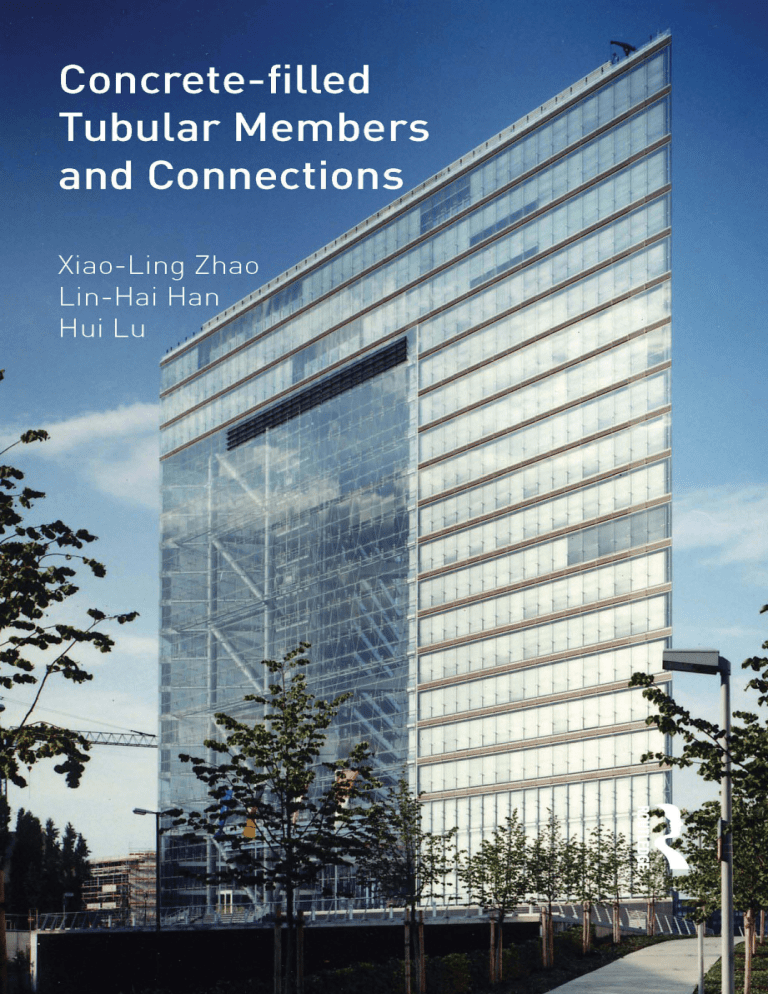

Xiao Ling Zhao Lin Hai Han Hui Lu Concrete filled Tubular Members

Anuncio

Concrete-filled Tubular

Members and Connections

Concrete-filled Tubular

Members and Connections

Xiao-Ling Zhao, Lin-Hai Han and Hui Lu

First published 2010

by Spon Press

This edition published 2013 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 1001786$

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

© 2010 Xiao-Ling Zhao, Lin-Hai Han and Hui Lu

Publisher’s note

This book has been prepared from a camera-ready copy supplied by the authors

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any

electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and

recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the

publishers.

This publication presents material of a broad scope and applicability. Despite stringent efforts by all

concerned in the publishing process, some typographical or editorial errors may occur, and readers are

encouraged to bring these to our attention where they represent errors of substance. The publisher and author

disclaim any liability, in whole or in part, arising from information contained in this publication. The reader

is urged to consult with an appropriate licensed professional prior to taking any action or making any

interpretation that is within the realm of a licensed professional practice.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Zhao, Xiao-Ling.

Concrete-filled tubular members and connections / Xiao-Ling Zhao, Lin-Hai Han, and Hui Lu.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Columns, Concrete. 2. Concrete-filled tubes. 3. Concrete-filled tubes--Joints. I. Han, Lin-Hai. II. Lu, Hui,

1963- III. Title.

TA683.5.C7Z48 2010

624.1'83425--dc22

2009053651

ISBN13: 978-0-415-43500-0 (hbk)

ISBN13: 978-0-203-84834-0 (ebk)

Table of Contents

Preface

ix

Notation

xi

Chapter 1: Introduction …………………………………………………………

1.1 Applications of Concrete-Filled Steel Tubes ………………………………

1.2 Advantages of Concrete-Filled Steel Tubes ………………………………..

1.3 Current Knowledge on CFST Structures …………………………………...

1.3.1 Related Publications………………………………………………...

1.3.2 International Standards …………………………………………….

1.4 Layout of the Book …………………………………………………………

1.5 References ………………………………………………………………….

1

1

10

13

13

14

14

15

Chapter 2: Material Properties and Limit States Design ……………………...

2.1 Material Properties …………………………………………………………

2.1.1 Steel Tubes …………………………………………………………

2.1.2 Concrete ……………………………………………………………

2.2 Limit States Design ………………………………………………………...

2.2.1 Ultimate Strength Limit State ……………………………………...

2.2.2 Serviceability Limit State …………………………………………..

2.3 References ………………………………………………………………….

19

19

19

24

26

26

28

29

Chapter 3: CFST Members Subjected to Bending …………………………….

3.1 Introduction ………………………………………………………………...

3.2 Local Buckling and Section Capacity ……………………………………...

3.2.1 Local Buckling and Classification of Cross-Sections ……………...

3.2.2 Stress Distribution ………………………………………………….

3.2.3 Derivation of Plastic Moment Capacity ……………………………

3.2.4 Design Rules for Strength ………………………………………….

3.2.5 Comparison of Specifications ……………………………………...

3.2.6 Examples …………………………………………………………...

3.3 Member Capacity …………………………………………………………..

3.3.1 Flexural-Torsional Buckling ……………………………………….

3.3.2 Effect of Concrete-Filling on Flexural-Torsional Buckling

Capacity ……………………………………………………………

3.4 References ………………………………………………………………….

31

31

32

32

33

33

40

45

46

58

58

59

61

vi

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

Chapter 4: CFST Members Subjected to Compression ………………………

4.1 General ……………………………………………………………………..

4.2 Section Capacity ……………………………………………………………

4.2.1 Local Buckling in Compression ……………………………………

4.2.2 Confinement of Concrete …………………………………………..

4.2.3 Design Section Capacity …………………………………………...

4.2.4 Examples ……………………………………………………….......

4.3 Member Capacity …………………………………………………………..

4.3.1 Interaction of Local and Overall Buckling ………………………...

4.3.2 Column Curves …………………………………………………….

4.3.3 Design Member Capacity ………………………………………….

4.3.4 Examples …………………………………………………………...

4.4 References ………………………………………………………………….

65

65

69

69

70

72

78

90

90

91

101

103

117

Chapter 5: CFST Members Subjected to Combined Actions …………………

5.1 General ……………………………………………………………………..

5.2 Stress Distribution in CFST Members Subjected to Combined Bending

and Compression …………………………………………………………...

5.3 Design Rules ………………………………………………………………..

5.3.1 BS5400-5:2005 …………………………………………………….

5.3.2 DBJ13-51 …………………………………………………………..

5.3.3 Eurocode 4 ………………………………………………………...

5.3.4 Comparison of Codes ………………………………………………

5.4 Examples …………………………………………………………………...

5.4.1 Example 1 CFST SHS ……………………………………………...

5.4.2 Example 2 CFST CHS ……………………………………………..

5.5 Combined Loads Involving Torsion or Shear ……………………………...

5.5.1 Compression and Torsion ………………………………………….

5.5.2 Bending and Torsion ……………………………………………….

5.5.3 Compression, Bending and Torsion ………………………………..

5.5.4 Compression, Bending and Shear ………………………………….

5.5.5 Compression, Bending, Torsion and Shear ………………………...

5.6 References ………………………………………………………………….

123

123

125

128

128

131

134

135

137

137

146

156

156

157

157

159

159

160

Chapter 6: Seismic Performance of CFST Members ………………………….

6.1 General ……………………………………………………………………..

6.2 Influence of Cyclic Loading on Strength …………………………………..

6.2.1 CFST Beams ……………………………………………………….

6.2.2 CFST Braces ……………………………………………………….

6.2.3 CFST Beam-Columns ……………………………………………...

6.3 Ductility …………………………………………………………………….

6.3.1 Ductility Ratio (ȝ) ………………………………………………….

163

163

166

166

168

168

168

168

Table of Contents

vii

6.3.2 Parameters Affecting the Ductility Ratio (ȝ) ………………………

6.3.3 Some Measures to Ensure Sufficient Ductility …………………….

Parameters Affecting Hysteretic Behaviour ………………………………..

6.4.1 Moment (M) versus Curvature (I) Responses …………………….

6.4.2 Lateral Load (P) versus Lateral Deflection (ǻ) Responses ………...

Simplified Hysteretic Models

6.5.1 Simplified Model of the Moment–Curvature Hysteretic

Relationship ......................................................................................

6.5.2 Simplified Model of the Load–Deflection Hysteretic

Relationship …………………………………………………….…

6.5.3 Simplified Model of the Ductility Ratio (ȝ) …………………..…...

References ………………………………………………………………….

184

185

Chapter 7: Fire Resistance of CFST Members ………………………………...

7.1 General ……………………………………………………………………..

7.2 Parameters Affecting Fire Resistance …………………………………….

7.3 Fire Resistance Design ……………………………………………………..

7.3.1 Chinese Code DBJ13-51 …………………………………………...

7.3.2 CIDECT Design Guide No. 4 ……………………………………

7.3.3 Eurocode 4 Part 1.2 ………………………………………………...

7.3.4 North American Approach …………………………………………

7.3.5 Comparison of Different Approaches ……………………………...

7.4 Examples …………………………………………………………………...

7.4.1 Column Design …………………………………………………….

7.4.2 Real Projects ……………………………………………………….

7.5 Post-Fire Performance ……………………………………………………...

7.6 Repairing After Exposure to Fire …………………………………………..

7.7 References ………………………………………………………………….

189

189

191

193

193

193

197

199

200

201

201

206

208

212

214

Chapter 8: CFST Connections …………………………………………………..

8.1 General ……………………………………………………………………..

8.2 Classification of Connections ………………………………………………

8.3 Typical CFST Connections ………………………………………………...

8.3.1 Simple Connections …………………………………………..........

8.3.2 Semi-Rigid Connections …………………………………………...

8.3.3 Rigid Connections ………………………………………………….

8.4 Design Rules ………………………………………………………………..

8.4.1 General ……………………………………………………………..

8.4.2 Design of Simple Connections ……………………………………..

8.4.3 Design of Rigid Connections ………………………………………

8.4.4 Bond Strength ……………………………………………………...

8.5 Examples …………………………………………………………………...

219

219

219

221

221

221

223

225

225

225

227

231

233

6.4

6.5

6.6

170

170

173

173

175

178

178

182

viii

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

8.5.1 Example 1 Simple Connection ……………………………………..

8.5.2 Example 2 Rigid Connection ………………………………………

More Recent CFST Connections …………………………………………...

8.6.1 Blind Bolt Connections …………………………………………….

8.6.2 Reduced Beam Section (RBS) Connections ……………………….

8.6.3 CFST Connections for Fatigue Application ………………………..

References ……………………………………………………………….....

233

236

239

239

239

240

241

Chapter 9: New Developments ………………………………………………….

9.1 Long-Term Load Effect …………………………………………………….

9.2 Some Construction-Related Issues …………………………………………

9.2.1 Effects of Local Compression ……………………………………...

9.2.2 Pre-Load Effect …………………………………………………….

9.3 SCC (Self-Consolidating Concrete)-Filled Tubes ………………………….

9.4 Concrete-Filled Double Skin Tubes ………………………………………..

9.4.1 General ……………………………………………………………..

9.4.2 CFDST Members Subjected to Static Loading …………………….

9.4.3 CFDST Members Subjected to Dynamic Loading ………………...

9.4.4 CFDST Members Subjected to Fire ……………………………….

9.5 FRP (Fibre Reinforced Polymer) Confined CFST …………………………

9.6 References ………………………………………………………………….

247

247

249

249

253

255

257

257

257

266

267

269

270

Index ………………………………………………………………………………

277

8.6

8.7

Preface

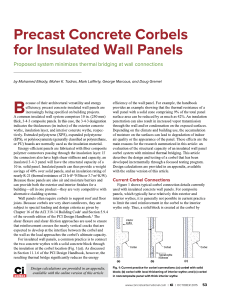

Concrete-filled steel tubes (CFSTs) have been used in many structural engineering

applications, such as columns in high-rise buildings and bridge piers. CFSTs can

be used in various fields ranging from civil and industrial construction through to

the mining industry.

A series of design guides on tubular structures have been produced by CIDECT

(International Committee for the Development and Study of Tubular Structures) to

assist practising engineers. The ones relevant to concrete-filled steel tubes are

CIDECT Design Guides No. 4, No. 5, No. 7 and No. 9. There are a few books

relevant to CFST members and connections. Some of the books are not focused on

concrete-filled steel tubes. For those which do, explanations of failure mechanism

and mechanics are not covered in detail. Most of the designs are based on

Eurocode 4. There is a lack of comparison of different design standards. Seismic

resistance has received only very little coverage. Worked examples are very

limited. This book will fill these gaps.

This book contains descriptions and explanation of some basic concepts. It not

only summarises the research performed to date on concrete-filled tubular

members and connections but also compares the design rules in various standards

(Eurocode 4, BS5400 Part 5, AS5100 Part 6 and Chinese Standard DBJ13-51), and

provides design examples. It also presents some recent developments in concretefilled tubular members and connections. It is suitable for structural engineers,

researchers and university students who are interested in composite tubular

structures.

Chapter 1 outlines the application and advantages of concrete-filled steel tubes

(CFSTs). Chapter 2 presents the material properties of steel tubes and concrete

given in various standards. The limit states design method is described. The

differences among the Australian, British, Chinese and European standards are

pointed out to help the readers to interpret the design comparison later in the book.

CFST members are covered in Chapter 3 (bending), Chapter 4 (compression) and

Chapter 5 (combined actions). Chapter 6 and Chapter 7 present the performance

and design methods of CFST structures under seismic loading and fire conditions.

Steel or RC beam to CFST column connection details and designing approaches

are covered in Chapter 8. Finally, Chapter 9 introduces some recent developments

on concrete-filled steel tubular structures, e.g. the effect of long-term loading on

the behaviour of CFST columns, the effect of axial local compression and preloads on the CFST column capacity, SCC (self-consolidating concrete)-filled

tubular members, concrete-filled double skin tubes (CFDST) and FRP (Fibre

Reinforced Polymer)-confined CFST columns. Comprehensive up-to-date

references are given in the book.

x

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

We appreciated the comments from Dr. Mohamed Elchalakani at Higher Colleges

of Technology, Dubai Mens College on Chapter 3, Dr. Ben Young at The

University of Hong Kong on Chapter 4, Dr. Leroy Gardner at Imperial College,

London, on Chapter 5, Prof. Amir Fam and Dr. Pedram Sadeghian at Queen’s

University, Canada, on Chapter 6, Prof. Yong-Chang Wang at The University of

Manchester on Chapter 7, Prof. Akihiko Kawano at Kyushu University on Chapter

8 and Dr. Zhong Tao at Fuzhou University on Chapter 9.

We would like to thank Prof. Dennis Lam at The University of Leeds, UK, for

providing necessary documents regarding BS5400 Part 5, Prof. Hanbin Ge at

Meijo University, Japan, for obtaining some relevant Japanese documents and Prof.

Peter Schaumann at The University of Hannover for discussions on fire design in

Eurocode 4. We are very grateful to Mr. Robert Alexander at Monash University

for preparing most of the diagrams and Ms. Dominique Thomson at Monash

University for checking the English. We wish to thank Thyssen Krupp Steel for

providing the front cover photo. We also wish to thank Simon Bates at Taylor &

Francis for his advice on the format of the book.

Finally, we wish to thank our families for their support and understanding during

the many years that we have been undertaking research on composite tubular

structures and during the preparation of this book.

Xiao-Ling Zhao, Lin-Hai Han and Hui Lu

January 2010

Notation

The following notation is used in this book. Where non-dimensional ratios are involved,

both the numerator and denominator are expressed in identical units. The dimensional

units for length and stress in all expressions or equations are to be taken as millimetres

and megapascals (N/mm2) respectively, unless specifically noted otherwise. When

more than one meaning is assigned to one symbol, the correct one will be evident from

the context in which it is used. Some symbols are not listed here because they are only

used in one section and well defined in the local context.

Aa

Ac

Aconcrete

Ac,nominal

Ag

Ainner

AL

Ant

Anv

Aouter

As

Asr

Asc

B

Bi

Bo

C

C1, C2 and C3

D

De

Di

Do

Ɯ

Ea

Ec

Ed

Es

elastic

E sc

G

Ia

Ib

Area of a steel hollow section defined in EC4

Area of concrete in CFST

Area of concrete in CFDST

Nominal cross-sectional area of concrete in CFDST

Gross cross-sectional area

Area of inner steel hollow section in CFDST

Localised load area on core concrete in CFST

Net area in tension for block failure

Net area in shear for block failure

Area of outer steel hollow section in CFDST

Area of steel in CFST

Area of steel reinforcement

Area of steel and concrete in CFST

Overall width of an RHS

Overall width of inner RHS in CFDST

Overall width of outer RHS in CFDST

Perimeter of CFST or carbonate aggregate

Compressive forces in Figure 3.3

Overall depth of an RHS

Outside diameter of a CHS in BS5400

Overall depth of inner RHS in CFDST

Overall depth of outer RHS in CFDST

Axial stiffness ratio of CFST

Modulus of elasticity for CHS defined in EC4

Modulus of elasticity of concrete

Design value of the effect of actions in EC4

Modulus of elasticity of steel

Section modulus of a composite section

Shear modulus of elasticity

Second moment of area of CHS

Second moment of area of beam

xii

Ic

Is

J

K

Ke

Kj,ini

K1

L

Lb

Le

Lp

Lw

M

Mc

MCFDST

Mmax

Mo

Mp

Ms

Mu,CFDST

Mux

Muy

Mx

My

Myu

N

Nb

Nc

NCFDST

Ncr

NE

No

Np

Ns

Nu

Nu,CFDST

Nu,L

Nu, nominal

Nup

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

Second moment of area of concrete

Second moment of area of steel hollow section

Torsion constant for a cross-section

Effective length factor

Flexural stiffness in the elastic stage of CFST

Initial rotation stiffness of connections

Member slenderness reduction factor given in Figure 4.6

Member length

Span of beam

Effective length of a member

Length of shear plate

Fillet weld length

Bending moment

Design moment at the beam end

Ultimate moment capacity of CFDST

Maximum moment for CFST under combined loads shown in Figure

5.1(d)

Elastic flexural-tensional buckling moment

Plastic moment capacity

Nominal section moment capacity

Section bending moment capacity of CFDST

Design ultimate moment of resistance of CFST about the major axis

Design ultimate moment of resistance of CFST about the minor axis

Bending moment about major principal x-axis

Bending moment about minor principal y-axis or yielding moment of

CFST

Ultimate moment of CFST under constant axial load

Axial force

Tensile force in an external diaphragm induced by the axial force in

beam

Design member capacity in compression

Section capacity of CFDST in compression

Critical buckling load of a compressive member

Elastic buckling load

Applied axial load on CFST

Pre-load on steel tube

Nominal section capacity of CFST

Design axial section capacity or squash load of CFST

Section capacity of CFDST in compression

Ultimate load of CFST subjected to long-term sustained load

Nominal axial capacity of CFST

Ultimate load of CFST with pre-load on steel tube

Notation

Nus

Nx

Nxy

Ny

N*

P

Py

Q

R

Rd

Ru

R*

S

S*

T

T1, T2

Tu

V

Vbolt

Vmax

Vu

Vweld

a

b

be

bf

bj

bs

d

db

di

din

xiii

Ultimate strength of unfilled steel tubular column

Design member capacity in compression under uniaxial bending

about the major axis restrained from failure about the minor axis

Design member capacity in compression under uniaxial bending

about the major axis unrestrained from failure about the minor axis or

under biaxial bending

Design member capacity in compression under uniaxial bending

about the minor axis, or yield capacity of external diaphragm

connections

Design axial tension load at beam end

Cyclic lateral load defined in Figure 6.3 or applied load in fire

Yield load of CFST or ultimate strength of CFST

Shear force at beam end

Ultimate resistance in DBJ13-51 or fire resistance

Design resistance in EC4

Nominal capacity

Design resistance

Design action effects in DBJ13-51 or siliceous aggregate, or plastic

section modulus of the steel section defined in BS5400

Design action effects

Torsion, or shear stress

Tensile forces in Figure 3.3

Torsion capacity of CFST

Shear force

Design shear capacity of a single bolt

Maximum shear force in beam web

Shear capacity of CFST

Design shear capacity per unit length of fillet weld

Thickness of fire protection for CFST

Clear width of an RHS or the least lateral dimension of a column

defined in BS5400 or effective width of diaphragm at critical section

Effective width of tube wall to resist tensile force in a diaphragm

connection

Overall width of an RHS defined in BS5400

Total length of weld defined in Figure 8.6

Flange width of steel I beam or overall depth or width of an RHS in

BS5400

Outside diameter of a CHS

Bolt diameter

Outside diameter of inner CHS in CFDST

Hole diameter of the inner diaphragm

xiv

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

d1

dn

Depth of web in steel I beam

Distance of neutral axis to interior surface of the compressive flange

of an RHS

Overall height of steel I beam

Load eccentricity

Design bond strength between steel and concrete in CFST

Ultimate strength of beam web

Bond strength between steel and concrete in CFST

Concrete compressive strength

Design cylinder strength of concrete defined in EC4

Standard compressive strength of concrete (Chapter 2), or

characteristic strength of concrete given in GB50010-2002 or

characteristic cylinder strength of concrete at 28 days given in EC4

Mean value of the compressive strength of concrete at the relevant

age

Characteristic compressive cube strength of concrete at 28 days

Ultimate strength of steel tube

Yield strength of steel tube

Characteristic compressive cylinder strength of concrete at 28 days

Ultimate strength of shear plate

Yield strength of shear plate

Ultimate strength of shear plate

Yield stress of steel diaphragm

Standard tensile strength of concrete

Tensile strength of concrete

Ultimate tensile strength of steel

Yield strength of beam web

Ultimate strength of beam web

Tensile yield stress of steel

Design yield strength of RHS defined in EC4

Overall depth of an RHS without a round corner defined in EC3, or

depth of concrete in BS5400 or overall depth of steel I beam

Fillet weld leg length

Distance defined in Figure 8.8

Reduction factor on concrete strength

Member effective length factor

Form factor

Strength factor under fire

Member length

Effective length of CFST

Length of a column for which Euler load equals the squash load

Load level or fire load ratio

doverall

e

fa

fb,w,u

fbond

fc

fcd

fck

fcm

fcu

fc,u

fc,y

fcc

fp,u

fp,y

fp,u

fs,y

ftk

ft

fu

fw,y

fw,u

fy

fyd

h

hf

hs

kc

ke

kf

kt

l

le

lE

n

Notation

xv

nb

pr

r

rc

rext

ri

rint

rm

t

tb,f

tb,w

tc

tf

ti

t1

tp

to

ts

Number of bolts

Percentage of reinforcement in CFST

Radius of gyration

Diameter of core concrete in CFST

External corner radius of an RHS

Inner radius of a CHS

Internal corner radius of an RHS

Middle radius between inner and outer surfaces of a CHS

Tube wall thickness or time

Thickness of flange of steel I beam

Thickness of web of steel I beam

Tube wall thickness

Wall thickness of an RHS defined in BS5400

Wall thickness of inner steel tube in CFDST

Thickness of diaphragm

Thickness of shear plate

Wall thickness of outer steel tube in CFDST

Thickness of steel beam flange

D

Steel ratio or angle between tensile force and critical section in

external diaphragm connection

Section constant of compression members

Concrete contribution factor defined in BS5400, or member

slenderness reduction factor defined in AS5100

Steel ratio

Depth-to-width ratio for RHS or local compression area ratio

Equivalent moment factor defined in GB50017

Ratio of smaller to larger bending moment at the ends of a member

about major axis

Ratio of smaller to larger bending moment at the ends of a member

about minor axis

Member slenderness reduction factor giver in Figure 4.9

Lateral deflection

Lateral displacement corresponding to Py as defined in Figure 6.1

Lateral displacement defined in Figure 6.1

Yield displacement defined in Figure 6.1

Deflection of structures or steel contribution ratio defined in EC4

Deflection limit of structures

Hogging of beams in the unloaded state

Variation of the deflection of beams due to the permanent loads

immediately after loading

Db

Dc

Ds

E

Em

Ex

Ey

Ȥ

ǻ

ǻp

ǻu

ǻy

į

įmax

įo

į1

xvi

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

į2

Variation of the deflection of beams due to the variable loading plus

the long-term deformation due to the permanent load

Shrinkage strain of core concrete in CFSTs

Resistance factor for yield of steel

Resistance factor for failure associated with a connector

Capacity factor or capacity factor for steel hollow section or

curvature

Capacity factor for concrete

Curvature corresponding to the yield moment

Slenderness reduction factor or stability factor

Material property factor of concrete

Coefficient of the building importance in DBJ13-51

Partial factor covering uncertainty in the resistance model plus

geometric deviation in EC4

Material property factor of steel

Curvature

Non-dimensional slenderness

Relative slenderness

Slenderness ratio of a steel hollow section

Plate element plasticity slenderness limit

Plate element yield slenderness limit

Modified compression member slenderness

Relative slenderness of CFST defined in AS5100

Section slenderness

Section plasticity slenderness limit

Section yield slenderness limit

Ȝe for the web in compression only

Ȝey for the web in compression only

Ȝ about major axis

Ȝ about minor axis

Ductility ratio or degree of utilisation in determining fire resistance

Saturated surface-dry density of concrete in Chapter 2, or ratio of the

average compressive stress in the concrete at failure to the design

yield stress of the steel as defined in BS5400

Pre-stress in the steel tube

Nominal constraining factor

Design constraining factor

Hsh

ĭ1

ĭ3

I

Ic

Iy

ij

Jc

Jo

JRd

Js

N

O

CȜ

Oe

Oep

Oey

On

Or

Os

Osp

Osy

Ȝw

Ȝwy

Ȝx

Ȝy

ȝ

ȡ

ı0

ȟ

ȟo

AIJ

AISC

Architectural Institute of Japan

American Institute of Steel Construction or Australian Institute of

Steel Construction

Notation

ASCCS

ASI

AS5100

BSI

BS5400

CFST

CFRP

CFDST

CHS

CIDECT

DBJ13-51

EC3

EC4

FR

FRP

IIW

kN

LSD

MPa

m

mm

PLR

RHS

RSI

SCC

SHS

xvii

Association for Steel-Concrete Composite Structures

Australian Steel Institute

Australian bridge design standard AS5100

British Standards Institution

British bridge code BS5400

Concrete-filled steel tubes

Carbon fibre reinforced polymer

Concrete-filled double skin tubes

Circular hollow section

International Committee for the Development and Study of Tubular

Structures

Chinese code DBJ13-51

Eurocode 3

Eurocode 4

Fire resistance in minutes

Fibre reinforced polymer

International Institute of Welding

Kilonewton

Limit states design

Megapascal (N/mm2)

Metre

Millimetre

Pre-load ratio

Rectangular hollow section

Residual strength index

Self-consolidating concrete

Square hollow section

CHAPTER ONE

Introduction

1.1 APPLICATIONS OF CONCRETE-FILLED STEEL TUBES

Using steel and concrete together utilises the beneficial material properties of both

elements. Reinforced concrete (RC) sections are one example of this composite

construction. This type of section primarily involves the use of a concrete section

which is reinforced with steel rods in the tension regions.

This book deals with another type of concrete–steel composite construction,

namely concrete-filled steel tubes (CFSTs). The hollow steel tubes can be

fabricated by welding steel plates together or by hot-rolled process, or by coldformed process. Figure 1.1 shows some typical CFST section shapes commonly

found in practice, namely circular, square and rectangular. They are often called

concrete-filled CHS (circular hollow section), SHS (square hollow section) and

RHS (rectangular hollow section), respectively.

Steel tube

t

Concrete

Steel tube

t

Concrete

d

(a)

B

Circular hollow section

(b)

Steel tube

Square hollow section

Corner

Steel tube

rext

t

D

t

Concrete

Concrete

B

(c)

D

B

Rectangular hollow section without

rounded corners

(d)

Rectangular hollow section with

rounded corners

Figure 1.1 Typical CFST sections

2

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

In Figure 1.1, d is the outer diameter of the circular section, B is the width of

the square or the rectangular sections, D is the overall depth of the rectangular

section and t is the steel wall thickness. SHS can be treated as a special case of

RHS when D equals B. For cold-formed RHS, rounded corners exist (Zhao et al.

2005), as shown in Figure 1.1(d), where rext is the external corner radius.

There is an increasing trend in using concrete-filled steel tubes in recent

decades, such as in industrial buildings, structural frames and supports, electricity

transmitting poles and spatial construction. In recent years, such composite

columns are more and more popular in high-rise or super-high-rise buildings and

bridge structures.

A few examples are presented here to give an appreciation of the scale of

such composite structures. Figure 1.2 shows the using of CFST columns in

one workshop. It is well known that the columns in a subway may be subjected to

very high axial compression. CFST is very suitable for supporting columns in

subways. One subway under construction can be seen in Figure 1.3. Figure 1.4

shows an electricity transmitting pole with CFST legs. CFST columns have very

high load-bearing capacity, which thus can be used in spacious construction. An

example is given in Figure 1.5.

Figure 1.6 shows the SEG Plaza in Shenzhen during construction. It is the

tallest building in China using CFST columns. SEG Plaza is a 76-storey Grade A

office block with a four-level basement, each basement floor having an area of

9653m2. The main structure is 291.6m high with an additional roof feature giving a

total height of 361m (Wu and Hua 2000, Zhong 1999). The steel parts of the

columns were shipped to the site in lengths of three storeys. After being mounted,

they were connected to the I-beams by bolts and were brought into the exact

position. Then, the steel tubes were filled with concrete, and the deck floors were

constructed at the same time. In this way, up to two-and-a-half storeys could be

built each week, demonstrating the efficiency of this technology. The diameter of

the columns used in the building ranges from 900mm to 1600mm. Concrete was

poured in from the top of the column. The concrete was vibrated to ensure the

compaction. The SEG Plaza was the first application of circular concrete-filled

steel tubes in super-high-rise buildings on such a large scale in China (Zhong

1999). This technology offers numerous new possibilities, such as new types of

CFST column to steel beam connections, increased fire performance of CFST

columns, etc.

In recent years, CFST columns with square and rectangular sections are also

becoming popular in high-rise buildings. Figure 1.7 presents a high-rise building

during construction using square and rectangular CFST columns, i.e. Wuhan

International Securities Building (WISB) in Wuhan, China. The main structure is

249.2m high, and was completed in 2004.

The use of CFST in arch bridges reasonably exploits the advantages of such

kind of structures (Han and Yang 2007, Zhou and Zhu 1997, Ding 2001). An

important advantage of using CFST in arch bridges is that, during the stage of

erection, the hollow steel tubes can serve as the formwork for casting the concrete,

which can reduce construction cost. Furthermore, the composite arch can be

Introduction

3

erected without the aid of a temporary bridge due to the good stability of the steel

tubular structure. The steel tubes can be filled with concrete to convert the system

into a composite structure and capable of bearing the service load. Since the

weight of the hollow steel tubes is comparatively small, relatively simple

construction technology can be used for the erection. The popular methods being

used include cantilever launching methods, and either horizontal or vertical

“swing” methods, whereby each half-arch can be rotated horizontally into position

(Zhou and Zhu 1997).

Figure 1.8 illustrates the process of an arch rib during construction. An

elevation of the bridge after construction is shown in Figure 1.9. More than 100

bridges of this type have been constructed so far in China. There is much attention

being paid both by researchers and the practising engineers to this kind of

composite bridge.

Figure 1.2 CFST used in a workshop (Han 2007)

Figure 1.3 A subway station using CFST columns (under construction)

4

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

Figure 1.4 A transmitting pole with CFST legs (Han 2007)

(a) During construction

(b) After construction

Figure 1.5 CFST in spacious construction (Han and Yang 2007)

Introduction

5

(a)

(b)

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

6

(c)

(d)

(e)

Figure 1.6 SEG Plaza under construction (Han and Yang 2007)

Introduction

7

(a)

(b)

(c)

Figure 1.7 Wuhan International Securities Building under construction (Han and Yang 2004)

8

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

(a)

(b)

(c)

Introduction

9

(d)

Figure 1.8 Elevations of the arch rib during construction (Han 2007)

Figure 1.9 Elevation of the arch after being constructed

(Han and Yang 2004)

10

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

1.2 ADVANTAGES OF CONCRETE-FILLED STEEL TUBES

It is well known that tubular sections have many advantages over conventional

open sections, such as excellent strength properties (compression, bending and

torsion), lower drag coefficients, less painting area, aesthetic merits and potential

of void filling (Wardenier 2002).

Concrete-filled tubes involve the use of a steel tube that is then filled with

concrete. This type of column has the advantage over other steel concrete

composite columns, that during construction the steel tube provides permanent

formwork to the concrete. The steel tube can also support a considerable amount of

construction loads prior to the pumping of wet concrete, which results in quick and

efficient construction. The steel tube provides confinement to the concrete core

while the infill of concrete delays or eliminates local buckling of steel tubes.

Compared with unfilled tubes, concrete-filled tubes demonstrate increased loadcarrying capacity, ductility, energy absorption during earthquakes as well as

increased fire resistance.

A simple comparison is given in Figure 1.10(a) for a column with an

effective buckling length Le of 5m, mass of steel section of 60kg/m and concrete

core strength of 40MPa. It can be seen from Figure 1.10(a) that the compression

capacity increases significantly due to concrete-filling.

Zhao and Grzebieta (1999) performed a series of tests on void-filled RHS

subjected to pure bending. The increase in rotation angles at the ultimate moment

due to the void filling was found to be 300%, as shown in Figure 1.10(b).

A schematic view of interaction diagrams for beam-columns is shown in

Figure 1.10(c). It is clear that less reduction in moment capacity is found for CFST

members. This is due to the favourable stress distribution in CFST in bending.

More discussion on CFST beam-columns will be given in Chapter 5.

Zhao and Grzebieta (1999) also performed a series of tests on concrete-filled

RHS subjected to large deformation cyclic bending. Typical failure modes are

shown in Figure 1.10(d). For unfilled RHS beams, crack initiated at the corner and

propagated across the section after several cycles. For concrete-filled RHS beams,

either localised outward folding or uniform outward folding mechanism is formed

without cracking.

The fire resistance of unprotected RHS or CHS columns is normally found to

be less than 30 minutes (Twilt et al. 1996). Figure 1.10(e) clearly shows that

concrete-filling can significantly increase the fire resistance of tubular columns.

Introduction

11

3000

2500

2000

1500

1000

500

0

Unfilled

SHS

Unfilled

CHS

Concrete-filled

SHS

Concrete-filled

CHS

Section type

(a) For columns with Le of 5m, mass of steel section of 60kg/m and

concrete cubic strength of 40MPa

Increase in rotation angles at

ultimate moment (%)

350

300

250

200

150

Low strength concrete

100

Light weight concrete

50

Normal concrete

Polyurethane

0

0

20

40

60

80

Compressive strength of filler material (MPa)

(b) Effect of concrete strength on ductility of CFST beams

(adapted from Zhao and Grzebieta 1999)

1.2

1.0

Axial load ratio

Compressive capacity (kN)

3500

0.8

0.6

CFST

Steel tube

0.4

0.2

0.0

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

Bending moment ratio

(c) Comparison of interaction diagrams (schematic view)

12

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

(i) Unfilled RHS – local (single inward folding) failure mechanism with cracking

(ii)RHS filled with low strength concrete – localised (single outward folding) mechanism without

cracking

(iii) RHS filled with normal concrete – uniform (multiple outward folding) mechanism without

cracking

(d) Comparison of cyclic behaviour (Zhao and Grzebieta 1999)

Introduction

13

Fire resistance (minutes)

250

CHS 324x6.4

SHS 304.8x304.8x9.5

200

150

100

50

0

1

Unfilled

Filled2 with

plain concrete

Filled with

3 steel

fibre reinforced

concrete

(e) Comparison of fire resistance (column height is 3.81mm, both ends fixed; load ratio is 0.46)

Figure 1.10 Advantage of CFST members

1.3 CURRENT KNOWLEDGE ON CFST STRUCTURES

1.3.1 Related Publications

Extensive research projects on tubular structures were carried out in the last 30

years under the direction of CIDECT (International Committee for the

Development and Study of Tubular Structures) and IIW (International Institute of

Welding) Subcommission XV-E on Tubular Structures. Twelve international

symposia on tubular structures have been held since 1984 (IIW 1984, Kurobane

and Makino 1986, Niemi and Mäkeläinen 1989, Wardenier and Panjeh Shahi

1991, Coutie and Davies 1993, Grundy et al. 1994, Farkas and Jámai 1996, Choo

and van der Vegte 1998, Puthli and Herion 2001, Jaurrieta et al. 2003, Packer and

Willibald 2006, Shen et al. 2008). There have been several international

conferences held through ASCCS (Association for Steel-Concrete Composite

Structures) on steel-concrete composite structures since 1985. Many papers on

concrete-filled tubes were presented at these conferences.

Several state-of-the-art reports or papers were also published recently on

concrete-filled steel tubular structures, such as Shams and Saadeghvaziri (1997),

Schneider (1998), Shanmugam and Lakshmi (2001), Nishiyama et al. (2002), Han

(2002) and Gourley et al. (2008).

A series of design guides on tubular structures have been produced by

CIDECT to assist practising engineers. The ones relevant to concrete-filled tubes

are CIDECT Design Guides No. 4 (Twilt et al. 1996), No. 5 (Bergmann et al.

1995), No. 7 (Dutta et al. 1998) and No. 9 (Kurobane et al. 2005). Other relevant

14

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

books include Han and Zhong (1996), Wardenier (2002), Wang (2002), Nethercot

(2003), Johnson and Anderson (2004), Zhao et al. (2005) and Han (2007).

Some of the books listed above are not focused on concrete-filled tubes. For

those that do, explanations of failure mechanism and mechanics are not covered in

detail. Most of the designs are based on Eurocode 4. There is a lack of comparison

of different design standards, seismic resistance has only received very little

coverage and worked examples are very limited. This book will fill these gaps.

1.3.2 International Standards

The application of CFST structures is supported by many well-known national

codes, such as the Japanese code AIJ (1997), American code AISC (American

Institute of Steel Construction 2005), British bridge code BS5400 (British

Standards Institution 2005), Chinese code DBJ13-51 (2003) and Eurocode 4

(2004). For simplicity, these codes are to be referred to as “AIJ”, “AISC”,

“BS5400”, “DBJ13-51” and “EC4” in the book.

In 2004, a new version of the Australian bridge design standard AS5100

(Standards Australia 2004) for bridge design was issued, where design guidance

for composite columns (including CFST columns) was incorporated. Tao et al.

(2008) provided useful information for future possible revision of AS5100 for

building construction. To fulfil this task, a wide range of experimental data (over

2000 test results) were used to evaluate whether AS5100 is applicable for

calculating the strength of CFST members. Effects of different parameters on the

accuracy of the strength predictions were discussed. In this book design examples

using AS5100 are also given.

1.4 LAYOUT OF THE BOOK

The following aspects of concrete-filled tubes have received little coverage in

existing design standards, design guides or relevant books, but are addressed in

this book: confinement, the effect of long-term loading, axial local compression

and pre-loads on the performance of CFST columns, seismic behaviour and postfire behaviour, worked examples, mechanics models, concrete-filled double skin

tubes, SCC (self-consolidating concrete)-filled tubes, and fibre reinforced polymer

strengthening of concrete-filled tubes.

This book contains descriptions and explanation of some basic concepts. It

not only summarises the research performed to date on concrete-filled tubular

members and connections but also compares the design rules in various standards

(Eurocode 4, BS5400 Part 5 – 2005, AS5100 Part 6 – 2004 and Chinese Standard

DBJ13-51 – 2003), and provides design examples. It also presents some recent

developments in concrete-filled tubular members and connections. Comprehensive

up-to-date references are given throughout the book.

Introduction

15

Chapter 1 outlines the application and advantages of concrete-filled steel

tubes (CFST). It also identifies the knowledge gap in CFST research and design.

Chapter 2 presents the material properties of steel tubes and concrete given in

various standards. The limit states design method is described. The differences

among the Australian, British, Chinese and European standards are pointed out to

help the readers to interpret the design comparison later in the book. CFST

members are covered in Chapter 3 (bending), Chapter 4 (compression) and

Chapter 5 (combined actions). Chapter 6 and Chapter 7 present the performance

and design methods of CFST structures under seismic loading and fire conditions.

Steel or RC beam to CFST column connection details and designing approaches

are covered in Chapter 8. Some design examples are also presented using various

codes. Finally, Chapter 9 introduces some recent developments on concrete-filled

steel tubular structures.

1.5 REFERENCES

1.

AIJ, 1997, Recommendations for design and construction of concrete filled

steel tubular structures (Tokyo: Architectural Institute of Japan).

2. ANSI/AISC, 2005, Specification for structural steel buildings, ANSI/AISC

360-05 (Chicago: American Institute of Steel Construction).

3. Bergmann, R., Matsui, C., Meinsma, C. and Dutta, D., 1995, Design guide for

concrete filled hollow section columns under static and seismic loading (Köln:

TÜV-Verlag).

4. BSI, 2005, Steel, concrete and composite bridges, BS5400, Part 5: Code of

practice for design of composite bridges (London: British Standards

Institution).

5. Choo, S. and van der Vegte, G.J., 1998, Tubular structures VIII, Proceedings

of 8th International Symposium on Tubular Structures (Rotterdam: Balkema).

6. Coutie, M.G. and Davies, G., 1993, Tubular structures V, Proceedings of

5th International Symposium on Tubular Structures (London: E & FN Spon).

7. DBJ13-51, 2003, Technical specification for concrete-filled steel tubular

structures (Fuzhou: The Construction Department of Fujian Province).

8. Ding, D., 2001, Development of concrete-filled tubular arch bridges in China.

Structural Engineering International, International Association for Bridge and

Structural Engineering, 11(3), pp. 265-267.

9. Dutta, D., Wardenier, J., Yeomans, N., Sakae, K., Bucak, Ö. and Packer, J.A.,

1998, Design guide for fabrication, assembly and erection of hollow section

structures (Köln: TÜV-Verlag).

10. Eurocode 4, 2004, Design of composite steel and concrete structures – Part

1.1: General rules and rules for buildings. EN 1994-1-1:2004, December

2004 (Brussels: European Committee for Standardization).

11. Farkas, J. and Jámai, K., 1996, Tubular structures VII, Proceedings of

7th International Symposium on Tubular Structures (Rotterdam: Balkema).

12. Gourley, B.C., Tort, C., Denavit, M.D., Schiller, P.H. and Hajjar, J.F., 2008, A

16

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

synopsis of studies of the monotonic and cyclic behaviour of concrete-filled

steel tube members, connections, and frames, Report No. NSEL-008, NSEL

Report Series, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering,

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, USA.

13. Grundy, P., Holgate, A. and Wong, B., 1994, Tubular structures VI,

Proceedings of 6th International Symposium on Tubular Structures

(Rotterdam: Balkema).

14. Han, L.H., 2002, Tests on stub columns of concrete-filled RHS sections.

Journal of Constructional Steel Research, 58(3), pp. 353-372.

15. Han, L.H., 2007, Concrete-filled steel tubular structures – theory and

practice, 2nd ed. (Beijing: China Science Press).

16. Han, L.H. and Yang, Y.F., 2004, Modern technology of concrete-filled steel

tubular structures, 1st ed. (Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press).

17. Han, L.H. and Yang, Y.F., 2007, Modern technology of concrete-filled steel

tubular structures, 2nd ed. (Beijing: China Architecture & Building Press).

18. Han, L.H. and Zhong, S.T., 1996, Mechanics of concrete filled steel tubes

(Dalian: Dalian University of Technology Press).

19. IIW, 1984, Welding of tubular structures, Proceedings of 1st International

Symposium on Tubular Structures (Oxford: Pergamon Press).

20. Jaurrieta, M.A., Alonso, A. and Chica, J.A., 2003, Tubular structures X,

Proceedings of 10th International Symposium on Tubular Structures (Lisse:

Balkema).

21. Johnson, R. and Anderson, D., 2004, Designers’ guide to EN1994-1-1

Eurocode 4: Design of composite steel and concrete structures, Part 1.1:

General rules and rules for buildings (London: Thomas & Telford).

22. Kurobane, Y. and Makino, Y., 1986, Safety criteria in design of tubular

structures, Proceedings of 2nd International Symposium on Tubular Structures

(Tokyo: Architectural Institute of Japan).

23. Kurobane, Y., Packer, J.A., Wardenier, J. and Yeomans, N., 2005, Design

guide for structural hollow section column connections (Köln: TÜV-Verlag).

24. Nethercot, D.A., 2003, Composite construction (London: Spon Press).

25. Niemi, E. and Mäkeläinen, P., 1989, Tubular structures III, Proceedings of

3rd International Symposium on Tubular Structures (London: Elsevier Applied

Science).

26. Nishiyama, I., Morino, S., Sakino, K., Nakahara, H., Fujimoto, T., Mukai, A.,

Inai, E., Kai, M., Tokinoya, H., Fukumoto, T., Mori, K., Yoshika, K., Mori,

O., Yonezawa, K., Mizuaki, U. and Hayashi, Y., 2002, Summary of research

on concrete-filled structural steel tube column system carried out under the

US – Japan cooperative research program on composite and hybrid

structures, BRI Research Paper No.147 (Tokyo: Building Research Institute).

27. Packer, J.A. and Willibald, S., 2006, Tubular structures XI, Proceedings of

11th International Symposium on Tubular Structures (London: Taylor &

Francis).

28. Puthli, R.S. and Herion, S., 2001, Tubular structures IX, Proceedings of

9th International Symposium on Tubular Structures (Lisse: Balkema).

Introduction

17

29. Schneider, S.P., 1998, Axially loaded concrete-filled steel tubes. Journal of

Structural Engineering, ASCE, 124(10), pp. 1125-1138.

30. Shams, M. and Saadeghvaziri, M.A., 1997, State of the art of concrete-filled

steel tubular columns. ACI Structural Journal, 94(5), pp. 558-571.

31. Shanmugam, N.E. and Lakshmi, B., 2001, State of the art report on steel–

concrete composite columns. Journal of Constructional Steel Research,

57(10), pp. 1041-1080.

32. Shen, Z.Y., Chen, Y.Y. and Zhao, X.Z., 2008, Tubular structures XII,

Proceedings of 12th International Symposium on Tubular Structures (London:

Taylor & Francis).

33. Standards Australia, 2004, Bridge design – Steel and composite construction,

Australian Standard AS5100 (Sydney: Standards Australia).

34. Tao, Z., Uy, B., Han, L.H. and He, S.H., 2008, Design of concrete-filled steel

tubular members according to Australian standard AS 5100. Australian

Journal of Structural Engineering, 8(3), pp. 197-214.

35. Twilt, L., Hass, R., Klingsch, W., Edwards, M. and Dutta, D., 1996, Design

guide for structural hollow section columns exposed to fire (Köln: TÜVVerlag).

36. Wang, Y.C., 2002, Steel and composite structures: Behaviour and design for

fire safety (London: Taylor & Francis).

37. Wardenier, J., 2002, Hollow sections in structural applications (Rotterdam:

Bouwen met Staal).

38. Wardenier, J. and Panjeh Shahi, E., 1991, Tubular structures IV, Proceedings

of 4th International Symposium on Tubular Structures (Delft: Delft University

Press).

39. Wu, G.L. and Hua, Y., 2000, Application of concrete filled steel tubular

column in super high-rise building-SEG Plaza. In Proceedings of the 6th

ASCCS International Conference on Steel–Concrete Composite Structures,

Los Angeles, California, edited by Xiao, Y. and Mahin, S.A. (Los Angeles:

Association for International Cooperation and Research in Steel–Concrete

Composite Structures), pp. 77-84.

40. Zhao, X.L. and Grzebieta, R., 1999, Void-filled SHS beams subjected to large

deformation cyclic bending. Journal of Structural Engineering, ASCE,

125(9), pp. 1020-1027.

41. Zhao, X.L., Wilkinson, T. and Hancock, G.J., 2005, Cold-formed tubular

members and connections (Oxford: Elsevier).

42. Zhong, S.T., 1999, High-rise concrete-filled steel tubular structures, (Harbin:

Heilongjiang Science & Technology Press).

43. Zhou, P. and Zhu, Z.Q., 1997, Concrete-filled tubular arch bridges in China.

Structural Engineering International, International Association for Bridge and

Structural Engineering, 7(3), pp. 161-166.

Material Properties and Limit States Design

19

CHAPTER TWO

Material Properties and Limit States

Design

2.1 MATERIAL PROPERTIES

Concrete-filled steel tube (CFST) consists of a steel tube and the concrete core.

The hollow steel tubes can be fabricated by welding steel plates together or by hotrolled process, or by cold-formed process. The in-filled concrete can be normal

concrete or self-consolidating concrete (SCC).

Material properties of steel and concrete specified in AS5100 Part 6

(Standards Australia 2004), BS5400 Part 5 (BSI 2005), DBJ13-51 (2003),

Eurocode 4 (2004) are summarised in this chapter. They will be used in the design

examples later in the book.

The unit MPa instead of N/mm2 is used in this chapter for the simplicity of

writing.

2.1.1 Steel Tubes

2.1.1.1 AS5100 Part 6

This Standard does not cover the steelwork of the following structures, members

and materials:

(1) Bridges with orthotropic plate decks.

(2) Cold-formed members other than those complying with AS1163

(Standards Australia 1991).

(3) Steel members for which the value of yield stress (fy) used in design

exceeds 450MPa.

(4) Steel elements, other than packers, less than 3mm thick.

The steel section shall be symmetrical, be fabricated from steel with a

maximum yield stress of 350MPa, and have a wall thickness such that the plate

element slenderness is less than the yield slenderness limit.

2.1.1.2 BS5400 Part 5

For BS5400 (2005), the sections of concrete-filled hollow steel can be either

rectangular or circular and should either:

(1) be a symmetrical box section fabricated from grade S275 or S355 steel

complying with code EN10025 (2004); or

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

20

conform to code EN10210 (2006); and

have a wall thickness of not less than bs(fy/3Es) for each wall in a

rectangular hollow section (RHS) or De(fy/8Es) for circular hollow

sections (CHS), where bs is the overall depth or width of the RHS, De is

the outside diameter of the CHS, Es is the modulus of elasticity of steel

and fy is the nominal yield strength of the steel.

The surface of the steel member in contact with the concrete filling should be

unpainted and free from deposits of oil, grease and loose scale or rust.

(2)

(3)

2.1.1.3 DBJ13-51

In DBJ13-51 (2003), the steel of CFST should comply with the Code for the design

of steel structures (GB50017 2003). There are four grades: Q235, Q345, Q390 and

Q420.

2.1.1.4 Eurocode 4

Properties should be obtained by reference to clauses 3.1 and 3.2 of Eurocode 3

Part 1.1 (2005), which apply to structural steel of nominal yield strength not more

than 460MPa.

2.1.1.5 Yield stress and tensile strength

The minimum values of yield stress (fy) and tensile strength (fu) specified in the

above four codes are summarised in Table 2.1 for steel plates, Table 2.2 for hotrolled tubes and Table 2.3 for cold-formed tubes. It can be seen that the yield stress

ranges from 200 to 460MPa while the tensile strength ranges from 300 to 720MPa.

The ratio (fu/fy) ranges from 1.11 to 1.96.

Typical stress-strain relationship of hot-rolled or fabricated mild steel tubes is

shown in Figure 2.1(a) where an obvious yield plateau exists. A typical stress–

strain relationship of cold-formed tubes is given in Figure 2.1(b) where 0.2% proof

stress is adopted to define the yield stress. More discussions on cold-formed tubes

can be found in Zhao et al. (2005).

Material Properties and Limit States Design

21

Table 2.1 Minimum values of yield stress, tensile strength and tensile to yield ratio for steel plates

(a)

Grade

AS/NZS 3678 (Standards Australia 1996)

fy (MPa)

>12

>20

d20

d32

N/A

N/A

250

250

250

250

300

280

>32

d50

N/A

250

250

280

>50

d80

N/A

240

240

270

fu

(MPa)

fu/fy

300

410

410

430

1.50

1.46 to 1.71

1.46 to 1.71

1.34 to 1.59

340

450

1.25 to 1.32

360

360

480

1.20 to 1.33

420

400

N/A

1.11 to 1.30

340

340

N/A

520

500

450

t (mm)

d8

200

250

250L15

300

300L15

350

350L15

400

400L15

450

450L15

WR350

WR350

L0

200

280

280

320

>8

d12

200

260

260

310

360

360

350

340

340

400

400

380

360

450

450

450

340

340

340

(b)

Part

Grade

Part 2

S235

S275

S355

S450

S275N/NL

S355N/NL

S420N/NL

S460N/NL

S275M/ML

S355M/ML

S420M/ML

S460M/ML

S235 W

S355 W

S460Q/QL/QL1

Part 3

Part 4

Part 5

Part 6

Grade

Q235

Q345

Q390

Q420

EN10025 (2004)

fy (MPa)

40mm < t

t d 40

mm

d 80mm

235

215

275

255

355

335

440

410

275

255

355

335

420

390

460

430

275

255

355

335

420

390

460

430

235

215

355

225

460

440

(c)

fy (MPa)

235

345

390

420

1.32

fu (MPa)

40mm < t

t d 40

mm

d 80mm

360

360

430

410

510

470

550

550

390

370

490

470

520

520

540

540

370

360

470

450

520

500

540

530

360

340

510

490

570

550

GB50017 (2003)

fu (MPa)

372 to 461

470 to 630

490 to 650

520 to 680

fu/fy

1.53 to 1.67

1.56 to 1.61

1.44 to 1.40

1.25 to 1.34

1.42 to 1.45

1.38 to 1.32

1.24 to 1.33

1.17 to 1.26

1.35 to 1.41

1.32 to 1.34

1.24 to 1.28

1.17 to 1.23

1.53 to 1.58

1.44 to 1.46

1.24 to 1.25

fu/fy

1.58 to 1.96

1.36 to 1.83

1.26 to 1.67

1.24 to 1.62

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

22

Table 2.2 Minimum values of yield stress, tensile strength and tensile to yield ratio for hot-rolled tubes

Grade

Q235

Q345

Q390

Q420

Grade

S235H

S275H

S355H

S275NH/NLH

S355NH/NLH

S420NH/NLH

S460NH/NLH

(a)

GB50017 (2003)

(b)

EN10210 (2006)

fy (MPa)

235

345

390

420

fu (MPa)

372 to 461

470 to 630

490 to 650

520 to 680

fy (MPa)

40 mm <

t d 40

t d 80

mm

mm

235

215

275

255

355

335

275

255

355

335

420

390

460

430

fu (MPa)

40 mm <

t d 40

t d 80

mm

mm

360

360

430

410

510

470

390

370

490

470

540

520

560

550

fu/fy

1.58 to 1.96

1.36 to 1.83

1.26 to 1.67

1.24to 1.62

fu/fy

1.53 to 1.67

1.56 to 1.61

1.44 to 1.40

1.42 to 1.45

1.38 to 1.40

1.29 to 1.33

1.22 to 1.28

Table 2.3 Minimum values of yield stress, tensile strength and tensile to yield ratio for cold-formed

tubes

(a)

AS1163 (1991)

(b)

GB50018 (2002)

Grade

C250, C250L0

C350, C350L0

C450, C450L0

fy (MPa)

250

350

450

Grade

Q235

Q345

Q390

Q420

fy (MPa)

235

345

390

420

fu (MPa)

320

430

500

fu (MPa)

372 to 461

470 to 630

490 to 650

520 to 680

fu/fy

1.28

1.23

1.11

fu/fy

1.58 to 1.96

1.36 to 1.83

1.26 to 1.67

1.25to 1.62

Material Properties and Limit States Design

23

Table 2.3 Minimum values of yield stress, tensile strength and tensile to yield ratio for cold-formed

tubes (continued)

Grade

CHS

S275NH

S275NLH

S355NH

S355NLH

S460NH

S460NLH

RHS/SHS

S275NH

S275NLH

S355NH

S355NLH

S460NH

S460NLH

(c)

EN 10219 (1992)

t d 16 mm

275

fy (MPa)

16 mm < t d 40 mm

265

fu (MPa)

t d 40 mm

370 – 510

1.35 to 1.92

355

345

470 – 630

1.33 to 1.83

460

440

550 – 720

1.20 to 1.63

t d 16mm

275

16mm < t d 24mm

265

t d 24mm

370 – 510

1.35 to 1.92

355

345

470 – 630

1.33 to 1.83

460

440

550 – 720

1.20 to 1.63

Stress

fu

fy

Es

Strain

(a) Hot-rolled or fabricated mild steel tubes

Stress

fu

fy

0.2% Proof stress

Es

0.2%

Strain

(b) Cold-formed tubes

Figure 2.1 Schematic view of stress–strain curves for steel tubes

fu/fy

24

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

2.1.2 Concrete

2.1.2.1 AS5100 (2004)

In this code, concrete shall be of normal density and strength, meet the

requirements of AS5100 Part 5, and have a maximum aggregate size of 20mm.

Reinforcement is not normally required in concrete-filled hollow steel compression

members, but if used it shall meet the requirements of AS5100 Part 5.

The characteristic compressive cylinder strength at 28 days (fƍc) ranges from

25MPa to 65MPa with a saturated surface-dry density in the range of 2100kg/m3

to 2800 kg/m3. The modulus of elasticity of concrete can be estimated as U1.5 u

0.043fcm, where fcm is the mean value (in MPa) of the compressive strength of

concrete at the relevant age. For concrete-filled steel tubes, the modulus of

elasticity of concrete should be taken as one half of the material value.

Consideration shall be given to the fact that the modulus of elasticity varies ±20%.

2.1.2.2 BS5400 (2005)

The concrete in this code should be of normal density (not less than 2300kg/m3)

with a characteristic 28-day cubic strength (fcu) of not less than 20N/mm2 for

concrete-filled tubes. A nominal maximum aggregate size of 20mm is specified.

The characteristic properties of concrete, reinforcement and pre-stressing

steels should be determined in accordance with Part 4. For sustained loading, it

should be sufficiently accurate to assume a modulus of elasticity of concrete equal

to one half of the value used for short-term loading.

2.1.2.3 DBJ13-51 (2003)

In code DBJ13-51-2003, the characteristic 28-day cubic strength (fcu) should not be

less than 30MPa.

The modulus of elasticity of concrete is given by Ec = 105/(2.2 + 34.7/fck),

where fck is the standard compressive strength, in MPa.

2.1.2.4 Eurocode 4 (2004)

It is regulated that unless otherwise given by Eurocode 4, properties should be

obtained by reference to EN1992-1-1, clause 3.1, for normal concrete and to

EN1992-1-1, clause 11.3, for lightweight concrete. This part of EN1994 does not

cover the design of composite structures with concrete strength classes lower than

C20/25 and LC20/22 or higher than C60/75 and LC60/66.

In EN1992-1-1, the compressive strength of concrete (f’c) is denoted by

concrete-strength classes which relate to the characteristic (5%) cylinder strength

Material Properties and Limit States Design

25

or the cube strength in accordance with EN206-1 (2002). The strength classes in

this code are based on the characteristic cylinder strength determined at 28 days.

The modulus of elasticity of concrete is equal to Ec = 22,000 (fƍc/10)0.3. The

unit of fƍc should be in MPa.

2.1.2.5 Concrete strength

Concrete properties specified in the above-mentioned four codes are summarised in

Table 2.4 where some values are rounded off to be consistent in presentation. The

modulus of elasticity of concrete (Ec) is not given in Table 2.4 since it depends on

the density and compressive strength of concrete. In general, Ec lies in the range of

20,000MPa to 40,000MPa, which is about 1/10 to 1/5 of Es (modulus of elasticity

of steel).

Table 2.4 Material properties of concrete

Standard

AS5100

BS5400

Characteristic

compressive

cylinder

strength at 28

days fƍc (MPa)

25

32

40

50

65

N/A

DBJ13-51

N/A

Eurocode 4

20

25

30

40

50

60

Standard

compressive

strength

fck (MPa)

Design

compressive

strength

fc (MPa)

Standard

tensile

strength

ftk (MPa)

Tensile

strength

ft (MPa)

N/A

N/A

N/A

20

25

30

40

50

60

20

27

32

39

45

50

13.3

16.7

20.0

26.7

33.3

40.0

14.3

19.1

23.1

27.5

31.8

35.9

13.3

16.7

20.0

26.7

33.3

40.0

2.0

2.3

2.5

2.8

3.2

N/A

N/A

2.0

2.4

2.6

2.9

3.0

3.1

1.5

1.8

2.0

2.5

2.9

3.1

1.1

1.2

1.3

1.5

1.7

1.9

1.4

1.7

1.9

2.0

2.1

2.2

1.0

1.2

1.3

1.7

1.9

2.1

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

26

A typical stress–strain relationship of high strength concrete and normal

strength concrete is shown in Figure 2.2.

Stress

High strength concrete

fc

fc

Normal strength concrete

Ec

Hc

Hc

Strain

Figure 2.2 Schematic view of stress versus strain curves for concrete

2.2 LIMIT STATES DESIGN

Limit states design (LSD) is a design method in which the performance of a

structure is checked against various limiting conditions at appropriate load levels.

The limiting conditions to be checked in structural steel design are ultimate limit

state and serviceability limit state. Ultimate limit states are those states concerning

safety, such as exceeding of load-carrying capacity, overturning, sliding and

fracture due to fatigue or other causes. Serviceability limit states are those in which

the behaviour of the structure is unsatisfactory, and include excessive deflection,

excessive vibration and excessive permanent deformation.

As mentioned in Chapter 1, design examples will be given in this book in

accordance with BS5400 (2005), DBJ13-51 (2003), Eurocode 4 (2004) and

AS5100 (Standards Australia 2004). A brief description of the limit states design is

given in this section since all the standards adopt the LSD approach.

2.2.1 Ultimate strength limit state

2.2.1.1 AS5100 Part 6

For the strength limit state design, the structure is deemed to be satisfactory if its

design load effect does not exceed its design resistance. In AS5100 this criterion is

described as:

S* d I R u

(2.1)

Material Properties and Limit States Design

27

where S* is the design action effects resulted from the design loads at the ultimate

limit state, Ru is the nominal capacity and I is the capacity factor. For capacity in

bending, I is taken as 0.9. For capacity in compression, I is taken as 0.9 for a steel

component and 0.6 for a concrete component.

Load factors are used in determining the design action effects (S*) as

specified in AS/NZS1170.0 (Standards Australia 2002). For example, a load factor

of 1.2 is given to the dead load and a load factor of 1.5 is given to the live load for

static design.

2.2.1.2 BS5400 Part 5

For a satisfactory design the following relation should be satisfied in BS5400

(2005):

S* d R *

(2.2)

where R* is the design resistance and S* is the design effects.

R* = Function (fk)/(rm1 rm2), fk is the characteristic (or nominal) strength of the

material; rm1 is intended to cover the possible reductions in the strength of the

materials in the structure as a whole as compared with the characteristic value

deduced from the control test specimen; rm2 is intended to cover possible

weaknesses of the structure arising from any cause other than the reduction in the

strength of the materials allowed for in rm1, including manufacturing tolerances.

Material properties factors are used in determining the design resistance R*.

A factor of 1.5 is used for concrete, whereas a factor of 1.05 is used for steel.

S* = rf3 (effects of rf1 rf2 Qk), rf1 takes account of the possibility of

unfavourable deviation of the loads from their nominal values; rf2 takes account of

the reduced probability that various loadings acting together will all attain their

nominal values simultaneously; rf3 is a factor that takes account of inaccurate

assessment of the effects of loading, unforeseen stress distribution in the structure,

and variations in dimensional accuracy achieved in construction.

Load factors are used in determining the design action effects (S*) as

specified in BS5400 Part 2 (BSI 2006). For example, a load factor of 1.2 is given

to the dead load and a load factor of 1.5 is given to the live load for static design.

2.2.1.3 DBJ13-51

In DBJ13-51 (2003), the strength limit state criterion is expressed as:

J oS d R

(2.3)

where S is the design action effect, R is the ultimate resistance and J0 is the

coefficient of the building importance which varies from 0.9 to 1.1. The dead load

factor is 1.2 and the live load factor is 1.4. The material property factor is 1.4 for

concrete and about 1.12 for steel.

Concrete-Filled Tubular Members and Connections

28

2.2.1.4 Eurocode 4

In Eurocode 4 (2004), the limit state design is in accordance with Eurocode 0

(2002), and this criterion is described as:

1

Ed d R d

R X d, i ; a d

(2.4)

J Rd

^

`

where Ed is the design value of the effect of actions such as internal force, moment

or a vector representing several internal forces or moments and Rd is the design

value of the corresponding resistance.

JRd is a partial factor covering uncertainty in the resistance model, plus

geometric deviations if these are not modelled explicitly; Xd,i is the design value of

material property i. Material property factors are used in determining the design

resistance.

Load factors are used in determining the design action effects (Ed) as

specified in Eurocode 2 (2004) and Eurocode 3 (2005).

Load factors, materials factors and capacity factors for the four standards

mentioned above are summarised in Table 2.5.

Table 2.5 Summary of load factors, material factors and capacity factors

Standard

Criterion

Load factors

Live

AS5100

S* d I R u

1.5

Material

property

factors

Dea

d

Jc

1.2

N/A

Capacity factors

Js

0.9 on capacity in

bending

N/A

0.9 on steel capacity in

compression

0.6 on concrete capacity

in ompression

1.5

1.2

1.5

1.05

N/A

DBJ-13-51

S* d R *

Jo S d R

1.4

1.2

1.4

1.12

N/A

Eurocode 4

Ed d R d

1.5

1.1

1.5

1.00

N/A

BS5400

2.2.2 Serviceability limit state

For serviceability limit state, the deflection of the structure (G) should not exceed

certain deformation limit (Gmax). For example, the serviceability limit states for the

vertical deflection in a simply supported beam can be expressed as (Eurocode 3

Material Properties and Limit States Design

2004):

G d G max

29

(2.5)

where Gmax is the sagging in the final state relative to the straight line joining the

supports. It contains three components as shown below:

G max G1 G 2 G o

(2.6)

in which, Go is the hogging of the beam in the unloaded state, G1 is the variation of

the deflection of the beam due to the permanent loads immediately after loading,

and G2 is the variation of the deflection of the beam due to the variable loading plus

the long-term deformations due to the permanent load.

The load factors used to calculate the deflection (G) are taken as unity or

smaller than those for ultimate strength limit states, e.g. 1.0 for the dead load and

0.7 for the live load in the Australian Standard AS1170.0 (2002).

It should be noted that, for concrete-filled steel tubular structures, relevant

stages in the sequence of construction shall be considered.

2.3 REFERENCES

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

8.

9.

BSI, 2006, Steel, concrete and composite bridges, BS5400, Part 2:

Specification for loads (London: British Standards Institutions).

BSI, 2005, Steel, concrete and composite bridges, BS5400, Part 5: Code of

practice for design of composite bridges (London: British Standards

Institution).

DBJ13-51, 2003, Technical specification for concrete-filled steel tubular

structures (Fuzhou: The Construction Department of Fujian Province).

EN206, 2002, Concrete – Part 1: Specification, performance, production and

conformity,

EN206-1:2002

(Brussels: