animal genetic resources ressources génétiques animales recursos

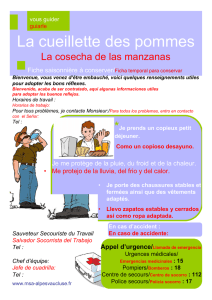

Anuncio