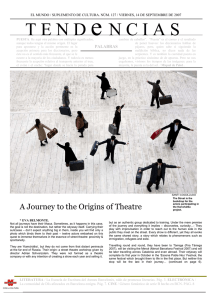

Eugenio Barba, Iben Nagel Rasmussen, The Blind Horse. Eugenio

Anuncio

Eugenio Barba, Iben Nagel Rasmussen, The Blind Horse. Eugenio Barba’s Performances (Book about to be published; the original Danish version has been published in 1998) ODIN TEATRET IN DENMARK During the time when I was travelling around Europe spreading information about Grotowski's work, whenever I met someone I would end the conversation saying: who do you think might be interested in this type of theatre? Usually I would get the names of some people who I then contacted on my continuous trek in search of allies. When I was travelling through Denmark in 1964, I visited the literary magazine “Vindrosen” to speak to the editor, Jess Ørnsbo, and also told him about Grotowski. As usual, I ended by asking: "Who do you think might be interested in this type of theatre?" He gave me the name of Christian Ludvigsen whom I visited the next evening. It is difficult to express what it meant to me when, shortly afterwards, I received a letter from Christian in Norway where, together with my four aspiring actors, I was trying to stick to my confused plans for the future. The relationship with Christian Ludvigsen has continued to this very day. He reviewed the first issue of “TTT - Teatrets Teori og Teknikk” (Theatre's Theory and Technique), which Odin Teatret began publishing in 1965, and he organised our first tour to Aarhus in collaboration with Jens Okking, the director of a small theatre called Vestergade 58. It was also through Christian that I came into contact with the university where Tage Hind was teaching. Tage suggested that I give a lecture to the students. I was thunderstruck. I had done many strange forms of work in my life. But giving a lecture on theatre at a university was something new. It made me nervous and very embarrassed, but I accepted because I imagined it would give Odin Teatret a certain amount of prestige. Christian Ludvigsen's brother-in-law had arranged a guest performance for us in Viborg. (Thus I discovered that even in Denmark family connections are a help). The brother-in-law's name was Peter Seeberg. It was there that a nurse from Holstebro turned up to see Ornitofilene. She had connections with a small amateur theatre in her town, had attended Tage Hind's classes in dramaturgy, and it was there she had heard about this strange theatre from Norway. She was so enthusiastic about the performance that the next day she phoned the head of the Town Council in Holstebro. She said to him that if they really believed in the town’s future as a centre of culture - a statue by Giacometti had already been purchased and they were in the process of appointing a composer of electronic music as the official town composer - why not then acquire a theatre that could also function as a theatre school? At that time there was a lively debate in Denmark on the reform of theatre schools. Inger Landsted's conversation with the head of the Town Council resulted in an invitation. She was welcome to come to the Town Hall immediately. He listened to the idea about a theatre and thought it sounded very interesting. Could a meeting be arranged with the director? It was as though God had sent a messenger with a miracle. In Oslo we had already been dreaming of moving out of the city and had tried in vain to find refuge in Frederikstad and Lillehammer. I thought that a small town in western Jutland sounded fantastic and left Aarhus for Holstebro along with our administrator, Agnete Strøm, and Tage Hind. I was hoping that having a university professor with me would make an impression on the local authorities. I had imagined western Jutland as moorland, a boundless expanse covered in heather, just as I had read about it in Oslo. But already the trip over there depressed me, and when we finally arrived the town turned out to be rather dismal. It looked more like a grey, bedraggled cockerel than a centre of culture. I realised that it would be an almost impossible task to do theatre in such a place. There were simply not enough spectators. The mayor and three or four members of the town council were present at the meeting. Halfway into the discussion over the conditions and terms of our possible move to Holstebro, I happened to mention that we neither wanted to start a theatre school nor an ordinary theatre, but a theatre laboratory. There was total silence; no one uttered a word until the mayor, Kaj K. Nielsen, asked straight out: "Exactly what is a theatre laboratory?" My immediate reply was: "A theatre that doesn't perform every evening". They found this quite acceptable. The municipality of Holstebro had bought a number of properties on the outskirts of town, one of which was a farm that was to be used by the Civil Defense. It was suggested that one wing be turned into a theatre. We received an annual cash grant of seventy-five thousand kroner. This was enough to pay each of us a wage that amounted to that of an unskilled worker. There are photographs from that time that I am very fond of. They were taken during a press conference at which we told the local newspaper about our grandiose projects and plans. We asserted that the town would doubtless become famous and be put on the world map because of our activities. One of the photos shows Odin Teatret’s actors and myself on the farm bought by the municipality and which was still in use as such. There we stand with wistful looks, as we gaze at the pigs in the stable that would later become the theatre where Jerzy Grotowski, Dario Fo, Luca Ronconi, Jean-Louis Barrault and many others would perform. In June 1966 we moved to Denmark. I didn't know how to tackle the situation in which we found ourselves in Holstebro. On the one hand, our little group - Torgeir, Else Marie, Anne Trine, myself and our secretary Agnete Strøm - was virtually an amateur one. On the other hand, we were suddenly the object of an unbelievable amount of attention - from the town council, from the town and from the press. I was interviewed and asked to state my views on everything between heaven and earth. My experiences while travelling around Europe spreading information about Grotowski turned out to be very useful, for although at the time I had visited people as a totally anonymous student, I needed nevertheless to come across with a certain aplomb. I had learnt to adopt a courteous and informed attitude. The move to Holstebro soon changed my function within the group. In Oslo we could concentrate on training and on the performance, working from nine to five. When we came to Holstebro we started at seven in the morning. I thought quite simply: theatre is a craft, and if craftsmen start their day at seven o’clock, as I did when I was a welder in Oslo, then we will do the same. How could Odin Teatret consolidate its presence in Holstebro, I asked myself. Not merely win over an audience. Our performances were conceived for a limited number of spectators, about sixty at that time, and they were very different from what was usually seen. Precisely for that reason, I believed that we had to make ourselves known through other activities and become an important part of the town and the social context. Our first activity was a large seminar with Grotowski and Ryszard Cieslak, as well as Stanislaw Brzozowski from Henrik Tomaszewski’s Pantomime Theatre in Poland. The seminars came about out of a need on the part of both the actors and myself. We very much wanted to encounter certain theatre personalities, see them in action and witness their working methods. Later, people such as Etienne Decroux, Jacques Lecoq, Jolanda Rodio and Dario Fo also took part. At the first two seminars, which were held in the summer, the actors and I all taught, especially Torgeir, though he was still very young - only nineteen or twenty. We also assumed all practical responsibilities, secured funds, washed the dishes, went shopping, duplicated documents, put up beds, etc. Later on we held seminars in the spring as well. The first one was on Czechoslovakian theatre. All these activities meant that there were periods in which we were very outgoing. At the same time, it was a way of establishing contacts within the town. Among the participants there were a number of well-known Scandinavian actors, a fact which vouched for the quality of what we were doing. What is more, many people were housed in private homes around Holstebro during the month the seminar lasted. And last but not least, organising seminars was a way for Odin Teatret to earn money. The need to be a presence in Holstebro has evolved through the years and has found its expression in the festivals, seminars and guest performances we have regularly organised. I have always felt enormous gratitude towards Holstebro and to the town council which at the time had the courage to invest in a totally unknown Norwegian group. Occasionally people ask me if I didn't often have doubts during those first years when I was not yet known and had not reached the artistic and professional level that I have achieved today. But I had no doubts; I knew what I wanted. I was resolute, yet without really knowing why I was so certain. If, during work on a performance, I had a definite idea of what I wanted but it didn’t work, then the only thing to do was to look for a new solution that did. It is only when you have a concrete proposal that you can decide, adjust, make changes and find out what course to follow.