Burke, Anthony; Fishel, Stefanie; Mitchel, Audra; Dalby, Simon and Levine, Daniel J. (2016) Planet Politics A Manifesto from the End of IR

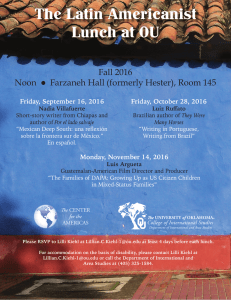

Anuncio