«Of Sailors and Savages» : Tierra del Fuego and Magellan Strait

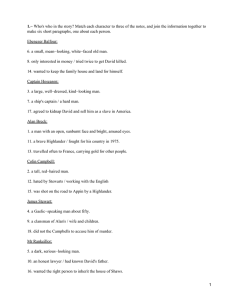

Anuncio