VECTOR CONTROL PLANNING IN CALIFORNIA Perhaps the best

Anuncio

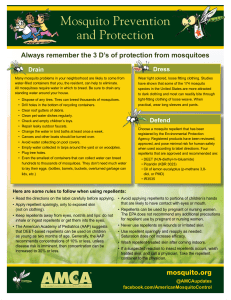

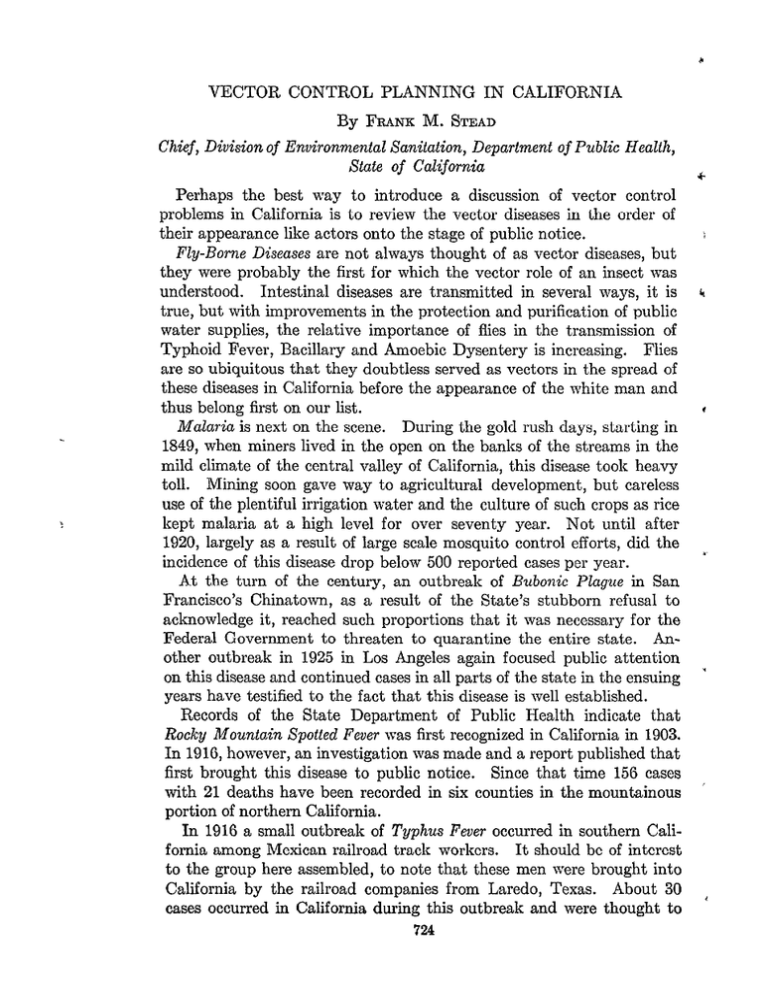

VECTOR CONTROL PLANNING IN CALIFORNIA By FRANK M. STEAD Chief, Divisian oj Environmental Sanitation, Department of Public Health, State of California Perhaps the best way to introduce a discussion of vector control problems in California is to review the vector diseasesin the order of their appearance like actors onto the stage of public notice. Fly-Borne Diseases are not always thought of as vector diseases,but they were probably the first for which the vector role of an insect was understood. Intestinal diseases are transmitted in severa1 ways, it is tme, but with improvements in the protection and purification of public water supplies, the relative importance of ílies in the transmission of Typhoid Fever, Bacillary and Amoebic Dysentery is increasing. Flies are so ubiquitous that they doubtless served as vectors in the spread of these diseasesin California before the appearance of the white man and thus belong first on our list. Malaria is next on the scene. During the gold rush days, starting in 1849, when miners lived in the open on the banks of the streams in the mild cliiate of the central valley of California, this diseasetook heavy toll. Mining soon gave way to agricultura1 development, but careless use of the plentiful irrigation water and the culture of such crops as rice kept malaria at a high leve1 for over seventy year. Not until after 1920, largely as a result of large scale mosquito control efforts, did the incidence of this disease drop below 500 reported casesper year. At the turn of the century, an outbreak of Bubonic Plague in San Francisco’s Chinatown, as a result of the State’s stubborn refusal to acknowledge it, reached such proportions that it was necessary for the Federal Govermnent to threaten to quarantine the entire state. Another outbreak in 1925 in Los Angeles again focused public attention on this diseaseand continued casesin al1parts of the state in the ensuing years have testified to the fact that this disease is well established. Records of the State Department of Public Health indicate that Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever was first recognized in California in 1903. In 1916, however, an investigation was made and a report published that first brought this disease to public notice. Since that time 156 cases with 21 deaths have been recorded in six counties in the mountainous portion of northern California. In 1916 a small outbreak of Typhus Fever occurred in southern California among Mexican railroad track workers. It should be of interest to the group here assembled, to note that these men were brought into California by the railroad companies from Laredo, Texas. About 30 cases occurred in California during this outbreak and were thought to 724 4- I , I ’ ’ < tAugusl1l?48] 1 VECTOR CONTROL 725 be of the epidemic or louseborne type. There were 4 deaths. Starting in 1919, casesof murine or flea-borne typhus began to appear in southern California, and increased in the early twenties, died down during the next decade only to upsurge again in the late thirties in a trend that still is climbing with a peak of 62 casesin 1945 and a similar number since ~ that year. In 1910, a new disease was studied in California and the causative agent identified by the United States Public Health Service. Named , after Tulare County, it was called Tdaremia. This disease has the doubtful distinction of having more animal reservoirs and more modes of transmission than any other vector disease. The number of human cases is not spectacular and the present prospects are not alarming, $ but an increase in contact between humans and wild reservoir animals, such as rabbits, could result in a rapid increase. The disease is by no means confied to its namesake county, but is widely spread throughout the state. Relapting Fever was recognized in California as early as 1921, but , began to attract public notice about 1930, when numerous casesbegan to occur in widely separated mountain resort areas usually at altitudes of*5,000feet or more. Al1 caseswere tick-borne and none fatal. During the past 5 years, the diseasehas increased in occurrence and in the Lake Tahoe area, it has caused suflicient alarm to keep many people away during the vacation season. Most of the casesare contracted in cabins or buildings, especially after opening them in spring and early summer. Epidemic Encephalitis has been a reportable disease in California since 1919 and during the period, 1920 to 1936, from 150 to 75 cases per year were reported in a generally declining trend. In 1937, a Sharp increase occurred and the new caseswere different from the old in severa1 respects. Instead of occurring uniformly throughout the year and throughout the state, they occurred principally during summer and fa11 and were all located in rural areas in the Central Valley. A great increase in case fatality was noted. It has now been definitely established that cases of the new type are mosquito-borne and the most likely vector is the mosquito, C’ulez tarsalis which abounds in the Central Valley of California. Over 100 cases of this disease now occur each year in this area. The last of the actors in this drama to appear on the California stage - is & Fever which broke out last year in Los Angeles County with over one hundred casesand the ink is not yet dry on the reports of initial field investigation of its possible modes of transmission. The mode of attack which the California State Department of Public Health has made on these vector diseasesin the past is as varied as the diseasesthemselves. Fly-borne diseaseshave been approached by the ’ route of sanitation, it being rightly assumed that elimination of the 726 PAN AMERICAN SANITARYBUREAU [Auguel major sources of fly breedmg by proper methods of excreta, manure and garbage disposal would be the most effective approach to the problem. Malaria was early brought under control by the securing of legislation which made possible the establishment of mosquito abatement districts. There are 38 such districts in California today with a total area under control of 16,000 square miles. These districts, although initially established for public health reasons, have so proved their Worth from the economic and comfort standpoint, that they would endure and grow even without the stimulus of the threat or existence of mosquito borne disease. Thus when encephalitis was shown to be mosquitoborne, the health department had its tools ready made and at hand to cope with it. An annual appropriation by the legislature of $400,000 is disbursed by t,he State Department of Public Health to mosquito abatement districts in return for well planned, technically directed, fmancially matched programs, directed at the vectors of malaria and encephalitis. Since 1927, when the outbreak of Plague in Los Angeles indicated that this disease was widespread in California, the Department has carried on one of the most extensive, continuing, endemic surveys on record. Eight field crews, each composed of three men, have hunted, trapped and poisoned rats and ground squirrels in al1 parts of the state. Rodents have been dissected and examined for gross pathology and combed for ectoparasites and hundreds of thousands of specimens of tissue and thousands of pools of ectoparas%eshave been examined in the laboratory with the result that plague endemic foci have been located in hundreds of places in the state. The survey work, in itself, has accomplished a certain degree of control, and intensive spot control work by the Department of Agriculture has been done around areas of positive plague demonstration, but inherently, the program has been one of survey rather than control. No field work, either to discover the foci, or to control the reservoirs or vectors of Rocly Mountain Spotted Fever, has yet been done. An intensive endemic survey for Typhus Fever, however, over a three year period has been conducted in 16 counties of California, involving the examining of 1,731 animals and 157 pools of ectoparasites. This survey has served to define endemic areas in five counties of southern California. During the past frfteen years, endemic studies for Tularemia have been coupled to those for plague, with the result that the extent of establishment of this disease is reliably known. Relapsing Fever endemic areas have been incompletely defined by the occurrence of human cases, until this last fa11when a tick survey was conducted over a considerable portion of the mountainous area above 5,000 feet elevation in the state. c ; w ( * fQ481 VECTOR CONTROL 727 This constituted the picture with respect to vector control activities in the California State Department of Public Health, when on July 1, 1947, the Bureau of Vector Control was established. Prior to this time, activities related to vector control had been spread through many separate bureaus, and coordinated long-range planning in the whole vector field had not been possible. The new bureau had, it is true, a rich heritage, but was given a man-sized job to do. The nucleus of the bureau was formed by pooling the men in the Department who had worked on rodent surveys with those who had engaged in mosquito control studies and relations with mosquito control districts. The field staff now totals 44 men. The first task was to take stock of what was known and what had been done in the past on each of the vector diseases. Certain conclusions were inescapable. The past program looked at as a whole, was lopsided and incomplete. Literally millions of dollars had been spent on endemic surveys of plague, but virtually no studies to adapt techniques of rodent control to California cities had been carried out, and with a few exceptions, no continuing, realistic rodent control programs were in existence in cities. A great deal of time and study on the other hand, had been given to the perfection and demonstration of techniques of large scale mosquito control adaptable to California conditions. Efforts to control encephalitis were crippled by incomplete knowledge of reservoirs and vectors of that disease, and with respect to Q fever we had absolutely no facts to guide a control program. No one knew what the potential threat of Rocky Mountain spotted fever was nor the extent to which relapsing fever had become established. Neither did we know whether chipmunks or bats, for instarme, were important reservoirs of relapsing fever, or whether the diseasecould be effectively attacked by use of DDT against the tick vector. The sudden appearance of Q fever without warning, also pointed up the necessity of being always in a position to meet a new and unexpected situation. In a Word, it was clear that our program must be balanced and highly flexible. To achieve this objective, we established a continuing analysis chart setting forth for each vector disease in relative manner, the current importance as indicated by incidence of disease, and prevalence of reservoir and vector. Deficiencies in fundamental knowledge for some diseases, indicated that the first step needed was research. Successive steps in arder are: endemic surveys, special studies and demonstrations of control techniques, and lastly, stimulation of actual control programs. Recognizmg that we were working in a tremendously broad field with a limited, though sizable staff, we next set ourselves the objective of adjusting our program so that the amount of time and effort put on each disease 728 OFICINA SANITARIA [Agosto PAN-RICANA * is always kept roughly proportional to the current importance which that diseasehas to the people of the state. This meant serious slashing of some activities of many years standing, and the bold embarking on brand new programs. Our planning is therefore largely on a year-byyear basis and in the different diseases, we are in various stages of program development. We are confident, however, that by this approach to our problem, we will escape being caught in the trap of a rigid, crystallized program, and instead, be able to continuously mold our program to serve our needs. For the current calendar year, major emphasis of our vector control program will be four-fold: first, the carrying out of rodent control demonstrations and the stimulation of rodent control programs in cities, largely guided by local departments of health; second continuing demonstrations and program development for the control of the vectors of encephalitis and malaria in the Central Valley of California; third, fundamental investigation to determine the identity and prevalence of vectors of Q fever; and fourth, studies and demonstrations specifically directed toward the control of the insect vectors of relapsing fever, fly-borne diseases,plague and typhus fever. PROYECTO PARA EL CONTROL DE VECTORES CALIFORNIA [Sumario) EN En su trabajo, leído en mesa redonda, hace el A. una breve historia de las enfermedades transmitidas por vectores: malaria, fiebre maculosa de las Montañas Rocosas, tifo, fiebre recurrente, encefalitis y fiebre Q, informando sobre las campañas realizadas por el Departamento de Salubridad del Estado de California para combatir dichos vectores. Existen actualmente en California 38 distritos de lucha contra el mosquito, con una extensión 16,000 millas cuadradas, y al descubrirse que la encefalitis es transmitida por el mosquito, el Depto. de Sanidad asignó la suma de $400,000 anuales para combatir tanto al vector de dicha enfermedad como al del paludismo de la malaria mediante programas bien coordinados. En 1927, al estudiarse un brote de peste en los Angeles, se demostró que Bsta se hallaba extendida en California, lo que condujo a estudios extensos y continuados sobre su endemicidad. En cuanto a la fiebre maculosa de las Montafias Rocosas, nada se ha hecho para descubrir los focos o controlar los reservorios o vectores: en 16 Condados de California se han realizado estudios endémicos sobre tifo por un período de tres años, habiéndose examinado 1,731 animales y 157 mezclas de ectoparásitos, definikndose las zonas endémicas en cinco Condados de California del Sur; durante los 15 años pasados se fundieron los estudios de tularemia y peste, existiendo en la actualidad un conocimiento bastante exacto de esta Gltima; las zonas enddmicas de fiebre recurrente han sido poco definidas por la ocurrencia de casos humanos hasta el otoño pasado en que se efectuó un estudio de garrapatas en una gran porción de la extensión montañosa a una elevaci6n de 5,000 pies. Tal era la situación del Depto. de Sanidad Publica del Estado de California, respecto a vectores, hasta el 1” de julio de 1947 en que se estableció la Oficina de Control de Vectores, la que inició sus labores con un caudal de conocimientos, pero tambi6n haci6ndose cargo de una enorme labor. c c . fW1 CONTROL DE VECTORES 729 Los esfuerzos para controlar la encefalitis se vieron entorpecidos por la falta de conocimiento de los reservorios y vectores de la enfermedad, y con respecto a la fiebre Q no existía absolutamente nada que sirviera de base para un programa de control; nadie conocfa la amenaza potencial que representa la fiebre maculosa de las Montañas Rocosas, ni cuánto se había extendido la fiebre recurrente. El brote repentino de fiebre Q demostró la necesidad de hallarse siempre preparado para hacer frente a situaciones inesperadas; en una palabra, resultó cIaro que el programa debía ser equilibrado y sumamente jlexible, esperando que la actitud sobre el programa no eaiga en el defecto de la rigidez, sino que se adapte continuamente a las necesidades. Este año, nuestro empeño es cuádruple: (l), demostraciones de control de roedores y estímulo de los programas en las ciudades asesorado8 por los departamentos focales de salubridad; (Z), continuación de las demostraciones y programas de control de los vectores de la encefalitis y la malaria en el Valle Central de California; 39, investigación fundamental para determinar la identidad y prevalencia de los vectores de fiebre Q; y 4”, estudios y demostraciones dirigidas específicamente hacia el control de insectos vectores de fiebre recurrente, enfermedades diseminadas por moscas, peste y tifo.