Historia del dinero

Anuncio

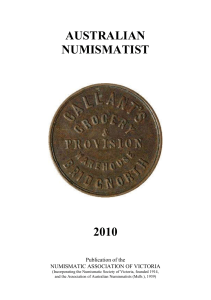

The History of Money It has been a central part of our lives and our civilizations for more than 4,000 years. Money. And over this expanse of human history, the physical form money has taken has evolved from seashells to digital bits of data Before there was money It's hard to think of a world without money. But for most of human history, money had not existed. The earliest human societies didn't need money. Instead, goods were bartered or traded. Bartering is our earliest form of payment an original substitute for money. However, barter only worked when both parties wanted the goods of offer for exchange. As societies developed and commerce became more complex, a new way around these problems was needed. The Cowry shell The oldest written records of money come 4,500 years ago from ancient Mesopotamia, now known as southern Iraq. About 3,500 years ago tiny Cowry shells from the Indian Ocean were used in China as a means of exchange. Even the Chinese symbols used today for buying, bartering and selling incorporate the symbol for the Cowry shell. These shells were still being used as accepted currency in parts of Africa as late as the 19th century. From silver to the first coins Ancient Mesopotamian inscriptions describe payments being made with weighed amounts of silver. Since then, weighed amounts of metal have been used as money in many parts of the world, and this practice led to the invention of coins. Coins are just pieces of metal marked with a special design that indicates its use as money. Unlike precious metals, however, coins do not need to have an intrinsic value in themselves. They only represent a token of value. 1 True coinage developed in Asia Minor during the 7th century BC in what is now Turkey. Weighed lumps of 'electrum' a mixture of gold and silver were used by the Lydians as money. The Lydians stamped their lumps of electrum with various images a practice known as minting to guarantee their purity and authenticity. These irregular lumps were eventually standardized in shape and weight. The same idea was simultaneously developed elsewhere, albeit using different metals. Copper lumps were used in both what are now Southern Russia and Italy, bronze used in China, silver rings in Thailand, and gold and silver bars in Japan. As soon as coins became commonplace, however, people realized their limitations chiefly their weight and bulk. And, as trade began to take on a less regional and more international perspective, a new type of money was needed to make larger transactions easier. The emergence of banks and banknotes During the 10th century, the Chinese began the process of depositing their heavy iron coins with local merchants in return for hand written receipts. The holder of these receipts would then use them to purchase goods from the merchant when needed. This system acted as an early version of pre−paid commerce. The Chinese government, who issued the iron coins, adopted the paper receipt system in the early 11th century, printing receipts with fixed face values. Soon, this practice evolved and spread, with gold and silver as well as coins being deposited often with Goldsmiths in exchange for paper receipts. The goldsmiths profited from the gold, silver and iron coin deposits by lending these valuable items out to third parties in return for interest charged. Eventually banks emerged, assuring the value of notes they issued into circulation. Incidentally, the first banks exchanged notes for coins and precious metals on benches, and this is where the term bank comes from: banco is the Italian word for bench. But it was the Swedish Stockholm Bank that issued the first official printed notes in 1661. Notes soon replaced the old pre−paid paper receipt system and banknotes had become the common form of public currency. Forgery and the frequency of issuers going out of business led to the practice of governments taking over the issuance of notes and coins. Gold and silver reserves were used to back up the value of the currency issued and these reserves were stored in highly guarded and fortified places, such as England's Tower of London. However, even banknotes soon demonstrated their limits. Governments soon discovered that printing and circulating cash and storing and protecting the reserves that secured the value of the cash issued into circulation was both expensive and risky: Paper currency in particular was prone to loss due to fire, moisture and perhaps the greatest peril to the system forgery. Soon banks sought out better currency systems than paper money. 2 Cheques and Plasticthe Dawn of the Modern Age of Money The use of cheques, printed by issuing banks, brought back the practice of paper receipts, but this time the exchange notes were used as post−payment rather than as pre−payment. Cheques were used between one individual and another, between a consumer and a merchant, between merchants and even between banks. This new system allowed money to change hands without the need for exchanging actual bank notes or coins. Over the past twenty years, with the advent of computers and international telecommunications, most of the world's transactions are conducted digitally. Value is transferred from one account to another, from one bank to another without the need for exchanging bills and coins physically. Plastic cards holding personal data on magnetic stripes were developed to give people virtual access to their money. Today, debit and credit cards, along with cheques, linked to the user's bank account enable nearly every kind of payment. As with all previous stages in the evolution of money, however, even cheques and plastic cards have their limitations. For example, debit and credit cards require telephone lines, third party authorizations, signatures and PIN codes, all slowing down the transaction process and limiting the places where such transactions can take place. Furthermore, the infrastructure required to facilitate their use is expensive. Using a credit card to make a ten−cent purchase is just not cost effective. Notes and coins are still the most suitable means of making small everyday payments. Today, money is evolving to its next stage one that combines the convenience of plastic with the flexibility and cost−effectiveness of cash. This newest stage in the evolution of money is electronic cash. Electronic Cash and Smart Cards: A Payment Solution for the 21st Century Despite the popularity of credit and debit cards, the vast majority of all transactions worldwide are still carried out with cash. Cash remains the only universally acceptable form of payment. Even when a retailer doesn't accept a particular credit card, cash will be taken. When it is, the exchange of value is immediate: No clearing or processing is needed, no signatures and no electronic transfers required. 3 A true cash alternative, replicating the core features of notes and coins, would have to be universally recognized and accepted. Like cash, transactions would have to offer immediate transfers of value and must enable easy person−to−person payments. Electronic cash must also be able to work in different currencies and would have to be secure from forgery and malfunction. Bibliography http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/moolah/history.html http://lglwww.epfl.ch/~jkienzle/old/Digital_Money/node5.html http://www.sics.se/~psm/payments/sld013.htm http://www.mondex.ca/eng/facts/historyofmoney.cfm?pg=facts 4