde 2006. Las proporciones, las OR y las medias de las características basales se compararon para los pacientes con y sin demencia post-ictus con el empleo de la prueba de χ2, regresión logística y análisis de la varianza, respectivamente. Las asociaciones univariables entre edad, sexo, periodos de tiempo, factores de riesgo vascular, tratamientos previos al ictus, subtipos de ictus, manifestaciones clínicas iniciales y demencia post-ictus se analizaron con una regresión logística para estimar las OR sin ajustar. Para los análisis multivariados, introdujimos en los modelos la edad, el sexo y también todos los posibles factores de confusión con un valor de probabilidad < 0,20 en el análisis univariable. Investigamos si había tendencias no lineales a lo largo de los periodos de estudio (prevalencia desigual en los distintos periodos) para la edad, el tratamiento previo al ictus, los subtipos de ictus, los factores de riesgo vascular y las características clínicas, como se observaron en la prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus. Se realizó una prueba de cociente de probabilidades para examinar si el ajuste de los modelos anidados multivariables mejoraba con la inclusión de términos de interacción estadística de los periodos de estudio con las características basales. Ninguno de los términos de interacción estadística fue significativo excepto la del subtipo lacunar con los periodos de estudio (p < 0,0001) y la del tratamiento antihipertensivo previo con los periodos de estudio (p = 0,0061), que se tuvieron en cuenta junto con los efectos principales en los modelos multivariables finales. Los valores de probabilidad < 0,05 se consideraron estadísticamente significativos. El análisis estadístico se realizó con el programa STATA 10.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). Cuestiones éticas Nuestro registro fue aprobado por el Comité Ético Nacional y por el Instituto Francés de Vigilancia de la Salud Pública. Resultados A lo largo de todo el periodo de estudio, se incluyó en el registro a un total de 3.948 pacientes con un primer ictus (1.842 varones, 2.106 mujeres). De los pacientes con ictus, 3.201 (81%) fueron evaluables y se les incluyó en los análisis. Los casos en los que no fue posible evaluar los test del estado cognitivo de los pacientes (n = 747 [19%]) se debie- ron a una afasia grave (n = 66 [8,7%]) o a la muerte (n = 681 [91,3%]) en la fase aguda del ictus. La prevalencia de pacientes no evaluables se redujo en los sucesivos periodos de estudio, pasando del 28,0% en 1985 a 1990 al 24,7% en 1991 a 1996, el 15,5% en 1997 a 2002, y el 10,2% en 2003 a 2008 (p < 0,0001). Los pacientes no evaluables eran de mayor edad (79,1 ± 12,5 años) que los evaluables (72,9 ± 14,7; p < 0,0001) y la edad aumentaba a lo largo de los 4 periodos de estudio sucesivos (77,4 ± 11,7, 78,6 ± 12,5, 81,1 ± 12,5 y 81,3 ± 13,0 años, respectivamente; p = 0,004) al contrario de lo que ocurría en los pacientes evaluables (72,0 ± 14,6, 73,6 ± 13,9, 72,8 ± 14,9 y 73,0 ± 15,0 años, respectivamente; p = 0,261). Tenían una forma de presentación inicial más grave, una mayor frecuencia de ataques isquémicos transitorios previos, infartos de miocardio o tratamiento anticoagulante, pero tenían una prevalencia inferior de hipercolesterolemia y de uso previo de medicación antiagregante plaquetaria que los pacientes evaluables (p < 0,05). De los pacientes evaluables, 653 (20,4%) presentaron demencia post-ictus (337 mujeres y 316 varones). La distribución de la prevalencia anual de la demencia post-ictus mostró aproximadamente una curva trimodal, con 3 picos, en 1990 (25,6%), 1998 (21,8%) y 2003 (25,2%), con reducciones diversas de la prevalencia entre ellos (Figura). No hubo un cambio significativo a lo largo del tiempo (p = 0,123) en la prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus a lo largo de los 4 periodos de estudio sucesivos, con valores del 23,7% (IC del 95%, 20,4% a 27%), 19,3% (16,4% a 22,3%), 19% (16,4% a 21,6%) y 20,2% (17,8% a 22,7%), respectivamente. Los pacientes con demencia post-ictus diferían de los pacientes sin demencia post-ictus. Eran de mayor edad (77,3 ± 10,8 años frente a 71,7 ± 15,4 años, p = 0,0001); tenían una mayor prevalencia de varios factores de riesgo vascular, como hipertensión, diabetes, fibrilación auricular, infarto de miocardio previo y antecedentes de ataque isquémico transitorio; y era más probable que hubieran recibido medicaciones preventivas para el ictus, incluidos los antiagregantes plaquetarios y el tratamiento antihipertensivo (Tabla 1). Además, era más probable que presentaran hemiplejia al ingreso, y había una mayor prevalencia de ictus lacunares, pero una prevalencia inferior de hemorragia intracerebral, hemorragia subaracnoidea e ictus isquémico no lacunar y no cardioembólico en esos pacientes (Tabla 1). El uso de anticoagulantes y antiagregantes plaquetarios previo al ictus en el conjunto de la población en estudio mostró una tendencia lineal, pasando del 2,8% y 5,8%, respectivamente, en el primer periodo, al 9,2% y 25,7% en el último periodo (p < 0,0001). Sin embargo, el uso de tratamiento antihipertensivo mostró una tendencia no lineal, con porcentajes del 48,1%, 53,4%, 51,0% y 45,6% a lo largo de los 4 periodos (p = 0,003). Los análisis multivariados revelaron un cambio significativo a lo largo del tiempo en la prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus en el segundo (1991 a 1996) y cuarto periodos (2003 a 2008), en comparación con el primero (1985 a 1990). La prevalencia en el segundo periodo fue de casi la mitad de la existente en el primero, mientras que la prevalencia en el cuarto periodo fue del doble de la del primero. La prevalencia en el tercer periodo fue la misma que en el primero (p < 0,0001). Diversas variables conservaron la significación 70 Stroke Julio 2011 Tabla 1. Características de los pacientes con y sin demencia post-ictus Ausencia de trastorno cognitivo post-ictus (N = 2.548) Número % IC del 95% Trastorno cognitivo post-ictus frente a ausencia de trastorno cognitivo post-ictus Trastorno cognitivo post-ictus (N = 653) Número % IC del 95% OR IC del 95% P Edad, años < 40 119 4,7% 3,9% 5,5% 3 0,5% 0,0% 1,0% 0,09 0,03 0,29 0,001 40–50 147 5,8% 4,9% 6,7% 9 1,4% 0,5% 2,3% 0,22 0,11 0,44 0,001 50–60 234 9,2% 8,1% 10,3% 29 4,4% 2,9% 6,0% 0,45 0,30 0,67 0,001 60–70 424 16,6% 15,2% 18,1% 91 13,9% 11,3% 16,6% 0,79 0,62 1,01 0,064 70–80 751 29,5% 27,7% 31,2% 218 33,4% 29,8% 37,0% 1,21 1,01 1,45 0,038 > 80 873 34,3% 32,4% 36,1% 303 46,4% 42,6% 50,2% 1,66 1,40 1,98 0,001 1.188 46,6% 44,7.% 48,6% 316 48,4% 44,5% 52,2% 1,08 0,91 1,28 0,37 238 9,3% 8,2% 10,5% 28 4,3% 2,7% 5,8% 0,47 0,32 0,70 0,001 85 3,3% 2,6% 4,0% 3 0,5% 0,0% 1,0% 0,13 0,04 0,42 0,001 Sexo masculino Subtipo de ictus Hemorragia intracerebral Hemorragia subaracnoidea Ictus isquémico Lacunares 554 21,7% 20,1% 23,3% 333 51,0% 47,2% 54,8% 3,57 2,99 4,27 0,001 Cardioembólicos 394 15,5% 14,1% 16,9% 96 14,7% 12,0% 17,4% 1,01 0,80 1,28 0,94 1.210 47,5% 45,5% 49,4% 184 28,2% 24,7% 31,6% 0,43 0,36 0,52 0,001 67 2,6% 2,0% 3,3% 9 1,4% 0,5% 2,3% 0,57 0,29 1,11 0,10 No lacunares no cardioembólicos Indeterminados Factores de riesgo vascular 1.624 63,7% 61,9% 65,6% 483 74,0% 70,6% 77,3% 1,58 1,31 1,91 0,001 Diabetes 358 14,1% 12,7% 15,4% 114 17,5% 14,5% 20,4% 1,30 1,04 1,63 0,024 Hipercolesterolemia 631 24,8% 23,1% 26,4% 139 21,3% 18,1% 24,4% 0,82 0,67 1,01 0,064 Fibrilación auricular 445 17,5% 16,0% 18,9% 147 22,5% 19,3% 25,7% 1,42 1,15 1,75 0,001 Infarto de miocardio 403 15,8% 14,4% 17,2% 153 23,4% 20,2% 26,7% 1,61 1,30 1,98 0,001 AIT 280 11,0% 9,8% 12,2% 104 15,9% 13,1% 18,7% 1,50 1,17 1,91 0,001 Hipertensión Tratamientos previos al ictus Anticoagulantes 158 6,2% 5,3% 7,1% 33 5,1% 3,4% 6,7% 0,79 0,54 1,16 0,24 Antiagregantes plaquetarios 501 19,7% 18,1% 21,2% 175 26,8% 23,4% 30,2% 1,52 1,25 1,85 0,001 Tratamiento antihipertensivo 1.225 48,1% 46,1% 50,0% 356 54,5% 50,7% 58,3% 1,26 1,07 1,50 0,007 46 10,6% 7,7% 13,6% 5 5,4% 0,7% 10,2% 0,48 0,19 1,25 0,13 Estatinas (2006–2008) Manifestaciones clínicas al inicio Coma Hemiplejia Confusión Lesión de hemisferio izquierdo 101 4,0% 3,2% 4,7% 26 4,0% 2,5% 5,5% 1,07 0,70 1,64 0,77 1.806 70,9% 69,1% 72,6% 522 79,9% 76,9% 83,0% 1,63 1,32 2,01 0,001 259 10,2% 9,0% 11,3% 79 12,1% 9,6% 14,6% 1,19 0,91 1,55 0,21 1.103 43,3% 41,4% 45,2% 290 44,4% 40,6% 48,2% 1,03 0,87 1,22 0,74 AIT indica ataque isquémico transitorio. estadística en el modelo multivariable (Tabla 2). La edad mostró una correlación intensa con la demencia post-ictus, con un aumento relativo del 3% por cada año más de edad. La prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus en los pacientes con ictus lacunar fue de 7 veces la observada en los pacientes con hemorragia intracerebral. Los análisis específicos por estratos según el periodo revelaron una disminución significativa a lo largo del tiempo en la prevalencia de demencia post-ictus entre los pacientes con ictus lacunar, en comparación con los pacientes sin este diagnóstico. La hipertensión, el infarto de miocardio previo, la presencia de hemiplejia al inicio y el tratamiento previo al ictus con antiagregantes plaquetarios se asociaron a un aumento de la prevalencia de demencia postictus. En cambio, la prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus en los pacientes con hipercolesterolemia fue un 24% inferior a la observada en los pacientes sin hipercolesterolemia. Globalmente, el tratamiento antihipertensivo no se asoció a la demencia post-ictus. Sin embargo, los análisis específicos por estratos según el periodo mostraron una disminución significativa a lo largo del tiempo en el riesgo de demencia postictus durante los dos últimos periodos (1997 a 2002 y 2003 a 2008) en los pacientes que habían sido tratados anteriormente con medicación antihipertensiva en comparación con los que no habían recibido este tratamiento. Béjot y cols. Prevalencia de la demencia temprana tras un primer ictus 71 Tabla 2. Análisis multivariado de los factores predictivos de la demencia post-ictus OR IC del 95% P Periodo de tiempo 1985–1990 1,00 1991–1996 0,52 0,30 0,90 0,018 1997–2002 1,14 0,72 1,81 0,576 2003–2008 1,91 1,25 2,91 0,003 Período de tiempo (continuo) 1,03 1,01 1,06 0,003 Edad (continuo) 1,03 1,02 1,04 0,001 Subtipo de ictus Hemorragia intracerebral 1,00 Hemorragia subaracnoidea 0,47 0,14 1,60 0,225 Ictus lacunar 7,24 4,13 12,69 0,000 Ictus lacunar (periodo 1991–1996) 10,01 3,16 31,75 0,000 Ictus lacunar (periodo 1997–2002) 5,86 1,92 17,86 0,005 Ictus lacunar (periodo 2003–2008) 1,51 0,50 4,52 0,150 No lacunar 1,20 0,80 1,80 0,388 Indeterminado 1,17 0,53 2,60 0,701 1,17 0,97 1,42 0,098 Hipertensión 1,38 1,05 1,82 0,021 Diabetes 1,26 0,98 1,64 0,074 Sexo masculino Factores de riesgo vascular Hipercolesterolemia 0,76 0,60 0,96 0,023 Fibrilación auricular 1,29 1,02 1,63 0,036 Infarto de miocardio 1,35 1,06 1,72 0,016 AIT 1,28 0,97 1,68 0,077 Antiagregantes plaquetarios 1,39 1,11 1,75 0,005 Tratamiento antihipertensivo 1,02 0,66 1,59 0,925 Periodo 1991-1996 1,20 0,42 3,43 0,078 Periodo 1997-2002 0,49 0,18 1,31 0,204 Periodo 2003-2008 0,66 0,25 1,08 0,150 1,27 1,01 1,59 0,038 Tratamientos previos al ictus Hemiplejia AIT indica ataque isquémico transitorio. Discusión Éste es el primer estudio en el que se evalúan las tendencias temporales de la demencia temprana tras el ictus a lo largo de 24 años, utilizando una metodología constante para la identificación del ictus y la misma definición de la demencia en todo el periodo de estudio. La prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus observada en este estudio es similar a la descrita en los estudios de base hospitalaria, con la inclusión de los primeros ictus y la demencia previa al ictus. En su metanálisis, Pendlebury y Rothwell estimaron a partir de estos estudios una prevalencia general del 26,5% (IC del 95%, 24,3% a 28,7%) con independencia del tiempo transcurrido desde el inicio del ictus2. En cambio, en el único estudio de base poblacional que incluyó los primeros ictus y que no excluyó la demencia previa al ictus, se obser- vó una prevalencia inferior, del 12,5% (IC del 95%, 5,6% a 19,4%)8. Sin embargo, había algunas diferencias en la metodología aplicada que pueden explicar tales discrepancias entre los resultados de este estudio y las del nuestro. En el estudio citado, la evaluación cognitiva se realizó a 1 año, y los pacientes con ictus eran de menor edad que los de nuestro registro. En otros varios estudios se ha evaluado la prevalencia de la demencia en los 3 primeros meses siguientes al inicio del ictus. En ellos se observó una frecuencia que oscilaba entre el 18,7% y el 21,2%, lo cual concuerda con nuestros resultados, a pesar de que se tratara de un contexto de base hospitalaria9 –13. Aunque pareció mantenerse estable a lo largo del tiempo, el análisis multivariable puso de relieve que la prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus cambió en el segundo (1991 a 1996) y en el cuarto (2003 a 2008) periodos. De hecho, fue de la mitad y el doble, respectivamente, de la prevalencia observada en el primer periodo. Investigamos si estas tendencias podían observarse también para la edad, el tratamiento previo al ictus, los subtipos de ictus, los factores de riesgo vascular y las manifestaciones clínicas. No se observó ningún cambio a lo largo del tiempo en lo relativo a la edad en los pacientes evaluables, pero hubo un aumento de la edad en los sucesivos periodos de estudio en los pacientes no evaluables. Además, el ictus lacunar y el tratamiento antihipertensivo se asociaron a una reducción significativa a lo largo del tiempo en la prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus. Las explicaciones teóricas de estos estudios pueden estar en los cambios de la prevalencia de la demencia previa al ictus, en la incidencia de demencia postictus y/o en la supervivencia tras el ictus. La reducción de la prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus en el segundo periodo (1991 a 1996), en comparación con el primero (1985 a 1990), puede explicarse por el hecho de que este periodo podría haber sido de transición. Según lo observado en el primer periodo, la prevalencia de pacientes no evaluables, debido principalmente a la muerte temprana, se mantuvo elevada (25%), y ello redujo el número de casos prevalentes que podrían haber presentado una demencia post-ictus si hubieran sobrevivido, sobre todo teniendo en cuenta que estos pacientes eran de mayor edad, tenían una forma de presentación clínica más grave y tenían más factores de riesgo vascular, por lo que su riesgo de demencia era elevado. En paralelo con ello, la frecuencia de los tratamientos preventivos previos al ictus, que se sabe que reducen el riesgo de demencia14,15, mostró un notable aumento durante este segundo periodo, y puede haber contribuido a reducir tanto la prevalencia de la demencia previa al ictus como la incidencia de la demencia post-ictus. En consecuencia, tanto el bajo número de casos prevalentes como la menor incidencia de demencia post-ictus pueden haber comportado una prevalencia significativamente inferior de demencia post-ictus. Por el contrario, el tercer (1997 a 2002) y el cuarto (2003 a 2008) periodos se asociaron a una prevalencia inferior de pacientes no evaluables, debido a una disminución de la letalidad temprana, posiblemente a causa de un mejor manejo agudo del ictus. La consecuencia puede haber sido un mayor número de casos prevalentes de demencia post-ictus. Además, a diferencia del uso de anticoagulantes y antiagregantes plaquetarios, no se demostró que el uso de tratamientos para la hipertensión antes del ictus tuviera una tendencia lineal, sino que disminuyó durante los 2 últimos periodos, y ello 72 Stroke Julio 2011 puede haber contribuido a aumentar la prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus. Varios factores se asociaron de manera independiente al riesgo de demencia post-ictus: edad, hipertensión, fibrilación auricular, antecedentes de infarto de miocardio o hemiplejia al inicio. Estas asociaciones se han descrito anteriormente en la literatura, aunque con resultados contradictorios9,12,16–18. En su metanálisis, Pendlebury y Rothwell observaron que tanto la diabetes como la fibrilación auricular, pero no así la hipertensión ni la cardiopatía isquémica previa, se asociaron a la demencia post-ictus2. Además, estos autores identificaron que el ictus hemorrágico era un factor predictivo de la demencia post-ictus, mientras que el ictus lacunar se asociaba a un riesgo superior pero sin diferencia significativa (OR, 0,8; IC del 95%, 0,7 a 1,0; p = 0,09). Esto contrasta con nuestros resultados, que muestran que el ictus lacunar es un predictor potente de la demencia post-ictus, con una OR de aproximadamente 7. Esta asociación podría explicarse por el hecho de que los pacientes con ictus lacunar presentan con frecuencia muchas lesiones isquémicas cerebrales asintomáticas, y se ha demostrado que los ictus silentes aumentan el riesgo de demencia post ictus. Otra explicación podría ser que estos pacientes sufran ya una demencia en el momento de la primera manifestación clínica de ictus, pero no podemos confirmar esta suposición, ya que no se registró la demencia previa al ictus. Por último, la asociación negativa entre hipercolesterolemia y demencia post-ictus debe interpretarse con precaución. De hecho, no pudimos incluir el tratamiento con estatinas en el análisis multivariable porque estos datos no se incluyeron en nuestro registro antes de 2006, y este tratamiento puede influir en el riesgo de demencia, aunque un metanálisis reciente ha sugerido que las estatinas no son eficaces en la prevención de la demencia19. El principal punto fuerte de nuestro estudio es el uso de múltiples fuentes de información solapadas para identificar los ictus mortales y no mortales, tanto hospitalizados como no hospitalizados. No obstante, puesto que no se realizó un examen de detección sistemática en la población, no se registraron los ictus no diagnosticados. Sin embargo, estos casos son probablemente muy poco frecuentes y no afectaron a nuestros resultados. Además, a pesar del empleo de una metodología constante para la identificación de los casos, es posible que las diferencias en la efectividad de la identificación de los casos influyeran en nuestros resultados. La evaluación de la demencia post-ictus se basó en los mismos criterios durante todo el periodo de estudio. Aunque los criterios del Manual Diagnóstico y Estadístico de los Trastornos Mentales, tercera y cuarta ediciones, son menos específicos para el diagnóstico de la demencia vascular que otros criterios como los del National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke–Association Internationale pour la Recherche et l’Enseignement en Neurosciences (NINDS-AIREN)20, el hecho de que mantuviéramos la misma definición de la demencia post-ictus a lo largo de 24 años hizo posible analizar los cambios de la prevalencia a lo largo del tiempo. Dado el diseño del estudio, la evaluación cognitiva de los pacientes se realizó durante el primer mes siguiente al ictus, lo cual es ciertamente una evaluación temprana. El tiempo transcurrido desde el ictus no se introdujo en nuestro modelo por- que esos datos no constaban en nuestro registro. No se dispuso de datos relativos a la demencia a largo plazo porque no se realizó un seguimiento activo de los pacientes de manera sistemática a lo largo de todo el periodo de estudio. Sin embargo, varios estudios han sugerido que los trastornos cognitivos tras la fase aguda del ictus se asocian a la demencia post-ictus a largo plazo, lo cual refleja probablemente una baja reserva cognitiva en pacientes con estos deterioros21,22. Además, el objetivo principal de este estudio fue evaluar las tendencias temporales de la demencia post-ictus, y puesto que la metodología de la identificación de los casos se mantuvo a lo largo del tiempo, podemos concluir que los cambios observados no estaban sesgados. Además, no tuvimos en cuenta el estado cognitivo de los pacientes antes del ictus, y ello puede explicar por qué la prevalencia de la demencia post-ictus observada en nuestro estudio fue superior a la prevalencia del 7% al 12% descrita en los estudios de base poblacional en los que se excluyó a los pacientes con demencia previa al ictus23,24. Otra limitación inherente al uso de la prevalencia como parámetro de medición es la relativa a la generalización de nuestros resultados. Esta limitación, denominada muestreo con sesgo de duración, deriva del hecho de que en los casos de demencia post-ictus estarían sobrerrepresentados los pacientes que no fallecían durante el primer mes (pacientes evaluables) y estarían infrarrepresentados los pacientes que fallecían antes de ese plazo (pacientes no evaluables)25. Por último, aunque nuestro estudio abordó la mayor parte de las asunciones causales para investigar una hipótesis etiológica con un diseño transversal (población en un estado estable, ausencia de supervivencia selectiva, sin cambios en la duración media del parámetro de valoración, ausencia de causalidad inversa y direccionalidad temporal) preferimos interpretar nuestras medidas de la asociación con precaución, utilizando las OR de prevalencia en vez de las relaciones de densidad de incidencia26. Como conclusión, este estudio resalta los cambios a lo largo del tiempo de la prevalencia de la demencia temprana tras un primer ictus, durante 24 años. Estos cambios pueden explicarse por los factores determinantes concomitantes de la supervivencia y la incidencia, como el manejo del ictus y la medicación previa a éste. Agradecimientos Damos las gracias al El Sr. Philip Bastable por la revisión del texto inglés. Fuentes de financiación El Dijon Stroke Registry es financiado por el Instituto Francés de Vigilancia de Salud Pública (InVS) y el Inserm. Declaraciones de conflictos de intereses Ninguna. Bibliografía 1. Savva GM, Stephan BC; Alzheimer’s Society Vascular Dementia Systematic Review Group. Epidemiological studies of the effect of stroke on incident dementia: a systematic review. Stroke. 2010;41:e41– e46. 2. Pendlebury ST, Rothwell PM. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with pre-stroke and post-stroke dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1006 –1018. 3. Béjot Y, Rouaud O, Jacquin A, Osseby GV, Durier J, Manckoundia P, Pfitzenmeyer P, Moreau T, Giroud M. Stroke in the very old: incidence, risk factors, clinical features, outcomes and access to resources—a 22-year population-based study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;29:111–121. 4. Sudlow CL, Warlow CP. Comparing stroke incidence worldwide: what makes studies comparable? Stroke. 1996;27:550 –558. 5. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2000: Health Systems Improving Performance. Geneva: WHO; 2000. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. tematic Review Group. Epidemiological studies of the effect of stroke on incident dementia: a systematic review. Stroke. 2010;41:e41– e46. Pendlebury ST, Rothwell PM. Prevalence, incidence, and factors associated with pre-stroke and post-stroke dementia: a systematic and Béjot review y cols. meta-analysis. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:1006 –1018. Béjot Y, Rouaud O, Jacquin A, Osseby GV, Durier J, Manckoundia P, Pfitzenmeyer P, Moreau T, Giroud M. Stroke in the very old: incidence, risk factors, clinical features, outcomes and access to resources—a 22-year population-based study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2010;29:111–121. Sudlow CL, Warlow CP. Comparing stroke incidence worldwide: what makes studies comparable? Stroke. 1996;27:550 –558. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2000: Health Systems Improving Performance. Geneva: WHO; 2000. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (III ed, revised) (DSM-III-R). Washington, DC: APA; 1987. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (IV ed) (DSM-IV). Washington, DC: APA; 1994. Srikanth VK, Anderson JF, Donnan GA, Saling MM, Didus E, Alpitsis R, Dewey HM, Macdonell RA, Thrift AG. Progressive dementia after first-ever stroke: a community-based follow-up study. Neurology. 2004; 63:785–792. Tang WK, Chan SS, Chiu HF, Ungvari GS, Wong KS, Kwok TC, Mok V, Wong KT, Richards PS, Ahuja AT. Frequency and determinants of poststroke dementia in Chinese. Stroke. 2004;35:930 –935. del Ser T, Barba R, Morin MM, Domingo J, Cemillan C, Pondal M, Vivancos J. Evolution of cognitive impairment after stroke and risk factors for delayed progression. Stroke. 2005;36:2670 –2675. Klimkowicz A, Dziedzic T, Slowik A, Szczudlik A. Incidence of pre- and poststroke dementia: Cracow stroke registry. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002;14:137–140. Pohjasvaara T, Erkinjuntti T, Vataja R, Kaste M. Dementia three months after stroke. Baseline frequency and effect of different definitions of dementia in the Helsinki Stroke Aging Memory Study (SAM) cohort. Stroke. 1997;28:785–792. Zhou DH, Wang JY, Li J, Deng J, Gao C, Chen M. Study on frequency and predictors of dementia after ischemic stroke: the Chongqing stroke study. J Neurol. 2004;251:421– 427. Peters R, Beckett N, Forette F, Tuomilehto J, Clarke R, Ritchie C, Waldman A, Walton I, Poulter R, Ma S, Comsa M, Burch L, Fletcher A, Bulpitt C; HYVET investigators. Incident dementia and blood pressure lowering in the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial cognitive function assessment (HYVET-COG): a double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:683– 689. Deschaintre Y, Richard F, Leys D, Pasquier F. Treatment of vascular risk factors is associated with slower decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73:674 – 680. Inzitari D, Di Carlo A, Pracucci G, Lamassa M, Vanni P, Romanelli M, Spolveri S, Adriani P, Meucci I, Landini G, Ghetti A. Incidence and determinants of poststroke dementia as defined by an informant interview method in a hospital-based stroke registry. Stroke. 1998;29:2087–2093. Barba R, Martínez-Espinosa S, Rodríguez-García E, Pondal M, Vivancos J, Del Ser T. Poststroke dementia: clinical features and risk factors. Stroke. 2000;31:1494 –1501. Censori B, Manara O, Agostinis C, Camerlingo M, Casto L, Galavotti B, Partziguian T, Servalli MC, Cesana B, Belloni G, Mamoli A. Dementia after first stroke. Stroke. 1996;27:1205–1210. McGuinness B, Craig D, Bullock R, Passmore P. Statins for the prevention of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD003160. Wetterling T, Kanitz RD, Borgis KJ. Comparison of different diagnostic criteria for vascular dementia (ADDTC, DSM-IV, ICD-10, NINDSAIREN). Stroke. 1996;27:30 –36. Rasquin SM, Lodder J, Visser PJ, Lousberg R, Verhey FR. Predictive accuracy of MCI subtypes for Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in subjects with mild cognitive impairment: a 2-year follow-up study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;19:113–119. Nys GM, van Zandvoort MJ, de Kort PL, Jansen BP, de Haan EH, Kappelle LJ. Cognitive disorders in acute stroke: prevalence and clinical determinants. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23:408 – 416. Kokmen E, Whisnant JP, O’Fallon WM, Chu CP, Beard CM. Dementia after ischemic stroke: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota (1960 –1984). Neurology. 1996;46:154 –159. Kase CS, Wolf PA, Kelly-Hayes M, Kannel WB, Beiser A, D’Agostino RB. Intellectual decline after stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1998;29:805– 812. Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. Reichenheim ME, Coutinho ES. Measures and models for causal inference in cross-sectional studies: arguments for the appropriateness of the prevalence odds ratio and related logistic regression. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:66. study. J Neurol. 2004;251:421– 427. 14. Peters R, Beckett N, Forette F, Tuomilehto J, Clarke R, Ritchie C, Waldman A, Walton I, Poulter R, Ma S, Comsa M, Burch L, Fletcher A, Bulpitt C; demencia HYVET investigators. Incident and blood pressure Prevalencia de la temprana trasdementia un primer ictus 73 lowering in the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial cognitive function assessment (HYVET-COG): a double-blind, placebo controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:683– 689. 15. Deschaintre Y, Richard F, Leys D, Pasquier F. Treatment of vascular risk factors is associated with slower decline in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2009;73:674 – 680. 16. Inzitari D, Di Carlo A, Pracucci G, Lamassa M, Vanni P, Romanelli M, Spolveri S, Adriani P, Meucci I, Landini G, Ghetti A. Incidence and determinants of poststroke dementia as defined by an informant interview method in a hospital-based stroke registry. Stroke. 1998;29:2087–2093. 17. Barba R, Martínez-Espinosa S, Rodríguez-García E, Pondal M, Vivancos J, Del Ser T. Poststroke dementia: clinical features and risk factors. Stroke. 2000;31:1494 –1501. 18. Censori B, Manara O, Agostinis C, Camerlingo M, Casto L, Galavotti B, Partziguian T, Servalli MC, Cesana B, Belloni G, Mamoli A. Dementia after first stroke. Stroke. 1996;27:1205–1210. 19. McGuinness B, Craig D, Bullock R, Passmore P. Statins for the prevention of dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD003160. 20. Wetterling T, Kanitz RD, Borgis KJ. Comparison of different diagnostic criteria for vascular dementia (ADDTC, DSM-IV, ICD-10, NINDSAIREN). Stroke. 1996;27:30 –36. 21. Rasquin SM, Lodder J, Visser PJ, Lousberg R, Verhey FR. Predictive accuracy of MCI subtypes for Alzheimer’s disease and vascular dementia in subjects with mild cognitive impairment: a 2-year follow-up study. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005;19:113–119. 22. Nys GM, van Zandvoort MJ, de Kort PL, Jansen BP, de Haan EH, Kappelle LJ. Cognitive disorders in acute stroke: prevalence and clinical determinants. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2007;23:408 – 416. 23. Kokmen E, Whisnant JP, O’Fallon WM, Chu CP, Beard CM. Dementia after ischemic stroke: a population-based study in Rochester, Minnesota (1960 –1984). Neurology. 1996;46:154 –159. 24. Kase CS, Wolf PA, Kelly-Hayes M, Kannel WB, Beiser A, D’Agostino RB. Intellectual decline after stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1998;29:805– 812. 25. Rothman KJ, Greenland S, Lash TL. Modern Epidemiology. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008. 26. Reichenheim ME, Coutinho ES. Measures and models for causal inference in cross-sectional studies: arguments for the appropriateness of the prevalence odds ratio and related logistic regression. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:66.