Heading South: The dash for unconventional fossil fuels in

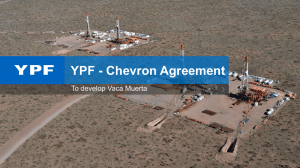

Anuncio