Are there factors that predict the result of selective sentinel lymph

Anuncio

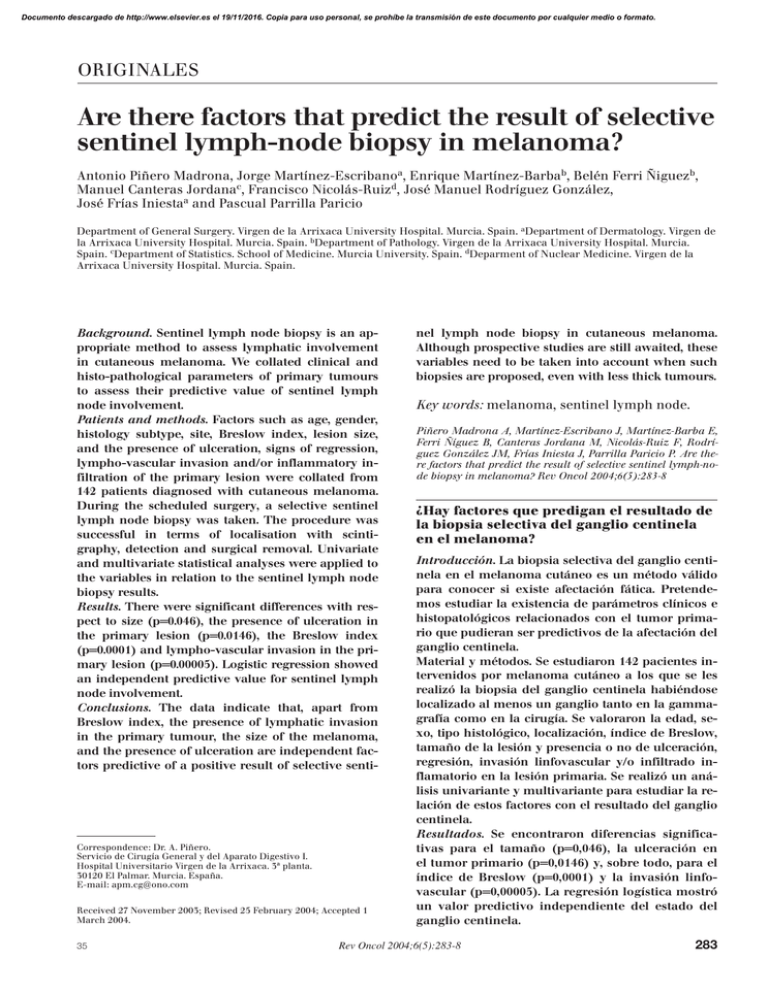

Documento descargado de http://www.elsevier.es el 19/11/2016. Copia para uso personal, se prohíbe la transmisión de este documento por cualquier medio o formato. ORIGINALES Are there factors that predict the result of selective sentinel lymph-node biopsy in melanoma? Antonio Piñero Madrona, Jorge Martínez-Escribanoa, Enrique Martínez-Barbab, Belén Ferri Ñiguezb, Manuel Canteras Jordanac, Francisco Nicolás-Ruizd, José Manuel Rodríguez González, José Frías Iniestaa and Pascual Parrilla Paricio Department of General Surgery. Virgen de la Arrixaca University Hospital. Murcia. Spain. aDepartment of Dermatology. Virgen de la Arrixaca University Hospital. Murcia. Spain. bDepartment of Pathology. Virgen de la Arrixaca University Hospital. Murcia. Spain. cDepartment of Statistics. School of Medicine. Murcia University. Spain. dDeparment of Nuclear Medicine. Virgen de la Arrixaca University Hospital. Murcia. Spain. Background. Sentinel lymph node biopsy is an appropriate method to assess lymphatic involvement in cutaneous melanoma. We collated clinical and histo-pathological parameters of primary tumours to assess their predictive value of sentinel lymph node involvement. Patients and methods. Factors such as age, gender, histology subtype, site, Breslow index, lesion size, and the presence of ulceration, signs of regression, lympho-vascular invasion and/or inflammatory infiltration of the primary lesion were collated from 142 patients diagnosed with cutaneous melanoma. During the scheduled surgery, a selective sentinel lymph node biopsy was taken. The procedure was successful in terms of localisation with scintigraphy, detection and surgical removal. Univariate and multivariate statistical analyses were applied to the variables in relation to the sentinel lymph node biopsy results. Results. There were significant differences with respect to size (p=0.046), the presence of ulceration in the primary lesion (p=0.0146), the Breslow index (p=0.0001) and lympho-vascular invasion in the primary lesion (p=0.00005). Logistic regression showed an independent predictive value for sentinel lymph node involvement. Conclusions. The data indicate that, apart from Breslow index, the presence of lymphatic invasion in the primary tumour, the size of the melanoma, and the presence of ulceration are independent factors predictive of a positive result of selective senti- Correspondence: Dr. A. Piñero. Servicio de Cirugía General y del Aparato Digestivo I. Hospital Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca. 3ª planta. 30120 El Palmar. Murcia. España. E-mail: apm.cg@ono.com Received 27 November 2003; Revised 25 February 2004; Accepted 1 March 2004. 35 nel lymph node biopsy in cutaneous melanoma. Although prospective studies are still awaited, these variables need to be taken into account when such biopsies are proposed, even with less thick tumours. Key words: melanoma, sentinel lymph node. Piñero Madrona A, Martínez-Escribano J, Martínez-Barba E, Ferri Ñíguez B, Canteras Jordana M, Nicolás-Ruiz F, Rodríguez González JM, Frías Iniesta J, Parrilla Paricio P. Are there factors that predict the result of selective sentinel lymph-node biopsy in melanoma? Rev Oncol 2004;6(5):283-8 ¿Hay factores que predigan el resultado de la biopsia selectiva del ganglio centinela en el melanoma? Introducción. La biopsia selectiva del ganglio centinela en el melanoma cutáneo es un método válido para conocer si existe afectación fática. Pretendemos estudiar la existencia de parámetros clínicos e histopatológicos relacionados con el tumor primario que pudieran ser predictivos de la afectación del ganglio centinela. Material y métodos. Se estudiaron 142 pacientes intervenidos por melanoma cutáneo a los que se les realizó la biopsia del ganglio centinela habiéndose localizado al menos un ganglio tanto en la gammagrafía como en la cirugía. Se valoraron la edad, sexo, tipo histológico, localización, índice de Breslow, tamaño de la lesión y presencia o no de ulceración, regresión, invasión linfovascular y/o infiltrado inflamatorio en la lesión primaria. Se realizó un análisis univariante y multivariante para estudiar la relación de estos factores con el resultado del ganglio centinela. Resultados. Se encontraron diferencias significativas para el tamaño (p=0,046), la ulceración en el tumor primario (p=0,0146) y, sobre todo, para el índice de Breslow (p=0,0001) y la invasión linfovascular (p=0,00005). La regresión logística mostró un valor predictivo independiente del estado del ganglio centinela. Rev Oncol 2004;6(5):283-8 283 Documento descargado de http://www.elsevier.es el 19/11/2016. Copia para uso personal, se prohíbe la transmisión de este documento por cualquier medio o formato. PIÑERO MADRONA A, MARTÍNEZ-ESCRIBANO J, MARTÍNEZ-BARBA E, ET AL. ARE THERE FACTORS THAT PREDICT THE RESULT OF SELECTIVE SENTINEL LYMPH-NODE BIOPSY IN MELANOMA? Conclusiones. El análisis de los datos de nuestra serie muestra que, además del índice de Breslow, la presencia de invasión linfática en el tumor primario, el tamaño del melanoma y la presencia de ulceración, son factores predictivos independientes para el resultado positivo de la biopsia selectiva del ganglio centinela en el melanoma cutáneo y, por tanto, a falta de estudios prospectivos, estas variables deben tenerse en cuenta a la hora de indicar la realización de dicha biopsia aun con espesores tumorales pequeños. Palabras clave: melanoma, ganglio centinela. INTRODUCTION To date the most frequently studied prognostic factors in patients with melanoma have been clinical and, particularly, histological, with lymph node involvement and the Breslow index being the most important prognostic factors in the evolution of patients with melanoma1. The most commonly used classification system for staging cutaneous melanoma is the AJCC (American Joint Committee on Cancer), and the main clinical and pathological features of melanoma that predict the risk of metastasis and survival have recently been reviewed by the Committee, who propose a new classification system for patients with melanoma2. In the management of melanoma various studies show that there are no differences in either survival or disease-free time between patients undergoing elective lymphadenectomy and those receiving lymphadenectomy therapeutically3,4. Moreover, lymphadenectomy, as occurs in the treatment of breast cancer, is the surgical intervention that associates most morbidity in the treatment of patients, to the extent that it can interfere significantly in their life quality5. If to this we add the validation by numerous study groups of selective sentinel lymph node biopsy to define the status of lymph node involvement6,7 it is not surprising that this technique is proposed in cases of melanoma, in order to avoid unnecessary lymphadenectomies and provide a better knowledge of the lymphatic drainage routes of the different anatomical regions, which do not always adjust to classical patterns8. Having acknowledged its utility, it would be convenient to increase the efficacy and efficiency of the technique, for which we could intervene, principally, on two fronts: on the one hand by reducing the rate of false negatives with techniques using immunohistochemistry and even molecular biology (PCR of thyrosinase and other proteins); on the other hand, it might be a case of selecting patients for whom an optimum cost-benefit relationship is obtained. 284 The aim of this paper is to study the existence of clinical and histopathological parameters related to primary tumours (cutaneous melanoma) which could be predictors of sentinel lymph node involvement and therefore help improve sentinel lymph node biopsy results in terms of efficacy and efficiency. PATIENTS AND METHODS We studied 142 patients diagnosed with and undergoing surgery for cutaneous melanoma at the Melanoma Unit of the “Virgen de la Arrixaca” University Hospital, in whom a selective sentinel lymph node biopsy proved successful in terms of both scintigraphic location and detection and surgical removal. The search for sentinel lymph nodes was carried out in all cases using a radioactive tracer (Lymphoscint®, Nycomed Amersham Sorin, Milan, Italy), without colouring, by the same surgical team. The following data were recorded in the patients: age, sex, histological type of melanoma, site, Breslow index and lesion size. In the 95 cases referring directly to our health care centre, i.e. not referred from other centres, and in whom we had the possibility of having them assessed independently by the same two pathologists, we also studied the presence or not of ulceration, signs of regression (defined by the presence of vacular fibrous tissue with or without melanophages, and a variable lymphocytic infiltrate), lymphovascular invasion and/or inflammatory infiltrate in the primary lesion. The mean age of the patients was 50.78±15.22 years (range: 13-82); 81 were females (57%) and 61 were males (43%). The most frequent histopathological diagnosis was superficial spreading melanoma (74%); the anatomical distribution is shown in table 1. The number of lymphatic drains per lesion ranged from one to three: single in 116 cases (81.7%), double in 23 cases (16.2%) and triple in 3 cases (2.1%). TABLE 1. Anatomical distribution of the primary lesion Site Trunk Lower extremity Upper extremity Head and neck Cases (%) 55 (38.73) 51 (35.91) 20 (14.08) 16 (11.27) The mean size of the primary lesion was 12.41±7.68 mm (range: 3-46), with a mean Breslow index of 1.81±1.77 mm (range: 0.2-10.3). Sixty-three cases (44.4%) have a Breslow index lower than 1 mm, 28 cases (19.7%) between 1 and 2 mm, 38 (26.7%) between 2 and 4 mm, and 13 cases (9.1%) higher than 4 mm. There was ulceration of the primary lesion in Rev Oncol 2004;6(5):283-8 36 Documento descargado de http://www.elsevier.es el 19/11/2016. Copia para uso personal, se prohíbe la transmisión de este documento por cualquier medio o formato. PIÑERO MADRONA A, MARTÍNEZ-ESCRIBANO J, MARTÍNEZ-BARBA E, ET AL. ARE THERE FACTORS THAT PREDICT THE RESULT OF SELECTIVE SENTINEL LYMPH-NODE BIOPSY IN MELANOMA? 20 of the 95 cases (21%). In 36 (37.9%) there were signs of regression and in 15 (15.8%) evidence of lymphovascular invasion. Focal inflammatory infiltrate was observed in 47 cases (49.5%) and diffuse in 31 (32.6%). In all the cases a histological (hematoxilin-eosine) and immunohistochemical (S-100 and HMB-45) studies of the sentinel node were made. The patients were divided according to whether or not they were positive for sentinel lymph node in the immunohistochemical study (S100, HMB-45); a total of 19 positive cases were found (13.4%), and these were followed up with a lymphadenectomy of the affected area. Of these patients only two have other affected nodes (three and nine more) in addition to the sentinel one. We found three cases of micrometastases that were diagnosed by immunohistochemical techniques. Both metastases and micrometastases were considered positive. A statistical study was conducted to analyse the relationship of each variable to the histopathological and immunohistochemical result of the sentinel lymph node. After verifying adjustment to normality we performed, by way of a univariate analysis, a means comparison with the Student t test for quantitative variables and chi-squared test for qualitative variables. A level of statistical significance was considered for p<0.05. We also performed a multivariate analysis using a logistic regression analysis and calculated the relative risk for the variables with independent predictive value. RESULTS Univariate analysis (table 2): Clinical data (age, sex, site and number of drains per lesion) No differences were found with regard to age or sex between patients with metastatic spread to the sentinel lymph node and those without. Nor did the site of the primary melanoma or the number of lymphatic drains per lesion show differences between the groups. Histopathological data (histological type, lesion size, Breslow index, ulceration, signs of regression, inflammatory infiltrate) The most frequently diagnosed histopathological form was superficial spreading melanoma, seen in 74% of the cases, and although nodular melanoma showed a greater probability of presenting a positive sentinel lymph node, no statistically significant differences were found (p=0.1353). Differences did appear for size (p=0.046) and, particularly, Breslow index (p=0.0001). It must be said here that the minimum values for these parameters, from which positive sentinel lymph nodes were found, were 9 mm Breslow and 9 mm maximum diameter. TABLE 2. Univariate analysis of the different parameters for sentinel lymph node positivity Age (years, mean ± SD) Sex (%) Males Females Size (mm, mean ± SD) Site (%) Trunk Leg Arm Head & neck No. drains (mean ± SD) Diagnosis (%) SSM NM LAM LMM Breslow (mm, mean ± SD) Ulceration (%) Regression (%) Inflammation (%) Focal Diffuse Lymphatic invasion (%) Negative sentinel lymph node (n=123) Positive sentinel lymph node (n=19) p 51.25±14.84 47.78±17.65 0.8327 43.90 56.09 11.95±7.50 36.84 63.16 15.65±8.18 0.5628 38.21 36.58 13.82 11.38 1.19±0.45 42.10 31.58 15.79 10.52 1.30±1.47 75.60 16.26 2.44 5.69 1.56±1.69 16.45 40.5 36.84 63.16 0 0 3.29±1.49 43.75 25 53.16 29.11 3.79 31.25 50 75 0.046 0.9717 0.302 0.1353 0.0001 0.0146 0.2436 0.2146 0.00005 SSM: superficial spreading melanoma; NM: nodular melanoma; LAM: lentiginous acral melanoma; LMM: lentigo malignant melanoma; SD: standard deviation. 37 Rev Oncol 2004;6(5):283-8 285 Documento descargado de http://www.elsevier.es el 19/11/2016. Copia para uso personal, se prohíbe la transmisión de este documento por cualquier medio o formato. PIÑERO MADRONA A, MARTÍNEZ-ESCRIBANO J, MARTÍNEZ-BARBA E, ET AL. ARE THERE FACTORS THAT PREDICT THE RESULT OF SELECTIVE SENTINEL LYMPH-NODE BIOPSY IN MELANOMA? As for the presence in the melanoma of signs of ulceration, regression of lymphatic invasion or inflammatory infiltrate, differences were found for the presence of ulceration in the primary lesion (p=0.0146) together with a greater likelihood that the sentinel lymph node is positive when there is evident lymphovascular invasion in the primary lesion (p=0.00005). As for the existence of inflammatory signs, no differences were found, not even when divided into focal and diffuse (p=0.2146). Multivariate analysis (table 3) The logistic regression of the variables showed parameters with an independent predictive value for sentinel lymph node involvement to be Breslow index (p=0.001), existence of lymphatic invasion (p=0.0005), size of the primary lesion (p=0.003) and, like size, presence of ulceration (p=0.023). TABLE 3. Results of the multivariate analysis using logistic regression Parameter Breslow index* Lymphatic invasion Size** Ulceration p Odds ratio 0.001 0.0005 0.003 0.023 128.7 8.718 2.458 1.987 * Analysis done in relation to the median of the series (0.62 mm). ** Analysis done in relation to 10 mm in diameter. DISCUSSION On the strength of the results in our patients we will comment on the various aspects of the variables studied and whether or not they coincide with findings in other series. Superficial spreading melanoma and nodular melanoma were the two most common histological types, in that order. Although a higher frequency of diagnosed nodular melanoma was observed among patients with a positive sentinel lymph node, the differences were not significant, nor was it a notable independent variable in the multivariate analysis. These results coincide with those reported in other multivariate studies, which do not find histological type to have any independent predictive value; this is because when analysed together with tumour thickness, to which it is closely related, it is seen to have no prognostic value for the same thickness, and the greater aggressiveness of nodular melanomas simply results in thicker lesions9. The anatomical site of the lesion has independent prognostic value in studies conducted with multivariate analyses10,11 and, generally, lesions located in 286 the extremities and, among them, those situated in the upper extremities have a better prognosis than those located in the head, neck, trunk and palmoplantar and subungual areas12. To explain this different prognosis it has been suggested that melanomas located axially may have a later diagnosis, drain to more than one lymphatic territory and have a greater irrigation, which would favour the appearance of metastasis. All the same, our patients did not reveal differences in lymph node involvement according to the site of the primary lesion. In 1970, the thickness of the melanoma began to be quantified using the so-called Breslow index or thickness, considering as such the thickness of the melanoma measured vertically with an ocular micrometer from the highest part of the granulous layer to the deepest part of the tumour13. Numerous multivariate studies have shown that the positive predictive value of other histological parameters is dependent on tumour thickness, especially in stage I melanomas14. This thickness is directly correlated with the likelihood of regional and distant metastases, as well as with survival15. As for the possibility of lymph node spread, our results ratify the importance of tumour thickness, the Breslow index being an independent predictive factor, and establishing at 0.9 mm the minimum value for which sentinel lymph node involvement was found. To give an idea, the risk of lymph node involvement in our series is multiplied by more than 128 when the Breslow index exceeds the median (0.62 mm). With regard to the size of the melanoma, some authors find that tumour volume, calculated from the combination of diameter and Breslow thickness, has a prognostic importance both for overall survival16 and disease-free survival17, and even as a predictive parameter for response to radiation therapy18. In our series, tumour size, represented by the maximum diameter of the primary lesion, had a predictive value for lymph node involvement independent of the other parameters, including thickness. Melanoma ulceration has been reported as a variable related to metastatic lymph node involvement19. It was shown in a series of 8,500 melanomas that the 10-year survival rate in AJCC stage I and II patients with ulcerated lesions was 50%, compared to 70% when there was no ulceration. It was also observed that ulceration, although strongly associated with tumour thickness, had an independent prognostic value10. Moreover, the wider the area of tumour ulceration the worse the prognosis: only 5% of melanoma patients with ulcers larger than 6 mm survive at 5 years, compared to 44% if the ulceration is less than 6 mm20. A relationship was seen in our patients between sentinel lymph node involvement and ulceration, which like tumour size had an independent predictive value. Rev Oncol 2004;6(5):283-8 38 Documento descargado de http://www.elsevier.es el 19/11/2016. Copia para uso personal, se prohíbe la transmisión de este documento por cualquier medio o formato. PIÑERO MADRONA A, MARTÍNEZ-ESCRIBANO J, MARTÍNEZ-BARBA E, ET AL. ARE THERE FACTORS THAT PREDICT THE RESULT OF SELECTIVE SENTINEL LYMPH-NODE BIOPSY IN MELANOMA? The spontaneous regression of a tumour is defined as the partial or complete disappearance in the absence of treatment and has been reported in 10%-58% of melanomas. This variability has been attributed to the different criteria used to define it21. Regression is associated with a poor prognosis in melanomas less than 0.76 mm thick, since more than 20% develop metastasis after a 6-year follow-up, compared to just 2% of those without signs of regression22. One explanation might be that the lesions are thicker before the onset of the regression phenomena. It has been observed that the frequency of histological regression is inversely correlated with the thickness of the lesion: 46% in melanomas with less than 1.5 mm Breslow index, 32% if the index is between 1.5 and 3 mm, and 9% if the thickness is greater than 3 mm23. Shaw et al24 reported that thin melanomas with extensive areas of regression usually had regional lymph node metastases at the time of diagnosis. The same authors speculated that stimulus of the host immune system by malignant cells at the lymphatic tissue could cause the immunological response responsible for the regression of the primary lesion. However, others did not find significant differences for the appearance of metastasis between thin melanomas with or without regression25. We found no relationship between regression in primary cutaneous melanomas and involvement of sentinel lymph nodes. It has classically been accepted that the presence of a mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate at the base of the tumour is a good prognostic factor. However, multifactorial studies have shown that the intensity of the inflammatory response decreases as the thickness of the lesion, with which it is closely and inversely related26, increases, which is why it would not have any independent prognostic value27. The thickness may, at least in part, be conditioned by the infiltrate, i.e. when there is no infiltrate the consequent inability to limit tumour growth may enable it to become thicker. Clemente et al28 find a strong predictive value for survival of the inflammatory infiltrate, with 5- and 10-year rates of 77% and 55% for significant infiltrates, compared to 37% and 27% respectively for the absence of inflammatory infiltrate. In our series regression does not have any predictive value for sentinel lymph node status; in fact, we found a diffuse inflammatory infiltrate associated with a more frequent sentinel lymph node positivity, whereas the presence of a weak focal inflammatory infiltrate was more common in patients with negative sentinel lymph nodes, although in no case were there significant differences. Lastly, lymphatic or blood vessel invasion, defined as the presence of tumour cells in endothelium-lined cavities, is closely related to the existence of satellosis, and although its presence is not invariably linked to the appearance of metastasis, it has been traditionally considered an important predictive factor for 39 the existence of lymph node metastasis29. Its predictive value has recently been shown for lymph node involvement in breast cancer30. Our results confirm these findings and show that the presence of lymphatic invasion or permeation multiplies by 8.7 the risk of sentinel lymph node involvement. In conclusion, analysis of the data in our series shows that apart from Breslow index, the presence of lymphatic invasion in the primary tumour, the size of the melanoma and the presence of ulceration are independent predictive factors for the positive result of selective sentinel lymph node biopsy in cutaneous melanoma, and, although prospective studies are still necessary, these variables must be taken into account when indicating such biopsies with even smaller tumour thicknesses. References 1. Coit DG, Rogatko A, Brennan MF. Prognostic factors in patients with melanoma metastases to axillary or inguinal lymph nodes: a multivariate analysis. Am Surg 1991; 214: 627-36. 2. Balch CM, Buzaid AC, Atkins MB, et al. A new American Joint Committee on Cancer staging system for cutaneous melanoma. Cancer 2000;88:1484-91. 3. Veronesi U, Adams J, Bandiera DC, et al. Inefficacy of immediate node dissection in stage I melanoma of the limbs. N Engl J Med 1977; 297: 627-30. 4. Lens MB, Dawes M, Goodacre T, et al. Elective lymph node dissection in patients with melanoma. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Arch Surg 2002; 137: 458-61. 5. Beaulac SM, McNair LA, Scott TE, et al. Lymphedema and quality of life in survivors of early-stage breast cancer. Arch Surg 2002; 137: 1253-7. 6. Thompson JF, McCarthy WH, Bosch CMJ, et al. Sentinel lymph node status as an indicator of the presence of metastatic melanoma in regional lymph nodes. Melanoma Res 1995; 5: 255-60. 7. Cobben DCP, Koopal S, Tiebosch ATMG, et al. New diagnostic techniques in staging in the surgical treatment of cutaneous malignant melanoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2002; 28: 692-700. 8. Sumner W, Ross M, Lee J, et al. Frequency and significance of lymphatic drainage to unusual sentinel nodal sites in patients with primary cutaneous melanoma. Cancer 2002; 95: 354-60. 9. Mansson-Brahme E, Carstensen J, Erhardt K, et al. Prognostic factors in thin cutaneous malignant melanoma. Cancer 1994;73:2324-32. 10. Balch CM, Soong SJ, Shaw HM, et al. An analysis of prognostic factors in 8.500 patients with cutaneous melanoma. En: Balch CM, Houghton AN, Milton GW, Sober AJ, Soong SJ, editors. Cutaneous melanoma. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott Co., 1992; p. 165-87. 11. Cochran AJ, Elashoff D, Morton DL, et al. Individualized prognosis for melanoma patients. Hum Pathol 2000;31:327-31. 12. Salman SM, Rogers GS. Prognostic factors in thin cutaneous melanoma. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1990;16:413-8. 13. Breslow A. Thickness, cross-sectioned area and depth of invasion in the prognosis of cutaneous melanoma. Ann Surg 1970;172:902-8. 14. Koh HK. Cutaneous melanoma. N Engl J Med 1991;325: 171-82. Rev Oncol 2004;6(5):283-8 287 Documento descargado de http://www.elsevier.es el 19/11/2016. Copia para uso personal, se prohíbe la transmisión de este documento por cualquier medio o formato. PIÑERO MADRONA A, MARTÍNEZ-ESCRIBANO J, MARTÍNEZ-BARBA E, ET AL. ARE THERE FACTORS THAT PREDICT THE RESULT OF SELECTIVE SENTINEL LYMPH-NODE BIOPSY IN MELANOMA? 15. Morton DL, Davtyan DG, Waneck LA, et al. Multivariate analysis of the relationship between survival and the microstage of primary melanoma by Clark level and Breslow thickness. Cancer 1993;71:3737-43. 16. Clark WH, Elder DE, Guerry D, et al. Model predicting survival in stage I melanoma based on tumor progression. J Natl Cancer Inst 1989;81:1893-904. 17. Friedman RJ, Rigel DS, Kopf AW, et al. Volume of malignant melanoma is superior to thickness as a prognostic indicator. Preliminary observation. Dermatol Clin 1991; 9:643-8. 18. Dubben HH, Thames HD, Beck-Bornholdt HP. Tumor volume: a basic and specific response predictor in radiotherapy. Radiother Oncol 1998;47:167-74. 19. Ahmed I. Malignant melanoma: prognostic indicators. Mayo Clin Proc 1997;72:356-61. 20. Slingluff CL. Lethal “thin” malignant melanoma. Ann Surg 1987;208:150-7. 21. Gromet MA, Epstein WL, Blois MS. The regressing thin malignant melanoma. Cancer 1978;42:2282-92. 22. Ronan SG, Eng AM, Briele HA, et al. Thin malignant melanoma with regression and metastases. Arch Dermatol 1987;123:1326-30. 23. Blessing K, McLaren KM. Histological regression in primary cutaneous melanoma: recognition, prevalence and significance. Histopathology 1992;20:315-22. 288 24. Shaw HM, McCarthy SW, McCarthy WH, et al. Thin regressing malignant melanoma: significance of concurrent regional lymph node metastases. Histopathology 1989;15:257-65. 25. Kelly JW, Sagebiel RW, Blois MS. Regression in malignant melanoma: a histologic feature without independent prognostic significance. Cancer 1985;56:2287-91. 26. Day CL, Harrist TJ, Lew RA, et al. Classification of malignant melanomas according to the histologic morphology of melanoma nodules. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1982;8:874-900. 27. Kopf AW, Welkovich B, Frankel RE, et al. Thickness of malignant melanoma: global analysis of related factors. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1987;13:345-9. 28. Clemente CG, Mihm MC, Bufalino R, et al. Prognostic value of tumor infiltrating lymphocytes in the vertical growth phase of primary cutaneous melanoma. Cancer 1996;77:1303-10. 29. Larsen TE, Grude TH. Relation of cross sectional profile, level of invasion, ulceration and vascular invasion to tumor type and prognosis. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1979;87:242-53. 30. Chen M, Palleschi S, Khoynezhad A, et al. Role of primary breast cancer characteristics in predicting positive sentinel lymph node biopsy results. A multivariate analysis. Arch Surg 2002;137:606-10. Rev Oncol 2004;6(5):283-8 40