Edulcorantes Artificiales en el Tratamiento de la Obesidad: Qué dice

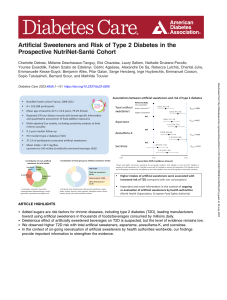

Anuncio

Edulcorantes Artificiales en el Tratamiento de la Obesidad: Qué dice la evidencia?? Dra. Catalina Fuentes G Nutrióloga Hospital Clínico FACh Clínica las Lilas Placer por lo dulce, azúcar y obesidad Edulcorantes artificiales: no tan rápido! Mecanismos propuestos para el “daño” Evidencia actual Conclusiones El ser humano nace con una fuerte preferencia por el sabor dulce…. Se estima que.. • La ingesta promedio de azúcar agregada en USA, corresponde a un 15.8% de las calorías totales. • 47% de esas calorías viene dado por bebidas azucaradas • El consumo de este tipo de bebidas aumentó 135% entre 1977 y 2001 • Si se agrega a la dieta 1 lata de bebida azucarada=150 kcal (40-50g azúcar)por día (sin modificar el resto)------ +6.75 kg/año Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:274–88 will reduce the prevalence of obesity Pro v Con Debate: Role of sugar sweetened beverages in obesity obesity-related diseases F. B. Hu Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases 1,2 1 Departments of Nutrition and Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; 2Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA F. B. Hu1,2 1 Departments of Nutrition and Epidemiology, Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA, USA; 2Channing Division of Network Medicine, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA Received 17 March 2013; revised 1 April 2013; accepted 1 April 2013 Address for correspondence: FB Hu, Department of Nutrition, Harvard School of Public Health, 665 Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02115, USA. E-mail: frank.hu@channing.harvard.edu Summary Received 17 March 2013; revised 1 April 2013; accepted 1 April 2013 Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are the single largest source of added sugar and Address for correspondence: Hu, the top source of energy intake in the U.S. diet. In this review, we evaluate FB whether Department of Nutrition, Harvard School there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing SSB consumption will reduceof Public Health, 665 Huntington Ave, Boston, the prevalence of obesity and its related diseases. Because prospective cohort 02115, USA. studies address dietary determinants of long-termMAweight gain and chronic disE-mail: frank.hu@channing.harvard.edu eases, whereas randomized clinical trials (RCTs) typically evaluate short-term effects of specific interventions on weight change, both types of evidence are critical in evaluating causality. Findings from well-powered prospective cohorts have consistently shown a significant association, established temporality and demonstrated a direct dose–response relationship between SSB consumption and long-term weight gain and risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D). A recently published meta-analysis of RCTs commissioned by the World Health Organization found that decreased intake of added sugars significantly reduced body weight (0.80 kg, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.39–1.21; P < 0.001), whereas increased sugar intake led to a comparable weight increase (0.75 kg, 0.30–1.19; P = 0.001). A parallel meta-analysis of cohort studies also found that higher intake of SSBs among children was associated with 55% (95% CI 32–82%) higher risk of being overweight or obese compared with those with lower intake. Another metaanalysis of eight prospective cohort studies found that one to two servings per day of SSB intake was associated with a 26% (95% CI 12–41%) greater risk of developing T2D compared with occasional intake (less than one serving per month). Recently, two large RCTs with a high degree of compliance provided convincing data that reducing consumption of SSBs significantly decreases weight gain and adiposity in children and adolescents. Taken together, the evidence that decreasing SSBs will decrease the risk of obesity and related diseases such as T2D is compelling. Several additional issues warrant further discussion. First, prevention of long-term weight gain through dietary changes such as limiting consumption of SSBs is more important than short-term weight loss in reducing the Summary Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are the s the top source of energy intake in the U.S. d there is sufficient scientific evidence that de the prevalence of obesity and its related studies address dietary determinants of lo eases, whereas randomized clinical trials effects of specific interventions on weigh critical in evaluating causality. Findings fr have consistently shown a significant ass demonstrated a direct dose–response relati long-term weight gain and risk of type 2 meta-analysis of RCTs commissioned by t that decreased intake of added sugars signi 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.39–1.21; intake led to a comparable weight increa parallel meta-analysis of cohort studies a among children was associated with 55% ( overweight or obese compared with tho analysis of eight prospective cohort studies of SSB intake was associated with a 26% developing T2D compared with occasion month). Recently, two large RCTs with a convincing data that reducing consumption gain and adiposity in children and adolesc decreasing SSBs will decrease the risk of ob is compelling. Several additional issues wa tion of long-term weight gain through diet tion of SSBs is more important than sh prevalence of obesity in the population. individual becomes obese, it is difficult to l should consider the totality of evidence r (e.g. from short-term RCTs only). Finally, harm on health against SSBs is strong, we absolute proof before allowing public hea Keywords: Diabetes, nutrition, obesity, su obesity reviews (2013) 14, 606–619 Fácil: cambiemos las bebidas por agua! The negative impact of consuming sugar-sweetened beverages on weight and other health outcomes has been increasingly recognized; therefore, many people have turned to high-intensity sweeteners like aspartame, sucralose, and saccharin as a way to reduce the risk of these consequences. However, accumulating evidence suggests that frequent consumers of these sugar substitutes may also be at increased risk of excessive weight gain, metabolic syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. This paper discusses these findings and considers the hypothesis that consuming sweet-tasting but noncaloric or reduced-calorie food and beverages interferes with learned responses that normally contribute to glucose and energy homeostasis. Because of this interference, frequent consumption of high-intensity sweeteners may have the counterintuitive effect of inducing metabolic derangements. body weight, and other related co-morbidities. A secon goal is to identify and examine the types of physiologic mechanisms that could underlie such adverse health co sequences. A third aim is to consider factors that can ma studies into the effects of artificial sweeteners on ener and body weight regulation difficult to interpret. • Potencial valor de reemplazar la sacarosa de bebidas y otros alimentos por endulzantes no calóricos… Sweeteners and health Consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB; see Glossary) has been increasingly associated with negative health outcomes such as being overweight, obesity, type 2 diabetes (T2D), and metabolic syndrome, for reviews, see [1–5]. Based largely on these associations, many researchers and healthcare practitioners have proposed that noncaloric, high-intensity sweeteners provide a beneficial alternative in foods and beverages [6–10].There is no doubt that replacing caloric with noncaloric sweeteners reduces the energy density of foods and beverages. However, whether reducing energy density in this manner always translates into reduced energy intake, lower body weight, and improved metabolic health is much less certain. Recent reviews of studies spanning at least the past 40 years have concluded that high-intensity sweeteners are potentially helpful [11], harmful [12], or have as yet unclear effects [9,13–15] with regard to regulation of energy balance or other metabolic consequences. One purpose of this opinion paper is to summarize and evaluate recent research that is consistent with the rather counterintuitive claim that consuming high-intensity sweeteners may promote excess energy intake, increased Corresponding author: Swithers, S.E. (swithers@purdue.edu). Keywords: obesity; diabetes; sweeteners. 1043-2760/$ – see front matter ! 2013 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2013.05.005 Glossary Artificially sweetened beverages (ASB): also known as ‘diet’ soft drinks beverages manufactured with one or more high-intensity sweeteners in plac of energy-yielding sugars like sucrose or high-fructose corn syrup with th purpose of reducing or eliminating calories. Body mass index (BMI): used as an index of risk for weight-related healt outcomes and is calculated as (kg/m2). In adults BMIs of 18.5–24.9 ar considered to be within the normal range, whereas BMIs from 25 to 29.9 ar classified as overweight and a BMI greater than 30 is classified as obese. Hazard ratio (HR) and odds ratio (OR): statistical measures of how often a event occurs in one group compared to another. A HR or OR of 1 means there i no difference between the groups and an HR or OR >1 means there is a increased likelihood that the event will occur in the group of interest relative t the comparison group. High-intensity sweeteners: also known as low-calorie sweeteners, artificia sweeteners, non-nutritive sweeteners, or noncaloric sweeteners are chemical that produce the perception of sweet taste at very low concentrations. High intensity sweeteners currently used commonly in foods and beverages includ sucralose, aspartame, saccharin, and acesulfame potassium, as well as newl approved extracts from the plant Stevia rebaudiana. Although some high intensity sweeteners can be metabolized by the body, foods and beverage typically contain them in such small quantities that even those that can b metabolized contribute minute amounts of energy to the diet. Incretin hormones: hormones such as glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) an glucose-dependent insulinotropic peptide (GIP) that are released from L cell and K cells in the intestine, respectively, and serve to enhance the release o insulin from beta cells, slow the rate of gastric emptying, and may contribute t satiety. Metabolic syndrome: a group of factors that occur together and contribute t increased risk for coronary artery disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes (T2D Typical definitions require three or more of the following: blood pressure >130 85 mmHg; fasting blood glucose >100 mg/dl; large waist circumference (me >102 cm, women >89 cm); low high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholestero (men <40 mg/dl; women <50 mg/dl); triglycerides >150 mg/dl. Post-prandial glucose homeostasis: following meals (post-prandial) levels o glucose in the blood are tightly regulated by the release of a variety o hormones that contribute to clearance of glucose. For example, release o insulin from the beta cells of the pancreas is required to move sugar from th blood into cells. Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSB): also known as ‘regular’ soft drinks manufactured with one or more caloric sweeteners such as sucrose or high fructose corn syrup. Thermic effect of food: increase in metabolic rate after consumption of a mea related to energy required to process and metabolize the consumed food. Type 2 diabetes: chronic elevation of blood glucose due to insulin resistanc that is also characterized by impaired incretin secretion. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism, September 2013, Vol. 24, No. 9 4 El valor de los endulzantes para disminuir el aporte total de calorías es mayor en productos líquidos Intense sweeteners, energy intake and the control of body weight F Bellisle and A Drewnowski Table 2 Comparison of sugar-reduced and regular foods and drinks Type of food or drink Cola drinks Fruit drinks Cocoa Hard candies Drinking yogurt Yogurt nonfat Fruit Pie Gelatin Pudding RTE cereal Muesli Cookies Chocolate syrup Chocolate Chewing gum Regular Sugar-reduced or sugar-free CHO content (per 100 g) Energy content (kcal per 100 g) CHO content (per 100 g) Energy content (kcal per 100 g) 10.2 14 10.9 100 12.8 13.8 33.6 13.6 21.2 90 68 33 61 59 120 40 56 50 375 72 75 237 57 131 360 380 445 261 513 500 0 1.9 4.4 93 4.0 4.9 26 0 8.6 90 69 32.5 32.9 49 60 2 11 25 253 42 44 171 8 64 360 344 445 140 510 300 energy density of beverages; the reduction is smaller for semi-liquid food products, and can be very small for solid foods. The impact of intense sweeteners on energy intakes may, therefore, largely depend on the energy density of the 1998b). Typically, preload volume is adjusted by the addition of water preload and energy is adjusted by the addition of non-caloric components (intense sweeteners or fat replacements), whereas preload nutrient composition is determined European Journal of Clinical Nutrition (2007) 61, 691–700 Placer por lo dulce, azúcar y obesidad Edulcorantes artificiales: no tan rápido! Mecanismos propuestos para el “daño” Evidencia actual Conclusiones Key: SSB 30 150 100 50 0 ASB SSB 100 80 20 10 60 40 Change in per capita soda availability since 1962 (litres) Change in overweight and obesity prevalence since 1962 (Percent) ASB Overweight and obesity Per capita consump!on in 2000 (litres) Aumento de la prevalencia de obesidad y sobrepeso a pesar de la incorporación de Opinion Trends in Endocrinology an [(Figure_1)TD$IG] edulcorantes no calóricos cross-sectionally, b study, SSB intake males only in the were no increased body fat percentag ferences in outcom Fowler et al. stud younger subjects, a However, neither s sumption was ass weight gain or incr Metabolic syndrom A number of studie 20 ic syndrome for c cohorts [6,20–22] ( 0 0 increase in the risk 1974 1980 1994 2000 Year consuming ASB ra TRENDS in Endocrinology & Metabolism ratios (HRs) and o (e.g., those consum Figure 1. Beverage consumption and the prevalence of obesity. Line graph illustrates Trends in Endocrinology and M etabolism 013, Vol. 24, Ncom o. bolic 2syndrome changes in per capita consumption of artificially sweetened beverages (ASB; red September Estudios de Cohorte Prospectivos/ observacionales Dietary Intake and the Development of the Metabolic Syndrome The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study Pamela L. Lutsey, MPH; Lyn M. Steffen, PhD, MPH, RD; June Stevens, PhD, MS, RD • “… Diet Soda también se asoció positivamente con la incidencia de SM. Aquellos en el tercil más alto de consumo con 34% mayor riesgo que el tercil más bajo. La fuerza de esta asociación es sorprendente. Sin embargo es consistente con datos recientes del Estudio Framingham, que encontró 56% aumento del riesgo de SM entre quienes consumían una porción de diet soda por día…” ackground—The role of diet in the origin of metabolic syndrome (MetSyn) is not well understood; thus, we sough evaluate the relationship between incident MetSyn and dietary intake using prospective data from 9514 participants (a 45 to 64 years) enrolled in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC)Intake study. and the Development o Dietary ethods and Results—Dietary intake was assessed at baseline via a 66-item food frequency Syndrome questionnaire. We u Metabolic principal-components analysis to derive “Western” and “prudent” dietary patterns from 32Risk foodingroups and evalua The Atherosclerosis Communities St 10 food groups used in previous studies of the ARIC cohort. MetSyn was defined by American Heart Associat Pamela L. Lutsey, MPH; Lyn M. Steffen, PhD, MPH, RD; June Steven guidelines. Proportional-hazards regression was used. Over 9 years of follow-up, 3782 incident cases of MetSyn w Background—The role of diet in the origin of metabolic syndrome (MetSyn) is not well un identified. After adjustment for demographic factors, smoking, physical activity, and energy intake, consumption o evaluate the relationship between incident MetSyn and dietary intake using prospective data 45 to 64with years) incident enrolled in the Atherosclerosis Riskfurther in Communities (ARIC) study. Western dietary pattern (Ptrend!0.03) was adversely associated MetSyn. After adjustment for int Methods and Results—Dietary intake was assessed at baseline via a 66-item food freque of meat, dairy, fruits and vegetables, refined grains, and whole grains, analysis of individual groups revealed principal-components analysis to derive “Western” and food “prudent” dietary patterns from 3 10 food groups used in previous studies of the ARIC cohort. MetSyn was defined meat (Ptrend"0.001), fried foods (Ptrend!0.02), and diet soda (Ptrend!" 0.001) also were adversely associatedbyw guidelines. Proportional-hazards regression was used. Over 9 years of follow-up, 3782 in incident MetSyn, whereas dairy consumption (Ptrend!0.006) was No associations were observed betw identified. Afterbeneficial. adjustment for demographic factors, smoking, physical activity, and ene Western dietary pattern (P !0.03) was adversely associated with incident MetSyn. After incident MetSyn and a prudent dietary pattern or intakesof of whole grains, refined grains, fruits and vegetables, n meat, dairy, fruits and vegetables, refined grains, and whole grains, analysis of individu meat (P "0.001), fried foods (P !0.02), and diet soda (P !" 0.001) also wer coffee, or sweetened beverages. incident MetSyn, whereas dairy consumption (P !0.006) was beneficial. No associat onclusions—These prospective findings suggest that consumption ofanda aWestern dietary meat,grains, andrefined friedgrains fo incident MetSyn prudent dietary pattern orpattern, intakes of whole coffee, orprovides sweetened beverages. promotes the incidence of MetSyn, whereas dairy consumption some protection. The diet soda association w Conclusions—These prospective findings suggest that consumption of a Western dietary p not hypothesized and deserves further study. (Circulation. 2008;117:754-761.) promotes the incidence of MetSyn, whereas dairy consumption provides some protection. T trend trend trend trend trend not hypothesized and deserves further study. (Circulation. 2008;117:754-761.) Key Words: dairy products ! diet ! food habits Key metabolic syndrome ! meat Words:! dairy products ! diet ! food habitsX! meat ! metabolic s O R I G I N A L A R T I C L E Diet Soda Intake and Risk of Incident Metabolic Syndrome and Type 2 Diabetes in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Diet Atherosclerosis Soda Intake and Risk of In (MESA)* Metabolic Syndrome and Type Nettleton and Associates residual confounding by other dietary beJ A. N , J A. L , in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Ath E D. M , haviors, lifestyle factors, or demographic P L. L , Table 2—Risk of incident metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes according to diet soda consumption categories in participants from MESA Y W , D R. J , J ., characteristics (1,2). Biological mecha(MESA)* nisms possibly explaining these associaCardiovascular and Metabolic Risk O R I G I N A L ENNIFER AMELA OUFA ETTLETON PHD 2 UTSEY PHD 3 ANG MD, PHD 1 OÃO RIN AVID A R T I C L E 4 IMA PHD 4 ICHOS MD ACOBS R PHD 2,5 tions are few and largely focus on artificial # rare/never but !1 !1 serving/week to !1 increasing in beverages/foods OBJECTIVE — We determined associations between diet soda consumption and riskJENNIFER of sweeteners A. NETTLETON , PHD1 JOÃO A. LIMA, PHD4 Rare or never serving/week serving/day !1 serving/day 4 2 of) incident metabolic syndrome, its components, and type 2 diabetes in the Multi-Ethnic Study of the RIN D. MICHOS, MD PAMELA L. Ldesire UTSEY, for PHD (and consumption E Atherosclerosis. Ptrend* YOUFA sugar-sweetened, WANG, MD, PHD3 energy-dense beveragDAVID R. JACOBS, JR., PHD2,5 Metabolic syndrome es/foods (3) or disrupting consumers’ RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS was assessed by food ability to accurately n 2,288 — Diet soda consumption367 722 estimate energy in- 501 frequency questionnaire at baseline (2000 –2002). Incident type 2 diabetes was identified at take and remaining energy needs (4). Cases 478 95 169 129 OBJECTIVE — We determined associations between diet soda consumption and risk of three follow-up examinations (2002–2003, 2004 –2005, and 2005–2007) as fasting glucose Thus, diet soda consumption may result incident metabolic syndrome, its components, and type 2 diabetes in the Multi-Ethnic Study of !126 type 2 diabetes,1.00† or use of diabetes medication. Metabolic syndrome HRmg/dl, (95%self-reported CI) 1.34 (1.07–1.67) 1.20 (1.00–1.43) 1.31 (1.07–1.60) 0.003 in overconsumption, increased body Atherosclerosis. (and components) was defined by National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment 1.00‡ 1.42 (1.14–1.78) 1.28 (1.06–1.53) 1.36 (1.11–1.66) !0.001 Panel III criteria. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CI for type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and weight, and consequent metabolic dysRESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS — Diet soda consumption was assessed 1.00§ adjusting for1.31 (1.05–1.64) 1.13 (0.94–1.37) 0.06 by food If true, such relations 1.18 have (0.96–1.44) metabolic syndrome components were estimated, demographic, lifestyle, and function. frequency questionnaire at baseline (2000 –2002). Incident type 2 diabetes was identified at important implications for dietary coundietary confounders. 1.00! 1.30 (1.04–1.62) 1.15examinations (0.95–1.38) 1.17 (0.96–1.44) 0.06 three follow-up (2002–2003, 2004 –2005, and 2005–2007) as fasting glucose seling, given the high frequency of diet Type 2 diabetes !126 mg/dl, self-reported type 2 diabetes, or use of diabetes medication. Metabolic syndrome RESULTS — At least daily consumption of diet soda was associated with a 36% greater relative beverage consumption by those at high (and components) was by National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment 455 type 2 diabetes 914defined 681 risknof incident metabolic syndrome 2,961 and a 67% greater relative risk of incident risk for metabolic dysfunction (5). Panel III criteria. Hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CI for type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and compared and Cases with nonconsumption (HR 1.36 221 [95% CI 1.11–1.66] for metabolic 33 syndrome metabolic 84 75 for demographic, lifestyle, and Replication of previously observedadjusting syndrome components were estimated, 1.67 [1.27–2.20] for type 2 diabetes). Of metabolic syndrome components, only high waist soda–metabolic HR (95%(men CI) !102 cm and women !88 1.00† 1.06 (0.73–1.52) 1.39 (1.07–1.80)syndrome associa1.63 (1.24–2.13) !0.001 dietary diet confounders. circumference cm) and high fasting glucose (!100 mg/dl) were tions in a distinct cohort would bolster prospectively associated with diet soda consumption. between diet soda consump1.00‡ Associations1.10 (0.76–1.59) 1.46 (1.12–1.89) 1.67 (1.27–2.20) !0.001 RESULTS At least daily of diet soda their—credibility andconsumption provide further in- was associated with a 36% greater relative tion and type 2 diabetes were independent 1.00§ of baseline measures of1.00 adiposity or changes in these (0.69–1.45) (0.94–1.60) (1.06–1.84) 0.01 risk of incident metabolic syndrome a 67%1.40 greater relative risk of incident type 2 diabetes sight1.23 into the nature of theand relationship. measures, whereas associations between diet soda and metabolic syndrome were not indepencompared with nonconsumption (HR 1.36 [95% CI 1.11–1.66] for metabolic syndrome and 1.00! 0.98 (0.68–1.42) 1.25 (0.96–1.62) 1.38 (1.04–1.82) 0.01 Previous studies have not addressed assodent of these factors. Los sujetos en el percen.l más alto de consumo de diet soda tenían mayor IMC y circunferencia de cintura basales 1.67 [1.27–2.20] for type 2 diabetes). Of metabolic syndrome components, only high waist between dietrace/ethnicity, soda and individual n " 5,011. *Ptrend with categorical variable modeled continuously. †Model 1 adjusted forciations study(men site, age, sex, ‡Model(!100 2 adjusted circumference !102 cm and women !88and cm) energy and highintake. fasting glucose mg/dl) were CONCLUSIONS — Although these observational data cannot establish causality, consumpmetabolic syndrome components or risk for the variables in model 1 above plus education, physical activity, smoking status,prospectively pack-years,associated and weekly ordiet more supplement use. §Adjustedbetween for thediet variables in with soda consumption. Associations soda consumption of diet soda at least daily was associated with significantly greater risks of select incident of type 2 diabetes nor have they fully admodel 2 above $ waist circumference (centimeters). !Adjusted for the variables in model 2 above $ waist circumference (centimeters) and BMI (weight in kilograms tion and type 2 diabetes were independent of baseline measures of adiposity or changes in these metabolic syndrome components and type 2 diabetes. dressed potential longitudinal mediators measures, whereas associations between diet soda and metabolic syndrome were not independivided by the square of height in meters). these relationships, i.e., changes in addent of of these factors. Diabetes Care 32:688–694, 2009 iposity status (body weight and or waist CONCLUSIONS thesewe observational 2 — Although circumference). Therefore, evaluated data cannot establish causality, consump4.51] with considBMI If excludedcohort fromstudies our analyses parMetabolic syndrome and wowe longitudinal have such as diet1.10 soda,–are commonly tion!25 of associations diet kg/m soda at least daily was with significantlycomponent greater risks of select incident between diet associated soda consump2 ticipants with any metabolic syndrome Compared with metabolic syndrome type 2 diabetes. 1.48 [1.07–2.05] with !25 shown positive associations be- ered “benign” because they contribute noBMI tion and kg/m riskcomponents of )incidentand metabolic syn- nonconsumers, individtween dietatsoda consumption and a energy few nutrients diet. Concomponent baseline (leaving muchandand uals consuming drome (and metabolic syndrome !1 daily serving of diet for typeto2the diabetes (1.94 [0.87– 4.35] Diabetes Care 32:688–694, 2009 incident metabolic syndrome indepensequently, the previously observed diet 2 components) as well soda as incident 2 smaller sample of 1,078 participants and had atype significantly greater risk of de- T re ha ch ni tio sw th su es ab ta Th in w fu im se be ri di tio th si Pr ci m of dr of ip Causalidad Reversa?? Confundentes Residuales?? • Podría ser el consumo de diet soda un marcador de otros estilos de vida poco saludables o a algún patrón alimentario que derive en riesgo metabólico?? REVIEW Does low-energy sweetener consumption affect energy intake and body weight? A systematic review, including metaanalyses, of the evidence from human andLow-energy animalsweeteners studies systematic review PJ Rogers et al PJ Rogers1, PS Hogenkamp2, C de Graaf3, S Higgs4, A Lluch5, AR Ness6, C Penfold6, R Perry6, P Putz7, MR Yeomans8 and DJ Mela9 By reducing energy density, low-energy sweeteners (LES) might be expected to reduce energy intake (EI) and body weight (BW). To assess the totality of the evidence testing the null hypothesis that LES exposure (versus sugars or unsweetened alternatives) has no effect on EI or BW, we conducted a systematic review of relevant studies in animals and humans consuming LES with ad libitum access to food energy. In 62 of 90 animal studies exposure to LES did not affect or decreased BW. Of 28 reporting increased BW, 19 compared LES with glucose exposure using a specific ‘learning’ paradigm. Twelve prospective cohort studies in humans reported inconsistent associations between LES use and body mass index (−0.002 kg m−2 per year, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.009 to 0.005). Meta-analysis of short-term randomized controlled trials (129 comparisons) showed reduced total EI for LES versus sugarsweetened food or beverage consumption before an ad libitum meal (−94 kcal, 95% CI −122 to −66), with no difference versus water (−2 kcal, 95% CI −30 to 26). This was consistent with EI results from sustained intervention randomized controlled trials (10 comparisons). Meta-analysis of sustained intervention randomized controlled trials (4 weeks to 40 months) showed that consumption of LES versus sugar led to relatively reduced BW (nine comparisons; −1.35 kg, 95% CI –2.28 to −0.42), and a similar relative reduction in BW versus water (three comparisons; −1.24 kg, 95% CI –2.22 to −0.26). Most animal studies did not mimic LES consumption by humans, and reverse causation may influence the results of prospective cohort studies. The preponderance of evidence from all human randomized controlled trials indicates that LES do not increase EI or BW, whether compared with caloric or non-caloric (for example, water) control conditions. Overall, the balance of evidence indicates that use of LES in place of sugar, in children and adults, leads to reduced EI and BW, and possibly also when compared with water. International Journal of Obesity (2016) 40, 381–394; doi:10.1038/ijo.2015.177 INTRODUCTION Low-energy sweeteners (LES), such as acesulfame-K, aspartame, saccharin, stevia and sucralose are consumed throughout the world.1 The history of their use has been accompanied by debate and disagreements, not least about their potential nutritional impact. The use of LES to replace or partially replace added sugar in foods and beverages might well be expected to reduce energy intake (EI),2–4 yet over recent years there has been widely reported speculation that consumption of LES might increase the risk of becoming overweight and obese.5–7 Studies covertly manipulating energy density show higher EI after consumption of a reduced-energy food or beverage, but that the degree of energy ‘compensation’ is variable.8 Crucially, energy compensation is usually lower than the difference in energy content of the comparison foods/beverages, seemingly being lowest of all for liquids.8 This suggests that consuming LES in place of sugar-sweetened products should reduce overall EI, and particularly so for consumption of beverages, the most popular OPEN vehicles for LES.1 The question also arises whether the presence of LES in beverages affects appetite and EI relative to plain water.1,9 Although the imprecise control of short-term energy balance predicts that LES consumption should help reduce EI and therefore reduce risk of overweight and obesity,3,10 it is possible that, as consumed in everyday life, other effects of LES balance or even outweigh the energy dilution effect. For example, a low calorie or ‘diet’ label may cause the consumer to eat a larger portion of the product or eat more of accompanying foods in the meal, or eat more later.11–14 More simply, adding sweetness to a product may increase intake owing to increased palatability.15,16 Or, by ‘uncoupling’ the relationship between sweetness and energy content, the consumption of LES may undermine the usefulness of sweetness as a cue in the control of energy balance.5,17–20 The effects of LES consumption on EI and body weight (BW) have been the subject of many studies over the past 30 years; nonetheless there is no clear consensus about this body of evidence. Taken together, a number of narrative reviews1–4,21–25 and systematic reviews of some types of studies26–30 lead to the International Journal of Obesity (2016) 40, 381–394 consistent but guarded conclusion that substitution of LES for © 2016 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0307-05 sugar, especially in beverages, can help reduce EI, but that fully orest plot showing individual and combined effect sizes for prospective cohort studies reporting the association betw n and change in BMI over the follow-up period. Effect sizes have been standardised to a 1 year follow-up period. Negativ Placer por lo dulce, azúcar y obesidad Edulcorantes artificiales: no tan rápido! Buscando Causalidad: Plausibilidad Biológica Evidencia actual Conclusiones – El hecho de agregar sabor a un “vehículo” no calórico podría aumentar el apetito posterior. – Estudios no han demostrado efectos en apetito cuando edulcorantes se han administrado a través de SNG o en cápsulas Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:1–14. Hambre, Apetito y Saciedad Respuestas Digestivas Preabsortivas El sabor dulce de la sacarina promovería una aumento del hambre e ingesta a través de esKmulación de secreción de insulina (preabsorKva) Efectos Nutritivos y Osmóticos Bebidas con mayor densidad energéKca u osmolaridad son vaciadas más lentamente del estómago Hambre, Apetito y Saciedad Respuesta de Péptidos Intestinales • Macronutrientes en la dieta estimulan la liberación de péptidos intestinales. • CH estimula secreción de GLP-1, potente incretina y factor de saciedad Am J Clin Nutr 2009;89:1–14. Aumento de ingesta y Balance Uso informado produciría sobrecompensación Disrupción del aprendizaje de asociación Placer por lo dulce, azúcar y obesidad Edulcorantes artificiales: no tan rápido! Mecanismos propuestos para el “daño” Evidencia actual Conclusiones F Bellisle and A Drewnowski 694 Estudios de “precarga” Table 3 The impact of intense sweetener aspartame on hunger and energy intakes compared to the control conditions Study Subjects Dose (mg) Volume (ml) Vehicle Control condition(s) Delay (min) Meal Hunger Consumption Blundell and Hill (1986) Rogers et al. (1988) 95 8M, 4F 162 162 200 200 Water Water — 60 — Lunch Birch et al. (1989) Rodin (1990) 24 (4–5 years) 140 24 250 205 500 Fruit drink Water 0–60 38 Snacks Lunch Increased Higher No effect — — — No No No No Rolls et al. (1990) 42M 0,30, 60 Lunch Decreased No effect 20 M Soft drink Water 60 Lunch No effect No effect Canty and Chan (1991) 2M, 18F 240 480 280 560 200 Lemonade Black et al. (1991) 110 220 160 320 112 Water Water Glucose Water Water Fructose Glucose Water Fruit drink 60 Lunch Black et al. (1993) 18M 340 280 560 65 Lunch No effect No effect No effect No effect No effect No effect DiSogra et al. (1990) 6M, 6F 10M, 5F Water Water 60 60 Lunch Lunch Tordoff and Alleva (1990a) Anderson et al. (1989) Rolls et al. (1989) 60M, 60F 234 235 470 0.05–1% Capsule Water Soft drink Capsules Capsules Water Sucrose Water — — Decreased Decreased Decreased — 20 (9–10 years) 10 mg/kg 16M, 16F 211–391 300 Ad lib 90 120 Lunch Lunch — Decreased Decreased Higher Higher No effect No effect No effect No effect Mattes (1990a) 12M, 12F 70g 180 Drewnowski et al. (1994b) 12M, 12F 0.16% by weight 500 Decreased Decreased No effect No effect No effect No effect Drewnowski et al. (1994b) 24F 500 500 No effect No effect Lavin et al. (1997) 14F Not reported 330 No effect No effect Increased No effect Beridot-Therond et al. (1998) 12M, 12F 50 mg/l Ad lib B15 B6.5hr No effect No effect Melanson et al. (1999b) 10M B100 350 Variable Lunch — No No No No King et al. (1999) 16M Not reported 790 Water Unsweetened Sucrose Lemon Water Carbohydrate Fat Fruit drink Water Lunch Dinner Lunch Snack Dinner Lunch Snack Dinner Snack Lunch Dinner Lunch Dinner B15 Lunch No effect Increased Wilson (2000) 135 (2–5 years) Not reported Ad lib Milk Sucrose Milk 0 Lunch No effect — Increased No effect Van Wymelbeke et al. (2004) 12M, 12F 2000 Fruit drink Sucrose milk Sucrose Varibale Lunch No effect Dinner 40 — 500 Chewing gum Plain gum No gum Fruit drink Sucrose Pudding/ Sucrose Gelatin Cereal Plain Sucrose Soft white Plain cheese Sucrose Maltodextrin Soft white Plain cheese Sucrose Maltodextrin Lemonade Sucrose Water Fruit drink 3h 6.5h 9.5h 3h 6.5h 9.5h Variable effect effect effect effect effect effect effect effect No effect No effect Adelaide Hospital, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 5000 Australia. and GIP, the so-called incretin hormones, from the gut in healthy E-mail: chris.rayner@adelaide.edu.au. humans (3). In patients with type 2 diabetes, the incretin effect is 4 Abbreviations used: GIP, glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide; impaired (4). Incretin-based therapies for diabetes have focused GLP-1, glucagon-like peptide 1; iAUC, incremental AUC; SGLT1, sodiumon GLP-1 rather than on GIP, because the insulinotropic action glucose cotransporter-1; T50, half-emptying time; TIM, tagatose/isomalt mix1–3 of the latter is diminished in these patients (5). Other actions of ture; 3OMG, 3-O-methyglucose. GLP-1 include slowing of gastric emptying (6) and reduction of Received June 11, 2011. Accepted for publication October 11, 2011. published online December 7, 2011; doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.021543. energy intakeJ(7). Tongzhi Wu,appetite Beiyi Rand Zhao, Michelle Bound, Helen L Checklin, Max Bellon, First Tanya J Little, Richard L Young, Karen L Jones, Michael Horowitz, and Christopher K Rayner Effects of different sweet preloads on incretin hormone secretion, gastric emptying, and postprandial glycemia in healthy humans 78 Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:78–83. Printed in USA. ! 2012 American Society for Nutrition ABSTRACT One promising strategy to stimulate endogenous GLP-1 is the Background: Macronutrient “preloads” can stimulate glucagon“preload” concept, in which a small load of macronutrient is given like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypepa fixed interval before a meal, to induce the release of gut peptides tide (GIP), slow gastric emptying, and reduce postprandial glycemic such as GLP-1 and GIP to slow gastric emptying and stimulate excursions. After sweet preloads, these effects may be signaled by insulin secretion in advance of the main nutrient load. We have sodium-glucose cotransporter-1 (SGLT1), sweet taste receptors,Appetite or shown both fat and protein preloads markedly reduce post55 (2010)that 37–43 both. prandial glycemic excursions in patients with type 2 diabetes by Objective: We determined the effects of 4 sweet preloads on GIP these mechanisms (8, 9). However, a potential disadvantage is that Contents lists available at ScienceDirect and GLP-1 release, gastric emptying, and postprandial glycemia. the preload could increase overall energy intake; preloads that Design: Ten healthy subjects were studied on 4 separate occasions entail minimal additional energy would be advantageous. each. A preload drink containing 40 g glucose, 40 g tagatose/isoIncretin stimulation by carbohydrates may be signaled by Appetite malt mixture (TIM), 40 g 3-O-methylglucose (3OMG; a nonmetasweet taste receptors and/or SGLT1. Data from in vitro, animal, bolized substrate of SGLT1), or 60 mg sucralose was consumed 15 and human studies in this area have been inconsistent. For example, j o u r n apotato l h o mmeal. e p a gBlood e: www.elsevier.com/locate/appet min before a 13C-octanoic acid–labeled mashed stimulation of sweet taste receptors by sucralose (a noncaloric glucose, plasma total GLP-1 and GIP, serum insulin, and gastric artificial sweetener) was reported to release GLP-1 from enteroemptying were determined. endocrine L cells in vitro (10, 11) but has no effect on GLP-1 Research report Results: Both glucose and 3OMG stimulated GLP-1 and GIP resecretion and gastric emptying in humans (12). It has also been lease in advance of the meal (each P , 0.05), whereas TIM and postulated that intake, SGLT1 maysatiety, be involved and in incretin hormone seEffects and sucrose on food postprandial sucralose did of not.stevia, The overallaspartame, postprandial GLP-1 response was cretion (13). Monosaccharides that are substrates for SGLT1, in§ greater after glucose, and TIM than after sucralose (P , glucose and3OMG, insulin levels cluding glucose, galactose, and 3OMG, stimulate GLP-1 release in 0.05), albeit later after TIM than the other preloads. The blood vitro anda in perfused ileum in aanimal studies (14–16), ana effect a,b,d, a glucose and insulin responses in*the first 30 min after the meal were , Corby K. Martin Stephen D. Anton , Hongmei Han by , Sandra , William T. Cefalu inhibited phloridzin,Coulon which blocks SGLT1 (13). Similarly, ,in ob/ a,cP , 0.05). Gastric emptying was aslower greatest glucose (each , Donald A. Williamson Paulaafter Geiselman ob mice, GIP is37–43 secreted in response to glucose, galactose, and Appetite 55 (2010) after both 3OMG and TIM than after sucralose (each P , 0.05). a 3OMG (17), but not to fructose and mannose, which are not Pennington Biomedical Research Center, Baton Rouge, LA, United States Conclusions: In healthy humans, SGLT1 substrates stimulate GLP-1 b Department of Aging and Geriatric Research, University of Florida, United States SGLT1 substrates (18, 19). 3OMG is a glucose analog that is aband GIP and slow gastric emptying, regardless of whether they are lists available at ScienceDirect c Contents Department of Psychology, Louisiana State University, United States sorbed from the small intestine via SGLT1, but it is not metabod metabolized, whereas the artificial sweetener sucralose does not. Institute on Aging, University of Florida, 210 E Mowry Rd., Gainesville, FL 32611, United States lized and makes no contribution to energy intake. Whether 3OMG Poorly absorbed sweet tastants (TIM), which probably expose stimulates GIP and GLP-1 secretion in humans is unknown. a greater length of gut to nutrients, result in delayed GLP-1 secretion but A Rnot T Iin C delayed L E I N FGIP O release. These observations A B have S T Rthe A Cpotential T 1 to optimize the use of preloads for glycemic control. This trial was From the Discipline of Medicine, University of Adelaide, Royal Adejournal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/appet Article history: Consumption of Am sugar-sweetened beverages may Australia be one of(TW, the dietary causes of metabolic disorders, laide Hospital, Adelaide, BRZ, MJB, HLC, TJL, KLJ, MH, registered at www.actr.org.au as ACTRN12611000775910. J Received 30 September 2009 such as obesity. Therefore,and substituting sugar with low calorie sweeteners may(MB) be anand efficacious weight CKR), and the Department of Nuclear Medicine the Nerve Clin Nutr 2012;95:78–83. Downloaded from ajcn.nutrition.org by guest on May 3, 2016 • No hubo incremento de niveles de insulina después de la carga de sucralosa ni de tagatosa a diferencia de glucosa • No hubo incremento de los niveles de GLP-­‐1 después de carga de sucralosa • No hubo diferencia significaKva en el Kempo de vaciamiento gástrico después de la carga de sucralosa o glucosa • La sensación de saciedad fue mayor después de la carga de glucosa que sucralosa, sin embargo no hubo diferencias en apeKto ni en ingesta posterior • Menor aumento de glucosa post carga de stevia y aspartame en relación Appetite a sacarosa • Menor aumento de insulina post carga de stevia en relación a aspartame y sacarosa Gut Laboratory (RLY), Royal Adelaide Hospital, Adelaide, Australia. Research report Supported by a grant awarded by the National Health and Medical ReINTRODUCTION search Council (NHMRC) of Australia (grant no. 627139). TJL was sup• Sin d iferencias e n a peKto n i i ngesta posterior MajorEffects determinants postprandial blood glucose include ofofstevia, aspartame, andthesucrose on food intake, satiety, and postprandial Received in revised form 1 December 2009 Accepted 10 March 2010 management strategy. We tested the effect of preloads containing stevia, aspartame, or sucrose on food 2 intake, satiety, and postprandial glucose and insulin levels. Design: 19 healthy lean (BMI = 20.0–24.9) and 12 obese (BMI = 30.0–39.9) individuals 18–50 years old completed three separate food test days Keywords: during which they received preloads containing stevia Clinical (290 kcal), aspartame (290 kcal), or sucrose ported by an NHMRC Overseas Postdoctoral Training Fellowship Stevia (493 kcal) before the and dinner meal. The preload order was balanced, and food intake (kcal) was no. 519349). rate of gastric emptying (1, 2) and the postprandial re-lunch(grant §insulin Aspartame 3 4 directly calculated. Hunger and satiety levels were reported beforeDiscipline and afterofmeals, and Royal every hour Address correspondence to CK Rayner, Medicine, Sucrose of which !50% is stimulated by the secretion of GLP-1 sponse, throughout the afternoon. Participants provided blood samples immediately before and min after the FoodGIP, intake Adelaide Hospital, North Terrace, Adelaide, South Australia 500020 Australia. and the so-called incretin hormones, from the gut in healthy a,b,d, a a in preloads (290 kcal a lunch preload. Despite the caloric difference vs. 493 kcal), participants dida not glucose and insulin levels RCT Largo Plazo Intense sweeteners, energy intake and the control of body weight F Bellisle and A Drewnowski 69 Table 4 Long-term studies of the impact of intense sweetener aspartame on body weight Study Subjects Design Period Weight loss diet Products Body weight loss Tordoff and Alleva (1990b) 21M,9F Normal wt. Xover 3 ! 3 weeks No 0.5 kg loss M, F Kanders et al. (1988) 13M,46F Obese 2arm 12 weeks Yes Soda, 1150 g reg. or diet (aspartame) Aspartame vs not Blackburn et al. (1997) 163F Obese 2arm 19 weeks þ 1 year Yes Aspartame vs not Raben et al. (2002) 6M,35F 2arm 10 weeks No Sucrose vs Aspartame Aspartame lost, sucrose gained Porikos et al. (1977) Overwt. 6F, 2M Obese Xover 3 ! 6 ! 6 days No Sucrose vs Aspartame No change All lost, non-Asp F lost least Both lost B10%, Asp regained less Asp ¼ Aspartame. reduction in sugar intake. On the other hand, Bellisle et al. 1977, 1982; Tordoff and Alleva, 1990b; Kanders et al., 1990; Tate J F / 2012) 318 a dultos 2 b razos + 6 m eses No and Cambio de b1995; ebidas Blackburn regulares et al., Sin diferencias (2001) found, in a cohort of 4278 French adults, aged 45–60 Naismith Rhodes, 1997; Gatenby sobrepeso y control por d iet o a gua -­‐2% d el p eso years, that about 30% of women and 22% of men were at et al., 1997; Reid and Hammersley, 1998; Raben et al., 2002). obesos least occasional users of intense sweeteners. As expected, These RCTs showed considerable variations in their design, higher body mass index (BMI) values and higher waist/hip study population, duration and type of control. In addition, Peters JC (2014) 303 adultos 2 brazos 12+40 semanas Si 24 onzas de diet soda/24 onzas -­‐5.95 kg asp, ratios were associated with more frequent use, suggesting certain studies compared dietary conditions that did not sobrepeso y de agua por día menos hambre that overweight persons were using intense sweeteners as a only differ by the presence or absence of intense sweeteners. obesos -­‐4.09 kg agua strategy for weight control. Users had lower energy intakes For example the Foltin et al. (1988, 1992) studies did not (significant difference in men only) and consumed less focus specifically on intense sweeteners but compared diets carbohydrate than did nonusers. In a Spanish study of 2450 varying in fat as well as carbohydrate contents, thereby persons (Serra-Majem et al., 1996), about 18% of the making it impossible to single out the contribution of population used cyclamate. Within the user group, higher sweeteners in the reported effects. The meta-analysis re- a 12-week loss treatment program. treatment but was not significantly difWing examined the use of NNS beveragesduring by those in the behavioral National weight a function of the behavioral Methods: An equivalence trial design with water or NNS beverages as the main factor in a prospective Weight Control Registry and found that successful weight losers ferent between groups. Sedentary behavior actually decreased signifrandomized trial among 303 men and women was employed. All participants participated in a behavioral drank three times the NNS beverages compared to those who had icantly in the Waterweight grouploss overphase time (12 but weeks) not theofNNS group. The weight loss treatment program. The results of theBeverages an ongoing trial (1 The Effects of Water and Non-Nutritive Sweetened never lost weight (24). changes time two weretreatments not significant between groups. Taken year) that is also evaluating the effectsover of these on weight loss maintenance were together, changes in physical activity and sedentary behaviors cannot on Weight Loss During areported. 12-week Weight Loss Treatment We chose 12 weeks as the weight loss phase because mosttreatments studies were account for the difference weight loss observed. Results: The two not equivalent with the in NNS beverage treatment group losing signifiProgram weightofcompared show that weight loss slows considerablycantly after more 6 months treat- to the water group (5.95 kg versus 4.09 kg; P < 0.0001) after 12 weeks. 1 2 occurring in 1theNNS 2on reported 2 Participants beverage group greater subjective feelings ment with more thanR.half of1,the weight loss inthe firstC. 12Wojtanowski Based the design of thisVeur study are unablein to say, what is theof John C. Peters , Holly Wyatt Gary D. Foster , Zhaoxing Pan , Alexis , Stephanie S.significantly Vander , wereductions 2 1 1 hunger than those in the water group during 12 weeks. weeks (25,26), probably owing to difficulty with longer term adhermechanism for the greater weight loss in the NNS group compared Sharon J. Herring , Carrie Brill and James O. Hill Conclusion: These results show that water water group. is not superior NNS beverages for significantly weight loss during ence to a hypocaloric regimen. Furthermore, it is now recognized to the Weekly tohunger scores were lower a comprehensive behavioral weight loss program. that weight loss is a different process from weight maintenance, among the NNS group than the water group although the absolute Objective: To compare efficacy of non-nutritive sweetened or water for weight lossit is plausible that the NNS participants 22, 1415–1421. doi:10.1002/oby.20737 both behaviorally and the physiologically, soObesity it is(2014) important tobeverages study (NNS) changes were small. While during a 12-week behavioral weight loss treatment program. treatment effects on these two processes separately (27). The benefit were more likely to adhere to the dietary recommendations due to Methods: An equivalence trial design with water or NNS beverages as the main factor in a prospective of the current 1 year trial is that we will be able to compare both less hunger than the Watera beneficial group we cannot conclude this based and on energy effect or no effect of NNS on appetite randomized trial among 303 men and women was employed. All participants participated in a behavioral Introduction weight and weight loss maintenance within same study. Some authors (3,5,6)Other havestudies suggested that use of of NNS have reported findings increased weight loss loss treatment program. The results Beverage of the the weight lossgroup phaseof(12 this weeks) of an ongoing trial (7-11). (1 consumption recommendations (1) suggest water as the with consumption ofand NNS disrupt (11) but generally withoutofan acco participants. The trial was designed to allow preplanned analysis of may increase appetite for sweet foods regulation year) that is also evaluating the effects ofgold-standard these twobeverage treatments on weight lossUSmaintenance for optimal health. The Dietary Guide- were ing increase in caloric intake. the treatment effects after just the 12-week weight phasebeverages as energy balance.sweeteners Weight loss results for the present study suggest lines (2) suggestloss that while with non-nutritive reported. (NNS) are preferable to those with caloric there is still a did not increase energy intake from other well as after months of weight (still which that sweeteners, NNSgroup consumption Results: The 9two treatments weremaintenance not equivalent withunderway) the NNS beverage treatment losing signifiquestion about whether they are beneficial for weight management. Several observational studies have reported a positive asso will bemore reported separately. foods compared to12water. This isNNS consistent with that cantly weight compared to the water group (5.95 kg versus 4.09 kg; P < 0.0001) after weeks. between consumption and other greater studies body weight and weig While numerous clinical trials have examined the effects of nutritive over time (4,12). Determining causality is not possible wit Participants in the NNS beverage group reported significantly greater reductions in subjective feelings of have not found increased consumption of sweet or high energy sugar sweetened beverages (NS) compared to NNS beverages on studies but it is possible that they represent “reverse ca weight loss, few studies have directly compared water and NNS hunger than those in the water group during 12 weeks. While most secondary outcomes were not different between the foods while using NNS (28,29). Further studies will be needed to obesity may cause people to seek diet beverages (10 on weight to lossNNS usingbeverages an equivalence design.loss duringwhereby Conclusion: These group results showed show that waterbeverages is not superior fortrial weight groups, the NNS greater reductions in totaland ascertain the mechanism(s)athat may be responsible for the weight comprehensive behavioral weight losstoprogram. LDL-cholesterol. This may be due the NNS greater loss thefood loss wereweight introduced intointhe supplyresults. over 50 years ago and The largest and most recent randomized trial (14) to compare • Objetivo: comparar la eficacia de ENC o agua para la pérdida de peso durante un programa de tratamiento de obesidad • 303 adultos obesos de ambos sexos, todos participaron del programa de manejo conductual. • Al grupo ENC se le pidió consumir al menos 24 onzas de bebidas con ENC por día+ consumo libre de agua • Al grupo agua, se le pidió consumir al menos 24 onzas de agua por día y no diet beverages and an attention control for their effects on being used of different food and beverage products. consumir ni agregar are ENC enin hundreds cualquier producto líquido. Sí podían consumir Despite the long history of usage there continues to be considerable loss used a superiority trial design. The authors found that otros alimentos con controversy ENC. concerning their role in the diet, particularly whether beverage treatment, but not water, significantly increased the they are a useful tool as an aid in weight loss and weight loss main- bility of losing 5% of body weight over the 6-month study d Obesity (2014) 22, 1415–1421. doi:10.1002/oby.20737 Introduction tenance (3-6). NNS provide sweetness equivalent to NS but contrib- compared to a standard weight loss education and monitori TABLE 3 Absolute weight loss (kg) for completers (7-11). Other studies have reported findings of increased hunger a beneficial effect or no effect of NNS on appetite and energy intake essentially energy. Since the 1980s a number of short-term gram. Subjects in both treatment groups lost a significant am Beverage consumption recommendations (1) suggestute water as the zero with consumption of NNS (11) but generally without an accompanyexperimental have compared NNS to NS and several com- weight but the amount of weight lost compared to the cont gold-standard beverage for optimal health. The US Dietary Guide-studies ing increase in caloric intake. Baseline Week 90% CL mean between treatment groups. P value prehensive reviews 12 haveclinic concluded that the evidence supports either not different lines (2) suggest that while beverages with non-nutritive sweeteners Group (kg) (kg) Change for change for change (NNS) are preferable to those withweight caloric sweeteners, there is still weight a Several observational studies have reported a positive association 1 question about whether they are beneficial for weight management. Anschutz Health and Wellness Center, University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO, USA. Correspondence: John C. Peters between NNS consumption and greater body weight andand weight gain Department 2 Temple University, Center for Obesity Research Education, PA, USA While(nnumerous examined the effects(john.c.peters@ucdenver.edu) of nutritive87.11 NNS 5 142)clinical trials have93.56 (13.23) (12.85) 26.45 (3.68)* 25.94, 26.96 of Medicine, Philadelphia, <0.0001 over time (4,12). Determining causality is not possible with these sugar sweetened beverages (NS) compared to NNS beverages on Water (n 5 134) 93.88 (12.99) Funding Agencies: 89.33 (13.07) 24.55 (3.67)* 24.03, 25.08 <0.0001 studies but fully it funded is possible that theyBeverage represent “reverse causality” study was by The American Association. weight loss, few studies have directly compared water and NNS The whereby obesity may causeThe people to(3.67)* seek diet beverages Disclosure: JCP, JOH received consulting fees from Coca-Cola Company outside of the(10,13). submitted The remaining co-authors declared no conflict of in NNS—water (13.12) 22.22 (12.96) 21.90 21.16,work. 22.63 <0.0001 beverages on weight loss using an20.32 equivalence trial design. Author contributions: JP, HW, GF, ZP, JH, were involved in study design, data analysis and data interpretation; CB, SH, SV, AW were involved in data collection authors were involved in writing the manuscript and approved the final submission. The largest and 7most recent randomized trial27(14) to compare water, NNS were introduced into the food supply over 50 Received: years ago16and 2014; Accepted: March 2014; Published online May 2014. doi:10.1002/oby.20737 Analysis including participants who completed 12 weeks of theJanuary trial. Although equivalence cannot be established participants lost more weight in the NNS group as comdiet beverages and an attention control for their effects on weight are being used in hundreds of different food and beverage products. This is an open access article under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License, whichStatistically permits use and distribution in any pared to the water group. All analyses were completed using a Satterthwaite two sample t test. All values are Mean (SD) unless otherwise noted. significant the original work properly cited, the usetrial is non-commercial no modifications or adaptations loss isused a superiority design. The and authors found that the diet are made. Despite the long history of usage there continues to beprovided considerable values (P < 0.05) are shown by an asterisk (*) and statistically significant P values are shown in bold. controversy concerning their role in the diet, particularly whether beverage treatment, but not water, significantly increased the probawww.obesityjournal.org they are a useful tool as an aid in weight loss and weight loss main- bility of losing 5% of body weight over the 6-month study duration Obesity | VOLUME 22 | NUMBER 6 | JUNE 2014 REVIEW Does low-energy sweetener consumption affect energy intake and body weight? A systematic review, including metaanalyses, of the evidence from human and animal studies Low-energy sweeteners systematic review PJ Rogers et al PJ Rogers1, PS Hogenkamp2, C de Graaf3, S Higgs4, A Lluch5, AR Ness6, C Penfold6, R Perry6, P Putz7, MR Yeomans8 and DJ Mela9 By reducing energy density, low-energy sweeteners (LES) might be expected to reduce energy intake (EI) and body weight (BW). To Internation OPEN assess the totality of the evidence testing the null hypothesis that LES exposure (versus sugars or unsweetened alternatives) has no © 2016 Mac effect on EI or BW, we conducted a systematic review of relevant studies in animals and humans consuming LES with ad libitum www.natu access to food energy. In 62 of 90 animal studies exposure to LES did not affect or decreased BW. Of 28 reporting increased BW, 19 compared LES with glucose exposure using a specific ‘learning’ paradigm. Twelve prospective cohort studies in humans reported −2 inconsistent associations between LES use and body mass index (−0.002 kg m per year, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.009 to REVIEW 0.005). Meta-analysis of short-term randomized controlled trials (129 comparisons) showed reduced total EI for LES versus sugarsweetened food or beverage consumption before an ad libitum meal (−94 kcal, 95% CI −122 to −66), with no difference versus water (−2 kcal, 95% CI −30 to 26). This was consistent with EI results from sustained intervention randomized controlled trials (10 comparisons). Meta-analysis of sustained intervention randomized controlled trials (4 weeks to 40 months) showed that consumption of LES versus sugar led to relatively reduced BW (nine comparisons; −1.35 kg, 95% CI –2.28 to −0.42), and a similar relative reduction in BW versus water (three comparisons; −1.24 kg, 95% CI –2.22 to −0.26). Most animal studies did not mimic LES consumption by humans, and reverse causation may influence the results of prospective cohort studies. The preponderance of PJ Rogers1, PS Hogenkamp2, C de Graaf3, S Higgs4, A Lluch5, AR Ness6, C Pen evidence from all human randomized controlled trials indicates that LES do not increase EI or BW, whether compared with caloric or non-caloric (for example, water) control conditions. Overall, the balance of evidence indicates that use of LES in place of sugar, in By reducing energy density, low-energy sweeteners (LES) might be expected t children and adults, leads to reduced EI and BW, and possibly also when compared with water. Does low-energy sweetener consump and body weight? A systematic revie analyses, of the evidence from huma assess the totality of the evidence testing the null hypothesis that LES exposu effect on EI or BW, we conducted a systematic review of relevant studies in International Journal of Obesity (2016) 40, 381–394; doi:10.1038/ijo.2015.177 access to food energy. In 62 of 90 animal studies exposure to LES did not affe compared LES with glucose exposure using a specific ‘learning’ paradigm. Tw inconsistent associations between LES use and body mass index (−0.002 kg 0.005). Meta-analysis of short-term randomized controlled trials (129 compar sweetened food or beverage consumption before an ad libitum meal (−94 k INTRODUCTION Although thewater imprecise of toshort-term balance (−2 kcal, control 95% CI −30 26). This wasenergy consistent with EI results from su predicts that(10LES consumption should help reduce EI and Low-energy sweeteners (LES), such as acesulfame-K, aspartame, comparisons). Meta-analysis of sustained intervention randomized contro 3,10 therefore reduce risk of overweight it is reduced possibleBW (nine compar consumption of LES versus and sugarobesity, led to relatively saccharin, stevia and sucralose are consumed throughout the that, as consumed everyday life,versus otherwater effects of LES balance −1.24 or kg, 95% CI –2 relativein reduction in BW (three comparisons; world.1 The history of their use has been accompanied by debate consumption by humans, reverseFor causation may ainfluence even outweigh the energy dilutionandeffect. example, low the results o and disagreements, not least about their potential nutritional evidence human randomized controlled trials calorie or ‘diet’ labelfrom mayall cause the consumer to eat a indicates larger that LES do no impact. The use of LES to replace or partially replace added sugar non-caloric (for example, water) control conditions. Overall, portion of the product or eat more of accompanying foods in thethe balance of ev in foods and beverages might well be expected to reduce energy 2–4 and11–14 adults, leadssimply, to reduced EI and BW, and possibly meal, or eat children more later. More adding sweetness to a also when co intake (EI), yet over recent years there has been widely reported Efecto en el peso: edulcorantes v/s azúcar speculation that consumption of LES might increase the risk of 5–7 product may increase intake owing to increased palatability.15,16 International of Obesity between (2016) 40, 381–394; doi:10.1038/ijo.2015.177 Or, by ‘uncoupling’ theJournal relationship sweetness and Placer por lo dulce, azúcar y obesidad Edulcorantes artificiales: no tan rápido! Mecanismos propuestos para el “daño” Evidencia actual Conclusiones Conclusiones • Se ha establecido una relación de causalidad entre el consumo de azúcar y bebidas azucaradas con el aumento de la prevalencia de sobrepeso y obesidad a nivel mundial • Los edulcorantes artificiales no calóricos representan una alternativa de valor al disminuir el aporte de azúcar de alimentos y sobre todo bebidas • Estudios observacionales han reportado asociación entre el uso de edulcorantes no calóricos y riesgo de obesidad • No se ha encontrado causalidad para esta relación • De la gran cantidad de estudios, de diferente diseño, publicados, se puede desprender que el uso de edulcorantes no tendría efectos adversos en baja de peso ni su mantención. • No se ha demostrado beneficio significativo en la baja de peso con el uso de edulcorantes artificiales. • Por qué habría de esperarse que sólo por el hecho de consumir edulcorantes no calóricos alguien pudiera perder peso??... • Los edulcorantes no calóricos podrían promover la baja de peso en el contexto de una “dieta” o cambios activos en la conducta alimentaria.