Descargar publicación

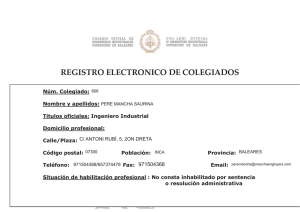

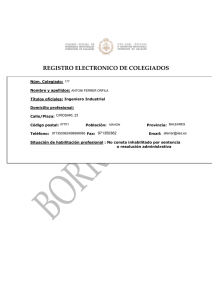

Anuncio