Customs issues falling under INTA`s new remit

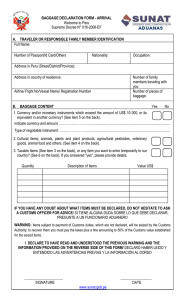

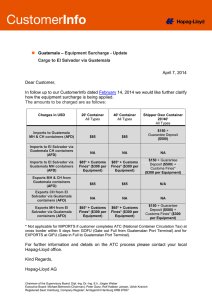

Anuncio