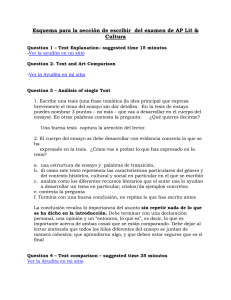

Assessing the Comprehension of Questions in Task

Anuncio