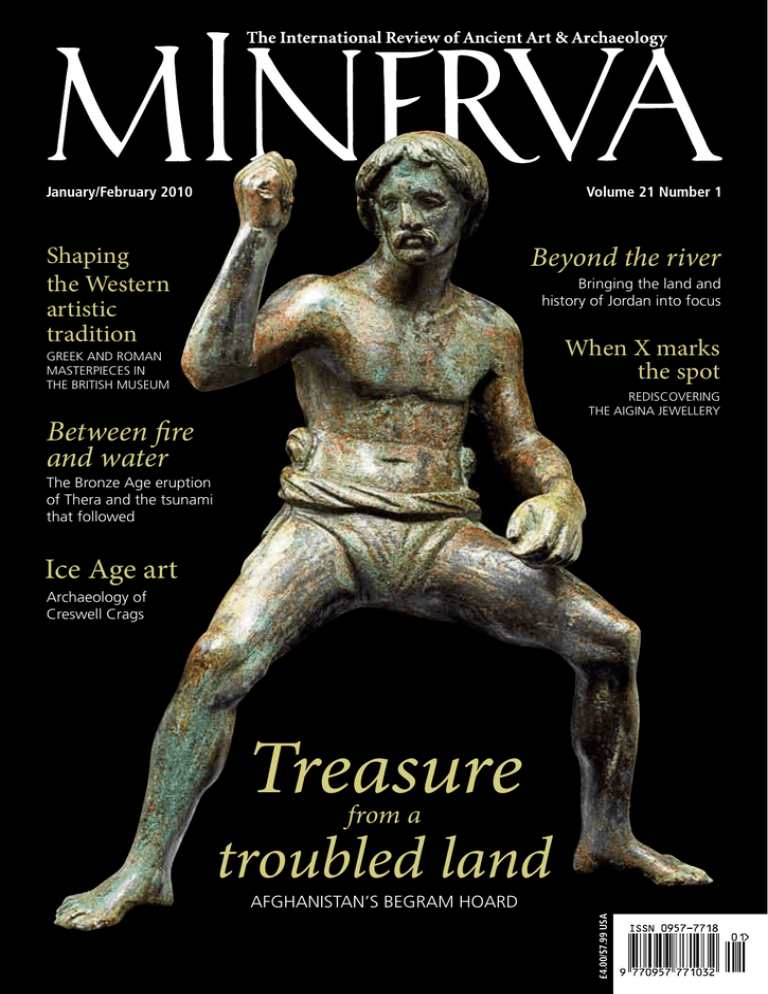

vol 21 (2010)

Anuncio