la alternancia haber de/tener que + infinitivo

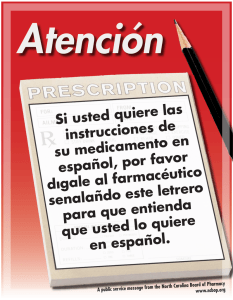

Anuncio