¿Colocolo o lo coloco?: The position of the clitic pronoun in old

Anuncio

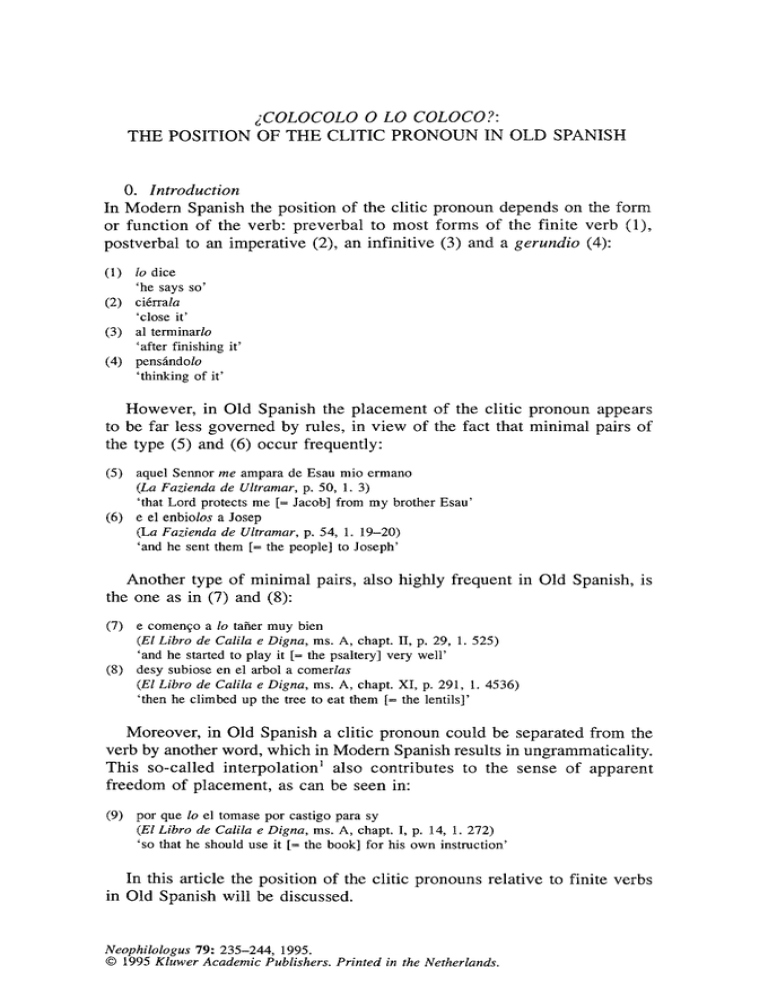

gCOLOCOLO 0 LO COLOCO?: THE POSITION OF THE CLITIC PRONOUN IN OLD SPANISH O. Introduction In M o d e r n S p a n i s h the p o s i t i o n o f the clitic p r o n o u n d e p e n d s on the f o r m o r f u n c t i o n o f the v e r b : p r e v e r b a l to m o s t f o r m s o f the f i n i t e v e r b (1), p o s t v e r b a l to an i m p e r a t i v e (2), an i n f i n i t i v e (3) and a gerundio (4): (1) lo dice 'he says so' (2) ci6rrala 'close it' (3) al terminarlo 'after finishing it' (4) pens~indolo 'thinking of it' H o w e v e r , in O l d S p a n i s h the p l a c e m e n t o f the clitic p r o n o u n a p p e a r s to be far less g o v e r n e d b y rules, in v i e w o f the fact that m i n i m a l pairs o f the type (5) and (6) o c c u r frequently: (5) aquel Sennor me ampara de Esau mio ermano (La Fazienda de Ultramar, p. 50, 1. 3) 'that Lord protects me [= Jacob] from my brother Esau' (6) e el enbiolos a Josep (La Fazienda de Ultramar, p. 54, 1. 19-20) 'and he sent them [= the people] to Joseph' A n o t h e r t y p e o f m i n i m a l pairs, also h i g h l y f r e q u e n t in O l d Spanish, is the one as in (7) and (8): (7) e comen~o a lo tafier muy bien (El Libro de Calila e Digna, ms. A, chapt. II, p. 29, 1. 525) 'and he started to play it [= the psaltery] very well' (8) desy subiose en el arbol a comerlas (El Libro de Calila e Digna, ms. A, chapt. XI, p. 291, 1. 4536) 'then he climbed up the tree to eat them [= the lentils]' M o r e o v e r , in O l d S p a n i s h a clitic p r o n o u n c o u l d b e s e p a r a t e d f r o m the v e r b by another word, w h i c h in M o d e r n S p a n i s h results in u n g r a m m a t i c a l i t y . T h i s s o - c a l l e d i n t e r p o l a t i o n I also c o n t r i b u t e s to the s e n s e o f a p p a r e n t f r e e d o m o f p l a c e m e n t , as can be seen in: (9) por que lo el tomase por castigo para sy (El Libro de Calila e Digna, ms. A, chapt. I, p. 14, 1. 272) 'so that he should use it [= the book] for his own instruction' In this article the p o s i t i o n o f the clitic p r o n o u n s r e l a t i v e to finite v e r b s in O l d S p a n i s h will be discussed. Neophilologus 79: 235-244, 1995. © 1995 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. Dorien Nieuwenhuijsen 236 1. Previous studies Generally, studies about the position of the clitic pronoun in Old Spanish have sought a set of rules on which the placement of the clitic depended, focusing on the element previous to the verb. This element should determine the position of the clitic, i.e., preposed or postposed to the verb. The first study to treat the position of the clitic pronoun in detail is the one by Gessner (1893). Here he identifies a number of contexts, indicating for each one if it favours preposition or postposition of the pronoun. Table 1 summarizes his findings as well as those of Ramsden (1963) and Barry (1987), which will be discussed below. 2 The principle underlying Gessner's set of rules is that in Old Spanish clitic pronouns always needed some other element to cling to in postposition. This could explain the fact that clitics do not occur in sentence-initial position (cf. Table 1, category a) and that in negative sentences they are always preverbal (cf. Table 1, category c), for in negative sentences the demand for another element is always met, owing to the presence of the negation. 3 Table 1 Gessner Ramsden Barry (1893) (1963) (1987) pre pos pre (x) x (x) x pos pre pos - - a) [¢)]_ b) e 'and' c) [negation]_ x x x d) [interrogative/exclamative pronoun/adverb] __ - - x x e) [subordinate clause], __ (clitic in main clause) (x) x x x - - f) ca (x) x x x - - g) [subject]_ x x x x - - [object] (4 referent of clitic) __ x x x [adverb] __ x x x [prepositional/adverbial phrase] __ x x x 'because' x - (x) - - x - - x - - - - x (x) [object] (= referent o f clitic) _ _ i) [infinitive/gerundio/past j) in subordinate clause x (x) x - k) finite verb = imperative x x - - x x [O] = v e r b i n s e n t e n c e - i n i t i a l p o s i t i o n ; e _ _ = v e r b a f t e r e, etc. pre = clitic in preverbal position p o s = clitic in p o s t v e r b a l p o s i t i o n x = p o s i t i o n o f t h e c l i t i c as r e p o r t e d b y t h e a u t h o r (x) = n o t f r e q u e n t p o s i t i o n - = no data available x - h) participle] __ x x x The Clitic Pronoun in Old Spanish 237 Although Gessner's study is considered the first thorough introduction to the problem, one cannot but conclude, in view of the number of rules and their exceptions, that the system of placement of the clitic pronoun in Old Spanish was highly complicated and that in Modern Spanish the rules for placement have been simplified to a great extent. On the whole, Ramsden (1963) arrives at the same conclusions as Gessner as far as the influence of the element preceding the verb is concerned (see Table 1). However, his starting-point seems to be fundamentally different. Whereas Gessner examines each context for the presence of an element that suits the clitic pronoun to cling to, Ramsden sustains that the logical and functional union between the preceding element and the verb is responsible for the position of the clitic: the stronger the union between the two elements, the greater the tendency to place the clitic before the verb. Thus, Ramsden considers the placement of the clitic pronoun subject to a functional principle which holds for each and every context. Yet, Ramsden's hypothesis raises the following two questions: i) why does a strong union between a verb and its preceding element lead to a preverbal clitic placement and a lack of such union to a postverbal placement? ii) why do some elements join closely with the following verb while others, also preposed, are only loosely connected with it? Ramsden's study does not take either of the questions into consideration. As far as the first one is concerned, it remains to be seen whether a close union between verb and preceding element should allow interruption of a pronoun, thus separating the two. Here, Ramsden seems to be implying that in case of a close union between verb and preceding element the latter is an appropriate candidate for the clitic pronoun to lean on. But, if we are to suppose that this argument underlies Ramsden's hypothesis, we are then forced to conclude that there is no difference whatsoever between his hypothesis and Gessner's guiding principle. On the other hand the degree of union between verb and preceding element, as questioned in ii), has to be deduced, so it seems, from the fact that preposition of postposition of the clitic is favoured in a given context. But in that case we cannot avoid the impression of circularity: a close union leads to prepositioning while preposition implies a close union. In a short article, Barry (1987) views the problem from a totally different angle. She observes that in thirteenth-century Spanish prose texts clitic pronouns show (almost) uniform behaviour when the verb is placed at the beginning of the sentence, in subordinate clauses, with affirmative commands, in questions and in negative sentences (see Table 1), whereas variation in placement only occurs in affirmative, declarative main sentences. She claims that of the latter type of sentences only a subset is used to tell the story and to provide us with new and important information, whereas the rest of the affirmative declarative main sentences, subordinate clauses, negative sentences, questions and commands all present 238 Dorien Nieuwenhuijsen background information. Given this fundamental difference in discourse function between a subset of affirmative declarative main sentences on the one hand and another subset of affirmative declarative main sentences, subordinate clauses, negative sentences, questions and commands on the other hand, Barry claims that: "a clitic pronoun precedes a finite verb unless the clause which contains it has a foregrounding function, in which case the clitic is postverbal" (1987: 215). This should mean that in thirteenthcentury Spanish the position of the clitic pronoun was used as a syntactic device to label the type of information given. The principle would explain the fluctuation of placement in main sentences as well as the uniform placement in the other types of sentences, as mentioned above. Barry's proposal is interesting because it claims that in Old Spanish clitic pronoun placement was guided by a functional, syntactic principle. However, it also gives rise to some doubts. Firstly, Barry argues that negatives sentences, in which the pronoun is always preverbal, never have a foreground function, i.e., are never part of the story line. Yet, it is hard to believe that negative sentences will never be employed to tell a main event. Secondly, the fact that clitic pronouns do not occur in sentence-initial position plays a vital part in Barry's argument. It serves to explain examples in which a verb stands at the beginning of the sentence and provides background information (like imperatives, according to Barry). On the basis of the discourse function of the verb, in such cases one would expect the clitic to be preposed, btu nevertheless the examples invariably show postposition, this being due to a so-called phonological restriction, i.e., that the clitic pronoun cannot stand in sentence-initial position. In Barry's view this restriction is a very powerful one, for, whenever it comes into conflict with the functional principle of discourse function, it eliminates the operating of the last. 2. A new proposal As a starting point for examining the position of the clitic pronoun relative to the finite verb it might be useful to focus our attention on the general word order in Old Spanish. For Late Latin Ramsden (1963: 114) states the order S-V-O, an order which, as far as V and O are concerned, is confirmed by Lapesa (1981: 217) for Old Spanish. In addition, England (1980, 1983) has investigated the position of direct and indirect object NPs relative to the verb in Spanish texts covering the period 1250-1450. He concludes that the order V-O predominates in Old Spanish, both in case of a direct object NP and in case of an indirect object NP (1980: 3; 1983: 385); the O-V order is held to be marked (1980: 6). Bolinger claims that an element "which is presupposed but needs to be stated in order to clarify or remind, precedes" (1954: 48). So, given the standard word order of V-O, an object is placed before the verb if, on the one hand, it is presupposed, but on the other hand it is not sufficiently The Clitic Pronoun in Old Spanish 239 clear that this specific object is involved, for example because it has been only implicitly present in the previous context. England shows that the principle as stated by Bolinger also holds true for Old Spanish. His analysis suggests the existence of two types of objects which, deviating from the normal order of V-O, are frequently preposed (1980: 7; 1983: 383-384): thematic objects and emphatic or affective objects. Basing himself on the concepts of theme and rheme of the Prague school and, more specifically, on Contreras's definition (1976: 16) of the two, England states that thematic objects are the ones that are assumed to be present in the hearer's consciousness, and, as in the normal order of theme-rheme (Contreras 1976: 15), they are likely to preceed the verb. On the other hand, emphatic objects are those which transmit new and important information. Contreras (1976: 89) calls this type of examples, where, contrary to the normal order, the rheme preceeds the theme, emphatic sentences. Now, whereas the nature of the two types of objects is fundamentally different, they have in common that they both draw attention to themselves, i.e., to the entity to which they refer; the thematic objects do so because, being absent, they are at risk of being neglected or forgotten by the hearer, the emphatic because they convey a new, important notion. In summary, it seems legitimate to conclude that if in Old Spanish the normal word order is broken by placing an object before the verb, the former calls for the special attention of the hearer towards itself. Now let us suppose that the principle governing the position of NP objects in Old Spanish applies to all Old Spanish objects, i.e., not only to the full objects but also to the ones referred to by a clitic pronoun. In that case, when a clitic pronoun appears in preverbal position, there also is a deviation of the normal word order of V-O 4 and consequently the purpose of this deviation should be to draw attention. However, while in the case of an NP object preposition is used to draw attention to the entity to which the NP refers, preposition of a clitic pronoun cannot be meant to have the same objective. For if a speaker actually wanted to emphasize (the presence of) the entity expressed by the clitic pronoun, instead of applying an atonic, clitic pronoun, the language provided him with a far more effective instrument, i.e., the use of the corresponding tonic pronoun preceded by the preposition a. 5 The following example (10) shows the emphatic value of the tonic pronoun. In this fragment the priest Almerich expresses his thanks to don Raimundo, the archbishop of Toledo, who has commissioned him to write down the history of ancient Israel, the so-called Fazienda de Ultramar, indeed a very important task. (10) el to clerigo Almerich, ar~idiano de Antiochya, rende gracias a Dios e a ty, por que a ti plaz que tan alta poridat e fazienda me enbias a demandar. (La Fazienda de Ultramar, p. 43, 1. 13) 'the priest Almerich, archdeacon of Antioch, thanks God and you, because it pleases you to send me a request for such an important and confidential matter.' 240 Dorien Nieuwenhuijsen Since there is another means available to focus on a certain entity and the atonic pronoun is inherently unfit to do so, it seems reasonable to suppose that the special attention called for by preposing the pronoun is needed for some other purpose. Now why could a speaker at a certain moment find it necessary to draw the hearer's special attention, in other words, to put the hearer on the alert? The speaker's one and only goal is to get his message across and logically he will do anything to achieve this. However, if the message he wants to get across is rather complex, i.e., the information he is giving is relatively difficult to process, 6 he runs a great risk the hearer will not get his message right and thereby his communicative goal is not achieved. In such cases the speaker will try to make the hearer aware of the fact that the given information and its processing is not that easy or obvious. Thus, the speaker uses the prepositioning of the clitic pronoun to call for the bearer's special attention, needed to interpret the message correctly. This would mean, then, that the motivation for clitic placement is essentially of a communicative nature and therefore, as Diver (1975: 2-3) claims, human behaviour once more turns out to be the determining factor in the structure of language in the sense that the design and structure of the language are directly motivated by the act of communication. At this point we might ask why the elitie p r o n o u n should come to be a mark of drawing attention. In any case, an element with such an important function should necessarily be a sentence basic element, since the syntactic principle proposed here will only be effective if it can be put to work at any moment, i.e., if the attention-marker is actually available whenever the speaker wishes to bring it into action. It is commonly agreed that the sentence basic elements are subject, verb and object (cf. Greenberg 1966: 76-77). At first sight there is no logical motive why the o b j e c t should come to be preposed in order to prepare the hearer for a particularly difficult task, given the fact that there is a much more prominent element, namely the subject. Then what made speakers choose the object for this special function, thus neglecting the subject? An explanation begins to emerge when we look at the nature of Spanish subjects and consider the fact that, both in Old and Modern Spanish, they do not always need to be explicitly present. Once the subject is introduced or at least the entity to which the subject refers is assumed to be present in the hearer's consciousness, with the following verb the ending suffices to indicate what subject is involved, i.e., showing that the subject has not changed. The following example (11) serves to demonstrate this: 7 (11) Sefior, ~ dizen que en tierra de Gurguen avia un rrico mercador, e O avia tres fijos, e despues que ~ fueron de hedad, ~ metieronse a gastar el aver de su padre (El Libro de Calila e Digna, ms. A, chapt. III, p. 42, 1. 659) '- Lord, [they] say that in the land of Gurguen there was a rich merchant, and [he] had three sons, and when [they] came of age, [they] started to spend their fathers fortune' - The Clitic Pronoun in Old Spanish 241 I checked the presence of the subject in my own corpus of clitic pronoun examples for six Spanish prose texts, dating from the thirteenth to the sixteenth century. Of these clitic examples only 40% or less has an explicit subject in the same sentence. 8 So, prepositioning of the subject to draw the hearer's special attention can only be used on a limited scale, i.e., in 40% of the cases or less, in which, on the contrary, the clitic pronoun is always at hand. Therefore, the subject does not seem to be an appropriate candidate to perform the communicative function as postulated for the clitic object. 3. The principle at work In order to catch a glimpse of the proposed principle at work we will examine two different types of sentences. As Table 1 shows, there are two contexts for which all three authors report uniform behaviour, i.e., negative sentences and sentences with the verb in initial position. Significantly, it was for these two Barry's hypothesis could not give a satisfactory explanation for the clitic placement, as was argued above. i. Negative sentences. Whereas Gessner explained the unexceptionally preverbal clitics in this syntactical environment as due to the very presence of the negation, since in this type of sentences there always is an element the pronoun can lean on, Barry argued that negative sentences always have a background function, hence the clitic stands before the verb. However, the following e x a m p l e (12) appears to be in contradiction with Barry's argument: (12) Oyolo Ruben e pesol e quisol enparar. "No lo matemos", dyxo, "ca nuestro ermano es, ny non vertamos nuestra sangre. Echalle en aquel poqo". (La Fazienda de Ultrarnar, p. 51, 1. 11) 'Reuben heard this and it distressed him and he wanted to help him [= his brother Joseph]. "Let us not kill him, for he is our brother, and let us not spill our blood. Throw him into that pit".' Because of Reuben's begging not to kill him, Joseph's life is saved, which later on turns out to be of vital importance for his brothers, since Joseph, having made his career in Egypt, is able to provide them with corn during a famine, thus saving their lifes in return. Therefore R e u b e n ' s request plays an essential part in the story and can hardly be considered as background information. Thus, B a r r y ' s motivation for the prepositioning of the clitic is invalidated as well. As far as the hearer is concerned the information given in a negative sentence is more difficult to process than that of an affirmative sentence. After all, in the former sentence the speaker expresses that an action or event is n o t taking place or has n o t occurred with regard to the entity represented by the pronoun. As the information rises to a more abstract, less controllable level (one cannot check if something does not exist or takes 242 Dorien Nieuwenhuijsen place), the hearer consequently has to make a greater mental effort to interpret it correctly. Therefore, in case of a negative sentence, the speaker will constantly feel the need to make the hearer aware of the mental problem the latter is to face, and he will place the clitic before the verb. ii. Sentences with the verb in initial position. For Gessner the total absence of clitic pronouns in sentence-initial position was a strong indication for the need of the pronoun to cling to some preceding element. On the other hand, this type of sentence caused Barry serious trouble, since the only way of explaining away the postposition of the clitic when the sentenceinitial verb had a background function was by claiming the overruling of the discourse principle by a phonological restriction. To make her point, Barry gives some examples of backgrounding clauses in her article. Among others, she mentions clauses "which provide a larger context for the main events of the story, or provide some relevant additional information" (1987: 216). The following e x a m p l e (13) would fit her definition of a backgrounding clause: (13) Fue Josep de genta fechura; e antos d61 la mugier de Furtifar e dixo: "Jaz comygo". E non quiso Josep. Dixo: "Mio sennor todo 1o que a, metido [a] en myo poder e non le far6 atal enganno". Dixogelo .i. dia e otro. (La Fazienda de UItramar, p. 52, 1. 28) 'Joseph had good looks; and Potiphar's wife came to like him and said: "Lie down with me". And Joseph did not want to. He said: "My master has trusted me with everything he has got and I will not deceive him that way". He told her so time after time.' The clause: dixogelo .i. dia e otro, with the clitics postponed, gives relevant additional information, since it reflects Joseph's firmness and loyalty to his master. However, it cannot be considered marking an essential stage in the story line, as this attitude cannot prevent Joseph from falling into disgrace with his master Potiphar, who puts him in prison, because of his wife's false accusations. For the hearer the processing of the information given in (13) and, more in general, in affirmative, declarative main sentences with the verb in sentence-initial position does not present any problem. He can understand the action or event expressed by the verb as bearing directly on the pronoun (cf. negative sentences) and the relationship between the information given here and in the preceding sentence is a relationship of 1 + 1 (cf. the relationship between a main and a subordinate clauseg). Therefore, in this type of sentence the speaker places the clitic pronoun after the verb, because there is no reason for breaking the normal word order, i.e., for drawing the special attention of the hearer. In our view postposition of the clitic onto a verb in first position is not due to a phonological restriction, but merely reflects the Old Spanish standard word order. 1° The Clitic Pronoun in Old Spanish 243 4. Conclusion I n this a r t i c l e I h a v e t r i e d to d e m o n s t r a t e that in O l d S p a n i s h t h e p l a c e m e n t o f the clitic p r o n o u n r e l a t i v e to the v e r b is u s e d b y the s p e a k e r as a f u n c t i o n a l , s y n t a c t i c d e v i c e to w a r n the h e a r e r that t h i n g s are n o t as e a s y as t h e y m a y s e e m to be. S o , c l i t i c p l a c e m e n t in O l d S p a n i s h s h o w s t h a t the h u m a n f a c t o r a g a i n s e e m s to p l a y a d e c i s i v e r o l e in t h e s t r u c t u r e o f l a n g u a g e ( D i v e r 1975: 3). T h e q u e s t i o n : do I have to p l a c e the clitic after o r before the verb?, as p a r a p h r a s e d in the title o f this article, in o l d t i m e s w o u l d n o t d r i v e a s p e a k e r crazy, u n l i k e the w o r d s Io co-loco ' c r a z y - c r a z y ' c o u l d s u g g e s t . A f t e r all, it w a s u p to the s p e a k e r to u s e t h a t f u n c t i o n a l d e v i c e in o r d e r to s e c u r e his o w n c o m m u n i c a t i v e i n t e r e s t s , i.e., to g e t his m e s s a g e across. Vakgroep R o m a a n s e Talen en Culturen Universiteit Utrecht K r o m m e N i e u w e g r a c h t 29 3512 H D Utrecht The N e t h e r l a n d s DORIEN NIEUWENHUIJSEN Notes 1. For more details about this phenomenon see fn 3. 2. Table 1 only contains the categories taken in consideration by at least two of the studies discussed in this section. 3. However, the principle does not account for Old Spanish examples which show interpolation of some element between the verb and the (preverbal) clitic (see also example (9)), a phenomenon which is particularly frequent in subordinate clauses. Of the three most interpolated words, adverbs, subject pronouns and negations, the latter is responsable for the mayority of the cases (Chenery 1905: 34) as in: y non se llega a el sino quien es torpe y Io non entiende 'and no one comes near him [= a wicked person] unless he is stupid and does not know' (The Libro de los Buenos Proverbios, chapt. XII, p. 79, 1. 22). Here, the clitic is supposed to lean on the conjunction y, although this element only rarely attracts the clitic to the position before the verb (Gessner 1893: 36-37). It remains unexplained why in such cases the clitic should come to neglect the negation and turn to a much less likely candidate to lean on. For a discussion of this phenomenon and a large body of examples see Chenery (1905) and Ramsden (1963: 134-158). 4. In our corpus of Old Spanish prose texts preverbal clitics are a minority at the beginning of the thirteenth century. In the oldest text examined, La Fazienda de Ultramar (end of the twelfth or beginning of the thirteenth century), the percentage of clitics preposed to a finite verb is 37%. At the end of the thirteenth century we find more or less equal percentages for both preverbal and postverbal clitics (Primera Crdnica General de Espa~a, preverbal: 57%, postverbal: 43%). Some two hundred years later postverbal clitics are clearly outnumbered by their preverbal competitors since the percentage of the last has risen to 87% (Claros Varones de Castilla, 1486). 5. Cf. Rini (1991: 271,279). 6. With 'complex' and 'rather difficult to process' I refer to conceptual complexity rather than syntactical complexity, although the two of course cannot really be separated (see for example fn. 9). 7. In the Spanish text we mark the absence of an explicit subject with O before the Dorien Nieuwenhuijsen 244 finite verb, the subjects which are present are reproduced in bold type. All the finite verbs go in italics. 8. The analysed texts are: La Fazienda de Ultramar, The Libro de los Buenos Proverbios, El Libro de Calila e Digna (ms. A and B), Claros Varones de Castilla, Guerras Civiles de Granada. 9. It is not surprising that subordinate clauses show almost uniform preposition of the clitic (see Table 1). Here, because of the subordination and the consequently wide range of possible relationships involved, for the hearer the information is particularly difficult to process. In our own corpus, in the Fazienda de Ultramar 96% of the clitics in subordinate clauses appears in preverbal position. 10. Notice that (13) shows a direct, logical sequence of the literal remark, the clause between quotation-marks, and the comment dixo. References Barry, A.K. "Clitic pronoun position in thirteenth-century Spanish" Hispanic Review, Spring 55 (2), 1987, pp. 213-220. Bolinger, D.L. "Meaningful word order in Spanish" Boletin de Filologfa (Universidad de Chile), VIII, 1954-1955, pp. 45-56. Chenery, W.H. "Object-pronouns in dependent clauses: a study in Old Spanish word-order" Publications of the Modern Language Association of America XX (1), 1905, pp. 1-151. Contreras, H. A theory of word order with special reference to Spanish, North-Holland Publishing Company, Amsterdam-New York-Oxford, 1976. Diver, W. "Introduction" Columbia University Working Papers in Linguistics, 2 (Fall), 1975, pp. 1-25. England, J. "The position of the direct object in Old Spanish" The Journal of Hispanic Philology, 5 (1), 1980, pp. 1-23. England, J. "Word order in Old Spanish prose: the indirect object" Neophilologus, 67 July (3), 1983, pp. 385-394. Gessner, E. "Das spanische Personal-pronomen" Zeitschrift fiir romanische Philologie, 17, 1893, pp. 1-54. Greenberg, J.H. "Some universals of grammar with particular reference to the order of meaningful elements", in Universals of language (second edition), ed. J.H. Greenberg, The M.I.T. Press, Cambridge, 1966, pp. 73-113. Lapesa, R. Historia de la lengua espafiola, Gredos, Madrid, 1981. Ramsden, H. Weak-pronoun position in the early Romance languages, University Press, Manchester, 1963. Rini, J. "The redundant indirect object constructions in Spanish: a new perspective" Romance Philology, XLV November (2), 1991, pp. 269-286. Texts used for analysis La Fazienda de Ultramar, ed. M. Lazar, Acta Salmanticensia XVIII (2), Salamanca, 1965; ms. end of 12th/beginning of 13th century. El Libro de Calila e Digna, eds. J.E. Keller & R. White Linker, Chisicos Hisp~micos CSIC, Madrid, 1967; ms. A end of 14th century; B end of 15th century. The Libro de los Buenos Proverbios, a critical edition, ed. H. Sturm, The University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 1970; ms. end of 13th/beginning 14th century. P6rez de Hita, G. Guerras Civiles de Granada, ed. S.M. Bryant, Hispanic Monographs, Newark, Delaware, 1982; ms. 1595. La Primera Cr6nica General de Espa~a, I, ed. R. Men6ndez Pidal, Gredos, Madrid, 1955; ms. end of 13th century. Pulgar, F. del Claros Varones de Castilla, Cl~isicos Castellanos, Espasa-Calpe, Madrid, 1942; ms. 1486.