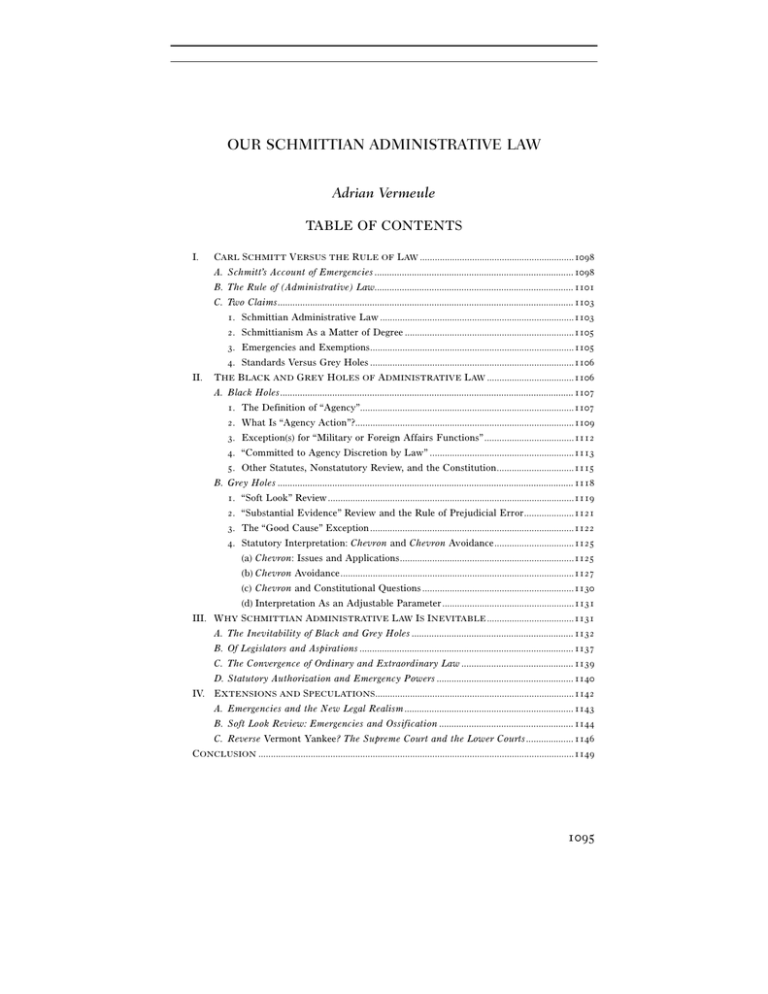

our schmittian administrative law - netdna

Anuncio