CAMPOS DE CASTILLA Antonio Machado

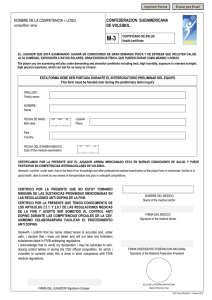

Anuncio