98-98(8) (Curvas de índice...)

Anuncio

CURVAS DE ÍNDICE DE SITIO DE FORMA Y ESCALA VARIABLES EN

INVESTIGACIÓN FORESTAL

VARIABLE FORM AND SCALE SITE INDEX CURVES IN FOREST RESEARCH

Juan M. Torres-Rojo

Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas. División de Economía. Carr. México-Toluca Núm.

3655 Col. Lomas de Santa Fé. 01210, México D. F. (juanmanuel.torres@cide.edu)

RESUMEN

ABSTRACT

Las curvas de índice de sitio pueden ser anamórficas o polimórficas

y ambas tienen propiedades complementarias. De aquí que las

curvas de índice de sitio que presenten las propiedades de ambos

tipos de curvas se convierten en una herramienta importante para

mejorar las estimaciones de altura del rodal y productividad forestal. Este artículo presenta un procedimiento para generar curvas de índice de sitio compuestas, con parámetros de forma y escala variables. Tal estimación incorpora efectos de cambio de forma

y escala en las curvas de índice de sitio. Estas curvas se generan al

suponer cambios discretos o continuos en la relación altura-edad

para el intervalo de interés. En ambos casos las funciones presentan las ventajas tradicionalmente asociadas a las funciones

anamórficas y polimórficas. El análisis de datos empíricos mostró

que la bondad de ajuste de estos modelos es similar a los ajustes

obtenidos con las formas anamórficas o polimórficas derivadas de

modelos con mayor número de parámetros. Una prueba de validación mostró que las curvas de índice de sitio compuestas proporcionan mejores predicciones sólo en el caso de tener diferencias de edad muy pequeñas.

Usual site index curves are either anamorphic or polimorphic and

both have complementary properties. Hence, site index curves

having properties from both types of curves become an important

tool for the improvement of height and productivity estimates. A

procedure to generate composed site index curves with variable

shape and scale parameters is presented in this paper. Such an

estimation incorporates effects of shape and scale changes in the

site index curves. These curves are generated by assuming either

discrete or continuous changes for the height-age relationship

within the interval of interest. In both cases the composed curves

present advantages traditionally attached to polimorphic and

anamorphic curves. Analysis of empirical data showed that the

goodness of fit of these models is similar to fits obtained from

anamorphic or polimorphic forms derived from models with a

larger number of parameters. A validation test showed that

composed site index curves yield better predictions for site index

than traditional models only when there are very small age

differences.

Key words: Ana-polimorphic curves, poli-anamorphic curves,

validation test, dominant height-age relationship.

Palabras clave: Curvas ana-polimórficas, curvas poli-anamórficas,

prueba de validación, relación altura dominante-edad.

INTRODUCTION

INTRODUCCIÓN

I

n recent years site indexes have become the most

popular and practical method to evaluate forest

productivity. This method consists on evaluating the

height that dominant or co-dominant and healthy trees

would attain at a predetermined age, frequently referred

to as base age or index age (Payandeh and Wang, 1994).

Such evaluation requires the assumption of a model that

represents the height-age relationship, as well as the

assumption for the behavior of the family of curves

generated under the same model.

The form of the family of site index curves has been

divided into two types: anamorphic and polymorphic

(Clutter et al., 1983). The first one is characterized because

the height keeps the same proportion at different ages,

and for that reason the curves seem to have the same shape.

On the contrary, polymorphic curves can be of two

different kinds: disjoint and nondisjoint; in both cases

E

n años recientes los índices de sitio se han convertido en el método más popular y práctico para

evaluar la productividad forestal. Este método

consiste en evaluar la altura que lograrían los árboles

dominantes o codominantes y sanos a una edad predeterminada, frecuentemente referida como edad base o edad

índice (Payandeh y Wang, 1994). Tal evaluación requiere la suposición tanto de un modelo que represente la

relación altura-edad, como de un comportamiento de la

familia de curvas generadas bajo el mismo modelo.

La forma de la familia de curvas de índice de sitio se

ha dividido en dos clases: anamórfica y polimórfica

(Clutter et al., 1983). Las primeras se caracterizan por

Recibido: Septiembre, 1998. Aprobado: Agosto, 2000.

Publicado como ENSAYO en Agrociencia 35: 87-98. 2001.

87

88

AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 35, NÚMERO 1, ENERO-FEBRERO 2001

que la altura guarda la misma proporción a diferentes

edades, por lo que las curvas aparentan tener la misma

forma. Por el contrario, las curvas polimórficas pueden

ser de dos tipos: con intersecciones y sin intersecciones;

en ambos casos la proporción que guarda la altura es diferente entre curvas, y por tanto éstas aparentan diferente

forma en cualquiera de sus dos variantes.

Desde que se inició el uso de los índices de sitio como

medidas de productividad de terrenos forestales, también

empezó la polémica entre el uso de curvas anamórficas o

polimórficas. A la fecha nadie puede argumentar sobre la

superioridad real de alguna de ellas, dado que su uso prácticamente depende de la especie en cuestión (Payandeh,

1977; Hahn y Carmean, 1982), detectándose que algunas ventajas de un tipo de curva se convierten en desventajas para el otro tipo y viceversa. Se ha planteado la hipótesis de que la integración de variaciones tanto en forma como en escala de las curvas de índice de sitio podría

dar por resultado un tipo de curva que mezcle las ventajas de ambas. Así, se ha señalado que las curvas

anamórficas asemejan el comportamiento teórico esperado de curvas de índice de sitio; sin embargo, en años

recientes se ha descubierto que varias especies presentan

el tipo de curva polimórfico en su relación altura-edad

(Newnham, 1988; Ker y Bowling, 1991; Stansfield et al.,

1991; Goelz y Burk, 1992; Payandeh y Wang, 1994).

Dado este marco de referencia, convendría integrar

tanto el componente anamórfico como el polimórfico en

una función de índice de sitio, la cual podría llamarse

ana-polimórfica o poli-anamórfica. Tal integración consistiría en combinar los cambios en forma y escala de

una función cualquiera que relacione las variables altura-edad. La derivación de una función o una metodología que proporcione funciones con tales características,

sería útil en los estudios de productividad y crecimiento,

pues mejoraría la calidad de las estimaciones de crecimiento en altura.

Este trabajo presenta una alternativa metodológica

para desarrollar curvas ana-polimórficas o polianamórficas, mismas que en lo sucesivo se denominarán

“Curvas compuestas”.

the height proportion is different among curves, and

therefore they show different shapes in any of its two

variants.

Since site indexes have been used as a productivity

measure for forestlands, the controversy over using

anamorphic or polymorphic curves began. Even now,

nobody can argue the superiority of either of them, since

their use depends basically on the species (Payandeh,

1977; Hahn and Carmean, 1982), noticing that some

advantages of one type of curve become disadvantages

for the other type and viceversa. The hypothesis of how

the integration of variations in shape and scale on site

index curves could result in a type of curve that

encompasses the advantages of both has been proposed.

In this way, it has been pointed out that anamorphic curves

have a similar theoretical behavior to the expected one

from site index curves; however, in recent years it has

been found that a variety of species have the polymorphic

curve height-age relation type (Newnham, 1988; Ker and

Bowling, 1991; Stansfield et al., 1991; Goelz and Burk,

1992; Payandeh and Wang, 1994).

Given this framework, it would be convenient to

integrate the anamorphic component and polymorphic

component in a single site index function, which could

be named ana-polymorphic or poly-anamorphic. Such

integration would consist on mixing the changes in shape

and scale of any function that relates the variables height

and age. The derivation of a function or methodology

that produces such functions would be helpful in

productivity and growth studies because it would improve

the quality of growth-height estimates.

This paper presents an alternate methodology to

develop ana-polymorphic or poly-anamorphic curves,

which from here on will be called “Composed curves”.

VARIABLE SHAPE AND SCALE PARAMETER MODEL

To illustrate the ana-polymorphic function derivation, assume a

simple function (Schumacher, 1939) which relates the variables height

and age

ln(h) = a + b / E

(1)

MODELO CON PARÁMETROS DE FORMA

Y ESCALA VARIABLES

Para ilustrar la derivación de la función ana-polimórfica supóngase

una función simple (Schumacher, 1939) que relacione las variables

altura-edad

ln(h) = a + b / E

(1)

donde h representa altura, E la edad, a y b son los parámetros del

modelo y ln(.) indica el logaritmo natural. Si se considera que el Indice de Sitio (IS) se define como la altura que se logra a la edad base

where h represents height, E representes age, a and b are model

parameters and ln(.) represents the natural logarithm. If we define the

Site Index (IS) as the height reached at the base age (Eb), then it is

possible to estimate the IS with the same functional form trough the

relationship:

ln(IS) = a + b / Eb

(2)

The traditional procedure to develop site index curves from Model

2, initially requires an assumption on the shape of the family of curves.

Assume that the site index form we wish to obtain is of the anamorphic

TORRES-ROJO: CURVAS COMPUESTAS DE ÍNDICE DE SITIO EN INVESTIGACIÓN FORESTAL

(Eb), entonces es posible estimar el IS con la misma forma funcional a

través de la relación:

ln(IS) = a + b / Eb

(2)

El procedimiento tradicional para construir familias de curvas de

índice de sitio a partir del Modelo 2, inicialmente requiere de la suposición de la forma de la familia de curvas. Supóngase que la forma de

índice de sitio que se desea obtener es del tipo anamórfico, lo que

implica que las curvas deben tener la misma forma, por lo que el

parámetro de escala a se supondrá variable, mientras que el parámetro

de forma (b ) permanecerá constante (lo que garantiza la misma forma). Al despejar a de (1), se obtiene la función que muestra la variación de a con cambios en edad y altura:

a = ln (h) - b / E

(3)

Al sustituir (3) en (2) se obtiene la siguiente función anamórfica

de índice de sitio para el Modelo 1:

ln(IS) = ln(h) + b (1 / Eb - 1 / E)

(4)

En esta función el parámetro de forma b es constante; sin embargo sería posible suponer una variación de este parámetro dentro del

intervalo de estimación del índice de sitio, al considerar el cambio

incremental de b. Este cambio podría integrarse a (4) como:

ln(IS) = ln(h) + b (1 / Eb - 1 / E) + db (1 / Eb - 1 / E)

89

type, which implies that the curves must have the same shape, hence

we assume that the scale parameter a is variable, and that the shape

parameter (b) remains constant (which ensures the same shape). From

(1), we obtain a function that shows how a changes when age and

height change:

a = ln (h) - b / E

(3)

Substituting (3) into (2) we obtain the following anamorphic site

index function for Model 1:

ln(IS) = ln(h) + b (1 / Eb - 1 / E)

(4)

In this function the shape parameter b holds constant; however, it

would be possible to suppose a variation in this parameter within the

site index estimation interval by considering an incremental change

on b. This change could be integrated into (4) yielding:

ln(IS) = ln(h) + b (1 / Eb - 1 / E) + db (1 / Eb - 1 / E)

(5)

where db shows the change in the shape parameter within the age

interval (E - Eb ) and the height interval (h - IS ), that is, db is the

total differential of b with respect to height and age variables.

Solving Model 1 for b it is possible to obtain the total differential

db, which yields:

af

af

db = Ed ln h + ln h - a dE

(5)

donde db muestra el cambio en el parámetro de forma dentro del intervalo de edades (E - Eb ) y el intervalo de alturas (h - IS ), esto es,

db es la derivada total de b con respecto a las variables altura y edad.

Substituting the d[ln(h)] and dE values by the ones we would

obtain considering the differences within the estimation interval, db

could be re-written as:

Al despejar b del Modelo 1 es posible obtener el valor de db por

una simple derivada total, la cual tomaría la siguiente forma:

db = E ln IS - ln h + ln h - a Eb - E

af

Al sustituir los valores de d[ln(h)] y dE, por los que se obtendrían

al considerar las diferencias en el intervalo de estimación, db se puede

reescribir como:

af

b

b

a f RS 2EE- E UV{lnahf + b- Elnahf+ lnahf - a

T

W

1

/

1

/ Eq

E

l

ln IS =

b

b

Eb - E

}

(7)

(6)

Al sustituir (6) en (5) y rearreglando se obtiene la siguiente función de índice de sitio:

a f RS 2EE- E UV{lnahf+ b- Elnahf + lnahf- a

T

W

l1 / E -1 / Eq

(6)

b

db = E ln IS - ln h + ln h - a Eb - E

ln IS =

af

Substituting (6) into (5) and rearranging, we obtain the following

site index function:

af

db = Ed ln h + ln h - a dE

a f af

a f af

Eb - E

}

(7)

b

Function (7) was derived from an site index anamorphic function;

however, adding the db component makes it also variable in shape

within the age and height interval of interest, so it can be considered

as a site index ana-polymorphic function. This function has some

desirable features, such as the fact that when E = Eb then ln(h) =

LM

N

Eb

ln(IS). There is a general weight 2E - E

b

OP

Q

in (7) which is the inverse

of the difference between Eb and its proportion with E. As shown, the

La Función 7 se derivó a partir de una función anamórfica de

índice de sitio, sin embargo, al incorporar el componente db, la hace

también variable en forma dentro del intervalo de interés de edades y

weight is undefined when the age is twice or more than the base age

(E³2Eb), which would be very rare in practice. The result of such a

weight is to change the function’s shape as E gets farther from Eb in

90

AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 35, NÚMERO 1, ENERO-FEBRERO 2001

alturas, por lo que puede considerarse como una función anapolimórfica de índice de sitio. Esta función tiene algunas características

deseables en su estructura, como el hecho de que cuando E = Eb, en-

both directions. Another feature of Model 7 is that the term

1 / Eb - 1 / E

af

n

af

is weighted by -Eln h + ln h - a Eb - E

s , this

tonces ln(h) = ln(IS). En (7) existe un ponderador general

value reflects the site index curve’s scale change within the interval of

LM E OP

N 2E - E Q que es el inverso de la diferencia entre E y su proporción

interest, being equal to zero when E=Eb.

con E. Como se puede apreciar, el ponderador queda indefinido cuan-

interval. However, the change in (db) could be considered in its discrete

do la edad es mayor o igual al doble de la edad base (E³2Eb), caso

form (Db). To illustrate this strategy, assume the same Function 1 for

que en la práctica sería muy raro. El efecto de tal ponderación es cam-

the height-age relationship. If the (h, E) and (IS, Eb ) pairs are two

biar la forma de la función conforme E se aleja de Eb en ambos senti-

points within the curve, and from (1) it is known that b = [ln(h)-a]E,

dos. Una característica más del Modelo 7 es que el término

1 / Eb - 1 / E está ponderado por -Eln h + ln h - a Eb - E ,

then Db can be defined as:

b

b

b

n

af

af

s

The site index model defined in (7) assumes that the shape

parameter b continuously changes (db) within the age and height

c a f h

valor que refleja el cambio en la escala de la curva de índice de sitio

c af h

Db = bEb - bE = ln IS - a Eb - ln h - a E

dentro del intervalo de interés, siendo nulo cuando E=Eb.

(8)

El modelo de índice de sitio definido en (7) supone que el

parámetro de forma b cambia continuamente (db) dentro del intervalo

de alturas y edades. Sin embargo, el cambio (db) también podría considerarse en forma discreta (Db). Para ilustrar esta estrategia supóngase

la misma Función 1 para la relación altura-edad. Si los pares (h, E) y

(IS, Eb ) son dos puntos dentro de la curva, y de (1) se sabe que b =

where bE is the value of b at age Eb (and height IS) and bE is the value

b

of b at age E (and height h). Substituting (8) into (5) and changing db

by Db, it is possible to obtain an ana-polymorphic function, under the

assumption of discrete changes in the shape parameter b, within the

interval of interest. The resulting function has the form:

[ln(h)-a]E, entonces Db se puede definir como:

c a f h

a f LM EE OP lnahf + a1 / E -1 / E f

N Q

cb - aE - lnahfE + aE h

ln IS =

c af h

Db = bEb - bE = ln IS - a Eb - ln h - a E

b

b

(8)

(9)

b

donde bE es el valor de b a la edad Eb (y altura IS) y bE es el valor de

b

b a la edad E (y altura h). Al sustituir (8) en (5) y cambiar db por Db,

es posible obtener una función ana-polimórfica, bajo la suposición de

cambios discretos en el parámetro de forma b, dentro del intervalo de

interés. La función resultante tiene la forma:

The procedure used to define an ana-polymorphic function can

be repeated to define a poly-anamorphic. This is a function that adds a

variation of the scale parameter (a) to a polymorphic function. The

a f LM EE OP lnahf + a1 / E -1 / E f

N Q

cb- aE - lnahfE + aE h

ln IS =

Functions 7 and 9 are similar and the main difference between

them is the weight.

reader can verify that for Model 1 and assuming a continus change in

the scale parameter (da), the poly-anamorphic curve that can be derived

b

b

(9)

has the following expression:

b

a f LMN EE -1OPQ LMNa+ Eb aE - E fOPQ +lnahfLMN2- EE OPQ

ln IS =

Las Funciones 7 y 9 son similares y la diferencia básica entre

b

2

b

b

(10)

ellas es el ponderador.

El procedimiento seguido para definir una función ana-polimórfica

se puede repetir para definir una poli-anamórfica, esto es, una en la

On the other hand, if the change is discrete (Da), then the

expression is:

que a partir de una función polimórfica se incorpore una variación del

a f LMN EE OPQ a - lnahf + ba1 / E -1 / E f + 2 lnahf

- a + ba1 / E - 1 / E f

parámetro de escala (a). El lector puede comprobar que para el Mode-

ln IS =

lo 1 y al suponer un cambio continuo en el parámetro de escala (da),

la curva poli-anamórfica que se puede derivar tiene la siguiente ex-

b

b

(11)

b

presión:

a f LMN EE -1OPQ LMNa+ Eb aE - E fOPQ +lnahfLMN2- EE OPQ

ln IS =

b

2

b

b

Using equation (4) it is possible to rearrange terms and rewrite

(10)

mientras que si el cambio es discreto Da adoptará la siguiente expresión:

(11) as:

a f

ln IS = LISA +

LM E -1OP a- lnahf + ba1 / E -1 / E fFG E IJ (12)

HEK

NE Q

b

b

b

TORRES-ROJO: CURVAS COMPUESTAS DE ÍNDICE DE SITIO EN INVESTIGACIÓN FORESTAL

a f LMN EE OPQ a- lnahf + ba1 / E -1 / E f + 2 lnahf

- a + ba1 / E - 1 / E f

ln IS =

b

b

(11)

b

Con la Ecuación 4 es posible reacomodar términos y reescribir

(11) como:

a f

ln IS = LISA +

LM E -1OP a- lnahf + ba1 / E -1 / E fFG E IJ (12)

HEK

NE Q

b

b

b

donde LISA representa el valor del logaritmo del índice de sitio

anamórfico (lado derecho de la Expresión 4). En (12) se observa que

la nueva expresión de IS considera el modelo anamórfico, más una

ponderación que incluye el cambio de escala (segundo término del

lado derecho) y un factor adicional que considera la forma de la curva,

propocional a la diferencia entre la edad base y la edad de referencia

(tercer término del lado derecho).

Resulta obvio que las expresiones ana-polimórficas y las polianamórficas siempre serán diferentes a menos que la relación alturaedad sea una relación directa (h=E), en la que el parámetro de escala

y de forma son iguales a la unidad; sin embargo, éste es un caso poco

atractivo porque la relación altura: edad no es lineal. Adicionalmente,

es claro que al existir siempre una diferencia entre ambas formas se

vuelve a la disyuntiva original: ¿Qué es mejor: iniciar con una función anamórfica o con una polimórfica? Teóricamente las expresiones

finales incorporan tanto la variación en escala como en forma; sin

embargo, como se mostrará posteriormente, existen diferencias en su

comportamiento.

COMPARACIÓN DE FUNCIONES

DE ÍNDICE DE SITIO

La base de datos para las variables altura y edad se integró con

información proveniente de análisis troncales. La elección del arbolado no incluyó solamente arbolado dominante o codominante en un

rodal, aunque fue requisito que el arbolado fuese de varias edades y

que creciera libre de competencia y sobre diferentes condiciones de

sitio. Así se asegura que la información refleje el crecimiento real en

altura en una amplia gama de edades, evitando el sesgo de usar sólo

arbolado maduro. La muestra consistió de 164 árboles de diferentes

especies clasificados en tres grupos (Cuadro 1). El muestreo fue selectivo y se efectuó a lo largo de la región denominada Guanacevi-Tecuan,

localizada al Noreste del Edo. de Durango. Los análisis troncales se

hicieron de acuerdo con la metodología definida por Kiessling (1978),

mientras que la estimación de alturas derivada de tales análisis se hizo

de acuerdo con el método ISSA (Fabbio et al., 1994).

Los datos se dividieron aleatoriamente en dos grupos. El primero

se integró con 127 árboles, cuya información se utilizó para los ajustes de modelos. El segundo (37 árboles) se utilizó para validar los

modelos de índice de sitio probados (Cuadro 1). Adicionalmente, las

especies se dividieron en tres grupos de acuerdo con sus tasas de crecimiento en la zona de estudio. El análisis se realizó para cada grupo

de especies.

91

where LISA represents the logarithmic value of the anamorphic index

site (right hand side in expression 4). Equation (12) shows that the

new IS expression considers the anamorphic model, plus a weight that

includes scale change (right hand side, second term) and an additional

factor considering the curve’s shape, proportional to the difference

between base age and reference age (right hand side, third term).

It becomes obvious that ana-polymorphic and poly-anamorphic

expressions will be always different, unless the height-age relationship

is a direct one (h = E), for which the shape and scale parameters equal

the unit; however, this is not an attractive case because the height-age

relation is not linear. Additionally, it becomes clear that since there is

always a difference between these two forms, we return to the original

question: Is it better to start with an anamorphic or with a polymorphic

function? Theoretically, the final expressions incorporate variations

in scale and shape; however, as will be shown later, there are differences

in its behaviour.

SITE INDEX FUNCTIONS COMPARISONS

The database for height and age variables was integrated with

information from stem analyses. The choice of trees did not only

include the dominant or co-dominant trees in a stand, even though it

was required that trees had different ages and were growing free of

competition and on different site conditions. In this way it is certain

that the information reflects real height growth in a wide range of

ages, avoiding bias derived of using only mature trees. The sample

was made out of 164 trees of different species arranged in 3 different

groups (Table 1). The sampling was selective and was obtained along

the Guanaceví-Tecuan region, located to the northeast of Durango State.

The stem analyses were made following the methodology defined by

Kiessling (1978), while the height estimates derived from such analyses

were made following the ISSA methodology (Fabbio et al., 1994).

Data were randomly divided in two groups. The first one was made

out of 127 trees, whose information was used for model fitting. The

Cuadro 1. Número de análisis troncales por especie.

Table 1. Number of stem analysis per specie.

Especie

Pinus arizonica

Engelm.

Pinus duranguensis

Martínez

Pinus ayacahuite

K Ehrenb. ex Schltdl.

Pinus leiophylla

Schltdl. et Cham.

Pinus lumholtzii

Robinson & Fern.

Pinus herrerai Martínez

Pinus engelmanii Carr.

Pinus teocote

Schltdl. et Cham.

Total

Grupo de

especies

Núm. de árboles analizados

Núm. de árboles usados en

la validación

1

44

9

1

17

4

2

39

8

3

14

3

3

3

3

10

16

10

3

4

3

3

14

3

164

37

92

AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 35, NÚMERO 1, ENERO-FEBRERO 2001

Dada la disponibilidad de análisis troncales, se decidió utilizar la

metodología de la diferencia algebraica (Clutter et al., 1983) para estimar las funciones de índice de sitio. A fin de ampliar la muestra y

mejorar la calidad de la información, se tomaron varias diferencias de

los análisis troncales, esto es, en lugar de tomar sólo las alturas de una

década para definir edad y altura, inicial y final respectivamente, se

tomaron alturas con diferencias de 20, 30, 40 y 50 años cuando fuese

posible. De esta forma la información se enriqueció y se aumentó de

1659 a un total de 5038 observaciones. Otra ventaja de esta estrategia

es que permite agregar información para intervalos de proyección grandes de índice de sitio, con lo que es posible detectar polimorfismos en

las trayectorias. Los ajustes se realizaron por mínimos cuadrados ordinarios (lineales o no lineales de acuerdo con el modelo), usando los

procedimientos REG y NLIN del sistema SAS (1996).

Los Modelos ana-polimórficos 7 y 9 y poli-anamórficos 10 y 11

se compararon contra los modelos anamórficos y polimórficos derivados del modelo de Schumacher (1939) y del modelo de Richards

(Richards, 1959). En años recientes, este último modelo se ha modificado para mejorar los ajustes (Ker y Bowling, 1991) y para definir

índices de sitio polimórficos (Payandeh y Wang, 1994). También se

ha usado para evaluar nuevos modelos de crecimiento en altura

(Newnham, 1988; Ker y Bowling, 1991; Goelz y Burk, 1992; Payandeh

y Wang, 1994; Meng et al., 1997) de gran eficiencia. Para completar

la comparación e incluir modelos más eficientes se usaron también las

formas de tres parámetros del modelo de Richards definidas por Goelz

y Burk (1992) y la de Payandeh y Wang (1994). A continuación se

muestran los modelos utilizados:

second group (37 trees) was used to validate the site index models

tested (Table 1). Additionally, the species were divided in three groups

according to their growth rates within the studied area. The analysis

was made for each group of species.

Given the availability of stem analyses, it was was decided to use

the algebraic difference methodology (Clutter et al., 1983) to estimate

the site index functions. In order to enlarge the sample, and to improve

the quality of information, several differences of the stem analyses

were used; that is, rather than just taking the height of a decade to

define age and height, initial and final respectively, heights with

differences of 20, 30, 40 and 50 years were taken when possible. In

this way information was enriched and the number of observations

rose from 1659 to 5038. Another advantage of this strategy is that

allows to add information to large site index projection intervals, which

enables to detect polymorphisms in the trajectories. Adjustments were

made by ordinary least squares (linear or non-linear according to the

model), using the REG and NLIN procedures of the SAS system (1996).

The ana-polymorphic models 7 and 9 and the poly-anamorphic

models 10 and 11 were compared to the anamorphic and polymorphic

derived from the Schumacher model (1939), and from the Richards

model (Richards, 1959). In recent years the later model has been

modified to improve the fits (Ker and Bowling, 1991) and to define

polymorphic site index curves (Payandeh and Wang, 1994). It has also

been used to evaluate new height growth models (Newnham, 1988;

Ker and Bowling, 1991; Goelz and Burk, 1992; Payandeh and Wang,

1994; Meng et al., 1997) of great efficiency. To complete the

comparison and in order to include more efficient models the three

parameter form from the Richards model defined by Goelz and Burk

(1992) and Payandeh and Wang (1994) were used. The models are

shown below:

Modelo anamórfico (Schumacher):

ma f

h2 = exp ln h1 + b 1 / Eb - 1 / E

r

Anamorphic model (Scumacher):

ma f

h2 = exp ln h1 + b 1 / Eb -1 / E

Modelo polimórfico (Schumacher):

Polymorphic model (Schumacher):

RS

T

af

E

Eb

h2 = exp a + ln h - a

UV

W

RS

T

af

E

Eb

h2 = exp a + ln h - a

Modelo anamórfico (Richards):

Anamorphic model (Richards):

h2 = h1

LM 1- e

MN 1- e

b 2 E2

b 2 E1

OP

PQ

b3

Modelo polimórfico (Richards):

d

h2 = b1 1- e bE2

LM F h I OP

MM GH b JK PP

N

Q

1

-1

donde b = E1 ln 1-

1

1

b3

h2 = h1

LM 1- e OP

MN 1- e PQ

b 2 E2

b3

b 2 E1

Polymorphic model (Richards):

i

b3

d

h2 = b1 1- e bE2

LM F h I OP

MM GH b JK PP

N

Q

1

where b = E1 1ln 1-

1

1

b3

i

b3

UV

W

r

TORRES-ROJO: CURVAS COMPUESTAS DE ÍNDICE DE SITIO EN INVESTIGACIÓN FORESTAL

Modelo polimórfico de Goelz y Burk (1992):

Goelz and Burk’s polymorphic model (1992):

L Fh I

O

1- expM- b G J E E P

MN H E K

PQ

h =h

L Fh I

O

1- expM- b G J E E P

MN H E K

PQ

b4

b2

1

1- exp - b1

1

2

1

b2

1

h2 = h1

b3

1

1

1

b

d

i

h2 = b1h1 2 1- e b 3E2

1

b2

b3

1

1

1

1

Payandeh and Wang’s polimorphic model (1994):

v

donde

b4

b3

2

1

1

1

1

Modelo polimórfico de Payandeh y Wang (1994):

LM F h I

O

E E P

G

J

MN H E K

PQ

L Fh I

O

1- expM- b G J E E P

E

MN H K

PQ

b2

b3

2

1

1

93

b

d

i

h2 = b1h1 2 1- e b 3E2

v

where

F h I

GH b h JK

ln

v=

d

1

b2

1 1

- b 3E1

ln 1- e

i

v=

En estos modelos h1 y h2 representan respectivamente la altura

inicial y final, mientras que E1 y E2 representan las edades inicial y

final.

Una vez ajustados los diferentes modelos se procedió a su validación. El análisis consistió en calcular valores de los estadísticos R²

tanto para toda la muestra como para varias diferencias de edad. Este

segundo análisis se realizó con el fin de identificar el efecto de la

diferencia de edad en la predicción de la altura. El estadístico R² se

calculó con la fórmula:

R2 = 1-

F h I

GH b h JK

ln

ådhi - h$i i

åchi - h h

2

2

donde hi = Altura real a la edad de proyección para la i-ésima observación; h$i = Altura predicha a la edad de proyección para la i-ésima

observación; y h = Altura real promedio.

RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓN

El Cuadro 2 muestra los resultados de los ajustes obtenidos para el primer grupo de especies, mientras que

los Cuadros 3 y 4 presentan los de los Grupos 2 y 3.

Obsérvese que en los tres cuadros las varianzas son

aproximadamente de la misma escala, pues los modelos

de escala y forma variable se ajustaron en su forma no

lineal usando como variable dependiente la altura y no el

logaritmo de esta variable, que es como lo muestran las

Ecuaciones 3, 5, 6 y 9. Adicionalmente es importante

hacer notar que el modelo denominado curva guía corresponde al Modelo 1 igualmente ajustado en su forma

d

1

b2

1 1

- b 3E1

ln 1- e

i

In these models h1 and h2 represent the initial and final height

respectively, while and represent initial and final age respectively.

Once all different models were fitted, a validation process was

carried out. The analysis consisted in calculating the values of the R2

statistics for the whole sample and for several age differences. The

purpose of this second analysis was to identify the effect of the age

difference on forecasting height. The R2 statistic was calculated

according to the formulae:

R2 = 1-

ådhi - h$i i

åchi - h h

2

2

where hi = Current height at projection age for the i-th observation;

h$i = Forecasted height at projection age for the i-th observation; h =

Average current height.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 2 shows the results of the fits obtained for the

first group of species, while tables 3 and 4 present the

results from groups 2 and 3.

Notice that in these three tables the variances are

approximately of the same scale, this is because the

variable shape and scale models were adjusted in their

non-linear form, using height rather than the variable’s

logarithm as dependent variable, as shown in equations

3, 5, 6 and 9. Additionally it is important to point out that

the model denominated guide curve corresponds to Model

1 also fitted in its non-linear form. The later model was

94

AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 35, NÚMERO 1, ENERO-FEBRERO 2001

Cuadro 2. Estadísticos de bondad de ajuste para diferentes formas de las curvas de índice de sitio para el Grupo 1.

Table 2. Goodness of fit statistics for different shapes of index site curves for Group 1.

Estimador de a

Modelo

Curva guía

Anamórfica (Schumacher)

Polimórfica (Shumacher)

Ana-polimórfica con cambio continuo

Ana-polimórfica con cambio discreto

Poli-anamórfica con cambio continuo

Poli-anamórfica con cambio discreto

Anamórfica (Richards)

Polimórfica (Richards)

Goelz y Burk (1992)

Payandeh y Wang (1994)

†

R²†

0.723

0.792

0.823

0.830

0.841

0.846

0.866

0.834

0.885

0.490

0.843

Valor

Estimador de b

Significancia

3.233

**

Estimador

Significancia

-45.182

**

**

-44.493

3.493

2.122

3.831

3.390

3.5383

b2 = -0.017

b1 = 27.010

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

-50.600

**

**

**

**

**

**

-37.817

-21.997

-59.037

b3 = 1.725

b3 = 2.009

Varianza

del

modelo

6.123

5.564

3.267

3.167

3.005

2.927

2.598

3.445

2.068

11.94

2.72

Para todos los modelos el estadístico R² corresponde al valor de R² ajustada.

Cuadro 3. Estadísticos de bondad de ajuste para diferentes formas de las curvas de índice de sitio para el Grupo 2.

Table 3. Goodness of fit statistics for different shapes of index site curves for Group 2.

Estimador de a

Modelo

Curva guía

Anamórfica (Schumacher)

Polimórfica (Shumacher)

Ana-polimórfica con cambio continuo

Ana-polimórfica con cambio discreto

Poli-anamórfica con cambio continuo

Poli-anamórfica con cambio discreto

Anamórfica (Richards)

Polimórfica (Richards)

Goelz y Burk (1992)

Payandeh y Wang (1994)

†

R²†

0.654

0.634

0.824

0.647

0.734

0.718

0.758

0.707

0.825

0.4486

0.848

Valor

Estimador de b

Significancia

3.080

**

Estimador

Significancia

-41.010

**

**

-38.981

3.400

2.040

3.559

3.242

3.422

b2 = -0.014

b1 = 20.960

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

-50.384

**

**

**

**

**

**

-37.614

-18.475

-49.717

b3 = 1.448

b3 = 2.531

Varianza

del

modelo

7.134

6.883

3.319

6.670

5.025

5.32

4.560

5.53

3.318

9.135

3.168

Para todos los modelos el estadístico R² corresponde al valor de R² ajustada.

Cuadro 4. Estadísticos de bondad de ajuste para diferentes formas de las curvas de índice de sitio para el Grupo 3.

Table 4. Goodness of fit statistics for different shapes of index site curves for Group 3.

Estimador de a

Modelo

Curva guía

Anamórfica (Schumacher)

Polimórfica (Shumacher)

Ana-polimórfica con cambio continuo

Ana-polimórfica con cambio discreto

Poli-anamórfica con cambio continuo

Poli-anamórfica con cambio discreto

Anamórfica (Richards)

Polimórfica (Richards)

Goelz y Burk (1992)

Payandeh y Wang (1994)

†

R²†

0.589

0.650

0.834

0.719

0.761

0.793

0.750

0.673

0.806

0.643

0.712

Valor

3.083

Estimador de b

Significancia

**

Estimador

-40.685

-40.317

3.454

2.034

3.415

3.260

3.439

b2 = -0.023

b1 = 23.300

Para todos los modelos el estadístico R² corresponde al valor de R² ajustada.

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

-54.816

-44.279

-17.983

-48.853

b3 = 1.824

b3 = 2.409

Significancia

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

**

Varianza

del

modelo

8.192

7.427

3.562

5.973

5.090

5.465

5.323

6.973

4.123

8.311

5.870

TORRES-ROJO: CURVAS COMPUESTAS DE ÍNDICE DE SITIO EN INVESTIGACIÓN FORESTAL

adjusted with the purpose of comparing the a and b

estimated values obtained from different forms of site

index.

The use of several age differences within each group

makes the curves’ trajectories show more clearly the shape

differences caused by site variations. Doubtless, this is

amplified by the use of various species in each group,

since for the same initial height-age pair (base age) several

projection values are given (projection age).

For the fist group of species, the composed anapolymorphic and poly-anamorphic models yield better

fits than the simple model (anamorphic or polymorphic)

and even than the improved models of Goelz and Burk

(1992) or Payandeh and Wang (1994), which include more

parameters. The best model for this group was the

polymorphic form derived from Richards. It also can be

noticed that for this group of species, and even for the

other groups, the poly-anamorphic forms had better

performance than the ana-polymorphic.

Results obtained for Group 2 and Group 3 are similar

to those obtained for Group 1; even though for these

groups the polymorphic form derived from the

Schumacher model had better adjustment than the

composed forms and even than the polymorphic form

derived from the Richards’ model.

Stands out the fact that the estimates of composed

models were similar to the ones obtained with the guide

curve, this means that these are estimates that resemble

the model’s original form, which relates height-age.

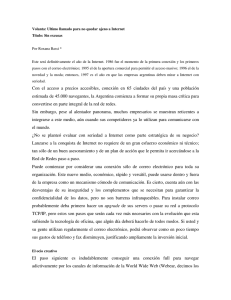

Figure 1 shows the form that two composed models adopts

for the first group of species using 80 years as base age.

Here we can notice an important difference between the

ana-polymorphic and the poly-anamorphic curves. The

first maintain the trajectory of a growth function because

of their anamorphic base, while the shape change happens

25

Polimórfica

Ana-polimórfica

Poli-anamórfica

20

Altura (m)

no lineal. Este último modelo se ajustó a fin de comparar

los valores de los estimadores de a y b obtenidos con

diferentes formas de índice de sitio.

El uso de varias diferencias de edad en cada grupo

hace que las tendencias de las curvas muestren más claramente las diferencias en forma ocasionadas por variaciones en sitio. Ello sin duda se ve amplificado por el uso

de varias especies en cada grupo, dado que para una misma dupla de altura-edad iniciales (edad base) se proporcionan diferentes valores de proyección (edad de proyección).

Para el primer grupo de especies, los modelos compuestos ana-polimórfico y poli-anamórfico proporcionaron mejor ajuste que el modelo simple (anamórfico o

polimórfico) e incluso que los modelos mejorados como

el de Goelz y Burk (1992) o el de Payandeh y Wang

(1994), mismos que tienen mayor cantidad de parámetros. Para este grupo el mejor modelo fue la forma

polimórfica derivada de Richards. Asimismo, se puede

observar que para este grupo de especies, e incluso para

los demás grupos, las formas poli-anamórficas tuvieron

mejor desempeño que las ana-polimórficas.

Los resultados, tanto para el Grupo 2 como para el

Grupo 3, fueron similares a los obtenidos para el Grupo

1; aunque para estos grupos la forma polimórfica derivada del modelo de Schumacher resultó con mejor ajuste

que las formas compuestas e incluso mejor que la forma

polimórfica derivada del modelo de Richards.

Destaca que los estimadores de los modelos compuestos fueron similares a los obtenidos con la curva guía,

esto es, son estimadores que se asemejan a la forma original del modelo que relaciona altura-edad. La Figura 1

muestra la forma que adoptan dos modelos compuestos

para el primer grupo de especies usando como edad base

80 años. Aquí se puede apreciar una diferencia notable

entre las curvas ana-polimórficas y las poli-anamórficas.

Las primeras conservan la tendencia de una función de

crecimiento dado que su base es anamórfica, mientras

que el cambio en forma es en el largo plazo (intervalos

grandes). Por el contrario, las curvas poli-anamórficas

tienen un cambio en forma en el corto plazo (intervalos

pequeños) y adoptan la forma genérica de la función; en

este caso, una función no decreciente (modelo de

Shumacher).

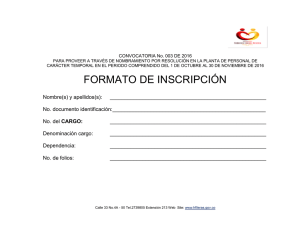

La Figura 2 muestra la tendencia de las curvas polianamórficas (discretas) para tres índices de sitio. Como

se puede apreciar, son curvas que muestran la tendencia

general del modelo de Schumacher, sin embargo dan la

impresión de tener un comportamiento discontinuo (mucha variación entre una y otra edad) al considerar la variación de forma y escala a la vez.

El desempeño de las diferentes formas de curvas en

la predicción de índices de sitio, se midió con una prueba

de validación utilizando la base de datos previamente

95

15

10

5

0

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

Edad (años)

Figura 1. Comparación entre curvas compuestas y una curva

polimórfica.

Figure 1. Comparison between composite curves and a

polimorphic curve.

AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 35, NÚMERO 1, ENERO-FEBRERO 2001

35

IS = 15

IS = 20

IS = 25

30

Altura (m)

25

20

15

10

5

0

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

Edad (años)

Figura 2. Comportamiento de tres curvas poli-anamórficas para

el Grupo 1.

Figure 2. Behavior of three poly-anamorphic curves for group 1.

separada. El Cuadro 5 muestra los resultados indicando

sólo el estadístico R² y para el primer grupo de especies.

En este cuadro la primera columna de cifras ha sido denominada promedio para indicar que la prueba de validación se realizó con toda la muestra, esto es, con todas

las diferencias de edad. Los encabezados 10, 30 y 50 indican que la prueba sólo se efectuó para aquellos pares

de datos (altura-edad) con 10, 30 y 50 años de diferencia.

Como se puede apreciar, los modelos compuestos son

bastante competitivos en términos de ajuste con respecto

a los modelos tradicionales anamórficos o polimórficos

especialmente cuando éstos tienen el mismo número de

parámetros. En la prueba es notable el buen desempeño

que tienen los modelos mejorados de Goelz y Burk (1992)

y el de Payandeh y Wang (1994), probablemente debido

al mayor número de parámetros. Es importante notar que

cuando las diferencias de edad son pequeñas, el modelo

poli-anamórfico es muy eficiente, probablemente debido

a que como se señaló, identifica las diferencias de forma

en altura en intervalos pequeños de edad. Una observación detenida del modelo ana-polimórfico muestra que

este modelo mejora con respecto al poli-anamórfico en

la medida que la diferencia de edad aumenta, lo cual corrobora lo que ya se había señalado.

Payandeh y Wang (1994) mostraron que es importante aplicar pruebas de validación de los modelos de índice de sitio considerando datos con varias diferencias

de edad. El Cuadro 5 muestra que no sólo es necesario

incluir varias diferencias de edad, sino que también es

importante evaluar los modelos por rangos de tales diferencias. De lo contrario se puede llegar a seleccionar un

modelo poco eficiente. Por ejemplo, si la prueba de validación no hubiese incluido varias diferencias de edad, la

in the long run (large size intervals). On the contrary, on

the poly-anamorphic curves the shape change happens

in the short run (small size intervals) and acquire the

function’s generic form, in this case, a non-decreasing

function (Schumacher Model).

Figure 2 shows the tendency of poly-anamorphic

curves (discrete) for three site index. As can be seen, these

are curves that show the general trajectory of the

Schumacher model, however they seem to have a

discontinuous behavior (large variations between ages),

considering the scale and shape variation at the same time.

The performance of different curve forms to forecast

site index, was measured with a validation test using the

previously selected database. Table 5 shows first

numerical column the results indicating only the R2

statistic and for the first group of species. In this Table

the first numerical column has been denominated average

to indicate that the validation test was made with the whole

sample, that is, with all the age differences. The headings

10, 30 and 50 indicate that the test was made only for the

pairs of data (height-age) with 10, 30 and 50 years of

difference.

As can be noticed, the composed models are fairly

competitive in terms of fit compared to the traditional

anamorphic and polymorphic models, particularly when

these have the same number of parameters. In the test is

remarkable the good performance attained by the improved

models of Goelz and Burk (1992) and of Payandeh and

Wang (1994), probably due to the larger number of

parameters. It is important to notice that when the age

differences are small, the poly-anamorphic model is very

efficient, probably, as was previously indicated, because it

identifies height form differences in small age intervals.

Cuadro 5. Valores de R² para la prueba de validación de proyecciones de altura para el Grupo 1.

2

Table

25 5. R values in the validation test for height projections in

GroupPolimórfica

1.

Ana-polimórfica

Poli-anamórfica Diferencia promedio en edades

20

de proyección (años)

Modelo

15

Promedio

10

30

50

Altura (m)

96

Anamórfica (Schumacher)

10

Polimórfica

(Shumacher)

Ana-polimórfica con

cambio

continuo

5

Ana-polimórfica con

cambio discreto

Poli-anamórfica

con

0

cambio

0 continuo

20

40

Poli-anamórfica con

cambio discreto

Anamórfica (Richards)

Polimórfica (Richards)

Goelz y Burk (1992)

Payandeh y Wang (1994)

0.537

0.643

0.853

0.880

0.238

0.522

0.084

0.359

0.552

0.857

0.360

0.218

0.590

0.859

0.409

0.362

0.613

60

800.876100 0.235

120

Edad

0.646(años)0.889

0.537

0.853

0.626

0.873

0.506

0.825

0.694

0.889

0.231

0.290

0.476

0.400

0.518

0.134

140

0.155

0.071

0.310

0.377

0.402

TORRES-ROJO: CURVAS COMPUESTAS DE ÍNDICE DE SITIO EN INVESTIGACIÓN FORESTAL

forma poli-anamórfica hubiese sido una buena selección;

sin embargo, considerando diferencias más amplias de

edad, es evidente que tal selección resulta inapropiada.

La información del Cuadro 5 también orienta acerca

de la conveniencia de usar cada tipo de curvas. Se observa que en la medida en que la diferencia de edad es más

pequeña las curvas poli-anamórficas son consistentemente

más eficientes. Por el contrario, a medida que tal diferencia aumenta, las funciones ana-polimórficas son más eficientes. Esto sólo indica que cuando el intervalo de predicción de índices de sitio es pequeño son más importantes los cambios en forma que la tendencia general de la

curva y viceversa, cuando el intervalo es grande, resulta

de mayor importancia la tendencia general de la curva.

Este resultado, no sólo es lógico, sino que ha sido usado

empíricamente. Es común encontrar en la bibliografía

recomendaciones sobre el uso de formas polimórficas para

evaluar índices de sitio en plantaciones (Bailey y Clutter,

1974; Winston y Demaerschalk, 1981; Payandeh y Wang,

1994) y el uso de formas anamórficas para evaluar poblaciones naturales (Hann, 1995).

CONCLUSIONES

La integración del gradiente instantáneo, o cambio

diferencial del parámetro que permanece constante al derivar una forma anamófica o polimórfica de índice de sitio, permite derivar una función ana-polimórfica o polianamórfica dependiendo del gradiente o cambio que se

incluya. Estas funciones son eficientes para estimar índices de sitio, comparadas con las que tienen el mismo

número de parámetros. La prueba empírica mostró que

las diferencias en R² no son superiores a 10% del mejor

ajuste. Las formas poli-anamórficas predicen eficientemente índices de sitio cuando las diferencias de edad son

pequeñas (menos de 20 años), mientras que las formas

ana-polimórficas son eficientes sólo si la diferencia de

edad es mayor. Ambas formas compuestas permiten modificar en escala y forma la trayectoria típica de la función, logrando más detalle en la evaluación. La selección

de modelos de índice de sitio debe basarse en una prueba

de validación. Es importante que en esta prueba se analicen varias diferencias de edad a fin de evaluar el desempeño de los modelos con diferentes intervalos de proyección.

LITERATURA CITADA

Bailey, R. L., and J. L. Clutter. 1974. Base-age invariant polymorphic

site curves. For. Sci. 20: 155-159.

Clutter, J. L., J. C. Fortson, J. C. Piennar, L. V. Brister, and R. L. Bailey.

1983. Timber Management: A Quantitative Approach. Wiley. New

York. 333 p.

Fabbio, G., M. Frattegiani, and M. CH. Manetti. 1994. Height

estimation in stem analysis using second differences. For. Sci. 40:

329-340.

97

A deeper observation of the ana-polymorphic model

shows that as age differences get larger this model

improves compared with the poly-anamorphic model.

This corroborates what had been previously pointed out.

Payandeh and Wang (1994) showed that it is important

to apply validation tests of site index models using data

with several age differences. Table 5 shows that is not

only necessary to include several age differences, but is

also important to evaluate models for ranges of such

differences. Otherwise, a model with less efficiency could

be chosen. For example, if the validation test would not

had included several age differences, the ana-polymorphic

form would have been a good choice, however, it is clear

that if wider age differences are included, it is an

inappropriate choice.

Information on table 5 gives directions on how to use

each type of curve. It shows that as age differences get

smaller, poly-anamorphic curves are consistently more

efficient. On the other hand, as age differences get bigger

the ana-polymorphic functions are more efficient. This

only shows that when the forecast interval of site index is

small, the form changes are more important than the

general tendency of the curve and, viceversa, when the

interval is large, the general trajectory of the curve is more

important. This result is not only logical, but it has also

been used empirically. It is common to find bibliographic

recomendation about the use of polymorphic forms to

evaluate site index plantations (Bailey and Clutter, 1974;

Winston and Demaerschalk, 1981; Payandeh and Wang,

1994) and the use of anamorphic forms to evaluate natural

populations (Hann, 1995).

CONCLUSIONS

The integration of the instant gradient, or differential

change in the parameter that remains constant when

deriving a site index anamorphic or polymorphic form,

allows to derive an ana-polymorphic or a polyanamorphic form depending on the gradient or change to

be included. These functions are efficient to estimate site

index, compared to others that have the same number of

parameters. The empirical test showed that the

R2 differences are not larger than a 10% from the best fit.

Poly-anamorphic forms efficiently forecast site index

when age differences are small (less than 20 years), while

ana-polymorphic forms are efficient only if the difference

is larger. Both composed forms allow modifying in shape

and scale the typical function trajectory, attaining greater

detail in the evaluation process. Selection of site index

models should be based on a validation test. For this test

it is important to analyze several age differences in order

to evaluate the performance of models with different

projection intervals.

—End of the English version—

pppvPPP

98

AGROCIENCIA VOLUMEN 35, NÚMERO 1, ENERO-FEBRERO 2001

Goelz, J. C. G., and T. E. Burk. 1992. Development of a well-behaved

site index equation: Jack pine in north central Ontario. Can. J.

For. Res. 22: 776-784.

Hahn, T., and W. H. Carmean. 1982. Lake states site index curves

formulated. USDA. Forest Service. Gen. Tech. Rep. NC-88. 5 p.

Hann, D. W. 1995. A key to the literature presenting site-index and

dominant-height-growth curves and equations for species in the

Pacific Northwest and California. For. Res. Lab. Oregon State Univ.

Corvallis, Oregon. Research Contribution. No. 7. 26 p.

Ker, M. F., and C. Bowling. 1991. Polimorphic site index equations

for four New Brunswick softwood species. Can J. For. Res. 21:

728-732.

Kiessling, D., F. J. 1978. Análisis troncales, ejecución, aplicación actual y perspectivas. In: La Investigación Forestal en las Unidades

Forestales y Organismos Descentralizados. Primera Reunión. Pub.

Esp. No. 15. INIF. México. pp: 9-54.

Meng, Fan-Rui, Ch. H. Meng, S. Tang, and P. A. Arp. 1997. A new

height growth model for dominant and codominant trees. For. Sci.

43: 348-354.

Newnham, R. M. 1988. A modification of the Ek-Payandeh nonlinear

regression model for site index curves. Can J. For. Res. 18: 115120.

Payandeh, B. 1977. Metric site index formulae for major Canadian

timber species. Bi-monthly Res. Notes 33:37-39.

Payandeh, B., and Y. Wang. 1994. Relative accuracy of a new baseage invariant site index model. For. Sci. 40:341-343.

Richards, F. J. 1959. A flexible growth function for empirical use. J.

Exp. Bot. 10: 290-300.

SAS. Institute. 1996. Version 6.12. SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC. USA.

Schumacher, F. X. 1939. A new growth curve and its application to

timber yield studies. J. For. 37: 819-820.

Stansfield, W. F., J. P. McTagle, and R. Lacapa. 1991. Dominant height

and site index equations for ponderosa pine in east central Arizona.

Can. J. For. Res. 21: 606-611.

Winston, J. K., and J. P. Demaerschalk. 1981. Height-age functions

for young stands of exotic timber species in Kenia. A comparison

of linear and nonlinear models. Forestry 13: 120-134.