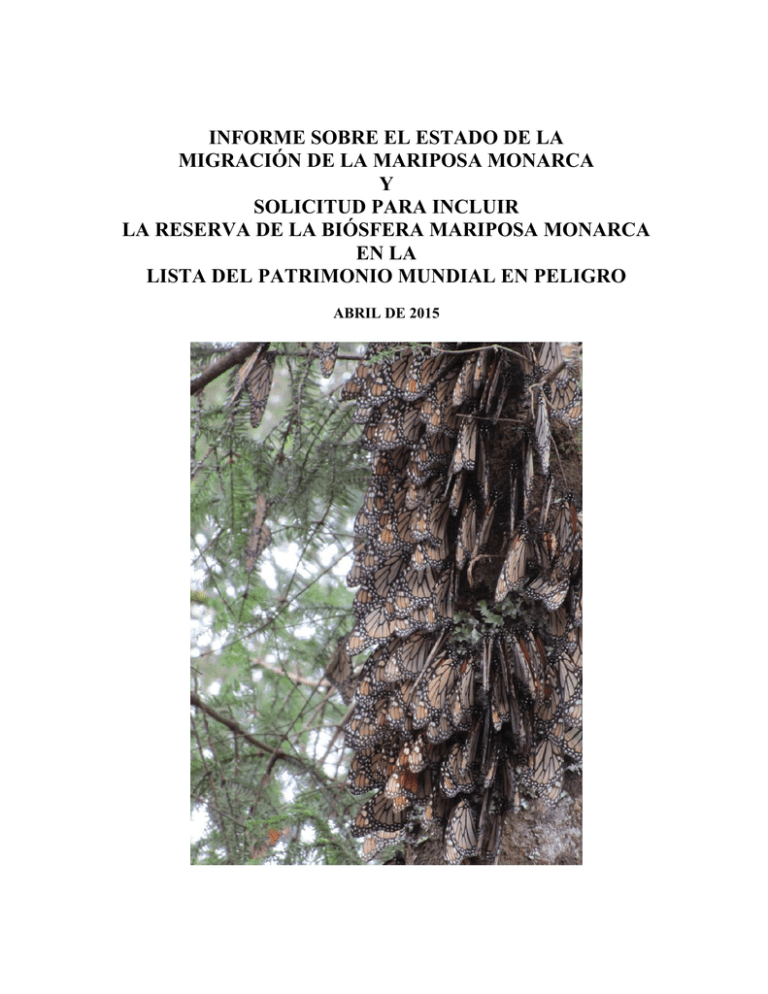

informe sobre el estado de la migración de la mariposa monarca y

Anuncio