SCOTLAND`S ECONOMIC FUTURE POST

Anuncio

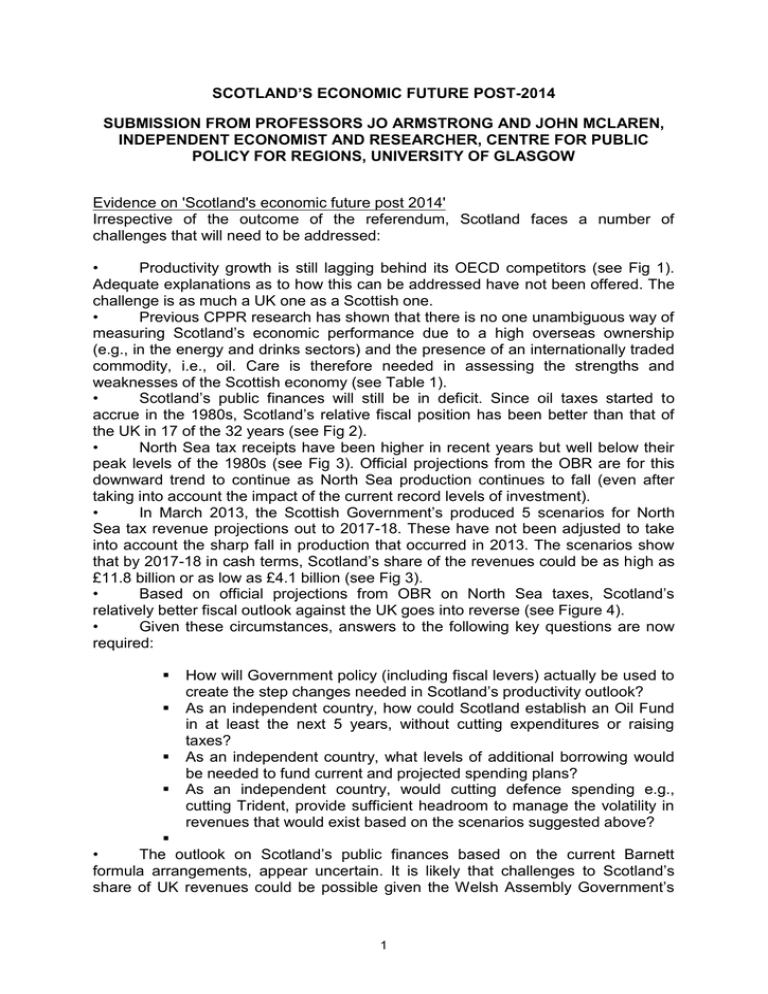

SCOTLAND’S ECONOMIC FUTURE POST-2014 SUBMISSION FROM PROFESSORS JO ARMSTRONG AND JOHN MCLAREN, INDEPENDENT ECONOMIST AND RESEARCHER, CENTRE FOR PUBLIC POLICY FOR REGIONS, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW Evidence on 'Scotland's economic future post 2014' Irrespective of the outcome of the referendum, Scotland faces a number of challenges that will need to be addressed: • Productivity growth is still lagging behind its OECD competitors (see Fig 1). Adequate explanations as to how this can be addressed have not been offered. The challenge is as much a UK one as a Scottish one. • Previous CPPR research has shown that there is no one unambiguous way of measuring Scotland’s economic performance due to a high overseas ownership (e.g., in the energy and drinks sectors) and the presence of an internationally traded commodity, i.e., oil. Care is therefore needed in assessing the strengths and weaknesses of the Scottish economy (see Table 1). • Scotland’s public finances will still be in deficit. Since oil taxes started to accrue in the 1980s, Scotland’s relative fiscal position has been better than that of the UK in 17 of the 32 years (see Fig 2). • North Sea tax receipts have been higher in recent years but well below their peak levels of the 1980s (see Fig 3). Official projections from the OBR are for this downward trend to continue as North Sea production continues to fall (even after taking into account the impact of the current record levels of investment). • In March 2013, the Scottish Government’s produced 5 scenarios for North Sea tax revenue projections out to 2017-18. These have not been adjusted to take into account the sharp fall in production that occurred in 2013. The scenarios show that by 2017-18 in cash terms, Scotland’s share of the revenues could be as high as £11.8 billion or as low as £4.1 billion (see Fig 3). • Based on official projections from OBR on North Sea taxes, Scotland’s relatively better fiscal outlook against the UK goes into reverse (see Figure 4). • Given these circumstances, answers to the following key questions are now required: How will Government policy (including fiscal levers) actually be used to create the step changes needed in Scotland’s productivity outlook? As an independent country, how could Scotland establish an Oil Fund in at least the next 5 years, without cutting expenditures or raising taxes? As an independent country, what levels of additional borrowing would be needed to fund current and projected spending plans? As an independent country, would cutting defence spending e.g., cutting Trident, provide sufficient headroom to manage the volatility in revenues that would exist based on the scenarios suggested above? • The outlook on Scotland’s public finances based on the current Barnett formula arrangements, appear uncertain. It is likely that challenges to Scotland’s share of UK revenues could be possible given the Welsh Assembly Government’s 1 concerns they are receiving an inequitable allocation assessed on need. As North Sea tax revenues fall, Scotland continuing to receive a higher per capita share via Barnett may well require to be defended. Should Scotland remain a part of the UK, what would adjusting the Barnett funding arrangement to accommodate external challenges mean for Scotland’s public finances? Fig 1: Gap between Scotland and lowest ranked country in the OECD top quartile (percentage points) Source: Scottish Government, Scotland Performs; the Scottish Government’s target is for Scotland to rank in the top quartile for productivity against key trading partners in the OECD by 2017. 2 Fig 2: Net Fiscal Balance, Scotland & UK, % of GDP - Actual Source: GERS 2013 Fig 3: Total North Sea tax revenues, £ billion (2011-12 prices) Source: Historic data from ONS; projections from Scottish Government, March 2013 3 Fig 4: Net Fiscal Balance, Scotland & UK, % of GDP - Projections Source: CPPR, 2013 Table 1: Scottish and UK GDP growth rates, at basic prices, per annum, 2001 to 2011 Scotland UK Scotland minus UK % points CASH TERMS* 1 GDP inc oil and gas 4.5 - 4.7% 4.0% 0.5 – 0.7% 2 GDP exc oil and gas 4.1 - 4.4% 4.0% 0.1 - 0.4% Population growth 0.4% 0.7% -0.3% 3 GDP per capita, inc oil 4.0 - 4.2% 3.3% 1.0 – 1.2% and gas 4 GDP per capita, exc oil 3.7 - 3.9% 3.3% 0.4 - 0.6% and gas REAL TERMS** 5 GDP (official) 1.5% 1.5% 0.0% Comparable: 6 GDP (inc oil & gas) -0.3 to -0.5%*** 1.5% -1.8 to -2.0% 7 GDP (exc oil & gas) 1.5% 1.8% -0.3% 8 GDP per capita (official) 1.1% 0.8% 0.3% Comparable: 9 GDP per capita, (inc oil & -0.7 to -0.9%*** 0.8% -1.5 to -1.7% gas) 10 GDP per capita, (exc oil 1.1% 1.1% 0.0% & gas) *The range shown for Scottish cash terms growth rates covers data published in both (i) the Regional National Accounts and (ii) by the Scottish Government (SNAP accounts). 4 **Under real terms, row 5 (and implicitly row 8) shows the growth rates as published by the Scottish Government for Scotland and the UK, where all North Sea activity is allocated to the UK but none to Scotland. By contrast, all other rows which include North Sea output apportion a geographic share of North Sea output to Scotland. ***This range has been calculated using approximations for North Sea growth and output based on UK GDP data. Sources: Scottish Government: ‘Gross Domestic Product 3rd Quarter 2012’, Tables 2a and 2b; National Records of Scotland – ‘2011 Census: First Results on Population estimates for Scotland; ONS, ‘2011 Census: Population Estimates for the UK’; UK Blue Book 2012; SNAP Quarterly National Accounts tables – 2012 Quarter 3; ONS Regional GVA annual publication 2013. For a more detailed analysis of this table see Scotland's Economic Performance and the Fiscal Implications of Moving to Independence, National Institute Economic Review, February 2014, vol. 227 no. 1 Professor Jo Armstrong Professor John McLaren March 2014 5