Debt/GDP - Compass Group

Anuncio

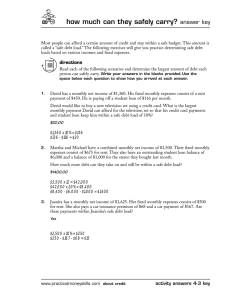

Fundamentos macro y riesgo soberano: ¿qué hemos aprendido? March 2013 Roger Aliaga-Diaz, PhD Senior Economist Vanguard Investment Strategy Group For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. Developed markets government debt: Reaching record highs … during peace time Public debt in advanced economies, 1880–2012 130 120 110 100 % of GDP (weighted avg) 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 1880 1900 1920 1940 1960 1980 2000 Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, October 2012. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 2 Which countries are above average? Government debt-to-GDP ratios for selected economies in 2012 250 237 200 % of GDP 171 150 126 100 83 90 119 118 107 91 89 94 UK Iceland 50 0 Japan Germany France Spain Greece Italy Portugal Ireland US Four numbers for U.S. government debt Gross Net General 107.2 83.8 Central 103.2 72.5 Sources: US Bureau of Public Debt, U.S. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis , International Monetary Fund (IMF): World Economic Outlook ©2012 For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 3 Assessing government debt overhangs General questions • What is wrong with the current paradigm for evaluating sovereign debt risk? • What are the ways out of debt? What works and what doesn’t? Specific questions • Is debt-to-GDP a good indicator of debt sustainability? • Does harsh austerity pay off? • Should central banks stay out of the problem? For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 4 Macro fundamentals and sovereign debt math: Debt limits, fiscal space and the primary balance Accounting formula Interest service (r x debt) – Primary balance = Growth in outstanding debt For Debt/GDP ratios: (r – g) x Debt/GDP ratio – Primary balance/GDP = Debt/GDP ratio growth (r-g)d Current paradigm 1. Higher the Debt/GDP ratio requires higher government savings 2. “Debt limit” is the max Debt/GDP ratio beyond which markets loose credibility on the government’s fiscal adjustment plans 3. “Fiscal space” indicates how close the debt/GDP ratio is to the “debt limit” Primary Balance Int. rate schedule with endogenous risk premium and default probability, p (r(p)-g)d (r(0)-g)d Primary Balance Risk free int. rate, r(0)-output growth rate g Debt limit Debt/GDP Sources: “Fiscal Space”, by Jonathan D. Ostry et al, IMF Position Notes, September 2010. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 5 Fiscal space framework: Too much focus on debt/GDP and deficits/GDP Moody’s estimates of Fiscal Space, 2012 For Debt/GDP ratios: 250 South Korea (r – g) x Debt/GDP ratio 229 Norway 223 Australia – Primary balance/GDP 203 Sweden 197 Switzerland = Debt/GDP ratio growth 182 Finland 174 United States 162 Canada 158 Germany 1. Is (r-g) > or < 0 or ~0 154 Austria 137 United Kingdom 2. What determines “r”? What determines risk premia embedded in “r”? 129 France Belgium 118 Ireland Grave Risk (0-40) 93 Greece 0 3. What can be done about “g”? Significant Risk (41-69) Italy 0 4. How does “g” impacts the primary balance? Caution (70-124) Japan 0 Spain 0 Safe (>124) Cyprus 0 Portugal 0 0 50 100 150 200 250 300 Sources: Moody’s economy.com, Update as of December 2012. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 6 Fiscal space framework: “Panic” austerity has real effects Fiscal multipliers during 2010–11 8 Austerity and changes in debt-GDP ratio 50 y = -1.16x + 0.67 R² = 0.51 45 Increase Debt ratio (% of GDP) GDP growth impact 2011 (ppts) 6 4 Multiplier ~ 1.2 2 0 -2 -4 -6 40 35 Greece 30 Portugal 25 Ireland 20 15 Spain 10 Italy 5 0 Germany -5 -8 -4 -2 0 2 4 Unexpected fiscal consolidation 2010–2011 (% of potential GDP) 6 0 5 10 15 Austerity Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook, October 2013 and “Panic-driven austerity in the Eurozone and its implications”, Paul De Grauwe and Yuemei Ji, February 2013. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 7 High debt-to-GDP ratio for developed markets: We have been here before … multiple times Debt-to-GDP dynamics after public debt reaches 100 percent of GDP 300 ISR 1977 FRA 1916 250 GRC 1888 GBR 1918 JPN 1997 NLD 1932 200 150 NZL 1884 ITA BEL 1921 NZL 1909 CAN 1932 ITA 1992 BEL 1983 100 GRC 1993 FRA 1884 NLD 1887 ESP ITA 1919 GRC 1931 50 USA 1946 IRL 1986 BEL 1940 CAN 1995 ITA 1942 GER 1918 0 1875 1890 1905 JPN 1942 1920 1935 1950 1965 1980 1995 2010 Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF): World Economic Outlook, October 2012. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 8 Learning from history: what is next after reaching 100% debt/GDP? Debt-to-GDP dynamics after crossing the 100% threshold (% of GDP of advanced economies) 240 10th/90th percentile 25th/75th percentile 220 Japan 1997 UK 1918 200 Median 180 160 140 120 Italy 1992 100 80 USA 1946 60 40 20 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF): World Economic Outlook, October 2012. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 9 Learning from history 1. UK in the 20s and 30s - the orthodox way United Kingdom’s debt-to-GDP dynamics after crossing the 100% threshold (% of GDP of advanced economies) 240 10th/90th percentile 25th/75th percentile Median 220 200 15 Decomposition of annual change in debt 10 180 160 5 140 120 100 0 80 60 -5 40 20 -10 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Nominal interest rate GDP growth Residual Inflation Primary balance Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF): World Economic Outlook, October 2012. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 10 Learning from history 2. US in the 50s and 60s- financial repression and surprise inflation United States’ debt-to-GDP dynamics after crossing the 100% threshold (% of GDP of advanced economies) 240 10th/90th percentile 25th/75th percentile Median 220 200 4 Decomposition of annual change in debt 2 180 160 0 140 -2 120 100 -4 80 60 -6 40 20 -8 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Nominal interest rate Inflation GDP growth Primary balance Residual Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF): World Economic Outlook, October 2012. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 11 Learning from history 3. Japan in the 90s - Deflation Japan’s debt-to-GDP dynamics after crossing the 100% threshold (% of GDP of advanced economies) 240 240 10th/90th percentile 25th/75th percentile Median 220 200 220 200 180 180 160 160 140 140 120 120 100 100 80 80 60 60 40 40 20 20 0 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 12 Decomposition of annual change in debt 10 8 6 4 2 0 -2 Nominal interest rate Inflation GDP growth Primary balance Residual Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF): World Economic Outlook, October 2012. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 12 Learning from history: Summary 1. Supportive monetary environment is necessary condition for fiscal adjustment 2. Commitment to an external currency anchor (i.e. gold standard) worsen the outcomes 3. Fiscal adjustment requires the economy to be strong 4. Deflation and low growth worsen the debt dynamics 5. Financial repression with inflation surprises worked in the past, but it may not be possible today For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 13 ECB balance sheet is the only effective tool against short-term break-up risk Yields of Eurozone sovereign bonds Market weighted average yield LTROs €1 trn 8% OMT Unlimited 7% SMP €200 bn Yield to maturity 6% 5% 4% 3% 2% 1% 0% 2008 2009 Germany France 2010 Spain 2011 2012 Italy Notes: Reflects the yield to maturity for each country’s index within the Barclays Capital Euro Aggregate Treasury All Market Index. Data through 15 October 2012. Source: Barclays Capital. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 14 Central banks’ lender-of-last-resort role may be more important than debt-to-GDP ratios Debt-to-GDP and interest rates, 2013 Change in spreads vs initial spreads for selected countries (June 2012–January 2013) 25 2 0 Euro 20 Change in spread (%) 15 10 5 France Ireland -2 Non-Euro Interest rates UK Portugal -4 -6 Italy Spain -8 -10 -12 -14 -16 0 Greece -18 0 50 100 150 Gross ebt-to-GDP 200 250 0 10 20 Initial spread (%) 30 Source: International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database, Thomson Reuters Datastream and “Panic-driven austerity in the Eurozone and its implications”, Paul De Grauwe and Yuemei Ji, February 2013. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 15 Central banks’ quantitative easing policies: Are they already acting as lenders of last resort? Central bank total assets 30 ECB Lehman Brothers collapse Total assets (% of 2008 GDP) Fed 25 BoE BoJ 20 15 10 5 0 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 Source: Vanguard Investment Strategy Group calculations based on IMF, Federal Reserve and Bank of England and Bank of Japan. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 16 “Fiscal dominance” and inflation are the key risks Central banks stance and real policy rates 10% ZLB policy 8% Interest rate rule 6% 4% 2% 0% -2% -4% US UK Core inflation Eurozone Canada Japan Mexico Australia Brazil China India Real policy rate Notes: Core inflation measured as the year/year change in that countries CPI ex food and energy index, except for India which displays the headline inflation number. Real policy rate is defined as the country's primary monetary policy target interest rate, adjusted by core inflation . Data as of 10 July 2012. Sources: Various international statistical agencies, compiled from Thomson Reuters and Moody's Analytics. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 17 What have we learned? 1) Too much focus on debt-to-GDP and “panic” fiscal adjustments. The macro accounting arithmetic should also include GDP growth rates, their impact on fiscal balances and the determinants of interest rates. (Japan vs Greece) 2) The monetary regime is a critical component of sovereign debt risk assesments. For currency unions, currency boards, gold standard or fixed-exchange rates settings, “breakup” risk amounts to default risk. (Spain vs UK) 3) Fiscal and monetary policy coordination is necessary. Credible fiscal consolidation plans must be accompanied by ample monetary support. Avoiding a deflationary trap is critical. QE policies seem to be appropriate here. (No country is doing this right now). For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 18 Appendix For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 19 A look back at post-WWII debt reduction: Mostly growth, but also inflation and belt-tightening Cumulative contribution to post-WWII reduction of U.S. gross debt/GDP 250.0 Financial Repression Belt tightening 200.0 Inflation 8% Real GDP growth Debt/GDP 150.0 22% 9% 21% 20% 30% 100.0 50% 40% 50.0 For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 1970 1969 1968 1967 1966 1965 1964 1963 1962 1961 1960 1959 1958 1957 1956 1955 1954 1953 1952 1951 1950 1949 1948 1947 1946 0.0 20 A look back at post-WWII debt reduction Would inflating our way out work? Composition of U.S. federal spending 100% 80% Defense 60% Other Non Interest Net Int Medicare 40% Social Security 20% 0% 1946 2010 110% Net Debt/GDP 65% Net Debt/GDP For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 21 Learning from history: what is next after 100% debt/GDP? Italy’s Debt to GDP Dynamics after Crossing the 100% Threshold (% of GDP of advanced economies) 240 Decomposition of debt 10th/90th percentile 25th/75th percentile Median 220 200 10 8 180 6 160 4 140 2 120 0 100 -2 80 -4 60 40 -6 20 -8 0 -10 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Nominal interest rate Inflation GDP growth Primary balance Residual Source: International Monetary Fund (IMF): World Economic Outlook ©2012. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 22 Disclosures This information is intended for investors outside the United States. The information contained herein does not constitute an offer or solicitation and may not be treated as an offer or solicitation in any jurisdiction where such an offer or solicitation is against the law, or to anyone to whom it is unlawful to make such an offer or solicitation, or if the person making the offer or solicitation is not qualified to do so. All investing is subject to risk, including the possible loss of the money you invest. Investments in stocks or bonds issued by non-U.S. companies are subject to risks including country/regional risk and currency risk. Bond funds are subject to the risk that an issuer will fail to make payments on time, and that bond prices will decline because of rising interest rates or negative perceptions of an issuer's ability to make payments. © 2013 The Vanguard Group, Inc. All rights reserved. For institutional use only. Not for public distribution. 23