English spelling and pronunciation # Pronunciación en inglés

Anuncio

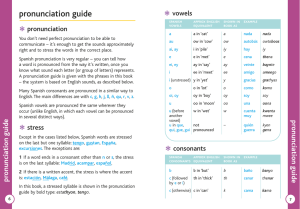

INTRODUCTION. English words have suffered throughout history several graphic oscillations. Old English (OE) and Middle English (ME) were basically oral languages and everything we can deduce from previous periods is based on the data that we encounter in orthographic variants and their interpretations. Firstly; we must take into account that every alphabetic system is born in order to represent as much accurate as possible the phonetic sequence (The ideal system should have a one−to−one correspondence). Secondly; orthography nowadays is understood as a conservative and stable convention but it was not so in the past (There were not fixed rules in the English language until the 18th c.) With the propagation of the learning, the criterion for correctness has also changed, and, consequently, written language has achieved a bigger autonomy with regard to the oral one. FROM OLD ENGLISH TO MIDDLE ENGLISH. If we take a deeper look at the history of the English grapho−phonology, it is easy to observe that there has been a progressive removal between graphemes and phonemes. In OE, graphemes coincided with pronunciation (You could foresee the way a word sounded, with some exceptions, of course, such as the letters <c> and <g>). The first alphabet used in the British Isles was the Futhark, which depending on the region, it suffered various modifications that permitted its appropriate adaptation to the idiosyncratic pronunciation of words, thus in Great Britain it had up to 31 symbols. But Futhark was substituted later on by the Roman alphabet, although some symbols were kept until the end of the Middle Ages to represent sounds, e.g. Thorn, Wynn and Eth. SOME 15TH CENTURY CHANGES IN SPELLING AND PRONUNCIATION During the period of ME there were a series of great orthographic alterations, such as the appearance of new digraphs, e.g. <ch>, <ph> or <wh>; letters very little used before in English, e.g. <j, v, w, q, z>, and finally the change in vowels, thus Fifteenth−century spelling conventions exhibit the following characteristics: vowel length was indicated by doubling the vowel, ee, oo (rarely aa, ij; cf. ou/ow), or by post−consonantal e (Görlach, M. 1991: 46). Some examples: • Chord (Present−day English)>Cord (OE) • Jack (PrE)>Iakke (OE) • Peek (PrE)>Pyke (OE) • Hoof (PrE)>Hof (OE) In the period of Early modern English (EModE), some changes continued, but they were merely orthographic; however, these changes that had influenced the written code were dependant on calligraphic aspects as well, for instance, in the 12th c. the English manuscripts substituted the calligraphic ones (Carolovingian and Insular writings Vs. Gothic writings). On the one hand, they could profit from the space in a better way than before; on the other hand, this calligraphy darkened the reading of letters like <i, u> whenever they appeared in combination with some consonants, e.g. <m, n, l, v> and so, in these cases, the scribes used to write an <o> instead, but amazingly spelling is often more variable in early prints than in good manuscripts. (Görlach, M. 1991: 45). In order to be able to see the changes, we must trust in the written code because we have not any record of 1 what was the pronunciation like at that time; that is why, apparently, texts should be a reliable resource of information since Modern spelling still largely represents medieval pronunciation (Knowles, J. 1997: 83). Following this line of thinking, let's take, for example, some proverbs which theoretically should have any kind of poetic device, e.g. rhyme, so that they can be easily remembered: • All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy • The course of true love never did run smooth • He who gives fair words feeds you with an empty spoon • Hoist your sail when the wind is fair • Take the rough with the smooth • When ignorance is bliss, ´tis folly to be wise In all of these examples, the highlighted words ought to be similar in pronunciation, that is, there should be a pattern, a rhyme that links them; so the obvious conclusion is that, even though they are uttered differently today, in the past, they were, phonetically speaking, similar. Another example: Our two souls, therefore, which are one, Though I must go, endure not yet A breach, but an expansion, Like gold to airy thinness beat. (Donne, A Valediction: Forbidding Mourning, 21−25) Here, the poetic scheme is intended to be: a, b, a, b; but, according to present−day pronunciation what we have is: a, b, c, d. THE GREAT VOWEL SHIFT With regard to the vocalic system, English has always had two series of phonemes, long and short. In OE the vocalic quantity was independent from the type of syllable (There was a lack of correspondence); moreover, there was a number of vocalic phonemes that do not exist today. Afterwards, during the ME period, the Anglo−Saxon diphthongs were monophthongised, e.g. heofon>heaven (Also known as the shortening in vowel quantity) since they were very weakened, and at the same time some others emerged from French or Scandinavian, but not all of them have survived. Strong stressed short vowels became long, e.g. hof /o/>hoof [u:]/[oo] and the long ones were diphongised, e.g: Hus /u:/> House [au] Many phonic changes take place as a result of the universal principle of the economy of language (Minimum effort law), which justifies the tendency to obtain an articulatory facility. In addition to this, there are other reasons for language to change, e.g. an expressive reason, either objective and collective or subjective and individual (the necessity of naming new things), a communicative reason (The contact among people), the stylistic reason or the sociolinguistic reason, and so on and so forth. Nevertheless, the linguistic change is not generalised until it becomes something legal, that is, it is institutionalised, for instance, in the case of the ME (English took over French in the court and Latin in the church, schools and universities). Anyway, there are many more causes than these that provoked a revision of the English spelling and a change in pronunciation (As we may see with the Great Vowel Shift), for example: The invention of the printing press, the increase of translations, the influence of other languages such as French, Spanish, Italian, German; 2 the deeper study of classical languages like Hebrew (apart from Latin and Greek, of course), the appearance of new social classes like the bourgeoisie, the birth of imperialism (Expansion of the English language and contacts with other non−European Languages); basically, that period (The Renaissance) was a pot of boiling ideas and all kind of movements which unsurprisingly revolutinised the world's views (Thoughts, philosophies, etc) and consequently language, due to the fact that both are closely related. In the Middle Ages orthography was continuously open to modifications. There were different canons of spelling. Runic Alphabet 3