Zigzag Zaha - Arquitectura Viva

Anuncio

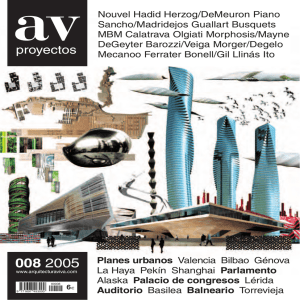

Primavera Spring Zigzag Zaha Zigzag Zaha El premio Pritzker 2004 ha distinguido a Zaha Hadid, la iraquí afincada en Londres cuyo lenguaje diagonal o sinuoso es tan singular como su figura. The 2004 Pritzker Prize has distinguished Zaha Hadid, the London-based Iraqi whose diagonal or wavy architectural language is as characteristic as her figure. 250 2005 AV Monografías 111-112 M ÁS ARTISTA que arquitecta, y más personaje que artista, Zaha Hadid es la encarnación rotunda de la diva. Temperamental y desbordante, su voluminosa figura envuelta en túnicas plisadas de Issey Miyake se impone con una presencia física que irradia aplomo y energía contenida. Sobre zapatos imposibles, y ornamentada con bolsos y joyas que quitan el hipo, la iraquí afincada en Londres transmite una seguridad en sí misma que sólo puede provenir de quien ha construido su imagen con tanto empeño como su propia obra. Desde la época juvenil en que se ataviaba con innumerables gasas laboriosamente sujetas con decenas de imperdibles, Zaha —como es universalmente conocida— ha hecho de su persona un proyecto artístico tan significativo como el formado por sus pinturas, dibujos, escenografías y diseños: un camino ya explorado por Dalí, Warhol o Beuys, pero menos común en el universo profesional de la arquitectura. Elevada al estatus de icono mediático, recibió el año pasado el premio Mies por una zigzagueante marquesina de hormigón en Estrasburgo que realizó invitada a título de artista, y obtiene éste el premio Pritzker por una trayectoria más rica en representaciones visionarias que en obras construidas. Nada de esto, sin embargo, disminuye el mérito de la galardonada o hace polémica su elección: el unánime reconocimiento de su talento plástico hizo de Zaha, “irónicamente, una opción segura” en el Mies, como comentó el presidente del jurado, David Chipperfield; y su condición de mujer y su origen árabe, unida a su popularidad entre los estudiantes —destacada en las motivaciones del jurado del Pritzker—, la convierten en una candidata tan políticamente irreprochable como conviene al premio americano (por más que su concesión a «Zaha Hadid from Great Britain» cuando las tropas británicas siguen en Irak se preste a otras lecturas). En esta convocatoria se incorporaron al jurado del premio Pritzker, en sustitución de los fallecidos J. Carter Brown y Giovanni Agnelli, dos miembros nuevos: el presidente de Vitra, Rolf Fehlbaum, un fabricante de muebles de autor y promotor de arquitecturas de vanguardia que fue el primer cliente de Zaha; y la directora editorial de Phaidon en Nueva York, Karen Stein. Ambos nombres refuerzan el peso en el premio del diseño y los medios de comunicación, dando un protagonismo a la publicidad y la imagen en sintonía con el momento del mundo, y haciendo más inteligible su decisión. Por decimotercer año consecutivo, el Pritzker elude la arquitectura americana, prolongando la ausencia en el galardón de Peter Eisenman, un autor cuyo talante experimental ha dificultado su reconocimiento profesional, pero que tras la inclusión en el palmarés de Koolhaas en 2000 y Zaha ahora sólo puede explicarse por alguna testaruda animadversión. Avalada por un premio de esta trascendencia y con el combustible del aluvión de proyectos que actualmente se aglomera en su estudio, la verdadera carrera de Zaha se inicia ahora. De manera apropiada, la arquitecta recibirá la medalla en San Petersburgo, en la misma Rusia donde se gestaron muchas de las experiencias constructivistas y suprematistas —de El Lissitzky a Malevich— que alimentaron su formación londinense, por no hablar de los lienzos de Liubov Popova, cuyas formas geométricas translúcidas, derivadas del cubismo analítico, se prolongan en los ‘dibujos de rayos X’ de Zaha. La autora de paisajes cristalográficos y topografías fracturadas que demandaba al ingeniero Peter Rice «lo quiero todo torcido», propone hoy sin embargo espacios que fluyen y se penetran sobre territorios de metacrilato, reemplazando el ángulo agudo por la curva, el zigzag por el spaghetti, y las colisiones por los flujos. Seguirá haciendo flotar el hormigón, enredando rampas o agrupando columnas delgadas como bastones de lluvia; pero su vocabulario plástico estará desde ahora al servicio de su empeño por construir una arquitectura líquida. De los pilares oblícuos de Estrasburgo (abajo) a las formas fluidasdel proyecto para el Centro de Arte Contemporáneo en Roma (página anterior), Zaha hace del zigzag el signo peculiar que abrevia el croquis para Cincinnati (izquierda). M than an architect, and more a personality than an artist, Zaha Hadid is the rotund embodiment of the diva. Temperamental, overwhelming, her voluminous figure wrapped in pleated Issey Miyake tunics is a physical presence irradiating aplomb and contained energy. On impossible shoes and decked with breathtaking jewels and bags, the London-based Iraqi transmits the self-confidence of one who has built her image as determinedly as her work. Since the old days when she dressed herself up in innumerable gauzes painstakingly held together with dozens of safety pins, Zaha – as she is widely known – has made of her person an artistic project that is as significant as that which consists of her paintings, drawings, stage sets, and designs: a road previously explored by Dalí, Warhol, or Beuys, but less commonly in the professional world of architecture. Elevated to the status of a media icon, last year she received the European Union Mies van der Rohe Award for a zigzagging concrete canopy over an intermodal terminal in Strasbourg that she was commissioned to build as an invited artist, and this year she wins the Pritzker Prize for a career where visionary representations outnumber actual built works. None of this diminishes the merit of the ORE AN ARTIST awardee or makes her victory polemic: unanimous recognition of her sculptural talent made Zaha, “ironically, a sure option” in the Mies, said jury president David Chipperfield; and her being a woman and of Arab origin, along with her popularity among students, which was highlighted among the motivations of the Pritzker jury, turned the architect into as politically irreproachable a candidate as befits the American prize (however much its going to “Zaha Hadid from Great Britain”, at a time when there are still British troops in Irak, lends itself to other symbolic readings). This year, in place of the late J. Carter Brown and Giovanni Agnelli, the Pritzker jury counted two new members: Rolf Fehlbaum, president of Vitra, manufacturer of signature furniture and promoter of avant-garde architectures and, as such, Zaha’s first client; and Karen Stein, editor of Phaidon in New York. Both names add weight to design and the media in the prize, giving importance to publicity and image, in tune with the spirit of the times, and thereby making the jury’s decision more readily intelligible. For thirteen consecutive years now the Pritzker has stayed clear of American architecture, prolonging the absence in the hall of fame of Peter Eisenman, an author for whom professional recog- From the oblique columns of Strasbourg (below) to the flowing forms of the Contemporary Arts Center project in Rome (previous page), Zaha turns the zigzag into a distinctive feature, as abridged in the sketch for Cincinnati (left). nition has been hindered by his experimental and critical inclinations. With Koolhaas’ winning the prize in 2000 and Zaha’s capping it now, however, the delay of Eisenman’s Pritzker can only be attributed to some stubborn animadversion. Endorsed by a trophy of such significance and inundated with projects, it is now that the real career of Zaha takes off. Appropriately, the architect is to receive a medal in St. Petersburg, in the same Russia where, from El Lissitzky to Malevich, many of the constructivist and suprematist experiments that nourished her London training were initiated, not to mention the canvases of Liubov Popova, whose translucent geometric forms, derived from analytical cubism, are prolonged in Zaha’s ‘X-ray drawings’. The author of crystallographic landscapes and fractured topographies who urged the engineer Peter Rice to make everything at an angle now proposes spaces that flow over and penetrate territories of methacrylate, replacing acute angles with curves, zigzags with spaghetti, and collisions with fluxes. She will continue to make concrete float, tangle up ramps, or orchestrate sheaves of slender columns diagonal like the rain. But her aesthetic vocabulary will from now on be at the service of a determination to build a liquid architecture. AV Monographs 111-112 2005 251