DOCUMENTO DE TRABAJO DE LA FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS

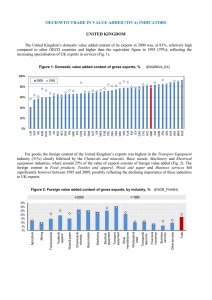

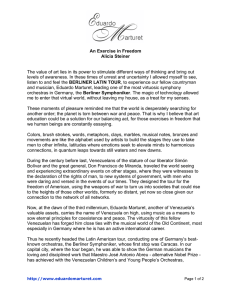

Anuncio