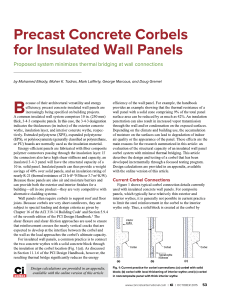

Cite this article Research Article Sok T and Lee SW (2021) A mechanistic approach to predict built-in temperature in concrete pavements. Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers – Transport 174(4): 227–238, https://doi.org/10.1680/jtran.18.00065 Paper 1800065 Received 15/04/2018; Accepted 26/07/2018; Published online 06/09/2018 Keywords: pavement design/roads & highways/thermal effects ICE Publishing: All rights reserved Transport A mechanistic approach to predict built-in temperature in concrete pavements Tetsya Sok MSc Seung Woo Lee PhD PhD candidate, Department of Civil Engineering, Gangneung-Wonju National University, Gangneung-si, Gangwon-do, South Korea Professor, Department of Civil Engineering, Gangneung-Wonju National University, Gangneung-si, Gangwon-do, South Korea (corresponding author: swl@gwnu.ac.kr) The built-in temperature difference (BITD), defined as the temperature difference between the top and bottom of a slab at the final setting time, is an important parameter for analysing curling stress and slab deformation in concrete pavements. However, the available methods for estimating this parameter are very limited. A method to predict the BITD in a concrete pavement was therefore developed. To do this, a numerical model was developed to predict the temperature distribution in a concrete slab at early age using a transient one-dimensional finite-difference method. A mathematical equation for predicting concrete final setting time presented in the literature was used and incorporated in the numerical model to predict the BITD. The results of the numerical model showed good agreement with field data. Using the proposed model, the effects of climatic conditions, placement time, pavement thickness and concrete mix proportion on the BITD were also evaluated. The results showed that climatic conditions, placement time and concrete mix proportion have substantial effects on the BITD, whereas pavement thickness has only a slight effect. The proposed model can be used to predict the BITD in concrete slabs for given concrete mix design, placement time, pavement thickness and environmental conditions. Notation Cc cc cp E FB Fcloud Hu hconv If i k kc kp pcem pC2S pC3A pC3S pC4AF pFA pFA-CaO pFreeCaO pMgO pslag pSO3 q qabs 3 cementitious materials content (kg/m ) heat capacity of concrete layer (J/kg.°C) specific heat of pavement material (J/kg.°C) activation energy (J/mol) Blaine fineness (m2/kg) cloud cover factor total heat of hydration of cementitious materials (J/kg) heat convection transfer coefficient (W/m2/°C) intensity factor node time step thermal conductivity of concrete layer (W/m.°C) thermal conductivity of pavement material (W/m.°C) weight ratio of cement to total cementitious content weight ratio of dicalcium silicate to total cement content weight ratio of tricalcium aluminate to total cement content weight ratio of tricalcium silicate to total cement content weight ratio of tetracalcium aluminoferrite to total cement content fly ash mass ratio to total cementitious content calcium oxide mass ratio to total fly ash content weight ratio of free calcium oxide to total cement content weight ratio of magnesium oxide to total cement content slag mass ratio to total cementitious content weight ratio of sulfate to total cement content rate of heat liberation during cement hydration (W/m3) solar absorption of concrete (W/m2) Downloaded by [] on [24/10/22]. Copyright © ICE Publishing, all rights reserved. qconv qir qsolar N R T Ta Tactual Tagg Tc Tcem Tconcrete Tdp Tr Ts Tset Tsky Tw t te vwind Wa Wc Ww Wwa x α αcr αu β Δt Δx Δxc heat convection transfer (W/m2) thermal irradiation from the surface (W/m2) peak solar radiation during daytime period (W/m2) cloud cover universal gas constant (8·3144 J/mol/K) pavement temperature (°C) air temperature (°C) actual concrete temperature (°C) temperature of aggregate (°C) nodal concrete slab temperature (°C) temperature of cement (°C) concrete placement temperature (°C) local dew point temperature (°C) reference concrete slab temperature (21·1°C) surface pavement temperature (°C) concrete temperature at final set (°C) effective sky temperature (K ) temperature of water (°C) time (s) equivalent age of concrete (h) wind speed (m/s) weight of dry aggregate (kg/m3) weight of cement (kg/m3) weight of water (kg/m3) weight of wet aggregate (kg/m3) depth below pavement surface (m) degree of hydration critical degree of hydration ultimate degree of hydration hydration shape model time increment (s) space increment of pavement layers (m) space increment of concrete layer (m) 227 Transport Volume 174 Issue 4 δsurface εsky εp γabs ρ ρc σ τ 1. (differential) pavement thickness for the energy balance (m) sky emissivity surface emissivity solar absorptivity of concrete density of pavement material (kg/m3) density of concrete layer (kg/m3) Stefan–Boltzmann constant (5·669 10−8 W/m−2.K−4) hydration time parameter (h) ΔTset > 0 Temperature difference = +ΔTset BITD = +ΔTset (a) ΔTactual = 0 Introduction In a concrete pavement, the presence of a temperature difference between its top and bottom causes curling deformation and stresses (Westergaard, 1926). A slab can curl upwards or downwards depending on whether the magnitude of the temperature difference is negative (i.e. when the slab surface is cooler than the bottom) or positive (i.e. when the slab surface is warmer than the bottom). Since a slab is not free to curl due to restraint from its self-weight, tensile stresses are generated in the slab (Westergaard, 1926). In addition, a concrete slab curls upwards when there is a moisture difference between the top surface and the bottom of the slab. Moisture differences are caused by drying of the top of the slab surface, but below about 50 mm from the surface, the moisture level remains at a relatively constant high level even in very dry areas (ARA, 2002). This leads to concrete slabs curling upwards. The amount of drying shrinkage in the upper portion of a concrete slab depends on various influencing factors, such as the curing method and concrete mixture properties. When a slab curls upwards due to the presence of a negative temperature gradient combined with moisture warping, the edges of the slab do not contact the ground, thus leaving a portion of the slab unsupported (ARA, 2002). When a concrete pavement slab is initially placed, the temperature difference through its depth is always zero. However, if the air temperature is warmer than the concrete temperature, the temperature of the top part of the slab starts to increase before the concrete hardens. In this period, the concrete is plastic and does not have sufficient structural integrity to deform or change shape as the temperature difference develops. When concrete first begins to set and harden, a large positive temperature difference can develop in a flat slab, without deformation occurring. In this situation, the concrete slab is in full contact with the foundation and is in a zero-stress condition even if there is a temperature or moisture gradient through the slab because the concrete is just leaving the plastic state, as shown in Figure 1(a). Another situation when a large positive temperature difference would develop in a flat slab is when a concrete pavement is placed during the morning of a hot sunny day. This condition tends to expose the freshly paved concrete slab to a large temperature gradient from intense solar radiation plus the heat of hydration (ARA, 2002). When the actual temperature gradient through the slab becomes zero later on, the slab will attempt to curl upwards, analogous to a slab with a negative temperature gradient (Figure 1(b)). 228 A mechanistic approach to predict built-in temperature in concrete pavements Sok and Lee Downloaded by [] on [24/10/22]. Copyright © ICE Publishing, all rights reserved. Actual temperature difference = 0 Equivalent temperature difference = –ΔTset (b) Figure 1. Illustration of a positive built-in temperature gradient in a concrete slab: (a) zero-stress condition; (b) zero gradient but stressed condition On the other hand, if a concrete pavement slab is placed later in the afternoon or at night, the highest temperature from the heat of hydration does not coincide with the most intense solar radiation (ARA, 2002). This can lead to a lower temperature difference or a potentially negative difference, as shown in Figure 2(a). The slab will attempt to curl downwards if the actual temperature difference is larger than the built-in temperature difference (BITD), as shown in Figure 2(b). Previous studies have shown that the BITD is a critical input parameter for the performance of a concrete pavement predicted using the Mechanistic–Empirical Pavement Design Guide (MEPDG) (Coree, 2005; Hall and Beam, 2004; Kannekanti ΔTset > 0 Temperature difference = –ΔTset BITD = –ΔTset (a) ΔTactual = 0 Actual temperature difference = 0 Equivalent temperature difference = +ΔTset (b) Figure 2. Illustration of a negative built-in temperature gradient in a concrete slab: (a) zero-stress condition; (b) zero gradient but stressed condition Transport Volume 174 Issue 4 A mechanistic approach to predict built-in temperature in concrete pavements Sok and Lee and Harvey, 2005). According to Yu and Khazanovich (2001), in an analysis of temperature effects in concrete pavements, the actual temperature difference in a concrete slab can be added to the BITD to obtain the total effective temperature difference. incorporating the given initial and boundary conditions (Narasimhan, 1999). The 1D heat-transfer equation is Currently, there are no available methods or guidelines to estimate the BITD in concrete pavements. According to the MEPDG, the BITD has significant effects on the behaviour and performance of concrete pavements. The BITD is determined, by calibration, to minimise the differences between predicted and observed distresses. This BITD can then be used as the default value for general concrete pavements. where kp is the thermal conductivity of the pavement material (W/m.°C), ρ is density (kg/m3), cp is specific heat (J/kg.°C), T is temperature (°C), t is time (s), x is the depth below the pavement surface (m) and q is the heat generated heat from the cement hydration process (W/m3). Hansen et al. (2006) quantified the magnitude of the BITD by measuring the temperature distribution in concrete pavements together with final set time, which was determined based on the standard test method for the setting time of concrete mixtures by penetration resistance (ASTM, 2008) in the laboratory then converting to the final setting time of a field concrete pavement using the maturity concept. Other researchers have used back-calculation methods on in-service pavement sections to determine the amount of permanent curl or uplift (BITD combined with drying shrinkage gradient and its associated creep effect) using a combination of the finite-element method coupled with surface profile measurements of concrete slabs in the field (Rao et al., 2001; Wells et al., 2006; Yu et al., 1998). According to Wells et al. (2006) and Nassiri and Vandenbossche (2012), the built-in curling temperature is defined at the time corresponding to when expansion/contraction is measured with changes in slab temperature. Although methods to determine the BITD have been proposed, they are very costly and require experimental data collected in the field. A practical and simple method to estimate the realistic BITD in concrete pavements is thus still required. The major objective of this study was to develop a mechanistic approach to predict the built-in temperature distribution in concrete pavements. To do this, a one-dimensional (1D) heattransfer model to simulate concrete pavement temperature using the finite-difference method was developed. Existing mathematical equations for computing the rate of heat liberation from cement hydration and the final setting time of concrete were integrated into the developed model to establish the BITD. Using the proposed model, the effects of climatic conditions, concrete placement time, concrete mix proportion and pavement thickness on the BITD in concrete pavement slabs were also evaluated. 1: kp @2T @T þ q ¼ ρcp @x2 @t The heat of hydration q, which is influenced by a number of factors including cement chemical composition, cement fineness and concrete mixture proportions, can be defined using the regression model developed by Schindler and Folliard (2005). Equation 1 accounts for the temperature fluctuation in the environment, underlying layer properties and the properties of the pavement slab. For a concrete slab placed under field conditions, heat will be transferred to and from its surroundings. This heat transfer can take place in four different ways (conduction, convection, irradiation and solar absorption), as shown in Figure 3. 2.2 Heat of hydration The cement hydration reaction is an exothermic process and is a critical factor for field concrete temperature predictions. The rate of heat generation is the numerical differentiation of the heat evolution curve with respect to time. The regression model developed by Schindler and Folliard (2005) was used in this study, which is written as 2: qðtÞ ¼ Hu Cc β τ β E 1 1 αðte Þ exp te te R 273 þ Tr 273 þ Tc Solar radiation Wind Heat convection Incoming and outgoing radiation Concrete slab +X Sub-base Heat conduction Subgrade 2. Mechanistic modelling of BITD 2.1 Heat-transfer model of pavement structure In a concrete pavement, the temperature distribution can be calculated by solving the 1D heat-transfer equation by Downloaded by [] on [24/10/22]. Copyright © ICE Publishing, all rights reserved. Figure 3. Heat-transfer model of a pavement and its surrounding environment 229 Transport Volume 174 Issue 4 A mechanistic approach to predict built-in temperature in concrete pavements Sok and Lee where Cc is the cementitious materials content (kg/m3) and the other parameters are defined in the notation list. Hu is the total heat of hydration of cementitious materials at 100% hydration (J/kg), which can be calculated by where qabs is solar absorption of concrete (W/m2), qir is the thermal irradiation from the surface (W/m2), qconv is the heat convection transfer (W/m2), q is the heat generation rate of cement hydration (determined by Equation 2), δsurface is the (differential) pavement thickness for the energy balance and Ts is the surface pavement temperature (°C). 3: Hu ¼ Hcem pcem þ 461pslag þ 1800pFACaO pFA Hcem ¼ 500pC3 S þ 260pC2 S þ 866pC3 A þ 420pC4 AF þ 624pSO3 4: þ 1186pFreeCaO þ 850pMgO The degree of hydration α(te) and the ultimate degree of hydration αu can be defined based on the mathematical model developed by Schindler and Folliard (2005), given by 5: 6: β ! τ αðte Þ ¼ αu exp te αu ¼ 1031 w=c þ 05pFA þ 03pslag 1 0194 þ w=c where 7: 8: 0401 0804 0758 τ ¼ 66 78p0154 FB pSO3 C3 A pC3 S 0227 0535 0558 pSO3 expð0647pslag Þ β ¼ 1814p0146 C3 A pC3 S FB te ðTr Þ ¼ t X 0 E 1 1 exp R 273 þ Tr 273 þ Tc All the parameters in these equations are defined in the notation list. 2.3 Boundary conditions The thermal balance equation at the pavement surface contains the foregoing heat flux through convection, radiation, absorption and conduction within the pavement surface and the pavement layers beneath, and the energy stored at the pavement surface. The thermal balance equation used in this study is expressed by (Gui et al., 2007) 10: 230 11: qconv ¼ hconv ðTa Ts Þ where Ta is the air temperature (°C), Ts is the surface temperature (°C) and hconv is the heat convection transfer coefficient (W/m2/°C), which can be determined as (Ashrae, 1993; TTG, 2009) 12: hconv ¼ 3727C½09ðTs þ Ta Þ þ 320181 pffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi ðTs Ta Þ0266 1 þ 2857vwind where vwind is the wind speed (m/s) and C is a constant correction factor depending on the heat flow condition. C is chosen as 1·79 when the pavement surface is warmer than the air and 0·89 when the pavement surface is cooler than the air. expð2187pslag þ 950pFA pFACaO Þ and the equivalent age te is given by 9: Convection is heat transfer by the mass of a gas or fluid motion, such as air or water, when the heated gas or fluid is made to move away from the source of heat, carrying energy with it. Generally, Newton’s law of cooling is used to express heat convection at the surface (Ashrae, 1993) qabs þ qir þ qconv þ qδsurface þ kc @T @x @Ts ¼ δsurface ρc cc @t surface Downloaded by [] on [24/10/22]. Copyright © ICE Publishing, all rights reserved. Solar radiation is the most important source of heat to pavement structures. Solar radiation propagates energy as a short wave arriving at the ground surface. The amount of energy absorbed by a pavement’s surface depends on the medium’s thermal properties and the colour of the pavement surface. McCullough and Rasmussen (1999) express the heat flux absorbed by a pavement surface as 13: qabs ¼ γabs If qsolar where γabs is the solar absorptivity of the concrete, which can be 0·1–0·35 for a pavement with a white curing compound, qsolar is the peak solar radiation during a daytime period and If is an intensity factor, which depends strongly on the atmospheric conditions, diurnal cycle, latitude and the incident angle between the sun’s rays and the pavement surface. It is assumed to follow a sinusoidal function that ranges from zero at sunrise and sunset to a peak value at the solar noon (McCullough and Rasmussen, 1999). Thermal irradiation is a long-wave heat transfer between the ground and the sky. It depends on ground cover conditions such as vegetation cover, the pavement surface and so on. The Stefan–Boltzmann law is commonly used for this type of heat Transport Volume 174 Issue 4 A mechanistic approach to predict built-in temperature in concrete pavements Sok and Lee transfer, which is defined by (McAdams, 1954) weather station for the previous 3 d are used as input values to calculate the temperature profiles. The temperature distribution within the substructure at the end of 3 d is then obtained. This temperature is adopted as the initial temperature distribution in the underlying layer for prediction of the subsequent concrete pavement temperature. 14: 4 Ts4 Þ qir ¼ εp σðTsky where εp is the surface emissivity, which depends on the pavement’s surface colour (for a perfectly black surface εp = 1), σ is the Stefan–Boltzmann constant (5·669 10−8 W/m−2.K−4) and Tsky is the effective sky temperature (K ), which is not equal to the ambient temperature but is a function of the dew point temperature and cloud cover. Based on the model proposed by Walton (1983), it is expressed as 15: Tsky ¼ ε025 sky Ta 16: εsky ¼ 0787 þ 0764 ln Tdp þ 273 Fcloud 273 2.5 Concrete final setting time The final setting time of concrete denotes the time at which fresh concrete begins to gain the mechanical properties and thus to carry stresses. Based on ASTM C 403 (ASTM, 2008), the final setting time of concrete is defined in terms of a penetration resistance of 27·6 MPa. According to Schindler et al. (2002), for any particular mixture design, the setting of concrete occurs at a certain degree of hydration. Schindler et al. (2002) proposed that the critical degree of hydration (αcr) at the final setting time of a particular mixture can be correlated with water/cementitious material (w/c) ratio, expressed as 19: 17: Fcloud ¼ 10 þ 0024N 00035N 2 þ 000028N 3 where Ta is the air temperature (K), εsky is sky emissivity, N is cloud cover with a value from 0 to 1, Tdp is the local dew point temperature (°C) and Fcloud is the cloud cover factor. αcr ¼ ks ðw=cÞ where ks is a constant value, equal to 0·26. In this study, the final setting time of a concrete slab was assumed to occur when the calculated degree of hydration at the mid-depth of the slab as presented in Equation 5 reaches the critical degree of hydration (αcr) as given by Equation 19. 2.6 2.4 Initial pavement condition The concrete placement temperature can initially be determined based on the temperature of the concrete ingredients. The contribution of each constituent is calculated from its temperature, specific heat and weight fraction. According to Mindess et al. (2003), the concrete placement temperature (Tconcrete) can be calculated by 18: Tconcrete 022ðTagg Wa þ Tcem Wc Þ þ Tagg Wwa þ Tw Ww ¼ 022ðWa þ Wc Þ þ Wwa þ Ww where Tagg, Tcem and Tw are the temperatures of aggregate, cement and water, respectively and Wa, Ww, Wc and Wwa are the weights of dry aggregate, water, cement and wet aggregate, respectively. For this study, an assumption for the temperature at the bottom of the subgrade layer is made. At a ground depth greater than 5 m, the ground temperature is at a constant value of 12°C (Williams and Gold, 1976). The temperature model enables prediction of the initial temperature distribution of the sub-base layer before concrete placement as follows. Firstly, the temperature distribution in the sub-base layer is assumed to be linear. The temperature of the upper layer of the sub-base is assumed to be the mean monthly air temperature while the temperature of the lower layer is the ground temperature (Ren, 2015). Then, climate data from the nearest Downloaded by [] on [24/10/22]. Copyright © ICE Publishing, all rights reserved. Numerical implementation of the temperature model Incorporating known boundary and initial conditions, Equation 1 can be solved using the 1D finite-difference method. The unsteady unit ∂T/∂t and ∂T/∂x are applied in a forward difference scheme while ∂ 2T/∂x 2 adopts the central difference scheme, giving 20: k k 2Tik þ Ti1 @ 2 T Tiþ1 ¼ 2 2 @x Δx 21: @T Tikþ1 Tik ¼ @t Δt 22: k Tik @T Tiþ1 ¼ @x Δx For the boundary condition at the pavement surface (x = 0) and assuming δsurface = Δxc/2; introducing Equations 21 and 22 into Equation 10 yields 23: T0kþ1 ¼ T0k þ 2 qk Δt qk Δt kc Δt k T T0k þ 0 þ 2 st ρc cc Δxc ρc cc ρc cc Δx2c 1 231 Transport Volume 174 Issue 4 A mechanistic approach to predict built-in temperature in concrete pavements Sok and Lee where i and k are the node and time step, respectively, and cc, kc, ρc and Δxc are the heat capacity, thermal conductivity, density and space increment of the concrete layer, respectively. qkst is calculated by summing qkabs, qkir and qkconv at time step k. qk0 is the internal heat of cement hydration rate at time step k. For fresh concrete, the thermal conductivity kc and the specific heat of concrete change with respect to the degree of hydration. The empirical equations to calculate these parameters with respect to the degree of hydration can be found elsewhere (Ruiz et al., 2001; Van Breugel, 1991). The proposed numerical solution of the heat-transfer problem in a pavement structure can easily be implemented in either a high-level programming language or a spreadsheet. In this study, prediction of temperature was programmed in Matlab. For an interior node within the pavement layer, the following finite-differential expression can be determined by introducing Equations 20 and 21 into Equation 1. Tk+1 of the interior i nodes within the pavement layer is explicitly calculated according to the known previous temperature data 24: Tikþ1 ¼ Tik þ qki Δt kc Δt k k 2 Tiþ1 2Tik þ Ti1 þ ρc cc ρc cc Δxc In the multi-layered interface between a pavement and it subbase, as well as between the sub-base and the ground, the continuity of heat must be maintained and Tk+1 of the interface i nodes within the pavement layer is given by Tikþ1 ¼ Tik þ 2 25: þ2 þ λa Δt T k Tik ðρa ca Δxa þ ρb cb Δxb Þ Δxa i1 λb Δt T k Tik ðρa ca Δxa þ ρb cb Δxb Þ Δxb iþ1 ΔtΔxa qk ðρa ca Δxa þ ρb cb Δxb Þ a in which ca, λa, ρa and Δxa are the heat capacity, thermal conductivity, density and space increment of the upper layer, respectively, while cb, λb, ρb and Δxb are the heat capacity, thermal conductivity, density and space increment of the underlying layer. qka is the heat of cement hydration at the interface of the upper and underlying layer when the upper layer consists of hardening concrete layer, otherwise qka is equal to zero (Ren, 2015). The temperature of the bottom node of the subgrade is assumed to be a constant value equal to the ground temperature, as mentioned Section 2.4. Thus 26: kþ1 TMðx5 mÞ ¼ constant 3. Validation of the BITD 3.1 Summary of field test section A concrete paving project constructed in the Sokcho region of South Korea on 28 April 2016 was monitored to determine the temperature distribution in hardening concrete and the magnitude of the BITD. The pavement, constructed using rollercompacted concrete (RCC), is 400 m long and 5 m wide, with a slab thickness of 0·2 m. The concrete slab was placed on a compacted granular base, also 0·2 m thick. The mixture design and the RCC material properties are summarised in Table 1. Air temperature data during construction were obtained from weather centre reported results; the maximum and minimum air temperatures were about 12°C and 7°C, respectively. The wind speed ranged from 0 to 2 m/s, with an average value of about 1 m/s. Concrete placement began at 10 a.m. and the monitored concrete slab section was placed at around 2 p.m. An appropriate amount of curing compound was immediately sprayed on the top surface of the concrete slab. To measure the deformation and temperature of the concrete slab, vibrating wire strain gauges (VWSGs) (model KM-100B) and thermocouple sensors (iButtons) were installed during concrete placement, as shown in Figure 4. The concrete slab was instrumented with iButton sensors at different depths of the concrete slab (50 mm, 100 mm and 150 mm below the pavement surface). Since temperature measurements were taken at only three points over the depth of the pavement, a second-degree polynomial was used to find the temperature distribution in the overall depth of the slab, along with the temperatures at the top and bottom of the slab. The sensors were programmed to collect temperature data at 60 min intervals from the start of construction. 3.2 Validation of final set of the field concrete slab A comparison was made between the final set of the field concrete slab based on the mathematical formula given in Equation 5 and the practical method to determine the final Table 1. Mix proportions and material properties of the RCC at the study site Parameter To ensure stability of the model, an important limitation of the explicit numerical integration scheme is considered. For 1D schematisation with time integration, the following criterion holds. 27: 232 λ Δt 1 ρc Δx2 2 Downloaded by [] on [24/10/22]. Copyright © ICE Publishing, all rights reserved. Cement type I: kg/m3 Fine aggregate: kg/m3 Coarse aggregate: kg/m3 Water: kg/m3 28 d flexural strength: MPa 28 d elastic modulus: MPa Value 280 1032 1072 107 4·8 24 500 Transport Volume 174 Issue 4 20 cm A mechanistic approach to predict built-in temperature in concrete pavements Sok and Lee raw strain started to change to be opposite to the variation in concrete temperature about 6·1 h and 6·3 h after concrete placement for the two respective locations. The average of these two times was 6·2 h (372 min). This point was defined as the final setting time of the field concrete slab. The final setting time based on this method was slightly longer than that obtained from Equation 5. Since the final setting time based on this method was assumed to occur when the surrounding concrete and measured strain exhibited composite behaviour, the delayed final setting time might be contributed by a function of restraint of the concrete slab (e.g. friction base) as compared with the final setting time defined in ASTM C 403 (ASTM, 2008). 5 cm 5 cm 5 cm Concrete slab Granular base VWSG iButton (a) The final setting time determined by the strain–temperature relationship found in this study was slightly longer than the final setting time calculated based Equation 5 and it is believed that there was no significant effect on the built-in temperature distribution in the concrete slab. (b) Figure 4. Installation of VWSGs and temperature sensors: (a) positions of the sensors; (b) sensor installation setting time of concrete suggested by Glisic and Simon (2000). According to Equation 5, the final set of concrete occurs when the degree of hydration in the concrete reaches the critical degree of hydration given by Equation 19. In this study, the concrete mixture comprised 280 kg/m3 Portland cement type I with a w/c ratio of 0·38 (Table 1). For the Portland cement type I, pC3S, pC2S, pC3A, pSO3 and FB were 0·55, 0·18, 0·1, 0·026 and 365 m2/kg, respectively. Fly ash and slag were not used in the mixture. Table 2 shows the calculated values of the hydration parameters based on Equations 5–8 and Equation 19. Based on the work of Glisic and Simon (2000), the final setting time of concrete in the field was assumed to occur when the VWSGs and the surrounding concrete exhibited composite behaviour based on monitored raw VWSG readings. Figure 5 shows the raw strain readings and concrete temperature developed in the concrete slab 50 mm and 150 mm below the concrete surface. As shown in the figure, the measured 3.3 Validation of temperature prediction The developed numerical model for predicting the temperature throughout a concrete slab at early age (72 h after concrete placement) was validated with field-measured temperature data. Table 3 lists the thermal properties of the pavement materials used in the validation (FHWA, 2006). To ensure stability of the numerical solution, the input time step in this analysis was 180 s and the input space increments were 2 cm for the concrete layer, 2 cm for the granular base layer and 10 cm for subgrade soil layer. Figure 6 shows the predicted and measured temperature difference between the top and bottom of the concrete slab. As shown in the figure, the temperature difference predicted using the developed model agreed well with the field-measured data. The slight difference between the predicted and measured results may be due to the different depths of the thermocouple sensors in the field and the numerical input depth and also to the inaccuracy of using a second-degree polynomial to find the temperature at the top and bottom of the slab. However, overall, the agreement was good, with a maximum discrepancy of about 2°C. Figure 6 also shows that the measured BITD (the temperature difference between the top and bottom of the slab at the setting time) (−0·4°C) agreed quite well with the predicted value (−0·1°C). Therefore, the developed numerical model can be used to establish the BITD under different conditions. Table 2. Analysis results of degree of hydration Parameter Hydration time parameter, τ Hydration shape parameter, β Ultimate degree of hydration, αu Critical degree of hydration, αcr Final setting time: min Value 16·75 0·63 0·69 0·099 330 Downloaded by [] on [24/10/22]. Copyright © ICE Publishing, all rights reserved. 4. Sensitivity analysis of BITD 4.1 Input parameters Many factors can affect the built-in temperature distribution in a concrete pavement. The effect of climatic conditions, concrete placement time and cementitious materials on the built-in temperature were investigated using the developed 233 Transport Volume 174 Issue 4 A mechanistic approach to predict built-in temperature in concrete pavements Sok and Lee 40 –1250 35 –1290 30 –1310 25 –1330 20 –1350 15 –1370 10 Concrete temperature: °C Estimated setting time –1270 Raw strain: mm/mm Raw strain Concrete temperature 5 –1390 0 6 12 18 24 30 36 42 48 Time after concrete placement: h (a) 390 Estimated setting time Raw strain: mm/mm 380 30 370 25 360 20 350 15 340 Concrete temperature: °C 35 Raw strain Concrete temperature 10 330 5 320 0 6 12 18 24 30 36 42 48 Time after concrete placement: h (b) Figure 5. Determination of concrete setting time: (a) 50 mm below surface; (b) 150 mm below surface Table 3. Thermal properties of pavement materials Property Concrete Density: kg/m3 Specific heat: J/kg.°C Conductivity: W/m.°C Coefficient of solar absorption Emissivity Density: kg/m3 Specific heat: J/kg.°C Conductivity: W/m.°C Density: kg/m3 Specific heat: J/kg.°C Conductivity: W/m.°C Granular base Subgrade Value 2350 1000 3 0·35 0·85 1898 1047 2·42 1850 1200 1·5 Temperature difference: °C Pavement material 14 12 Measured Predicted Estimated setting time 10 8 6 4 2 0 –2 –4 0 12 24 36 48 60 72 Time after concrete placement: h Figure 6. Predicted and measured temperature gradients in the concrete slab numerical model. Table 4 summarises the climate data for two seasons in South Korea. For the concrete pavement, the thickness of the concrete layer was assumed to be 0·2–0·4 m, the granular layer was assumed to be 0·2 m thick and the 234 Downloaded by [] on [24/10/22]. Copyright © ICE Publishing, all rights reserved. subgrade soil thickness was taken as 5 m. The thermal properties of these materials were as shown in Table 3. Pavement placing times were assumed to be 10 a.m., 2 p.m. and 6 p.m., A mechanistic approach to predict built-in temperature in concrete pavements Sok and Lee Transport Volume 174 Issue 4 Table 4. Average climate data for two seasons in South Korea Season Low temperature: °C High temperature: °C Solar radiation: W/m2 Relative humidity: % Wind speed: m/s Autumn Summer 4 22 12 31 500 700 65 75 3 1·5 which are typical times for concrete placement in South Korea. To investigate the effects of the concrete mix proportions on the BITD, two types of concrete mixtures were considered: ordinary Portland cement concrete (OPCC) (330 kg/m3) and OPCC with 20% fly ash and 20% slag. 4.2 Effect of concrete placement time Figure 7 shows the effects of concrete placement time on the magnitude of the BITD in the concrete slab for both autumn and summer construction for the OPCC mix and a pavement thickness of 30 cm. As shown in Figure 7(a), the distributions of built-in temperature in the concrete slab exhibited nonlinearity for all concrete placement times in both seasons. The assumption of a linear BITD during calculations of Temperature distribution at final set: °C 5 15 25 35 45 Pavement depth: cm 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 Autumn construction (10 a.m.) Autumn construction (2 p.m.) Autumn construction (6 p.m.) Summer construction (10 a.m.) Summer construction (2 p.m.) Summer construction (6 p.m.) thermal stress and deformation would thus lead to inaccurate results and therefore it is essential to consider the non-linearity in the built-in temperature distribution along a slab when calculating its thermal stress and deformation. Figure 7(b) shows the magnitude of the BITD for different concrete placement times. For construction in the summer, a large positive built-in temperature gradient was observed for concrete placed at 10 a.m. This large positive BITD was expected for concrete placed in the morning of a hot summer day since the top surface of the concrete slab would be directly exposed to solar radiation plus the additional heat of hydration. This would lead to the slab curling upwards when the temperature difference between the top and bottom of the slab falls below this BITD at a later age. The BITD magnitudes decreased and were mostly changed from positive to negative when the concrete placement times were changed to afternoons (2 p.m. and 6 p.m.). A late-afternoon paving (6 p.m.) would reach the final setting time during the night and therefore the BITD could be negative. A concrete slab constructed during the late afternoon of a summer day will thus curl permanently downwards if the temperature difference between the top and bottom of the slab at a later age is zero. For Autumn construction, a positive BITD of relatively small magnitude was observed when the concrete placement time was at 10 a.m. However, concrete placed during the afternoon (2 p.m.) and late afternoon (6 p.m.) exhibited a negative BITD since the final setting time of the concrete slab would occur at a cooler time of the day. Overall, concrete pavements placed in the autumn were found to exhibit smaller BITD magnitudes than pavements constructed in the summer months. (a) 12 Autumn construction Summer construction 10 7·25 8 BITD: °C 6 3·31 4 2 1·16 0 –2 –1·53 –4 –2·16 –4·23 –6 10 a.m. 2 p.m. 6 p.m. Concrete placement time (b) Figure 7. Effect of concrete placement time on built-in temperature: (a) distribution; (b) magnitude Downloaded by [] on [24/10/22]. Copyright © ICE Publishing, all rights reserved. 4.3 Effect of concrete mix design Differences in the concrete mix proportions due to the addition of fly ash and slag changed the magnitude of the BITD. Figure 8 shows the effects of the concrete mix proportion on the magnitude of the BITD for a 30 cm concrete slab placed at different times on a typical summer day. As the addition of fly ash and slag can reduce the rate of heat hydration and therefore the concrete temperature, the final setting time of the concrete slab will be delayed. For the concrete pavement placed in the afternoon (2 p.m.) and late afternoon (6 p.m.) of a summer day, the BITDs of the concrete slab made with fly ash and slag were lower than those of the pavement made with only OPCC. The results showed that the final setting time of concrete placed at 2 p.m. occurred in the early evening, and produced a small positive BITD for the OPCC. Therefore, adding fly ash and slag significantly delayed the final setting 235 Transport Volume 174 Issue 4 A mechanistic approach to predict built-in temperature in concrete pavements Sok and Lee 12 10 8 OPCC OPCC + 20% fly ash + 20% slag 8·50 7·25 BITD: °C 6 3·31 4 1·51 2 0 –2 –4 –6 –4·23 10 a.m. 2 p.m. –3·75 6 p.m. Concrete placement time Figure 8. Effect of cementitious material on BITD for summer construction time of concrete to the evening, thus reducing the BITD. Similarly, for concrete placed at 6 p.m., the final setting time occurred in the night, producing a large negative BITD for the OPCC pavement. However, with fly ash and slag added to the concrete mixture, the final setting time would be delayed until the early morning, thus resulting in a smaller negative 12 Autumn construction Summer construction 10 BITD: °C 8 7·52 7·25 6·81 6 4 1·92 2 1·16 0·51 0 20 30 40 BITD compared with that of the OPCC pavement. In contrast to concrete placement during the afternoon (2 p.m.) and late afternoon (6 p.m.), concrete placement in the morning of a summer day led to a larger BITD for the concrete with fly ash and slag. The results indicate that, for morning placement, the final setting time of the OPCC occurred in the early afternoon, but did not coincide with the peak solar radiation during the day. The addition of fly ash and slag delays the final setting time of concrete significantly, thus leading to a final setting time coinciding with peak solar radiation and thus generating a large positive BITD. In summary, adding fly ash and slag to the concrete mixture has a significant effect on the magnitude of BITD, increasing or decreasing the BITD depending on the concrete placement time. 4.4 Effect of pavement thickness The effects of concrete slab thickness on the BITD were also investigated. The proposed model was used to establish the BITD for OPCC slab thicknesses ranging from 20 cm to 40 cm for both autumn and summer constructions. The concrete placement time was selected to be 10 a.m. Figure 9 shows that when the slab thickness was increased, the BITD slightly increased for both autumn and summer placements. 4.5 Summary Table 5 summarises the BITDs of the concrete slab (OPCC mix design) for different construction seasons, concrete placement times and slab thicknesses. The slab thickness had little effect on the BITD, with differences of only about 1·5°C. The BITD was very similar for slab thicknesses of 30 cm and 40 cm. In contrast, the concrete placement time and construction season had significant effects on both the magnitude and sign of the BITD. With a change in concrete placement time from morning to afternoon or early evening, the BITD decreased and mostly changed from a positive to a negative value for both autumn and summer construction. Slab thickness: cm Figure 9. Effect of pavement thickness on BITD for autumn and summer construction 5. Conclusions A mechanistic approach to predicting the built-in temperature gradient of a concrete pavement slab has been suggested. Table 5. BITDs of OPCC concrete slab under different conditions BITD: °C Summer placement Slab thickness: cm 20 30 40 236 Autumn placement 10 a.m. 2 p.m. 6 p.m. 10 a.m. 2 p.m. 6 p.m. 6·81 7·25 7·52 3·59 3·31 3·25 −3·09 −4·23 −4·54 0·51 1·16 1·92 −1·52 −1·53 −1·63 −1·57 −2·16 −2·58 Downloaded by [] on [24/10/22]. Copyright © ICE Publishing, all rights reserved. Transport Volume 174 Issue 4 A mechanistic approach to predict built-in temperature in concrete pavements Sok and Lee The numerical model to predict the temperature distribution in a hardening concrete slab was developed using the finite-difference method. A mathematical formula to predict the final setting time based on the concrete degree of hydration was integrated in the temperature predictive model to establish the BITD. The BITD results from the proposed method showed good agreement with field-measured data. Using the developed numerical model, the effects of climatic conditions, concrete mix design, concrete placement time and pavement thickness on the BITD were also investigated. The modelling results indicated that climatic conditions have sustainable effects on the BITD. A concrete slab constructed during the summer was found to have large positive or negative BITD, whereas smaller BITDs (again positive or negative) were obtained for concrete placed during the autumn. Concrete placement time during the day was also found to have a significant effect on the BITD. In hot weather conditions (summer), changing the placement time from morning to late afternoon changed the BITD from a large positive value to a small negative one. The addition of fly ash and slag to the concrete mix was found to decrease or increase the magnitude of the BITD depending on the concrete placement time during the day. The pavement thickness was found to have little effect on the BITD. Glisic B and Simon N (2000) Monitoring of concrete at very early age In summary, the model proposed in this paper can be used to predict the BITD in concrete slabs for a given concrete mix design, concrete placement time, pavement thickness and environmental condition. Acknowledgements This study was supported by Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT) and the Korea Agency for Infrastructure Technology Advancement (KAIA): grant number [18TLRP-B146707-01], and the 2017 Academic Research Program funded by Gangneung-Wonju National University. REFERENCES ARA (2002) Mechanistic–Empirical Pavement Design Guide. Part 3: Design and Analysis. ERES Consultants Division, Applied Research Associates, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA. Ashrae (American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers) (1993) ASHRAE Handbook: Fundamentals. ASHRAE, Atlanta, GA, USA. ASTM (2008) C 403: Standard test method for time of setting of concrete mixtures by penetration resistance. ASTM International, West Conshohocken, PA, USA. Coree B (2005) Implementing the Mechanistic–Empirical Pavement Design Guide. Iowa State University, Ames, IA, USA. Report prepared for the Iowa Highway Research Board (IHRB), Project TR-509. FHWA (Federal Highway Administration) (2006) Appendix B: Models Selected for Incorporation Into HIPERPAV II. FHWA, Washington, DC, USA. See https://www.fhwa.dot.gov/ publications/research/infrastructure/pavements/pccp/04127/ appb.cfm (accessed 152/08/2018). Downloaded by [] on [24/10/22]. Copyright © ICE Publishing, all rights reserved. using stiff SOFO sensor. Cement & Concrete Composites 22(2): 115–119. Gui J, Phelan PE, Kaloush KE and Golden JS (2007) Impact of pavement thermophysical properties on surface temperatures. Journal of Materials in Civil Engineering 19(8): 683. Hall KD and Beam S (2004) Estimating the sensitivity of design input variables for rigid pavement analysis with Mechanistic–Empirical Design Guide. Transportation Research Record 1919: 65–73. Hansen W, Wei Y, Smiley DL, Peng Y and Jensen EA (2006) Effects of paving conditions on built-in curling and pavement performance. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 7(4): 291–296. Kannekanti V and Harvey J (2005) Sensitivity Analysis of 2002 Design Guide Rigid Pavement Distress Prediction Models. University of California, Davis, CA, USA, Report prepared for the California Department of Transportation. McAdams W (1954) Heat Transmission. McGraw Hill, New York, NY, USA. McCullough BF and Rasmussen RO (1999) Fast Track Paving: Concrete Temperature Control and Traffic Opening Criteria for Bonded Concrete Overlays, Task, G, Vol 1. US Department of Transportation, Washington, DC, USA, FHWA-RD-98-167. Mindess S, Young JF and Darwin D (2003) Mineral admixtures and blended cements. In Concrete, 2nd edn. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, pp. 93–114. Narasimhan TN (1999) Fourier’s heat conduction equation: history, influence, and connections. Reviews of Geophysics 37(1): 151–172. Nassiri S and Vandenbossche M (2012) Establishing built-in temperature gradient for jointed plain concrete pavements in Pennsylvania. International Journal of Pavement Research and Technology 5(4): 245–256. Rao C, Barenberg EJ, Snyder MB and Schmidt S (2001) Effect of temperature and moisture on the response of jointed concrete pavements. In 7th International Conference on Concrete Pavements: The Use of Concrete in Developing Long-Lasting Pavement Solutions for the 21st Century. International Society for Concrete Pavements, Orlando, FL, USA, vol. 1, pp. 23–28. Ren D (2015) Optimisation of the Crack Pattern in Continously Reinforced Concrete Pavements. PhD thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, the Netherlands. Ruiz JM, Schindler AK, Rasmussen RO, Nelson PK and Chang GK (2001) Concrete temperature modeling and strength prediction using maturity concepts in the FHWA HIPERPAV software. In 7th International Conference on Concrete Pavements: The Use of Concrete in Developing Long-Lasting Pavement Solutions for the 21st Century. International Society for Concrete Pavements, Orlando, FL, USA, vol. 1, pp. 97–111. Schindler AK and Folliard KJ (2005) Heat of hydration models for cementitious materials. ACI Materials Journal 102(1): 24–33. Schindler AK, Dossey T and McCullough BF (2002) Temperature Control During Construction to Improve the Long Term Performance of Portland Cement Concrete Pavements. Center for Transportation Research, Austin, TX, USA. TTG (The Transtec Group) (2009) HIPERPAV: High Performance Concrete Paving Software. TTG, Austin, TX, USA. Van Breugel K (1991) Simulation of Hydration and Formation of Structure in Hardening Cement-Based Materials. PhD thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, the Netherlands. Walton GN (1983) Thermal Analysis Research Program Reference Manual. National Bureau of Standard, US Department of Commerce, Washington, DC, USA. Wells SA, Phillips BM and Vandenbossche JM (2006) Quantifying built-in construction gradient and early-age slab deformation caused by environmental loads in a jointed plain concrete 237 Transport Volume 174 Issue 4 A mechanistic approach to predict built-in temperature in concrete pavements Sok and Lee pavement. International Journal of Pavement Engineering 7(4): 275–289. Westergaard HM (1926) Analysis of stresses in concrete pavement due to variation of temperature. In Proceedings of the Sixth Annual Meeting of the Highway Research Board. Highway Research Borad, Washington, DC, USA, vol. 6, pp. 201–215. Williams GP and Gold LW (1976) Ground Temperatures. National Research Council of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, Canadian Building Digest 180. Yu HT and Khazanovich L (2001) Effects of construction curling on concrete pavement behavior. In 7th International Conference on Concrete Pavements: The Use of Concrete in Developing Long-Lasting Pavement Solutions for the 21st Century. International Society for Concrete Pavements, Orlando, FL, USA, vol. 1, pp. 55–67. Yu HT, Khazanovich L, Darter MI and Aridani A (1998) Analysis of concrete pavement responses to temperature and wheel loads measured from instrumented slabs. Transportation Research Record 1639: 94–101. How can you contribute? To discuss this paper, please email up to 500 words to the editor at journals@ice.org.uk. Your contribution will be forwarded to the author(s) for a reply and, if considered appropriate by the editorial board, it will be published as discussion in a future issue of the journal. Proceedings journals rely entirely on contributions from the civil engineering profession (and allied disciplines). Information about how to submit your paper online is available at www.icevirtuallibrary.com/page/authors, where you will also find detailed author guidelines. 238 Downloaded by [] on [24/10/22]. Copyright © ICE Publishing, all rights reserved.