Verb Meaning in Context Alexandra Anna Spalek Universitat

Anuncio

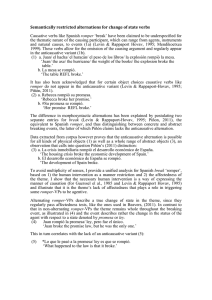

Verb Meaning in Context Alexandra Anna Spalek Universitat Pompeu Fabra MOTIVATION: The study of verbs within formal linguistics has focused mainly on the relation between verb meaning and diathesis alternation (Levin, 1993), (Hale & Keyser, 1993), (Levin & Rappaport Hovav, 1995), (Alexiadou, 2010) leaving aside the equally pressing question of how to account for the pervasive differences in argument selection possibilities, which trigger polysemy. Verbs like Spanish romper (break) appear in a bewildering range of contexts; for this reason dictionaries easily split their meanings into as many as 20 to 30 senses (Real Academia Española). But if this kind of variation in context is the rule rather than the exception, the question that arises is: What does the range of possible contexts tell us about the verb’s meaning itself, and is there a way to account for them avoiding positing so many senses? The goal of this research is to explore the relation between the different uses of the verb break as shown in example (1) – (4), and question if verb meaning actually varies as much as it might seem from a simple look at a dictionary entry. (1) Los manifestantes rompieron una ventana. The demonstrators broke a windows. The demonstrators broke a window. (2) México rompió relaciones diplomáticas con Cuba. Mexico broke relations diplomatic with Cuba. Mexico broke diplomatic relations with Cuba. (3) La propuesta del Gobierno rompe una larga tradición. The proposal of government breaks a long tradition. The Government’s proposal breaks a long tradition. (4) El astronauta rompió el récord de permanencia en un transbordador. The astronaut broke the record of permanence in a shuttle. PROCEDURE: The basic idea is that the multiplicity of senses can be reduced by abstraction from detailed observation of verbs in context. Based on Asher and Lascarides (2001), we assume that semantically delimited groups of verbs, namely the much-studied class of change of state verbs (Rappaport Hovav & Levin, 2002) share some consistent semantic components, also called core meaning (Rappaport Hovav & Levin, 1998), which is preserved in most of its uses. Our study explores how the verbs’ core meaning must look like if we want to account for the variety of theme arguments that break can take. We observed break in a 250.000.000 word Spanish press corpus by applying the Corpus Pattern Analysis methodology (Hanks, 2011), which allowed us to track in great detail the syntactic and semantic behavior of a verb. By grouping verb concordances into syntactic patterns and assigning each argument a semantic class label just like [Human], [Physical Object], we obtained a detailed picture of the selectional preferences of break. PROPOSAL: Our corpus observation revealed that the meaning of break is affected very importantly by the semantics of the theme argument. While change of state predicates, in general, applied to physical objects denote the change in material integrity of the objects, the meaning of “alteration of the integrity” is not necessarily triggered with abstract themes. Thus examples (2) – (4) describe the cessation of the state when an agreement, a tradition or a record were holding, rather than the disintegration or destruction of these abstract objects. In addition, COS verb combinations with abstract themes have more limited possibilities of taking natural causes and instruments as causers, as illustrated in examples (5) – (8). This, in turn, correlates with the very recent observation by Rappaport-Hovav and Levin (2011) that the choice of subject varies with the choice of the object and that these subject-object interdependencies follow basically form non-lexical factors, which determine when a cause can be found with verbs that are to be taken as basically monadic. (5) [Human / Natural Cause/ Instrument] romper [Physical Object] El manifestante/ el viento/ la piedra rompieron una ventana. The demonstrator/ the wind/ the stone broke a window. (6) [Human / Institution/ ?Natural Cause/ ?Instrument] romper [Relation] El presidente/ México/ ?el viento/ ?la piedra rompió las relaciones diplomáticas con Cuba. The president/ Mexico/ *the wind/ *the stone broke the diplomatic relations with Cuba. (7) [Human/ Act/ Dot Object/ ?Natural Cause/ ?Instrument] romper [Tradition] El gobierno/ las propuesta/ ? el veinto/ ?la piedra rompe una larga tradición. The government/ the proposal/ *the wind/ * the stone breaks a long tradition. (8) [Human/ ?Institution/ ?Natural Cause/ ?Instrument ] romper [Limit] El astronauta/ ?México/ ?el viento/ ?la piedra rompió el récord de permanencia en un transbordador. The astronaut/ ?Mexico/ *the wind/*the stone broke the record of permanence in a shuttle. In general, across the uses of break only a very abstract notion of ‘cession of a state’ is preserved, and it is the particular selectional context, and specially the theme argument, which concretes more details about the event. These facts support two conclusions: 1. Break is better understood as a very general change of state verb that simply brings about the cessation of a holding state, rather than a verb of material disintegration. 2. Despite our naïve intuition that verbs describe very concrete events, the meaning of the verb itself is actually quite abstract and only becomes fleshed out in combination with its arguments. KEY WORDS: lexical semantics, polysemy, change of state verbs. SELECTED REFERENCES: ALEXIADOU, A. (2010). On the morpho-syntax of (anti-)causative verbs. In M. Rappaport-Hovav, E. Doron, & I. Sichel, Syntax, Lexical Semantics and Event Structure (pp. 177-203). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ASHER, N., & LASCARIDES, A. (2001). Metaphor in Discourse. In P. Bouillon, & F. Busa, The Language of Word Meaning (pp. 263-287). Cambridge: Cambrigde University Press. BOSQUE, I. (2004). REDES Diccionario combinatorio del español contemporáneo. Madrid: Ediciones SM. HALE, K., & KEYSER, S. (1993). On argument structure and the lexical expression of grammatical relations. In K. Hale, & S. Keyser, The View from Building 20: Essays in Linguistics in Honor of Sylvain Bromberger (pp. 53-110). Cambridge: MIT Press. HANKS, P. (2011). Lexical Analysis: Norms and Exploitations. LEVIN, B. (1993). English Verb Classes and Alternations: A Preliminary Investigation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. LEVIN, B., & RAPPAPORT HOVAV, M. (1995). Unaccusativity At the Syntax-Lexical Semantics Interface. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology. RAPPAPORT HOVAV, M., & LEVIN, B. (2002). Change of State Verbs: Implications for Theories of Argument Projection. Proceedings of the 28th Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, (pp. 269-280). Berkeley. RAPPAPORT HOVAV, M., & LEVIN, B. (1998). Building Verb Meanings. In M. Butt, & W. Geuder, The Projection of Arguments, Lexical and Compositional Factors (pp. 97-134). Stanford: CSLI Publications. RAPPAPORT-HOVAV, M., & LEVIN, B. (2011). Lexicon Uniformity and the Causative Alternation. En M. Everaert, M. Marelj, & T. Siloni, The Theta System: Argument Structure at the Interface. Oxford: Oxford University Press. REAL ACADEMIA ESPAÑOLA. (n.d.). Real Academia Española. Retrieved Junio 20, 2008 from Diccionario de la Lengua Española: http://www.rae.es/rae.html