555314-16 bk Monteverdi EU

Anuncio

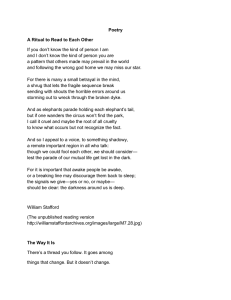

TRISTAN’S HARP Arthurian Medieval Music Capilla Antigua de Chinchilla • José Ferrero Tristan’s Harp Arthurian Medieval Music 1 Alfonso X el Sabio (1221-1284): O que a Santa Maria – Cantiga 35 4:04 2 Anonymous Italian (14th century): Lamento di Tristano – Contrafactum (Text: Tristant muste sonder danc by Heinrich von Veldeke, 1150-c.1190) 4:49 3 Anonymous English (13th century): “Dance of the forest of no return” – Stantipes I (Instrumental) 4 Thibaut de Champagne (1201-1253): Deus est ensi comme li pellicanz 5 Anonymous English (12th century): Redit aetas aurea 6 Richard I, Cœur-de-Lion (1157-1199): Ja nuls homs pres 7 Anonymous French (c.1190): Pange melos lacrimosum 8 Anonymous French (13th century): Quarte Estampie Royale (Instrumental) 9 Le Châtelain de Coucy (c.1165-1203): La douce voiz du louseignol sauvage 2:28 5:28 3:51 6:03 3:21 4:17 6:23 0 Anonymous English (13th century): “Dance of the forest of no return” – Stantipes II (Instrumental) ! Bernart de Ventadorn (c.1130-1200): Can vei la lauzeta @ Alfonso X el Sabio: Des quando Deus sa madre – Cantiga 419 (Instrumental) 1:25 7:31 2:41 # Anonymous English (13th century): “Dance of the forest of no return” – Stantipes III (Instrumental) $ Alfonso X el Sabio: Dereit’ é de ss’ end’ achar – Cantiga 108 1:59 6:56 Capilla Antigua de Chinchilla Luisa Maesso, Castanets 1, Voice 2 5-7 9 $, Tambourin à Cordes 3 8 0 # Juan Francisco Sanz, Darbuke 1 @ $, Tambour 3 5 7 8 0 #, Voice 4-7, Bendir 6, Drum 9, Riqq @ José Ferrero, Harp 1 4 6 9 ! @, Simphonie 2 3 5 7 8 #, Voice 5 6 ! $, Anglo-Saxon Lyre 0, Psaltery $ Ana María López-Pintor, Rabel 1-4 6 8-0 @-$, Fiddle 5 7 Sergio Alonso, Tenor Rabel 1 2 4 5 7 9 @ $, Tromba Marina 1 @, Viol 3 6 8 0 ! # Alfonso Sáez, Medieval Flute 1 3 6 8 9 @-$, Tenor Medieval Flute 2 !, Chalumeaux 4, Glastonbury Pipe 5 7, Organetto 5 0, Gaita $, Horn $ José Ferrero, Director 8.572784 2 Tristan’s Harp Arthurian Medieval Music “I know well how to play the harp and rote and how to sing in key” Folie Tristan (Oxford version) Ever since they first began to spread across Europe in the Middle Ages, the tales of King Arthur and his knights have inspired creativity in all spheres of artistic expression, music being no exception. At the same time as the literary works of Chrétien de Troyes or Geoffrey of Monmouth were appearing, bards and troubadours too were drawing on the tales for lyrical inspiration. By the thirteenth century, the songs of troubadours, trouvères and Minnesänger had brought the stories of Arthur, Merlin, Percival, Tristan and Iseult et al. (not to mention the Holy Grail) to audiences far and wide. This album takes a journey through the twelfth-, thirteenth- and fourteenthcentury Arthurian musical traditions of Germany, Spain, France and England. The chivalric feats, enchanted forests and love potions of the chronicles suited the courtly love aesthetic to perfection. It comes as no surprise, therefore, that music, adventure and love should go hand in hand, or that Tristan should be a skilled harpist who teaches Iseult to play. Music becomes an indispensable element in the development of the Arthurian legend. The so-called “Matter of Britain” also reached the Iberian Peninsula, travelling along the “Camino de Santiago” to inspire poetry in the Galician-Portuguese language. Tristan’s Harp opens with one of the Cantigas de Santa Maria (Canticles of the Virgin Mary) which were produced during the reign of Alfonso X, some of them written by the king himself, and which as a whole constitute the most significant song collection of medieval Spain. Cantiga No. 35, O que a Santa Maria (He who to the Virgin Mary) 1, like most of the poems, tells the story of a Marian miracle, but also mentions King Arthur, as does No. 419, Des quando Deus sa Madre (Since God his Mother) @. Merlin, meanwhile, appears in No. 108, Dereit’ é de ss’ end’ achar (It is right therefore) $, in which he 3 argues with a Jewish sage about the doctrine of Incarnation. Thibaut de Champagne, also known as Theobald I of Navarre and Theobald the Chansonnier, was born in Troyes in 1201 and died in Pamplona in 1253. He was a prolific writer and created works in a variety of genres, including the political song or serventois featured here, Deus est ensi comme li pellicans (God is like the pelican) 4 . This is thought to reflect the dispute that lasted from 1236 to 1239 between the Church, in the shape of its head, Pope Gregory IX, and the German emperor Frederick II, over where those preparing to fight in the Sixth Crusade should be sent (Palestine or Constantinople). It includes an allusion to the wisdom of Merlin, and grows in intensity as Thibaut accuses the Church of abusing its position. Redit aetas aurea (The age of gold returns) 5 is an anonymous English two-part conductus in the style of the Notre Dame School. It belongs to the Old St Andrews Music Book (W1) and was normally performed as a processional piece. Written for the coronation of Richard the Lionheart, it was also used for those of some of his successors. Richard himself wrote the song Ja nuls homs pres (No man imprisoned) 6 while he was being held prisoner in Dürnstein as part of his eventful journey home from the Third Crusade in 1192. Captured near Vienna by Leopold V, Duke of Austria, he was then handed over to the German emperor, Henry VI. Richard wrote this song in both the langue d’oc and langue d’oïl – the more frequently performed and better-known version is the latter, in the language of northern France (medieval French), and we have therefore chosen to perform it in the langue d’oc, or Occitan, on this album. The lyrics of this, perhaps one of the most beautiful songs of the entire medieval period, tell of his unhappiness at having to wait for his ransom to be paid. Pange melos lacrimosum (Compose a sorrowful song) 7 is another anonymous two-part conductus of the 8.572784 Notre Dame School. It appears to refer to the death in 1190 of the German emperor Frederick Barbarossa when he was on his way to fight alongside Richard in Palestine. Barbarossa, like Arthur, was to become the subject of numerous myths and legends. A common musical form in the Middle Ages was that of the contrafactum, in which a text was adapted to a piece of music that suited its metre, so that musicians simply needed to learn new words for tunes they knew well. We include here a text by Heinrich von Veldeke, Tristrant muste sonder danc (Tristran was involuntarily faithful) 2, set to the music of an anonymous fourteenthcentury Italian piece entitled Lamento di Tristano. A further mention of Tristan is to be found in Can vei la lauzeta (When I see the lark) !, one of the best-known songs of the troubadour repertory. Its author, Provençal poet and composer Bernart de Ventadorn, served at the court of Eleanor of Aquitaine (Richard the Lionheart’s mother) in England, then returned to Aquitaine – firstly to the court of Narbonne and then to that of Raymond V of Toulouse. On the latter’s death in 1194, Bernart became a monk at the Abbey of Dalon, where he later died. Trouvère Le Châtelain de Coucy compares himself to Tristan grieving for his lost love in his song La douce voiz du louseignol sauvage (The sweet voice of the wild nightingale) 9. A highly tragic tale grew up around Le Châtelain de Coucy, inspiring a number of books on the subject: legend had it that after his death, the poet’s heart was fed to his lover, the Dame de Fayel, by her jealous husband… The Stantipes (or Estampies) I, II and III 3 0 # are anonymous thirteenth-century English dances, to which we decided to add a subtitle befitting this album’s Arthurian slant. In common with other estampies, such as the well-known piece entitled Tre fontane (Three fountains), they can also be seen as abstract instrumental works. Our chosen subtitle, “Dances of the forest of no return”, is a nod to a reference in the Vulgate Cycle to the knights and ladies compelled to dance for ever in the “Forest Perdue”. José Ferrero English version: Susannah Howe Capilla Antigua de Chinchilla Founded in 2002 for the study and revival of early music, the Capilla Antigua de Chinchilla is directed by its founder, the tenor José Ferrero. The ensemble has participated in festivals and concerts throughout Spain, including the Hellín Early Music Festival, the 2005 Liétor Organ Festival and Festivals of the Early Music of Chinchilla in 2006 and 2007, and at the Musical October of Carthage in Tunisia in 2008. Recordings include music from the Cancionero of Alfonso X and the Sung Passion of Chinchilla, works by Ginés de Boluda, who served at the cathedrals of Cuenca and Toledo in the sixteenth century, with a third recording devoted to works by Rogier, Victoria, Morales and Guerrero, among others, performed with the historic organ of Liétor. In 2007 another recording was devoted to the medieval music of pilgrims and sephardim. Their most recent recording of sephardic music, Endechar: Lament for Spain, was released on Naxos 8.572443 in 2010: the music has been performed at major festivals throughout the world. 8.572784 4 Luisa Maesso The mezzo-soprano Luisa Maesso Martínez was born in Úbeda (Jaén) and studied at the Conservatorio de Madrid. She made her début at the Teatro de la Zarzuela in Madrid in 1994. She appears regularly with the Capilla Antigua de Chinchilla and collaborated with the Capilla and the Banchetto Musicale in 2006 in the revival of Johann Sebastiani’s St Matthew Passion under Pere Ros. She participated in the Naxos recording of Cavalli’s Gli amori di Apollo e Daphne under Alberto Zedda (8.660187-88). Juan Francisco Sanz The countertenor Juan Francisco Sanz was born in Albacete, where he began his musical studies, and from childhood he participated in choral singing. His technical training was with the tenor José Ferrero and he received help from the countertenor José Hernández Pastor. He had further vocal training with Robert Expert, Ana Luisa Chova, Lola Bosson and Carmen Subrido, among others. He directs the choir Concentus Torrejón y Velasco de Albacete and the choir of the Escuela Universitaria de Magisterio of Albacete. Ana María López-Pintor Born in Campo de Criptana (Ciudad Real), where she started her musical training, the violinist Ana María López-Pintor continued her studies in Ciudad Real and Alicante, where she obtained her Título Superior de Violín. She has a degree in music education from the University of Castilla-La Mancha. Since 2007 she has collaborated with the Capilla Antigua de Chinchilla, with which she recorded Io son un pellegrin. She is a member of the Albacete Orquesta Sinfónica, and professor of violin and chamber music at the Albacete Conservatorio Profesional de Música Tomás de Torrejón y Velasco. 5 8.572784 Sergio Alonso A native of Sigüenza (Guadalajara), Sergio Alonso studied at the conservatories of Guadalajara and Madrid, qualifying in harmony and violin. He also graduated in mathematics at the Madrid Universidad Complutense and in musicology at the Universidad de la Rioja. He is professor of harmony at the Albacete Conservatorio Tomás de Torrejón y Velasco and has been associate professor at the Albacete Faculty of Education. As a violinist he appears with the Orquesta de Albacete and also with the Capilla Antigua de Chinchilla, with which he plays various instruments. Alfonso Sáez Docón Born in Liétor (Albacete), Alfonso Sáez Docón began his musical studies at the Albacete Conservatorio, with courses in piano and saxophone. He went on to study the organ at the Valencia Conservatorio Superior de Música under Vicente Ros, continuing at the Salamanca Conservatorio with Luis Dalda and finally with Javier Artigas in Murcia. He serves as organist at the Church of St James the Apostle and is a member of the Capilla Antigua de Chinchilla, with which he has made various recordings. He is professor of organ at the Murcia Conservatorio Profesional de Música. José Ferrero Born in Albacete, the tenor José Ferrero studied singing in Valencia with Ana Luisa Chova and has appeared as a soloist with distinguished conductors and colleagues, performing in Europe’s principal theatres and festivals. His interest in early music led to the foundation in 2002 of the ensemble Capilla Antigua de Chinchilla, also recorded on Endechar (Naxos 8.572443). He participated in the Naxos recording of Cavalli’s opera Gli amori d’Apollo e di Dafne under the direction of Alberto Zedda (8.660187-88). Photographs by Juan Rodríguez 8.572784 6 El arpa de Tristán Música medieval artúrica “Sé tocar el arpa, la rota y la cítara y cantar como los pájaros.” Tristán (Oxford) Las leyendas artúricas han sido fuente de inspiración para todo tipo de artes desde su aparición en la Edad Media y la música no es una excepción. Casi paralelamente a la creación de las obras de Chrétien de Troyes o de Geoffrey de Monmouth, los trovadores y bardos comenzaron a inspirarse en las leyendas artúricas para la creación de sus obras. Temas como el Rey Arturo, el Grial, Merlin, Perceval, o Tristán e Isolda ya son famosos en el siglo XIII y se ponen en boca de toda la gente, sea de la clase social que sea, gracias a las creaciones de trovadores, troveros y Minnesänger. Este album hace un recorrido a través de las tradiciones musicales artúricas de los siglos XII, XIII y XIV de Alemania, España, Francia e Inglaterra que se inspira en la literatura artúrica. En la estética del Amor Cortés, las epopeyas caballerescas, los bosques oscuros y perdidos, los filtros amorosos de las leyendas artúricas encajan perfectamente. Por ello no nos extraña que la música, la aventura y el amor vayan unidos y que Tristán sea un gran arpista que enseñe a Isolda a tocarla. La música es un elemento que se hace indispensable en el desarrollo de los acontecimientos artúricos. El Camino de Santiago supuso la vía de acceso de las leyendas artúricas en la Península Ibérica, al igual que de intercambio cultural entre el norte y sur de Europa. La música de nuestro disco El arpa de Tristán comienza con una de las Cantigas de Santa María de Alfonso X, el Sabio, que reflejan la influencia de la Materia de Bretaña. En la Cantiga 35, O que a Santa Maria 1, aparece el nombre del Rey Arturo mezclado con el milagro de la Virgen María. En la Cantiga 419, Des quando Deus sa madre @, aparece otra vez el nombre del Rey Arturo en la narración, mientras que el protagonista de la Cantiga 108, 7 Dereit’ é de ss’ end’ achar $, es el mago Merlín, que recrimina la actitud contra la Virgen de un judío. Thibaut de Champagne, también conocido como Teobaldo I de Navarra o Teobaldo el “chansonnier”, nació en Troyes en 1201 y murió en Pamplona en 1253. Fue trovero muy reconocido por sus poesías políticas. Deus est ensi comme li pellicans 4 es una canción, un serventois, en protesta contra la Iglesia y el Papa Gregorio IX por alargar la Sexta Cruzada (1236-1239). En esta canción Merlín y su brujería están presentes junto a la Iglesia. Es una canción que va creciendo en intensidad conforme va recriminando a la iglesia sus extralimitaciones. Redit aetas aurea 5 es un conductus anónimo inglés a dos voces al estilo de la Escuela de Notre Dame. Pertenece al Old St Andrews Music Book (W1) y era normalmente usado en las procesiones. Compuesto para la coronación de Ricardo Corazón de León como Rey de Inglaterra, fue usado posteriormente para la coronación de otros reyes Plantagenet. Ricardo Corazón de León compuso su canción Ja nuls hom pres 6 estando preso en Dürnstein tras un accidentado regreso de la Tercera Cruzada en 1192. Después de ser apresado por Leopoldo V, Conde de Austria, cerca de Viena, fue llevado a presencia del emperador de Alemania, Enrique VI. Esta canción la escribió en langue d’oc y en langue d’oïl, pero la versión más interpretada y conocida es la de langue d’oïl, es decir la del norte de Francia o francés medieval, por eso hemos optado por interpretar en nuestro CD la de langue d’oc u occitano. En esta canción se lamenta de como ninguno de sus reinos ni aliados viene en su ayuda. Quizá estamos frente a una de las canciones más bellas compuestas en el medievo. Pange melos lacrimosum 7 es otro conductus a dos voces de compositor anónimo de la Escuela de Notre Dame; parece referirse a la muerte del emperador Federico Barbarroja cuando iba al encuentro de Ricardo Corazón de León en 1190. En Alemania Barbarroja, antiguo Rey del Sacro Imperio Romano-Germánico, tiene un entorno de leyenda parecido al del Rey Arturo. 8.572784 De Heinrich von Veldeke podremos escuchar un contrafactum hecho con su texto Tristrant muste sonder danc 2 y la música de la pieza instrumental anónima italiana del siglo XIV Lamento di Tristano. Esta fórmula del contrafactum, es decir coger un texto y adaptarlo a una música que le fuera bien métricamente, era muy común en la Edad Media y los músicos medievales lo hacían hábilmente, simplemente memorizando los nuevos textos a las ya sabidas melodías. Bernart de Ventadorn, trovador provenzal, estuvo unido un tiempo a Leonor de Aquitania (madre de Ricardo Corazón de León) y su corte, pero regresó a Aquitania a la corte de Narbona y finalmente a la corte de Raimundo V de Toulouse. Al morir éste en 1194, Bernart se hizo monje en la abadía de Dalón, donde murió. Su canción Can vei la lauzeta ! es una las mas celebradas del repertorio trovadoresco. En ella aparece de nuevo el nombre de Tristán. El trovero Le Châtelain de Coucy se compara con Tristán, lamentando un amor perdido, en su canción La douce voiz du louseignol sauvage 9. La historia de la vida de Le Châtelain de Coucy es una de las más tristes y conocidas del medievo. La leyenda de que el marido celoso de la Señora de Fayel le hizo comer el corazón de su amante, nuestro trovero, después de haber descubierto el romance entre ambos, se hizo muy famosa, llegando a escribirse varios libros en torno a esta historia. Las Stantipes I, II y III 3 0 # son danzas anónimas inglesas del siglo XIII, a las cuales les hemos querido dar un subtítulo adecuado al ambiente artúrico del disco. Al igual que otras estampies como Tre Fontane pueden tener una interpretación abstracta; eso es lo que hemos querido hacer aquí con las Stantipes, por tanto los hemos llamado Danzas del bosque sin retorno. Elegimos este nombre porque el que entra en el bosque y escucha la música no puede parar de bailar, así aparece en la Suite Merlín (Vulgata). José Ferrero 8.572784 8 Also available E A R L Y 8.572443 8.553617 8.554837 8.557637 M U S I C NAXOS NAXOS 8.572784 TRISTAN’S HARP Playing Time 61:16 Arthurian Medieval Music 4:04 4:49 2:28 4:17 6:23 1:25 7:31 2:41 8.572784 & 훿 2012 Naxos Rights International Ltd. Booklet notes in English • Comentarios en español 8.572784 A detailed list of tracks and artists can be found on page 2 of the booklet The sung texts and English translations can be accessed at www.naxos.com/libretti/572784.htm Recorded at Iglesia de San Antón, Chinchilla de Montearagón, Albacete, Spain, from 29th August to 3rd September, 2011 • Producer: José Ferrero • Engineer: Pascual Lorenzo González Editors: Pascual Lorenzo González and José Ferrero • Booklet notes: José Ferrero Publishers: La música de las cantigas de Santa María del Rey Alfonso X el Sabio (Higinio Anglés, Barcelona, 1943 (Diputación Provincial)) (tracks 1, 2, 14); Trouvères et Troubadours (Pierre Aubry, Paris; Félix Alcan, Editeur, 1909) (tracks 3-13) Cover: Tristan sings a love song for Isolde, King Marke appears from Le Livre de Tristan et la reine Yseult de Cornouaille et le graal (Illumination, French, 14th century) (Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris / akg-images) Made in Germany Capilla Antigua de Chinchilla • José Ferrero, Director www.naxos.com 1:59 6:56 3 5:28 3:51 6:03 3:21 Quarte Estampie Royale La douce voiz du louseignol sauvage 0 Dance of the forest of no return ! Can vei la lauzeta @ Des quando Deus sa madre # Dance of the forest of no return $ Dereit’ é de ss’ end’ achar 8 9 47313 27847 O que a Santa Maria Tristrant muste sonder danc 3 Dance of the forest of no return 4 Deus est ensi comme li pellicanz 5 Redit aetas aurea 6 Ja nuls homs pres 7 Pange melos lacrimosum 1 2 TRISTAN’S HARP: Arthurian Medieval Music DDD 7 TRISTAN’S HARP: Arthurian Medieval Music The feats of King Arthur and his Knights have inspired artistic creation in many art forms. In this disc we hear how troubadours spread their stories and we journey through twelfth-, thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Europe to encounter the Arthurian musical traditions of Germany, Spain, France and England. Full of allusions to legend, and also to contemporary events, the songs are masterpieces of their time. The composers include Alonso X el Sabio of Spain and Richard the Lionheart, whose Je nulls homs priz is one of the most beautiful of all medieval songs.