metaphors in Basque - Universidad de Zaragoza

Anuncio

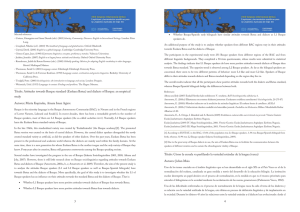

(Under review) In A. Idström, E. Piirainen, K. Willson (eds.) Endangered metaphors. Ámsterdam/Philadephia: John Benjamins. The importance of unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language: The case of Basque* Iraide Ibarretxe-Antuñano Universidad de Zaragoza iraide@unizar.es Gure hitzak, Esan berriz esan Ez daitezela ahaztu Ez daitezela gal, Elur gainean Txori hanka arinek Utzitako arrasto sail ederra bezalaxe Mikel Laboa (Basque singer, Gure Hitzak)1 This paper studies some (external and internal) body-part related conceptual metaphors in Basque, a language isolate spoken on the Western Pyrenees, and discusses the importance and relevance of such a study for endangered languages in general and Basque in particular. The goal of this paper is twofold: (1) to show that culture plays a fundamental role in the analysis of conceptual metaphors, since all metaphors are not ‘universal’ despite the claim that they share a common embodied grounding, and (2) to prove that conceptual metaphor is a critical tool in the study of endangered languages, Basque in this case, because it unveils certain conceptualisations that are deeply entrenched in the language and that are sometimes overshadowed by a globalised and enthnocentric viewpoint. Keywords: Basque, body-parts, metaphor, culture * Research supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation, Grant FFI2010-14903. I would like to thank the editors for their invitation to participate in this volume and for their patience. 1 Our words, let’s say it again and again, they cannot be forgotten, they cannot be lost like the graceful traces that birds’ quick feet leave on the snow. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 2 This paper studies some (external and internal) body-part related conceptual metaphors in Basque, a language isolate spoken on the Western Pyrenees, and discusses the importance and relevance of such a study for endangered languages in general and Basque in particular. The goal of this paper is twofold: (1) to show that culture plays a fundamental role in the analysis of conceptual metaphors, since all metaphors are not ‘universal’ despite the claim that they share a common embodied grounding, and (2) to prove that conceptual metaphor is a critical tool in the study of endangered languages, Basque in this case, because it unveils certain conceptualisations that are deeply entrenched in the language and that are sometimes overshadowed by a globalised and enthnocentric viewpoint. The first section offers a brief overview of the basic tenets in conceptual metaphor theory, especially those related to the concepts of embodiment, universality, and culture. Section two describes some of the metaphorical conceptualisations underlying body parts in Basque such as buru ‘head’, begi ‘eye’, oin ‘foot’, gibel ‘liver’, bihotz ‘heart’ as well as culture specific concepts such as gogo. The aim here is to highlight those cases that seem to be particular to Basque and to pinpoint those that are also found in some other languages. The final section aims at shedding some light on how exploring the conceptual metaphors underlying some linguistic expressions may help describe the lexico-semantic system of a given language--versus more traditional methods, such as listing the words in semantic fields. It is therefore argued that conceptual metaphor should be a ‘must’ in the study of semantics and in language description and documentation. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 3 1. Conceptual metaphor in language, thought and culture Conceptual metaphor in Cognitive Linguistics is traditionally defined as a mapping between two conceptual domains, where properties from one domain (the source) are transferred onto another domain (the target). Classical and well-known examples of a metaphorical mapping would be UNDERSTANDING/KNOWING IS SEEING the cases of TIME IS SPACE and as instantiated in expressions such as to leave the past behind and to see what a person means, respectively. In the former, the source domain SPACE offers certain characteristics that are transferred or mapped onto the target domain, TIME; more concretely, this is an example of the subcase ego- moving metaphor, here past time is understood as a physical that we pass by and therefore, leave behind us. In the latter, the target domain UNDERSTANDING/KNOWING selects characteristics from the domain of VISUAL PERCEPTION. Here, properties of the visual perceptual experience and its immediate result into quick, direct and trustworthy information may explain why this sense is mapped onto the domain of cognition. Consequently, as Lakoff and Johnson (1980: 5) point out in their seminal book Metaphors We Live By, one of the main functions of conceptual metaphor is that it helps us “understanding and experiencing one kind of thing in terms of another”. The conceptual associations between source and target have been often considered universal since they are said to be grounded on an experiential bodily basis shared by all human beings, and therefore, these mappings are also understood as motivated and embodied. In fact, universality, motivation, and embodiment2 are three key notions in 2 Embodiment in Cognitive Linguistics is interpreted in several ways (Geeraerts and Grondelaers 1995, Rohrer 2001). This paper follows Johnson’s (1987) definition of embodiment, see below. For more information about the different interpretations of embodiment in the literature, see Chrisley and Ziemke 2002, Violi 2004, 2008, Wilson 2002, Ziemke 2003, inter alia. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 4 this model; key concepts that, as discussed below, unite in themselves the ‘good’ and the ‘bad’ sides of the conceptual metaphor theory. On the one hand, one of the good points is that this view of metaphor as a largely automatic and motivated correspondence between experiential domains has been paramount to the field of semantics, more concretely, to the study of polysemy (see Croft and Cruse 2004: ch. 5, Evans and Green 2006: ch. 10, Geeraerts and Cuyckens 2007: ch. 6, Nerlich et al. 2003 for a general overview). A linguistic unit is generally said to be polysemous when it exhibits several different meanings. However, these semantic extensions are not whimsical or chosen at random; they are motivated by our experience and understanding of the world, and structured by means of metaphor (as well as other conceptual mechanisms such as metonymy). On the other hand, one of the main problems of conceptual metaphor theory is that a loose interpretation of the concept of embodiment3 has led some authors to ‘forget’ about the role that culture plays in the choice and interpretation of conceptual domains and the mappings within. Consequently, claims about the presumptive universality of some conceptual metaphors are widespread in the literature. A case in point is the metaphor UNDERSTANDING/KNOWING IS SEEING. Authors such as Lakoff and Johnson (1980, 1999) and Sweetser (1990) have argued in favour of the universal character of this metaphor, but research in non-Western cultures (e.g. Australian aborigines, Evans and Wilkins 2000) has quite strongly demonstrated that this metaphor is far from universal; the choice of source domain depends on culture, and it 3 Another criticism to the use of embodiment as the main explanation for conceptual mappings is that many of these studies are based on linguistic data resulting into a ‘circularity of reasoning’. As Valenzuela (2009: 240) explains: “A common methodology in metaphor theory has been to group together a given number of linguistic expressions, which are found to share certain common characteristics, and then use these expressions to propose a given conceptual metaphor; this conceptual metaphor is in turn used to explain why there is such as numerous group of these linguistic expressions”. Psycholinguistic studies are now successfully avoiding this circularity of reasoning (see Santiago, Román and Oullet in press, and Valenzuela 2009, for a review). Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language is by no means restricted to vision, but open to other perceptual modalities such as hearing, touch, and even smell (see Ibarretxe-Antuñano 2008a for a review). This does not mean that conceptual metaphors are then necessarily different in every single language. In fact, this is another good point in this theory: the ability to highlight shared conceptualisations of the world. Languages might have different linguistic means to codify these metaphors (what is known as ‘the metaphorical expression’), but the underlying mappings between different domains of experience are the same. In the case of vision metaphors, cross-linguistic studies have shown that the link between vision and intellect is indeed very pervasive not only in languages such as English (Alm-Arvius 1993, Baker 1999, Danesi 1990), but also in other IndoEuropean and non-Indo-European languages (Ibarretxe-Antuñano 1999, 2002a, Sweetser 1990, Viberg 2008). Since all of us have the same physiological and psychological apparatus for visual perception, it is only natural to argue that all human beings perceive and experience the sense of vision in the same way. This is why commonalities in embodied experience are related to similarities in sense perception conceptual metaphors across languages. Vision arguably plays a salient role in our conceptualisation of the intellect, but this saliency is neither shared by all cultures nor present in older stages in the IndoEuropean culture (Ong 1990, Tyler 1984). As a consequence, the motivation and grounding of a conceptual metaphor cannot be solely explained by means of a common body-basis, it has to be validated by the culture sieve in order to be understood correctly. According to Caballero and Ibarretxe-Antuñano (in press), this culture sieve plays “an instrumental role in the way our physical, sensory-motor grounding universal experiences pass through the complex and socially acquired 5 Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language particular beliefs, knowledge and worldwiew(s) intrinsic to belonging to one or several communities—i.e. C/cultures”. In fact, the cultural component in the notion of embodiment is not new; if we revise Johnson’s original definition for embodiment, he says: […] meaning and value are grounded in the nature of our bodies and brains, as they develop through ongoing interactions with various environments that have physical, social, and cultural dimensions. The nature of our embodied experience motivates and constrains how things are meaningful to us. (Johnson 1997: 154) In his definition, both the physical configuration and the socio-cultural background are central to the notion of embodiment. However, it is not until recently, that the relationship between culture and conceptual metaphors has started to receive the attention it deserves (see Dobrovol’skij and Piirainen 2005, Kövecses 2005, Sharifian 2003, Sharifian and Palmer 2007, Sharifian et al. 2008, Yu 2009, inter alia).4 This paper is yet another contribution to the role of metaphor in culture and to the role of culture in metaphor. It addresses this issue on the basis of Basque body-part data. Basque is a minority language spoken on both sides of the Western Pyrenees in three regions: Euskadi and Navarre in Spain and the Département des Pyrénées Atlantiques in France. Basque is a language isolate with extreme dialectal variation and typologically characterised by (1) its relatively simple phonology, (2) its 4 This does not mean that before these recent dates there was no interest in culture in cognitive linguistics; since the seminal work of Holland and Quinn (1987) on cultural models, culture was part of the research in this model. The main problem was, nevertheless, that many metaphor studies did not actually discuss the role that this culture sieve play in the grounding and conceptualization of the bodily-based metaphors they proposed; they took for granted the cultural component and assumed that many of these metaphors were just universal. 6 Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language agglutinating, suffixing, and mainly ergative morphology, (3) its accusative syntax with basic SOV word order, dependent-marking, and extended pro-drop, and (4) its rich lexicon for spatial nouns and ideophones, among other features (see Hualde and Ortiz de Urbina 2003, de Rijk 2008, Trask 1997 for an overview). The number of speakers is estimated around 1.000.000. The UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger (Moseley 2010) classifies Basque as vulnerable, i.e., but it notes that it is severely endangered on the French side with less than 80.000 speakers. 2. Body parts in Basque Body parts are rich polysemous words in every language; they develop metaphorical and metonymical semantic extensions of all sorts. Some of these extensions seem to be cross-linguistic. For example, body parts are very frequently the source of spatial terms (Heine 1989, Kahr 1975, Meillet 1912). Svorou (1993: 70-73), based on data from 55 languages, presents the following cross-linguistic mappings between spatial terms and body parts: (1) Front-region terms Æ Eye, face, forehead, mouth, head, breast, chest Back-region terms Æ Back, buttocks, anus, loins Top-region terms Æ Head, back Bottom-region terms Æ Side-region terms Æ Edge-location terms Æ Buttocks, hips Flank, ribs, abdomen, heart, ear Mouth, forehead 7 Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language Interior terms Æ Medial-region terms Æ Heart, stomach, blood, mouth, neck Chest, waist Emotional and mental activities are also related to body-part terminology in several languages. According to Sharifian, Dirven, Yu, and Niemeier (2008: 6), three are the main body regions that are considered the locus of the mind: the abdomen region, the heart region and the head (brain) region. These authors argue that ‘abdominocentrism’ is characteristic of Southern Asian and Polynesian cultures. For example, the liver in Indonesian and Malay, and the belly in the Australian language Kuuk Thaayorre are both related to emotions. ‘Cardiocentrism’ is the predominant approach in China, Japan, and Korea, whereas ‘cerebrocentrism’ is found in Greek-based West Asian, European and North African cultures, where there is a separation between intellect, which is located in the head (brain), and emotion, which is found in the heart. As we can see from these examples, body-parts, as a source domain, give rise to the same target domains, namely, space, emotions, and intellect. However, the internal mappings within these general domains are not necessarily the same, they vary across cultures. In what follows, some of the main metaphorical extensions in these abovementioned domains underlying internal and external body-parts in Basque are described. For this purpose, the body-parts buru ‘head’, begi ‘eye’, oin ‘foot’, gibel ‘liver’, bihotz ‘heart’ and the culture specific concept gogo are selected. These items have been chosen for two main reasons: (1) most of them are typical body-parts, frequently found in polysemy studies, therefore, one can contrast the results in Basque with other languages, (2) they offer a wide array of meanings,5 some will be common 5 In this paper, only a few meanings are picked up from the wide range of semantic extensions these words show. All data are drawn from several previous polysemy analyses on these words, which in turn are collected from different Basque corpora (www.EuskaraCorpusa.net) and several dictionaries. The interested reader may consult 8 Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 9 in other languages, whereas some other will either be different or be based on a different conceptual grounding. Therefore, stemming from these data, I will show not only that metaphor is culturally constrained, but also that metaphor is a very useful tool to uncover cultural information. 2.1. Space and External body-parts: buru ‘head’, begi ‘eye’, and oin ‘foot’ As shown in (1) above, the head is frequently associated with space, more concretely with the front and top regions. These two possible associations are also found in Basque. Buru can metonymically stand for the front part of the head as in expressions such as buru-z go-ra (head-INST high-all) ‘upside up’ and buru-z buru (head-INST head) ‘face to face’ and it can also represent the top part in a sentence like (2): (2) Mendiburu-ra igo ginen mountain.head-ALL ascend.PFV AUX ‘We climbed to the top of the mountain’ However, this interpretation—that buru means ‘front’ and ‘top’—is quite simplistic and hides the complexity underneath these conceptual mappings. Let us uncover some of these nuances. The semantic extension of a body-part like buru ‘head’ into ‘top part’ is only natural if we apply an anthropomorphic model that takes the human body as the basis for the spatial configuration. Human heads are at the top of our bodies, vertically oriented. This is what happens in example (2). Mountains do not have heads, but if one applies the following references for a whole detailed description: Ibarretxe-Antuñano 2002b, 2008b, in prep., and Ibarretxe-Antuñano and Garai 2004. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 10 the anthropomorphic orientation, the top part of the mountain is metaphorically understood as the head of the mountain. If fact, this top orientation is also the origin of very common orientational conceptual metaphors such STATUS IS UP, IMPORTANT IS UP, CONTROL IS UP, HIGH that can be illustrated in English with the word head in an example such as the head of the department. However, spatial orientation in body-parts, and in buru in particular, is not so simple. First of all, the spatial interpretation of the head can be also grounded on a zoomorphic orientation; therefore, the head is not the top part but one of the ends on a horizontal axis. A typical case of this zoomorphic orientation is the English expression a head-on collision between two freight trains. Here, the head represents one of the ends of the train, usually the front part, where the machine and the engineer travel. This zoomorphic basis is also present in Basque expressions such as ez bururik ez buztan-ik (no head-PART no tail-PART) ‘incomprehensible’. However, as I have argued before (Ibarretxe-Antuñano 2002b), there are expressions in Basque where it is difficult to decide whether the head refers to the top, the front or the back. In most cases, this specific vertical or horizontal orientation does not depend on the head, but on the co-occurring elements. If the word buru goes with mendi ‘mountain’ as in (2), its interpretation is ‘top’, if it co-occurs with hitz ‘word’, it means ‘beginning’, and if it appears with aste ‘week’ or hil ‘month’6 its meaning is ‘end’. In other words, buru seems to lexicalise only the meaning ‘extreme, end’, and it is the neighbouring words and contexts that allow buru to have more fine-grained interpretations.7 In fact, there are expressions in Basque such as buru-z buru (headINST 6 head) ‘from head to tail, from head to toe’ and buru bate-tik beste-ra (head one- Buruil (lit. head+month) means ‘September’ in some Eastern dialects. The reason why September is called ‘the final month’ seems to be cultural too. It is the last month of the harvesting season (Mitxelena 1997-2005: 814). 7 This is what I have called elsewhere “compositional polysemy”, i.e. the different semantic extensions of a given lexeme are obtained through the interaction of the semantic content of both the lexical item itself and its cooccurring elements in different degrees of interaction. (see Ibarretxe-Antuñano 1999). Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language ABL 11 other-ALL) ‘from one end to the other’, where one cannot tell but that it is just an extreme. What is more, there are cases like the expression buru buru-ko (head headADN) that have different diatopic meanings: ‘first’ for Northern dialects (Labourdin, Low Navarrese and Zuberoan) and ‘final’ for the rest. Apart from the ‘extreme’ spatial meaning, Basque buru develops another one; in some contexts, buru also means ‘centre’ as illustrated in (3). (3) Azaburu (cabbage.head) ‘heart of the cabbage’ Bideburu (road.head) ‘crossroads’ Kipulaburu (onion.head) ‘the heart of the onion’ Artaburu (corn.head) ‘ear of corn’ What is interesting about this ‘centre’ meaning is that it gives way to another conceptual metaphor IMPORTANT IS CENTRE. In many languages, this metaphor exists too (e.g. the core argument); but, as discussed above, the head, understood as the top part, seems to be related to the metaphor IMPORTANT IS UP instead. However, Basque presents an interesting case in point; this language has the same source domain, head, but it is a different interpretation of head what seems to trigger this metaphor. There are numerous examples that prove that the head is centre and that this is considered the most important, but I will mention just two cases since they can show us that cultural information is a ‘must’ in this type of studies. One example is the word etxeburu (house.head). Here again, one could think that this could be the upper part of the house, but in Basque, this is interpreted as ‘the most important part of the house façade’; in fact, as shown in (4), this is the place where the coat of arms is located. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language (4) 12 Etxe-buru-an harmarria dago house-head-LOC coat.of.arms-ABS is ‘There is a coat of arms at the ‘head’ of the house façade’ But where exactly is the coat of arms located? In traditional Basque houses, they were located just at the centre of the house façade, right in the middle as can be seen in Figure 1. Figure 1: Buru and IMPORTANT IS CENTRE. Another example is the word buruzagi ‘leader, chief’,8 as illustrated in (5). (5) Preso sartu aitzin, Praga-ko komunist buruzagi 8 This is the most common usage nowadays, and one of the oldest as well (first documented in 1167, see Mitxelena 1987-2005: 850, and Michelena 1990: 47, Zaldua Etxabe 2006: 54), but it should be taken into account that this word has other translations too such as ‘foreman, main ranger, shepherd, boss, owner’. In all of them, nevertheless, the common characteristic is that it refers to somebody or something (hiri buruzagi ‘capital city’) of importance. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language prisoner enter before praga-ADN 13 communist leader nagusi-etarik zen main-PART AUX ‘Before he was imprisoned, he was one of the main leaders of the Communist Party in Prague’ Without anthropological information, one could presume that buruzagi is grounded on exactly the same orientational vertical scale as English head of …, and thus, that the underlying metaphor is IMPORTANT IS UP. However, one should take into account that in ancient Basque culture, clan members seem to be represented in small stone circles. Each stone represented one member and one duty, and the chieftain was represented with another stone at the centre of the circle (Frank p.c., see also Ott 1993, Zaldua Etxabe 2006). In other words, the hierarchical structure was not pyramidal, and therefore, the head was not situated at the top of the pyramid but at the centre. The body-part begi ‘eye’ is another rich polysemous word in Basque. Begi ‘eye’ develops interesting metaphorical and metonymical meanings such as ‘hole’ in erlategiren begia ‘hive entrance’, ogibegi ‘holes in bread’, gaztabegi ‘holes in cheese’ and ‘hook’ in orratzaren begia ‘eye of a needle’, aitzurbegi ‘hoe hole’. It is important to notice that, despite its similarities with English eye (especially if one looks at the translation), these two begis are conceptualised differently. While the former, erlategiren begia, ogibegi and gaztabegi, focus on the hole conceptualisation (rounded empty cavity where the eye lies), the latter do not just emphasise the hole in these gadgets, but their function; that is, it is not just a question of entering and exiting, but of doing so and staying put there. What begi implies in these latter expressions (orratzaren begia, aitzurbegi) is that these cavities are not only to be Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 14 crossed through but also to keep the entity that passes through there. It is easy to prove that these two meanings are conceptualised separately. There is one test to prove it so: the word aho ‘mouth’. This body-part can also be used with the meaning ‘hole’, and therefore, one can say erlategiaren begia or erlategiaren ahoa ‘hive entrance’, but this interchangeability is not allowed in the latter group; orratzaren ahoa, for example, means the poiting end of needle not the eye of the needle. There are other metaphors related to begi ‘eye’ such as SMALL QUANTITY IS AN EYE as in (6), where begi almost functions as a quantifier: (6) Handi begia (big eye.ABS) ‘biggish’ Begi bete (bat) ardao emon eye full (one) wine give.PFV eusten AUX ‘They gave me a little bit of wine’ But there is one metaphorical case that I would like to focus on because, once again, it shows that the conceptualisation of eye in Basque does not necessarily correspond to the conceptualisation of this body-part in other languages. The word begi develops a case of the DIRECTION IS ORIENTATION metaphor as illustrated in (7): (7) Itsaspegi (sea.eye) ‘looking/facing towards the sea’ Eguzki begi(-an) (sun-eye(-LOC)) ‘looking/facing towards the sun’ As Garai (2002) argues, the orientation of the face/eyes is related to ‘attention’ and ‘intention’. Our eyes can move freely to any direction (cf. direct one’s eyes), and this capacity is reflected in examples in (7). However, what is interesting about this Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 15 metaphor comes from its relation to buru ‘head’. Basque buru ‘head’ and begi ‘eye’ can be considered opposite body-parts (similarly to ‘head and tail’, or ‘head and foot’ in some languages). The word buru ‘head’ in Basque also develops the meaning ‘in the direction of’ as illustrated in example (8): (8) Mendi-ari buru-z mountain-DAT head-INST abiatu ginen go.PFV AUX ‘We went towards the mountain’ One could argue that begi ‘eye’ and buru ‘head’ could be synonyms here, that they develop the same semantic extensions. However, this is not true because the entities that play a role as figure and ground in these situations are not the same. begi buru Figure Ground Ground Figure Figure 2: Figure and gound in begi ‘eye’ and buru ‘head’ In the case of buru ‘head’, the ‘mountain’ plays the role of the ground and ‘we’ are the figure that moves towards that direction. In the case of begi ‘eye’, on the other hand, there is a figure-ground reversal, the ‘mountain’ is the figure and ‘we’ the ground. These different conceptualisations are schematised in Figure 2. The other external body-part that I will touch upon in this section is oin ‘foot’. This body-part, on the basis of an anthropomorphic model, is usually related to lower Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 16 spatial location as in English at the foot of the mountain. Once again, a similar interpretation could be applied to Basque oin ‘foot’ as in (9): (9) mendi-aren oin-ak (mountain-GEN foot-ABS.PL) ‘the feet of the mountain’ However, the link between foot and bottom does not seem to be very strong in Basque; instead, this type of expressions activate the notion of ‘support’ rather than ‘lower-part’ and (9) can be therefore paraphrase as ‘the area that supports or functions as the basis for the whole mountain’. This reading gives rise to the metaphor FOUNDATION IS SUPPORT (10) as illustrated in (11): Oinarri-z-ko teoria (foot.stone-INST-ADN theory) ‘Basic theory’ Ekonomia-ren oinarri-ak (economy-GEN foot.stone-ABS.PL) ‘the basis of economy’ And also to the metaphor PERSISTING IS REMAINING ERECT (Grady 1997) as shown in (11): (11) …mantendu gura da bere oin-ean andikeria keep.PFV want AUX his foot-LOC arrogance.ABS ‘He wanted to keep his arrogance’ 2.2. Emotions and Internal body-parts: gibel ‘liver’, and bihotz ‘heart’ Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 17 In the previous section, I have examined a few external body-parts, buru ‘head’, begi ‘eye’ and oin ‘foot’, and its metaphorical extensions into the domain of space. In this section, I would like to draw our attention to a couple of internal body-parts, gibel ‘liver’ and bihotz ‘heart’, and its metaphorical extensions into the domain of emotions. This does not mean that both gibel ‘liver’ and bihotz ‘heart’ do not develop spatial meanings; they do indeed. Gibel ‘liver’ can convey the meaning ‘back side, rear side’ as in (12) and bihotz ‘heart’ can be used in the sense of ‘core, inside part of something’ as in (13): (12) Etxe-aren gibel-ean (house-GEN liver-LOC) ‘at the rear part of the house’ Gibel egin (liver make.PFV) ‘move backwards’ (13) Hezurr-aren bihotz-a (bone-GEN heart-ABS) ‘bone marrow’ Sagarr-aren bihotz-a (apple-GEN heart-abs) ‘apple’s core’ These spatial meanings give rise to further metaphorical developments as well. Gibel ‘liver’ can be interpreted as time reference following the metaphor TIME IS SPACE. It is always related to ‘delay, be late’ as in gibel-du (liver-verbal suffix) ‘be late’. Interestingly enough, gibel ‘liver’ seems to always be related to negative values as in the word gibelondo (liver.near) ‘(bad) result consequence’, and it can be considered the opposite to begi ‘eye’ in contexts where the meaning is ‘neglect’ as in gibel eman (liver give.PFV) ‘turn one’s back to sb’. The ‘core, internal’ meaning of bihotz ‘heart’ is the basis for the metaphor CENTRAL IS IMPORTANT as in hiri-aren bihotz-a (city-GEN Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 18 heart-ABS) which refers to the most important part of the city, but with the connotation that it is the place where everything happens. As far as emotions are concerned, the body-part bihotz ‘heart’ shows a wide and rich array of different types of emotions, both positive and negative. Bihotz ‘heart’ is usually associated with: • positive feelings in general as in bihotz-ak egin (heart-ERG make.PFV) ‘be moved’, • love as in bihotz-bihotz-ez (heart-heart-INST) ‘with all my love’, • encouragement as in bihotz-ari egin (heart-DAT make.PFV) ‘encourage’, • generosity as in bihotz-zabal (heart-wide) ‘generous’, • mercy as in bihotz-biguin (heart-soft) ‘tender, compasionate’, • braveness as in bihoztun (heart.possessor) ‘brave, bolt, gallant’. Most of these meanings are well-attested in Western culture, probably due to a common religious and/or classical cultural background (see Garai 2001, 2002, Malina 1993). Bihotz ‘heart’ is also linked to negative feelings such as: • cruelty as in bihozgogor (heart.hard) ‘hard-hearted’, • cowardice as in bihotz-urri (heart-scarce) ‘coward’, • sadness as in biotzil (heart.die) ‘sadness’, • anguish as in bihozmin (heart.pain) ‘grief’, • remorse as in bihotz zimiko (heart pinch) ‘remorse, regret’, • discourage as in bihozkatu ‘lose courage’, • anger as in bihotzerra (heart.fire) ‘anger’. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 19 However, it is important to bear in mind that in most of these cases, the negative reading is triggered not by bihotz ‘heart’ itself, but by a negative word that denotes the lack of heart as in bihozgabe (heart.without) ‘cruel’ or a negative quality itself as in bihotz-apal (heart-weak) ‘coward’. The body-part gibel ‘liver’, on the other hand, is always related to negative emotions: • listlessness as in gibelhandi (liver.big) ‘slow, sluggish, carefree’, • mistrust as in gibel-etik ibili (liver-ABL walk.PFV) ‘act surreptitiously’, • disdain as in gibelondo (liver.side) ‘scorn’, • aversion as in gibelgogo ‘antagonism, hostility’, • withdrawn character as in gibelkoi ‘shy, bashful’, • bitterness, rancour as in gibelmin (liver.pain) ‘spite’. Although more research should be carried out in this respect, it is possible to argue that these negative emotions in gibel ‘liver’ may be grounded on different conceptual bases. Emotions such as listlessness, mistrust, disdain, aversion, and introverted character may arise from the conceptualization of gibel as ‘back’. Human beings rely on their eyes much more than on any other sense (cf. Classen 1993, Howes 1991, Sekuler and Blake 1994). The eyes provide the most reliable information and give us the highest degree of security. This is why we do not trust things that we do not see, and why we have expressions such as seeing is believing (cf. Danesi 1990, Sweetser 1990). Consequently, anything that falls outside the scope of our eyes is generally considered negative, or at least, untrustworthy. All of the emotions mentioned above reflect the unreliable and treacherous character of the ‘back’, understood as the area Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 20 hidden from the eyes. Emotions such as bitterness, rancour, and spite may arise from the conceptualisation of gibel as ‘bile’ instead. This is, of course, related to the ancient physiological-psychological theory of the four humours where an abundance of yellow bile results in a choleric temperament (see Geeraerts and Grondelaers 1995, Hoskin 1962, Jones 1979, Loudon 1997). 2.3. Intellect, emotions and body-parts: buru ‘head’, bihotz ‘heart’, and the cultural word gogo In this final section, I would like to concentrate on one of the most common dichotomies in Western culture, the separation between intellect and emotion, as it is reflected in well-known pairs such as ‘body and soul’, ‘heart and mind’, etc. In Western philosophy, especially in Cartesian dualism, there is a clear-cut division between the mind, that is, the locus for rational thinking, consciousness, intelligence, and common sense,9 and the heart, the place for the physical, irrational passions and desires. This connection between head and mind, and heart and emotion is also found in Basque in the words already analysed in this paper. As shown above, bihotz ‘heart’ is related to different kinds of emotions but it is also understood as the seat of positive general feelings. Buru ‘head’ is linked to the mind as illustrated in (14): (14) Buruargi (head.light) ‘intelligent, clever’ Burugabe (head.without) ‘idiot’ Buru-ra etorri (head-ALL come.PFV) ‘to occur, to remember’ Buru-an izan (head-LOC be.PFV) ‘to have in mind’ 9 The relationship between head and mind can also be understood as a metonymy-based metaphor (see Barcelona 1997, Pascual-Aransáez 1998-1999). Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 21 Buru-an sartu (head-LOC enter.PFV) ‘to understand’ Buru-tik bota (head-ABL throw.PFV) ‘to forget’ However, this dualism is challenged in other cultures. Authors such as Yu (2008) have shown that in Chinese both faculties are actually embodied in one single concept xin ‘heart’, and others such as Siahaan (2008) have argued that different body-parts such Indonesian hati ‘liver’ represent in themselves what Western culture knows as heart and mind (see also papers within Sharifian et al. 2008). In other words, there are many cultures in which this well-known dichotomy does not hold. Judging from what has been discussed about, Basque is among those languages in which emotion is associated with the heart and intellect with the head. In other words, Basque also conceptualizes the rational and irrational sides of the body as two separate entities. However, this is not the whole story. Basque has a special word, gogo, that contradicts this Cartesian duality, and might be compared to other cases (cf. xin and hati) where both sides, emotion and mind, are united under the same organ or entity. Gogo (goga- in some compounds) is considered a word deeply entrenched in the language (Agud and Tovar 1992) and a peculiar concept in Basque mentality (Goenaga 1971). Although several proposals have been put forward about its etymological origin (see Agud and Tovar 1992), it is generally agreed that it is a native Basque word and possibly the result of a(n) (expressive) reduplication (Trask 2008: 207). Gogo is a perfect example of what cultural words are meant to be, that is, specific conceptualisations of the world which are peculiar to a given cultural community and comprise all lexical items grounded in one specific culture. Cultural Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 22 words are language vehicles to discover deep conceptualisations in culture and thought. It is important to bear in mind that Basque is a language that has always been in contact with other languages and cultures. However, until the twentieth century, its transmission was almost exclusively oral. Its written tradition is relatively young compared to that of other European languages. Moreover, the earlier pretwentiethcentury texts were almost always composed explicitly for religious purposes (Oyharçabal 2001). For this reason it is sometimes very difficult to distinguish between conceptualizations that are native to the Basque language and its culture (prior to contact, say, with Christianity), and those conceptualizations that have been acquired through contact with other languages and cultures. There are, nevertheless, some expressions and usages that now and then reveal and corroborate that Basque used to have its own conceptualizations and unique worldview. These words are usually ubiquitous, very much entrenched in culture and thus, very difficult to explain and translate into other languages. I would like to argue that gogo is one of such words. What is interesting about gogo for the discussion on Cartesian dichotomies is that gogo does not separate the rational from the irrational; quite on the contrary, in gogo these two apparent opposites are ‘melted’ or ‘blended’. Gogo is used to describe emotions such as those in (15), but also to convey characteristics and processes associated with the mind such as those in (16). (15) Gogoalai (gogo.happy) ‘jovial, cheerful’ Gogo-a argitu (gogo-ABS clear) ‘cheer up’ Gogo-a berotu (gogo-ABS heat.PFV) ‘encourage’ Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 23 Gogo-a urritu (gogo-ABS dwindle.PFV) ‘become disheartened, discouraged’ Gogobero (gogo.hot) ‘zeal, fervor, enthusiasm’ Gogo bete (gogo full) ‘disgust, satiation’ Gogomin (gogo.pain) ‘ardent desire, passion, yearning’ Gogo-ak izan (gogo-ABS.PL have.PFV) ‘feel like’ Gogohandi (gogo.big) ‘magnanimous, generous’ (16) Gogo argi (gogo light) ‘bright mind’ Gogonahasi (gogo.mix) ‘scatterbrain’ Gogamen ‘intelligence’ Gogoeta ‘thought’ Gogo aldatu (gogo change.PFV) ‘change one’s mind’ Gogoratu (gogo.ALL.PFV) ‘remember’, ‘occur to, think of’ Gogo-an izan (gogo-LOC be.PFV) ‘remember’ Gogo-ra ekarri (gogo-ALL bring.PFV) ‘recall, remember bring to mind’ Gogo-ari eman (gogo-DAT give.PFV) ‘imagine’, ‘think’, ‘decide’ These examples show that gogo harmoniously unites these two apparent contrary concepts in one; in a way, gogo is a kind of primitive thought or rational soul, where there is an intellectual reasoning process, but one based on intuition and emotion; or to put it in another way, an intellectual reasoning process prior to any distinctions between feelings and thought – which, in fact, implies that reason and feelings are not differentiated at all. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 24 The word gogo in some of the expressions in (15) and (16) can be substituted by bihotz ‘heart’ and buru ‘head’. Just to name a couple of pairs: gogoa galdu and bihotz galdu ‘become discouraged’, gogohandi and bihotzhandi ‘magnanimous, generous’, gogoratu and bururatu ‘remember, think of’, gogoargi and buruargi ‘intelligent’… However, despite this interchangeability, the connotations are not the same, gogo goes beyond the simple intellectual or emotional process, because it is both at the same time. Goenaga (1971, 1972, 1973), one of the authors that has studied the use of this word by classical traditional Basque writers, describes this word as: The act of faith carried out by gogo is not just the result of intelligence, but also an act in which all sorts of emotional influence take place, from affectivity to intelligence with the intervention of will (Goenaga 1971b: 28, my translation) Even if the heart represents the affective side, gogo includes not only thought but also all the impulsive side of personality which is precisely what drives human beings and the way they are. Besides, in all Basque literature, the pair gogo-bihotz do not seem to be two different members but two members in which gogo points to the whole and bihotz to the part (Goenaga 1973a: 204, my translation) Gogo is not a physical organ like xin or hati, but it is something internal to the self, something so basic and so deeply human, that represents all what is important to humans, their body and soul. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 25 3. Conclusions: Reasons why conceptual metaphors should be studied In this paper, I have examined some of the main metaphorical extensions related to the domains of space, intellect and emotions in the Basque body-parts: buru ‘head’, begi ‘eye’, oin ‘foot’, bihotz ‘heart’, and gibel ‘liver’. This analysis has shown that some of these Basque body-parts present similar conceptualisations to those bodyparts in other languages. For example, bihotz is related to feelings and buru is linked to top and front regions. However, there are important differences among these conceptualisations too. One of the main differences is that some body-parts have different meanings, for example, gibel is associated to the back region and buru is not only related to the top and front regions, it also means central. Another difference is that some apparently similar metaphorical expressions are not grounded on the same concepts. The relationship between top region and important, the IMPORTANT IS UP metaphor, does not hold in Basque. Buru can sometimes mean ‘top’ depending on the context, but, contrary to what happens in many languages, this contextually dependent meaning of ‘top’ does not give rise to this metaphor in Basque. This language prefers the central meaning of buru as the conceptual basis for the metaphor IMPORTANT. CENTRAL IS Yet another difference is that although some body-parts might convey similar meanings, these meanings can be richer in connotations in some languages than others. This is the case of oin ‘foot’, which is not only linked to the ‘bottom’ area but also the notion of ‘support’. Finally, it has been shown that, even in languages such as Basque that have been in contact with other languages and cultures, there are always certain special cultural words such as Basque gogo that reveal deeply entrenched metaphors that teach us a little bit more about ancient native worldviews. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 26 These cases are all very important, not only because they show differences within the conceptualisation of body-parts in Basque with respect to other languages, but also because they clearly warn us against any kind of “linguacentrism”, as Palmer (2003) would call it. If we aim at discovering the grounding of conceptual metaphors, the cultural background in which these metaphors are embedded needs to be dug out; otherwise, all we will have is a distorted picture of what really happens in a language. This is why metaphor theory needs culture. However, this need is mutual. Culture also needs metaphor, because it is a systematic way to unveil certain pieces of cultural information and to compare them with other cultures and languages. The relationship between body-parts and space, intellect, and emotion is universal, but the metaphorical connections between and within these domains are not necessarily the same. Finally, the last question I would like to touch upon is the need to incorporate metaphor in the study of endangered languages. We all, as linguists, know that the most endangered ‘species’ in the world nowadays are not the fish, the plants, the birds or the mammal, but the languages (Sutherland 2003). Languages are living creatures, and of course, death is part of their natural cycle of life. However, the accelerating extinction of languages is much faster than that of any other species, and it is happening on a global scale. Linguists always preoccupied about the disappearance of languages have been engaged in collecting and describing the grammars of dying languages in an attempt to preserve some of the rich linguistic diversity of the world. As Dixon (2010) recommends in his first volume of Basic Linguistic Theory, when talking about the best methodology for any linguist interested in describing and analysing languages, linguists should describe the abstract systems of phonology and grammar [morphology and syntax]. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 27 However, when a language dies it is not only its sounds, its morphemes, its complex structures and its lexemes that die, what disappears is a whole unique worldview. If a language like Basque dies, we do not only loose a list of words for body-parts but all the metaphorical conceptualisations within these words. Therefore, researchers on endangered languages should consider metaphors as part of their data collection list. The reasons are clear. As Harrison (2007: 7, 17, 19) puts it (see also Evans 2010, Harrison 2010): Language disappearance is an erosion or extinction of ideas, of ways of knowing, and ways of talking about the world and human experience […] We stand to lose the accumulated wisdom and observations of generations of people about the natural world, plants, animals, weather, soil, and so on […] The loss of even one language may forever close the door to a full understanding of human cognitive capacity. All of this knowledge, all of this wisdom about the world around us, and all of this understanding about human cognition is reflected in metaphors, and this is why metaphors should be a must for any piece of linguistic work that attempts to unveil what a language is, how a language works, and why a language is needed for. References Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 28 Agud, Manuel and Tovar, Antonio. 1992. “Materiales para un diccionario etimológico de la lengua vasca”. Anuario del Seminario de Filología Vasca ‘Julio de Urquijo’ XXVI (2): 645-694. Alm-Arvius, Christina. 1993. The English Verb See: A Study in Multiple Meaning. Göteborg: Acta Universitas Gothoburgensis. Baker, Colin E. 1999. Seeing Clearly: Frame Semantic, Psycholinguistics, and Crosslinguistic Approaches to the Semantics of the English Verb See. Unpublished Ph.D. thesis. University of California at Berkeley. Barcelona, Antonio. 1997. “Clarifying and applying the notions of metaphor and metonymy within Cognitive Linguistics”. Atlantis XIX (1): 21-48. Caballero, Rosario and Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide. In press. “Ways of perceiving and thinking: Re-vindicating culture in conceptual metaphor research”. Companion of Cognitive Semiotics. Chrisley, Ron and Ziemke, Tom. 2002. “Embodiment”. In Encyclopedia of Cognitive Science, Lynn Nagel (ed), 1102-1108. London: Macmillan. Classen, Constance. 1993. Worlds of Sense: Exploring the Senses in History and Across Cultures. London: Routledge. Croft, William and Cruse, David A. 2004. Cognitive Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Danesi, Marcel 1990. “Thinking is Seeing: Visual Metaphors and the Nature of Abstract Thought”. Semiotica 80 (3/4): 221-37. Dixon, R.M.W. 2010. Basic Linguistic Theory. Volume 1: Methodology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Dobrovol’skij, Dimitri and Piirainen, Elisabeth. 2005. Figurative language: crosscultural and cross-linguistic perspectives. Amsterdam: Elsevier. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 29 Evans, Nicholas. 2010. Dying Words: Endangered Languages and What They Have to Tell Us. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. Evans, Vyvyan and Green, Melanie. 2006. Cognitive Linguistics. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. Evans, Nick and Wilkins, David. 2000. “In the Mind’s Ear: The Semantic Extensions of Perception Verbs in Australian Languages”. Language 76 (3): 546-92. Garai, Koldo J. 2001. “Epaiketa eta endogamia Nafarroako Margaritaren Le Miroir de l’amé pécheresse-n [Anima Bekatariaren Mirailan]”. Lapurdum VI: 119-193. Garai, Koldo J. 2002. “Limurketa eta esanguraren arteko harremanak Euskal atsotitzetan”. Gogoa II (2): 227-287. Geeraerts, Dirk and Cuyckens, Hubert (eds). 2008. Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Geeraerts, Dirk and Grondelaers, Stefan. 1995. “Cultural traditions and metaphorical patterns”. In Language and the Construal of the World, John R. Taylor and Robert E. MacLaury (eds.), 153-179. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Goenaga, Angel. 1971a. “Gogo en Dechepare”. Fontes Linguae Vasconum 7: 15-23. Goenaga, Angel. 1971b. “Gogo en refranes antiguos”. Fontes Linguae Vasconum 7: 25-34. Goenaga, Angel. 1971c. “Gogo en Tartas”. Fontes Linguae Vasconum 8: 181-19. Goenaga, Angel. 1972. “Gogo en Leiçarraga”. Fontes Linguae Vasconum 11: 229260. Goenaga, Angel. 1973a. “Gogo en Axular”. Fontes Linguae Vasconum 14: 185-244. Goenaga, Angel. 1973b. “Gogo en Oihenart”. Fontes Linguae Vasconum 14: 245-260. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 30 Gorostiaga, Juan. 1982. “El fondo primitivo de la lengua vasca”. Fontes Linguae Vasconum 39: 105-132. Grady, Joseph. 1997. “THEORIES ARE BUILDINGS revisited”. Cognitive Linguistics 8 (4): 267-299. Harrison, David K. 2007. When Languages Die. The Extinction of the World’s Languages and the Erosion of Human Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Harrison, David K. 2010. The Last Speakers. The Quest to Save the World’s Most Endangered Languages. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. Heine, Bernd. 1989. “Adpositions in African languages”. Linguistique Africaine 2: 77-127. Holland, Dorothy and Quinn, Naomi (eds.). 1987. Cultural Models in Language and Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Hoskin, M. A. 1962. History of Science. New York: Science History Publications. Howes, David (ed.). 1991. Varieties of Sensory Experience: A Sourcebook in the Anthropology of the Senses. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Hualde, José Ignacio and Ortiz de Urbina, Jon (eds.). 2003. A Grammar of Basque. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide. 1999. “Metaphorical Mappings in the Sense of Smell”. In Metaphor in Cognitive Linguistics, Raymond W. Jr. Gibbs and Gerard J. Steen (eds.), 29-45. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide. 2002a. “MIND-AS-BODY as a Cross-linguistic Conceptual Metaphor”. Miscelánea. A Journal of English and American Studies 25: 93119. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 31 Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide. 2002b. “The conceptual structure of Basque buru ‘head’”. Fontes Linguae Vasconum 91: 465-493. Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide and Garai, Koldo J. 2004. “Basque body parts and their conceptual structure: the case of oin ‘foot’ and begi ‘eye’”. In Linguagem, cultura e cognição: estudos de lingüística cognitiva. 2 vols, Augusto Soares da Silva, Amadeus Torres, Miguel Gonçalves (eds.), 269-291. Coimbra: Almedina. Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide. 2008a. “Vision metaphors for the intellect: Are they really cross-linguistic?” Atlantis 30(1): 15-33. Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide. 2008b. “Guts, heart, and liver: The conceptualisation of internal organs in Basque”. In Language, Body, and Culture: Cross-linguistic Conceptualizations of Internal Body Organs, Farzad Sharifian, René Dirven, Ning Yu and Susanne Niemeier (eds.), 103-128. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide. In preparation. “Cultural words in metaphor and translation: The case of Basque gogo”. Johnson, Mark. 1987. The Body in the Mind. The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Reason and Imagination. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Jones, W. H. S. 1979. Philosophy and Medicine in Ancient Greek. New York: Arno Press. Kahr, Joan Casper. 1975. “Adpositions and locations: Typology and diachronic development”. Working Papers on Language Universals 19: 21-45. Kövecses, Zoltán. 2005. Metaphor in Culture. Universality and Variation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 32 Lakoff, George and Johnson, Mark. 1980. Metaphors We Live by. Chicago: Chicago University Press. Lakoff, George and Johnson, Mark. 1999. Philosophy in the Flesh. The Embodied Mind and its Challenge to Western Thought. New York: Basic Books. Loudon, Irvin. 1997. Western Medicine. An Illustrated History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Malina, B. J. 1993. The New Testament World: Insights from Cultural Anthropology. Louisville, KT, Westminster: John Knox Press. Meillet, Antoine. 1912. Linguistique Historique et Linguistique Genérale. Paris: Klincksieck. Michelena, Luis. 1990 [1964]. Textos Arcaicos Vascos. Madrid: Minotauro. Mitxelena, Koldo. 1987-2005. Diccionario General Vasco. Orotariko Euskal Hiztegia. Bilbao: Euskaltzaindia. Moseley, Christopher (ed.). 2010. Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, 3rd ed. Paris: UNESCO Publishing. Online version: http://www.unesco.org/culture/en/endangeredlanguages/atlas. Accessed January 11, 2011. Nerlich, Brigitte, Todd, Zazie, Herman, Vimala and Clarke, David (eds.). 2003. Polysemy. Flexible Patterns of Meaning in Mind and Language. New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Ong, Walter J. 1991. “The Shifting Sensorium”. In The Varieties of Sensory Experience. A Sourcebook in the Anthropology of the Senses, David Howes (ed.), 25-30. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. Ott, Sandra. 1993. The Circle of Mountains: A Basque Shepherding Community. Reno: University of Nevada Press. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 33 Oyharçabal, Beñat. 2001. “Statut et evolution des letters basques durant les XVIIème et XVIIIème siécles”. Lapurdum VI : 219-287. Palmer, Gary B. 2003. “Introduction”. Cognitive Linguistics 14(2/3): 97-108. Palmer, Gary B. and Sharifian, Farzad. 2007. “Applied cultural linguistics: An emerging paradigm”. In Applied Cultural Linguistics, Farzad Sharifian and Gary B. Palmer (eds.), 1-14. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Pascual-Aransáez, Cristina. 1998-99. “The role of the head in the conceptualisation of rational behaviour: A cross-linguistic study of the metaphorical expressions of the folk model of the head”. RESLA, Revista Española de Lingüística Aplicada 13: 113-124. Rijk, Teun, de. 2008. Standard Basque. A Progressive Grammar. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press. Rohrer, Tim. 2001. “Pragmatism, ideology and embodiment: William James and the philosophical foundations of cognitive linguistics”. In Language and Ideology, vol I: Theoretical Cognitive Approaches, René Dirven, Bruce Hawkins and Esra Sandikcioglu (eds), 49-81. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Santiago, Julio, Román, Antonio and Ouellet, Mark. In press. “Flexible foundations of abstract thought: A review and a theory”. In Spatial dimensions of social thought, A. Maas and T. Schubert (eds). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. Sekuler, Robert and Blake, Randolph. 1994. Perception. New York: McGraw-Hill. Sharifian, Farzad. 2003. “On cultural conceptualisations”. Journal of Cognition and Culture 3 (3): 1987-2007. Sharifian, Farzad and Palmer, Gary B. (eds.). 2007. Applied Cultural Linguistics. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 34 Sharifian, Farzad, Dirven, René, Yu, Ning and Niemeier, Susanne (eds.). 2008. Culture, Body, and Language. Conceptualizations of Internal Body Organs across Cultures and Languages. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Siahaan, Poppy. 2008. “Did he break your heart or your liver? A contrastive study on metaphorical concepts from the source domain ORGAN in English and in Indonesian”. In Culture, Body, and Language. Conceptualizations of Internal Body Organs across Cultures and Languages, Farzad Sharifian, René Dirven, Ning Yu and Susanne Niemeier (eds.), 45-74. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Sinha, Chris and Jensen de Lopez, Kristine. 2000. “Culture and the embodiment of spatial cognition”. Cognitive Linguistics 11: 17-41. Sutherland, William J. 2003. “Parallel extinction risk and global distribution of languages and species”. Nature 423: 276-279. Svorou, Soteria. 1993. The Grammar of Space. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Sweetser, Eve. 1990. From Etymology to Pragmatics. Metaphorical and Cultural Aspects of Semantic Structure. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Trask, R. L. 1997. A History of Basque. London: Routledge. Trask, R. L. 2008. “Etymological dictionary of Basque”. University of Sussex Linguistics and English Language Working Paper LxWP 23/08. Available at http://www.sussex.ac.uk/linguistics/1-4-1-2.html. Accessed August 12, 2011. Tyler, Stephen. 1984. “The Vision Quest in the West or What the Mind’s Eye Sees”. Journal of Anthropological Research 40: 23-40. Valenzuela, Javier. 2009. “What empirical work can tell us about primary metaphors?”. Quaderns de Filologia. Estudis lingüístics XIV: 235-249. Unveiling conceptual metaphors in a minority language 35 Viberg, Ake. 2008. “Swedish verbs of perception from a typological and contrastive perspective”. In Languages and Cultures in Contrast and Comparison, María de los Ángeles Gómez González, J. Lachlan Mackenzie and Elsa M. González-Álvarez (eds.), 123-172. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Violi, Patrizia. 2004. “Embodiment at the crossroads between cognition and semiosis”. Recherches en communication 19: 199-217. Violi, Patrizia. 2008. “Beyond the body: Towards a full embodied semiosis”. In Body, language, and mind: Vol. 2. Sociocultural situatedness, Roslyn Frank, René Dirven, Tom Ziemke, and Enrique Bernárdez (eds.), 53-76. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Wilson, Michael. 2002. “Six Views of Embodied Cognition”. Psychological Bulletin and Review 9 (4): 625-36. Yu, Ning. 2008. “The Chinese heart as the central faculty of cognition”. In Culture, Body, and Language. Conceptualizations of Internal Body Organs across Cultures and Languages, Farzad Sharifian, René Dirven, Ning Yu and Susanne Niemeier (eds.), 131-168. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Yu, Ning. 2009. From Body to Meaning in Culture. Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins. Zaldua Etxabe, Luis Mari. 2006. Saroiak eta kortak. Mendialdeko antzinako gizartearen oinordeak. Urnieta. Ziemke, Tom. 2003. “What’s that Thing Called Embodiment”. In Proceedings of the 25th Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, Richard Alterman and David Kirsh (eds.), 1305-1310. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.