Métodos de la Enseñanza de la Lengua Extranjera

Anuncio

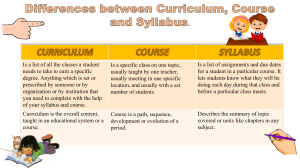

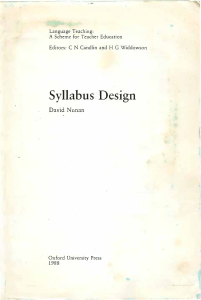

4. MÉTODOS/ENFOQUES DE LA ENSEÑANZA DE LA LENGUA EXTRANJERA B. RECENT APPROACHES This chapter is designed to answer two questions: • What is a functional− notional course and how does it differ from a structural course? • What is meant by communicative approach to teaching foreign languages?. FUNCTIONAL− NOTIONAL COURSES The designer of any language course has to begin by doing two things: choose what items or aspects of the language are to be included and to arrange these pieces of material into the best possible order to ensure successful learning. The former process is called selection, the latter grading. The final arrangement is the language syllabus. The resulting syllabus is known as a structural or grammatical syllabus and can be represented by a list of language forms in a certain order. A functional− notional syllabus is also an arrangement of pieces of language, but these pieces are not language forms: they are all functions and notions. Functions are clear examples of pieces of language content. Basically, a function is a label attached to a sentence saying what it does. But within any such sentence there may be other units of content, which we might call concepts, although they are often, confusingly, referred to as notions. Examples of these are the concepts of time, space, quantity, motion, etc. In practice, unlike functions, these concepts are closely linked to the structure and lexis of the language. But not entirely. The prepositions in, for example, is used both to express time and space: e.g. in the evening and in bed. We should finally add a very important set of concepts representing the speaker's attitude to what he says. ORGANIZATION How might the course organise these pieces of linguistic content into a syllabus?. First, functions are much easier to arrange than concepts or notions. Most existing courses of this kind place emphasis on the communicative functions of language and they tend to be described as functional or functional− notional courses. Secondly, all functional. Notional courses have a strong situational element. obviously functions have to be presented in the language materials contextualized in situations. But some situations, such as using the telephone, have strict conventions that govern the language forms used. Consequently, functional. Notional courses often contain units which are, strictly speaking, situational entitled Using the telephone, asking the way, Making transport enquiries, etc. A general scheme for combining the necessary elements of a notional course might be as follows: The topic element will include provision for a suitable range of lexical items. The situation chosen for presentation purposes will make clear the special reference or appropriacy of the forms chosen to express the functions in question. ADVANTAGES AND DISADVANTAGES OF NOTIONAL SYLLABUS DESIGN Advantages: 1 • Knowledge of structure and lexis is not enough to ensure that the student will be able to communicate effectively when required to do so in any given set of circumstances. A functional− notional syllabus, if well designed, can overcome this problem. • The functional. Notional syllabus enhance motivation. Instead of learning to manipulate language items in a vacuum, the student will be able to recognize the value of the language he learns. • Functional− notional syllabuses are suitable doe specialists courses English for scientists, Disadvantages: • Students must inevitably learn the grammar of the language at some stage. We cannot abandon the principles and procedures of grammatical methods of teaching: we will still have to drill structures and organize the linguistic items into a suitable form of grading. • We are now aiming at subtler uses of language. This makes the tasks of both student and teacher much harder. It could be argued that it might be simpler top aim at more accessible objectives and simply provide our students with the minimum equipment to enable them to cope with most communication tasks, however inappropriate their language would be. • In some ways, the functional− notional syllabus might be very confusing for our students, whereas before they could concentrate on the forms of the language, now they may encounter many different forms under the same heading. All the above points have led many teachers and course writers to consider the functional− notional syllabus more suitable for the intermediate student, who has already covered the basic grammatical syllabus. A functional− notional syllabus could be confusing for the student because of the variety of language forms introduced under one heading has another side to it: that similarities of language form can also be very misleading and confusing. Confusion can result both from the structural and the notional arrangement of language items; it is difficult to say which is more harmful. THE COMMUNICATIVE APPROACH TO LANGUAGE TEACHING The well established procedure for teaching a new pattern has been: presentation, controlled practice and free practice (or production). The teaching policy changes at each of these stages: • At the presentation stage, the teacher is firmly in control and doing most (if not all) of the talking. There is no possibility or error, because the student is not invited to speak. • At the controlled practice stage, the teacher remains in control. The possibility of errors has been reduced to a minimum, but, when that occur, the teacher corrects them until the class produces the form correctly, meaningfully and consistently. At this stage, STT is equal to or greater than TTT. • At the free practice stage, the teacher relaxes control. Mistakes will occur, but students will correct each other or themselves when challenged. STT will be much greater than TTT and the teacher will only intervene if serious problems arise. In reality there is no abrupt shift from one stage to another. There may be a change of the context for practice when shifting from the controlled to the free practice stage, although a good teacher may smooth this transition by providing some thematic coherence in the form of a link in subject matter between the two stages. Alternatively, the free practice stage may occur in a latter lesson altogether: there is no lay which dictates that all three stages should occur in the same lesson. The process is continuum rather than three stages linked together. Once students have been encouraged to produce the new pattern freely and meaningfully, it would be reasonable to introduce a practice activity which gives students a motive and provides them with an opportunity to use their newly acquired language for a purpose. 2 If communicative teaching is teaching language for a purpose, then the sense of purpose needs to play a prominent part in the process of presentation and practice. Instead of teaching forms with their meanings and then going on to practise their uses, we might begin with the use and proceed to teach examples of the forms our students require. This type of procedure might be termed communicative presentation and practice. The main advantage is that, by employing these strategies, the teacher has built up a sense of need in the student for the new language item. When the item is supplied, the student feel a sense of relief; the meaning and use of the item is firmly conveyed and the form is strongly imprinted. The teacher can then go on to practise the pattern in the normal way. The same type of procedure can be applied most effectively to the teaching of language functions. The procedure to be followed here would be like this: • The teacher sets up a communicative activity which demands ability to express the functions to be taught. At this stage, the teacher does not supply the language forms which the students require for the expression of this function. Instead, the students have to cope with whatever language resources they have available. In performing this task they will inevitably produce errors, mistakes • The teacher introduces that required language forms and does sufficient drilling to achieve a reasonable degree of fluency. Since a model of interaction might be the best way to introduce these forms, a suitable way to do this would be to play a taped dialogue illustrating use of the forms and functions to be presented. • The teacher gives students a fresh communication task so as to provide them with an opportunity and motive to use the language forms they have learnt. If serious errors occur, the teacher goes back to the drilling stage again. C. INTEGRATING THE SKILLS WHAT ARE INTEGRATING SKILLS? They are a series of activities or tasks which use any combinations of the form skills: Listening, Reading, Speaking and Writing. They may be related through the topic or through the language, or though both of them. The skills are thus not practised in isolation but in a closely interwoven series of tasks which mutually reinforce and build on each other. WHY INTEGRATE THE SKILLS? There are two main reasons for devising activity sequences which integrate the skills: to practise and extend the students' use of a particular language structure or function and to develop the students' ability in two or more of the four skills within a constant context. There are a number of important advantages in providing students with the kind of integrated skills practice: • Continuity: it allows for continuity in the teaching/learning programme. Tasks and activities are not performed in isolation but are closely related and depend on each other. • Input before output: it helps to ensure that there is input before output. We cannot expect learners to perform a task without orienting and motivating them to what they will be expected to do and providing them with the linguistic means that will enable them to be successful. • Realism: it allows for the development of the four skills within a realistic, communicative framework. The use of such a framework helps to promote awareness not only of how the different skills relate to particular communicative needs, but also of how they led naturally into each other as in real life. • Appropriateness: it gives learners opportunities to recognize and redeploy the language they are learning in different contexts and modes. This help learners to recognize the appropriateness of a particular language form and mode in different contexts and with different participants. 3 • Variety: activities involving all four skills provide variety and can be invaluable in maintaining motivation. • Recycling: it allows naturally for the recycling and revision of language which has already been taught and is therefore often helpful for remedial teaching. It allows for language which is already familiar to the learners to be presented in a variety of new and different ways. • Confidence: it may be helpful for the learner who is weaker or less confident in one particular skill. COMING TO TERMS WITH TESTING 1. Introduction: Testing is an area of English language teaching that many teachers shy away from. It is frequently viewed as a necessary evil, a topic where only experts are competent. Testing can be a positive benefit. I should make it clear at this point that I shall be talking about achievement testing, the sort of testing that takes place at the end of a term, with the aim of checking the learners' learning. 2. Some objections to testing: Those who view testing as a distasteful activity associate it with an older and more authoritarian classroom tradition. Teaching methods have developed, testing as an activity has not been associated with these developments. It is true that in recent years have been innovations in testing techniques. It is not simply a development of new techniques of testing; it might contribute more positively to the development of learners and teachers. To look more closely at why testing is out of accord with the current spirit in English language teaching. In the first place, testing is associated with competition rather than co−operation. Co−operation during a test is condemned as copying. In the same way, testing does not admit of co−operation between teacher and learner. The teacher has switched roles from one who guides to one who confronts. This is a change that many teachers find disagreeable. A response to the absence of teacher− learner co−operation is to introduce co−operation in the preparation for the test. Whether it occurs, such consultation reduces the tension generated by the fear of a known test content. The second reason is that testing is viewed as a competitive activity rather than a co−operative one, then there will be a winner and several losers. Those at the bottom gain little from the experience, and a succession of such experiences may lead them consciously to give up the attempt to learn. The solution to this problem lies in the way in which the texts are marked and the outcome handled. The purpose of classroom achievement testing is to give learner and teacher an idea of what has been learned. 3. The teacher as expert: The chief claim to expertise of this experts is that they are versed in statistics, rather than the production of achievement tests based on what they themselves have taught. A short testing course can only touch inadequately upon statistics in a manner which confirms the expertise of the expert, while leaving teachers convinced of their own ignorance and inability. Many of the procedures of statistical analysis are not appropriate, and that none are essential. Achievement test are not required to discriminate between learners. Whether a classroom achievement test is a good one or not, is a judgement that the classroom teacher is in the best position to make. Many teachers make comments such as I can not test or My tests are awful. These seems an unjustifiably defeatist. Firstly, because as far as the content of a test goes, if teachers know what they are teaching then they must surely know what they can test. Secondly, teaching in the classroom inevitably involve elicitation and assessment of what learners write, say or do. We may consider testing as a 4 more elaborated and structures form of this elicitation and assessment of feedback, which is an element in any teaching. ACHIEVEMENT TESTS: AIMS, CONTENT AND SOME TECHNIQUES 1. Aims: An achievement tests aims to find out how much each student, and the whole class has learned of what has been taught and to provide feed back on students progress to both teacher and students, to show how effectively the teacher has taught and to diagnose those areas which have not been well learned. Tests look back over the syllabus that has been covered and look forward in that they may indicate directions for future remedial work on the class. 2. Content: The content of an achievement test is indicated by each purpose: it must test what has been taught. Some items are more testable than others, so there is a temptation to test what is easier to test rather than received greater emphasis in class. A wide variety of functions, vocabulary, subskills, the test that aims to assess this learning, may last only one class period. This problem can be overcome by including in the test only those items that make up the priorities. Such a solution may be in practical, because the syllabus contains no obvious priorities, or because a need of a more comprehensive picture of the students progress. 3. Some testing techniques: Some items lend themselves more naturally to being tested in certain ways. Some methods of testing are better adapted to testing certain aspects of language learning, and some techniques are more suitable to certain age groups and ways of thinking. Different methods of testing the same skill may well test different subskills. Subjective and objective types involves different kids of language, language learning and methods of marking. Subjective techniques tend to require students to produce longer stretches of language. Objective testing techniques usually require students to recognise or produce a limited range of items in restricted linguistic and situational context. As regards methods of marking, in an objective test, there is only one or a limited number of right answers. This lack of arbitrariness works in the students favour, as it increases a test's reliability, and so guarantees fairness in the assessment of what is tested. In the marking of a subjective test, the marker will often be unsure as to how right an answer is. TESTING FOCUS SUBJECTIVE METHODS OBJECTIVE METHODS Listening • Open− ended questions and answers. • Note taking • Interviews • Blank− filling • Information transfer • Multiple choice questions • True/False questions Speaking • Role plays • Interviews • Group discussions • Describing pictures • Sentence repetition • Sentence responses to cues Reading comprehension 5 • Open− ended comprehension questions and answers • Summary writing • Note taking • Information transfer • Multiple choice questions • True/False questions • Jumbled sentences • Cloze Writing • Guided writing • Free writing • Blank− filling • Sentence joining Grammar • Open− ended sentence completion • Rewriting • Expansion exercise • Scrambled exercise Functions • Giving appropriate responses • Discourse chains • Split dialogues • Matching • Multiple choice questions • Odd man out • Listen and match Vocabulary • Compositions and essays • Paraphrasing • Crosswords • Classifications exercises • Matching exercises • Labelling 4. Which are better, subjective or objective tests? Objective test produce reliable results and focus on accuracy and discrete items, but they provide and assessment of only a limited range of the students' language abilities. Subjective tests can provide information about the students' wider commands of communication, but that information is not always easy to assess in a reliable way. WRITING ACHIEVEMENT TESTS: PRATICAL TIPS 1. Time: Delimitation imposed by the duration of the test, which commonly have to be fitted into one normal− length lesson, necessitates the selection of a valid sample from the structural and functional items and skills included in the syllabus. 2. Coverage: The sample taken from the syllabus is only valid if it accurately reflects the emphasis of the teaching of that syllabus in terms of grammatical and functional items and skills. If fifty per cent of the test involves letter writing when that activity has not been a major item on the syllabus and has taken up only five per cent of class time, then the test is not a valid one. 3. Format: It is important to choose formats which test what they are supposed to test. A written test which involves writing a detailed answer to a given letter may say as much about the students' ability to read as about their ability to write. Student should be familiar with the format use in the test, otherwise poor performance may be due to a misunderstanding of the format rather than to a lack of linguistic competence. 6 4. Difficulty: The level of difficulty of items included in the test should parallel that of the practice activities done by the students during their course. The kind of variation in level of difficulty of test items appropriate to placement or proficiency tests is not necessary in achievement tests. 5. Rubrics: Complex or badly− written instructions can invalidate the tests by misleading students or by terming the instructions into an additional reading comprehension element of the test. It is also advisable to provide an example of an answered test item where the format permits. 6. Marks: The principal point is that the marks should reflect the balance of the syllabus. It should be ensured that important grammatical and functional items on the syllabus are well represented in terms of marks. The weighting of marks must also take into consideration the difficulty of a test item and the proportion of the overall test time that is likely to take students to complete it. TESTING FUNCTIONAL LANGUAGE 1. Introduction This article looks at ways of testing functional language. The methods are listed in random order, they test various aspects of language in use: comprehension, production, degrees of formality and students' understanding of functions as a linguistic concept. 2. Some methods of testing functional language • Read and Match: students are given a list of exponents of the same functions and a parallel list of degrees of formality. Their task is to match the degree of formality with the exponent. • Expanding a discourse chain into a dialogue: Students are given a discourse chain and their task is to make up a dialogue from this chain. • Odd man out: Students have to eliminate one exponent from a list of exponents, either because it is of a different degree of formality or because it is a different function from the others. • Parallel texts− degrees of formality: students are given a dialogue in a formal register. They have to rewrite this text in an informal register. • Appropriate responses: students are given an outline of a situation. Their task is then to write what a person would say in that situation. • Rewriting: students are given a description of a conversation. Their task is to write the conversation. • Written role play: students are given a detailed account of two people's characters, moods and attitudes in a well defined situation. Their task is then to write out the conversation that occurred between these two people. • Multiple choice: students can either choose the best exponent of a function for an outlined situation or choose which degree of formality a given exponent represents. • Split dialogues: students are given the words of one person in a dialogue. Their task is to read the dialogue, then provide the words of the other person. 3. Some implications of these methods Three aspects of functional language tested by these methods are: 7 • The form and meaning of exponents of functions • The degree of formality of exponents of functions • The concept of functions Students need to know not only the form and meaning of an exponent of a function, the sequence of forms it is composed of and its literal meaning, but also its social meaning and appropriateness to different situations. Depending on the age, interests and learning habits of our students, we may find it useful to tell students what a function is doing within a discourse, e.g.: refusing, thanking, congratulating, disagreeing. To do this we need to teach the students the names of the functions. However, particularly with elementary level students, learning the names of the functions can be more complicated than learning the functions themselves. THREE TYPES OF OBJECTIVE TEST 1. Introduction This test types are commonly used because of the speed with which they can be marked, because they involve objective marking, and because of their flexibility. All three can be used to test global and detailed understanding of a test or to focus on specific areas of language, such as grammar and vocabulary. 2. Cloze and gap− filling These two are grouped together because they have a basic operation in common, the substitution by the test writer of individual words in a passage by a space, the student having to write in the missing word or a suitable alternative. This raises the issue of what is and what is not an acceptable words to fill a space, and this can lead to an element of a subjectivity in the marking of this test. Conventional cloze tests involve the removal of words at regular interval, usually every 6−8 words and normally not less than every five. Although these tests should not be too short, there is no such thing as an optimum length. The test writer will need to bear in mind the level of the students taking the test and the amount of time and number of marks to be allotted. When using the regular deletion procedure, it is not usually possible to focus deliberately on selected discrete items because cloze is a purely random means of choosing words for deletion. For this reason cloze tests for use in an achievement test should be carefully chosen so as to ensure that the deleted items all fall within the syllabus followed. The discrete elements tested by cloze are chosen by chance and, if a test writer wishes to test specific language items, then a gap− filling test sometimes refer to as a selective or impure cloze, is more appropriate. 3. True/False tests these can be used to test both reading and listening and the understanding of specific elements of the language. The following points need to be borne in mind when constructing the True/False test and its marking scheme: • In a listening comprehension test, the points refer to by the T−F statements should be adequately spaced through the test so as to give students time to think, mark their answers and return their attention fully to listening before the next tested point arises. • With only two possible answers, there is always the danger of guesswork distorting final marks: students could scored 50% on the exercise without understanding anything. There are three ways of avoiding this element: 8 • By subtracting one mark from a student's total for each wrong answer given • By adding a third element (Don't know) when some of the answer cannot be answered from the text. • By requiring the students to write corrections to the false statements. • Negative T−F statements should normally avoided, as the decision as to whether a negative statement is true or false can lead to confusion. 4. Multiple choice tests As for the above test types, multiple choice can be used to test either global or detail understanding of grammar or vocabulary. Furthermore, it can be used to test the understanding of either single sentences utterances or extended texts. • Vocabulary: the right answer and distractors are given beneath the stem, which has a gap in it. • Reading− listening comprehension: here the right answer and distractors give alternative completions to the stem. • Appropriateness: alternative possible response to the stem are given. • Error recognition: the letter above the part of the sentence which contains an error is to be circled. • Punctuation: entire sentences form alternatives. • Constructing the test: the following points should be borne in mind when constructing a multiple choice test: • It is normal to have four alternative answers for each item. Any fewer than four means that guesswork becomes an important factor. • Instructions should make clear how students are to answer. • The format of each item within each part of the test should be the same. • There should be only one right answer • Vocabulary items should be from the same word class. • Avoid having two distractors with the same meaning, otherwise, if the student is aware of this, the choice will be narrowed to only two options. • Distractors should be approximately the same length, otherwise attention is focused on one option. EXAMPLE OF A TEST 1. Aims and level: The test is focused on intermediate students, and its aims are: • To review the new vocabulary used in this lesson • The check whether they have understood the three conditionals • To make them aware of the differences in use of if, unless, when and in case. • To be aware of the importance of the conditional in the everyday speech. 2. Techniques: • Gap− filling (exercise number one) • Appropriateness (exercise number two) • Discrimination (exercise number three) • Rewriting (exercise number four) • Multiple choice (exercise five) 3. Marking guide: 9 EXERCISE MARKS TIME • First exercise: 10 5 minutes • Second exercise: 20 15 minutes • Third exercise: 25 15 minutes • Fourth exercise: 25 10 minutes • Fifth exercise: 20 10 minutes • Complete the following sentences with if, unless, when or in case: • He got on the train at 8.30 and he'll phone us he gets here. • Please don't phone me at work it is an emergency. • The weather forecast wasn't good. You'd better take this umbrella ... it rains. • She's not sure if she'll free for the party, but she'll let us know she can come. • You won't do well in the exam you work a bit harder. • .. you didn't spend so much on beer, you'd have a lot of money. • Don't forget to send us a postcard . you arrive. • the strikers go back to work at once, the management will dismiss them. • Complete the following conversation with the correct form of the verbs in brackets: • You don't look very cheerful. You haven't failed your driving test again, have you? • Yes, I'm afraid so. But it really isn't fair, you know. I had to take it in a car I wasn't used to. If I (be able).... to use my father's I'm sure I (pass).. • Why didn't you ask me? If (know). You were taking your test, you (can borrow). Mine. Anyway, what happened? • I was coming up to a pedestrian crossing, and had to stop suddenly to let someone over. I didn't have time to look in the mirror, that was all. Just think I (be) all right if that stupid pedestrian (not want) to cross the road. • But surely they didn't fail you for that? • Yes, it's ridiculous, isn't it? And if you think about it, if I (not stop) so quickly, I (may run). him over. And if I (do) .that I (fail).. for sure. But tell me, what (you do). If you (be driving) and that (happen) to you? • I think I (do) just the same. Did you complain? • No, I didn't, and it's too late now anyway. Do you think I (should do).? • If it (be). me, I (would do).. • Maybe, but I'm sure it (not change) anything even if I (make) a fuss. You know how these driving examiners are like. • Complete the following sentences with an appropriate conditional: • I will be very pleased if • I would never hurt an animal unless.... • If I had been born in England... • If I pass the exam, . • Unless I pass the exam, • If I had started playing a musical instrument when I was four years old, now I .... • If you were five years younger, • You can't get a good job unless you ... • Finish the second sentence without changing the meaning: • Take some cash, because the bank might be shut. 10 Take some cash in . • Someone almost certainly saw him leaving the building He must . • They didn't let me stay in the country. I wasn't .. • She made a lot of mistakes because she didn't concentrate hard enough If. • It's ages since I last went to the dentist I .. • She didn't pay very much for her computer The computer. • He couldn't speak just French well, he could write it perfectly too. Not • He started playing football for Manchester United six months ago. He has ... • Will you open the window? he said. He asked me .. • He only ran away from home because he was unhappy. He wouldn't • Choose the best answer between A, B, C or D • If you .. me you were ill, I'd have visited you A. would have told B. Told C. Had told D. wouldn't have • I would have cleaned the house if I .. you were coming A. knew B. would have known C. had known D. have known • Well, I think it's time we.. on our way A. were B. Are C. have been D. will be 11 • I milk chocolate to plain chocolate A. 'd better B. want C. like D. prefer • You.. have seen the Jacobs yesterday− They are in Australia. A. mustn't B. needn't C. can't D. shouldn't • In the last few weeks, a record number of cars A. have been sold B. Have sold C. had sold D. had been sold • I always wear a seat− belt .. I have an accident. A. unless B. If C. in case D. when • . you like what I want to do or not, you won't make me change my mind. A. whether B. When C. because D. if • .. he comes, don't forget to phone me. A. if B. In case C. whether D. that • The accident was your fault− you. Have been driving so fast. A. mustn't B. Wouldn't C. shouldn't D. couldn't LISTENING 1. Procedure: The first part of the lesson are exercises to warm− up, done in order to introduce the listening and the topic. It has two exercises; the first one, is a word association and the second one refers to feed− back. The second part of the lesson has only one exercise, which looks forward to creating a desire to listen. The third part is the listening itself; the first time they will listen to it for general understanding, and the following ones for detail. Then, they will have to say if some statements are right or wrong and to fill in the gaps with the information given in the listening. A possible follow− up activity could be to draw a picture of what they think Mrs Davis street was like, and maybe they could also draw another street of their city. This listening is done with the idea of introducing and reviewing the present perfect tense. 2. Tapescript of the listening: Kelly: How long have you lived in Elm Street, Mrs Davis? Mrs Davis: I've lived here all my life 12 Kelly: Have you lived in that house all that time? Mrs Davis: No, but I've been in this house for fifty years now. Kelly: Where did you live before? Mrs Davis: I was born at number 63 Kelly: Sixty− three? That's next door to me. Mrs Davis: Is it really? That's nice. Well, I lived there till I was twenty− five. When I got married, we moved into number 20 here. Kelly: And you've been here ever since? Mrs Davis: Yes, except for a few months in the war. You see, a bomb fell on the house next door. So I lived at number 63 again for about three months, while they were repairing this one. Kelly: Has the street changed much? Mrs Davis: Ooh, yes! The people have become much richer. They have got cars and televisions. You never saw a car in this street, when I was a girl. Kelly: Do you think life is better now? Mrs Davis: no, not really. It's nice to have the telly, but people have become less friendly. They stay in their own houses all the time. When they go out, they go in their own cars. So you never see anyone. My husband and most of my friends have died now. So it's often very lonely. EXERCISES • You are living in the year 2.000, and you have/use a lot of things your grandparents didn't. What are those things that have changed? Complete the chart below. Grandparents You (Past) (Present) Changes • Games • Transports • Family • Communication • Clothes • School • Jobs 13 • Health • Now, tell the teacher your ideas, and he will write them up on the blackboard. • Where do you think the words below fit best? In the present or in the past? Car Horses Peace Unhealthy Richness Healthy War Radio TV Poverty • Now your are going to listen to Mrs Davis, the oldest person in Elm Street. She has seen a lot of changes in her life. Listen to her attentively. • Right? Wrong? Don't know?. Thick the correct letter. • Mrs Davis lived in another street before she got married. R W D • Mrs Davis has lived in 20 Elm Street all her life R W D • She got married in 1.925 R W D • Kelly lives at number 61 R W D • A bomb fell on Mrs Davis' house in the war R W D • She lived with her parents for three months during the war R W D • She has never seen a car R W D • People in the street are friendlier now R W D • Mrs Davis is 75 years old R W D • Fill in the gaps as you hear Kelly and Mrs Davis talking. • How long have you .. in Elm Street, Mrs Davis? • I'.. lived here all my life. • . you live in that house all that time? • No, but I've . in this house for fifty years now. • .did you live before? • I was born at number .. • Sixty− three? That's next door to me. • Is it ..? That's nice. Well, I lived there till I was When I got married, we moved into .. 20 here. • And you've .. here ever since? • Yes, except for a few in the war. You see, a .. fell on the house next door. So I lived at number.. again for about three ., while they were repairing this one. • Draw a picture of what you think about what Mrs Davis street was like, and another one of your town. WRITING Procedure The first part of the writing lesson is an introduction to the topic they are going to work with: warm− up. It consists on some questions about the five continents, and if they know that they have changed along the time. Then, they will read the text about the prehistoric world, and will collocate the name of the continents left in the drawing. Next, they will complete some sentences with the text given (gap− filling) and will ask questions about the five continents, based on the passage, too. As a follow− up activity, they can be given a chart about the age of reptiles and search the required information in it, in order to complete some sentences. 14 EXERCISES • Do you know how many continents are there? Can you name them?. A lot of years ago they weren't like they are now, they were different; there were different kinds of animals, such as dinosaurs, some strange birds, and so on, that have disappeared. Can you write some sentences explaining what you think the world was like some thousands of years ago?. Below you have some headings that may help you do it: • Animals • Plants • Humans • Climate • Now you are going to read a text which deals with the prehistoric world. Loos at the picture and read the text. Then, answer the questions below: Today, there are seven continents: Europe, Asia, North America, South America, Australasia and Antarctica. But scientists say: Millions of years ago these seven continents were part of two super− continents. The northern continent was called Laurasia and the southern one was called Gondwanaland. Millions of years ago, Europe was next to North America. Both South America and Africa were next to Antarctica. But now they are all far apart. The face of the Earth is still changing. Some continents are still moving a few centimetres every year. Write the name of the other five continents (1−5). There is an extra country (6) that now is part of Asia. Can you write its name too?. • Complete these sentences using the following prepositions: Above Below Between Next to On the left of On the right of • On a modern map Asia is on the right of Europe. Millions of years ago it was.. Europe. • Antarctica is now a long way away from Africa and Australia. But millions of years ago it was .. India and Australia. • India is part of Asia today, but millions of years ago it was not. It was.. Africa and Antarctica. • Today North and South America are thousand of kilometres away from Africa,. But millions of years ago they were.. Africa. • Write questions and answers about the continents using the charts given below: Where was India It was above. below.. between.. next to on the left of.. Asia Europe Africa North were America South America They were 15 on the right of • Complete the sentences. Find the information in the chart below: • The first trees appeared between ... and million years ago. • The first flowers appeared between.. and.million years ago. • The first sharks appeared between and ..million years ago. • The first crocodiles appeared between .and .. million years ago. • The first birds appeared between.and .million years ago. • What was the hottest period? And which one was the coolest? • List some of the mountains that appear in the chart. Date Period (millions of years ago) 350 Carboniferous 280 Parmian 225 Triassic 193 Jurassic 136 Cretaceous 65 Cenozoic Climate and plant life Reptiles and other large animals Hot and wet in northern End of the age of half of the world. Amphibians. Beginning of Gondwanaland cold. First the age of reptiles. trees appeared. Early mammal− like Very warm and dry reptiles. Many kinds of reptiles, including early dinosaurs. Very dry. Many desserts. Large sea− reptiles First flowers appeared. appeared. First crocodiles appeared. Dinosaurs were dominant. Climate humid all over the Giant plant− eaters world (including the North appeared. First birds and and South Poles). sharks appeared. Warm. Two super− Dinosaurs were still continent separated. Andes dominants. Giant meat− Rocky Mountains and the eaters lived. Atlantic Ocean appeared. Cool. Many flowers. Alps End of the Age of an Himalayas appeared. Reptiles. Beginning of the Grass was dominant plant. Age of Mammals. 16