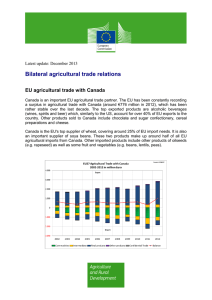

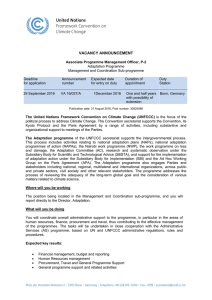

Agriculture and Natural Resources Building Resilience and

Anuncio