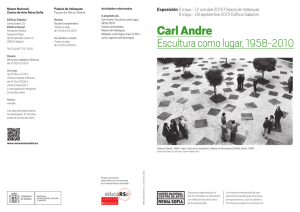

Carl Andre: La importancia del lugar - von Eva Meyer

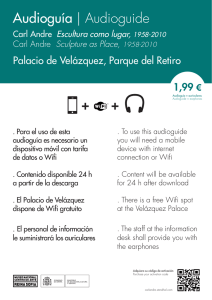

Anuncio