PHOTOGRAPHIC.pdf

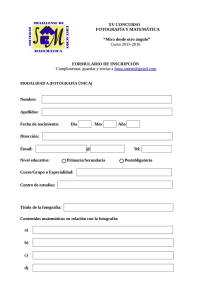

Anuncio