Professor Ana Celia Zentella

Anuncio

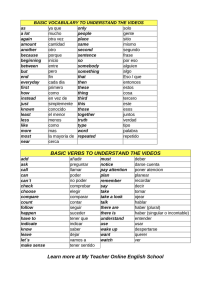

Professor Ana Celia Zentella Professor Emerita UCSD, Ethnic Studies azentella@ucsd.edu Mapa 1: La frontera mexicano‐estadounidense Fuente: h8p: //www.epa.gov/usmexicoborder/ef‐maps.htm SAN DIEGO vs. TIJUANA SAN DIEGO TIJUANA PopulaNon 1.4 million 1.5 million Per Capita Income $33,883 $9,812 Median Home Price $410,000 $35,000.3 SAN DIEGO County: Pop. 3 Million 11.7% live below the federal poverty level TIJUANA: 34.5% in poverty: insufficient income for food, educa:on, health, clothing, shoes, housing, transporta:on . Interna:onal Community Founda:on's study "Blurred Borders: Trans‐Boundary Impacts and Solu:ons in the San Diego‐Tijuana Border Region" edited by Naoko Kada and Richard Kiy (March 2004): hZp://www.icfdn.org/publica:ons/blurredborders/39sdtjataglance.htm Tijuana: "Tijuana is Mexico’s fastest-growing city (a population of 750,000 in 1990, 1.2 million in 2000 and projected to be 2.2 million by 2010). --60 million people cross the border there each year” ‐‐ “It’s Hot. It’s Hip. It’s Tijuana?” by WILLIAM L. HAMILTON,. NYTIMES, August 25, 2006. Hispanics in San Diego: • 44% of Hispanic full-time workers earn less than the selfsufficiency income of $25,950 per year. . Nearly half (46%) of full-time Hispanic workers are employed in the top five lowest wage occupations. Familias pobres se enfrentan a la falta de oportunidades para mejorar su ingreso: http://www.oem.com.mx/elsoldetijuana/notas/n1083326.htm Earnings, Poverty and Income Inequality in San Diego County: Analysis of regional data from the US Census Bureau; 2006 American Community Survey: hZp://209.85.173.132/search?q=cache:s4RnmxWupZIJ:www.communitybenefits.org/downloads/Earnings%2520Poverty%2520and%2520Income%2520Inequality%2520in%2520San %2520Diego%2520County.pdf+poverty+hispanics+san+diego&cd=5&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=us&client=safari E-1 Population Estimates for Cities, Counties and the State with Annual Percent Change — January 1, 2008 and 2009". California Department of Finance. 2009-05. Retrieved on 2009-05-02. http://wiki.answers.com/Q/What_is_the_population_of_Tijuana Poverty, Income and Employment For Hispanics in San Diego County: http://www.onlinecpi.org/article.php?list=type&type=80 TIJUANA‐SAN DIEGO BORDER CHECKPOINT TIJUANA‐SAN DIEGO BORDER FENCE More than 2.5 million people cross the Tijuana‐ San Diego border every month; some 30,000 people cross daily on foot, and 45% of those are students. Many take the trolley to their private or public school in San Diego. “México‐Estados Unidos: VIVIR EN LA FRONTERA”, Por: Patricia Ruvalcaba (Revista MILENIO Semanal): hZp://lists.econ.utah.edu/pipermail/reconquista‐popular/2005‐ 9,500‐15,000 students cross daily for school ‐‐ "Blurred Borders: Trans‐Boundary Impacts and Solu:ons in the San Diego‐ Tijuana Border Region" edited by Naoko Kada and Richard Kiy (March 2004). May 21, 2009: three students (15‐17 yrs old) with local H.S. IDs were stopped at the Old Town trolley sta:on and deported to Tijuana for lack of documenta:on. THE REPRODUCTION OF LINGUISTIC AND EDUCATIONAL INEQUALITY Do the linguis:c abili:es, prac:ces, and avtudes of transfronterizo students reinforce or challenge: 1) classic no:ons of the “ideal bilingual” who … “switches from one language to the other according to the appropriate changes in the speech situa:on (interlocutors, topic, etc.), but not in unchanged speech situa:ons, and certainly not within a single sentence” (Weinreich 1968:73). 2) “the dominant nega:ve narra:ve about language, culture, iden:ty, and academic failure [of Mexicans on the border]” (Venegas‐García & Romo 2005:1)? TRANSFRONTERIZO COLLEGE STUDENTS Gen. Age Born YXing Sch: F 21 US 14 B F 24 US 12 PR F 29 MEX 12 B F 23 EUR 4 PR F 28 US 8B F 30 US 14 PR F 36 US 4 PU F 31 US 12 B F 28 US 4 PR F 29 MEX 12 PR F 24 US 16 B F 22 US 12 PR F 22 US 12 PR F 26 US 4 PR F 28 US 12 PR F 29 US 16 B F 24 US 4 PU F 26 MEX 12 B F 34 USA 12 PR F 30 USA 12 B F 27 US 16 B Gen. Age Born YXing Sch: F 24 US 17 B F 21 US 7B F 22 US 14 B F 27 MEX 3 PR F 22 US 14 PR F 30 MEX 4 PR F 26 US 7B F 21 US 12 B F 21 US 4 PU F 22 US 7 PR F 21 US 7B F 20 US 6B F 22 US 11 B F 19 US 10 PU F 22 US 2B F 19 MEX 7 PU F 25 US 10 PU F 14 US 2B F 19 US 6 PU F 22 MEX 5B F 15 MEX 5B Gen. Age Born YXing Sch: F 17 MEX 5 PU F 17 MEX 1 PU M 25 MEX 12 PR M 26 US 14 B M 30 US 14 B M 16 US 5 PR M 26 MEX 8B M 26 MEX 6 PR M 20 MEX 3B M 18 MEX 1 PU M 19 MEX 1 PU M 22 MEX 4 PU M 22 US 12 B M 17 US 4 PU M 17 MEX 1 PU M 29 MEX 11 B M 17 US 3B M 26 US 12 B M 25 US 16 PR M 24 US 12 B M 26 MEX 3 PR Gen. Age Born YXing Sch: M 25 MEX 4 PR M 26 US 12 B M 23 US 4 PR M 26 US 16 B M 29 US 12 PR M 26 US 3B M 25 MEX 12 PR M 22 MEX 4 PR M 35 MEX 4 PU M 23 US 4B M 25 US 4 PR M 26 MEX 12 PR M 29 US 12 PR M 29 MEX 12 PR M 26 MEX 8 PR M 23 MEX 12 B PR= private school PU= public school B= both Overview of Transfronterizo College Students (n=79) • Birthplace: 35.4% Mex 63.3% US • Age: F= 17- 36 yrs, avg.=23yrs – • • • M= 17-35 yrs, avg.=24yrs Gender: 54% F, 46% M Years Crossing: 1-17 years, avg.= 8.4 yrs Schooling: – – – • 1.3% Eur Private= 35% Public= 17% Both= 48% Residence: 51% TJ, 49% SD "El letrerito q veo todos los días, solo una línea q divide vidas“ [The li8le sign I see every day, just a line that divides lives’; myspace webpage, fem 23 yrs old ‘] I. What role does the border play in the “imagined community/ ies” (Anderson 1991) of transfronterizo youth? Q : How powerful, in your mind, is the border? [choose from among 4 lines of intensity] a) ……………………………………………………………………………………………… b) ____________________________________________________________________ c) d) Fem#8: “ D. It’s just soo powerful. I mean I crossed that border and that was the line that divided my life!.... . maybe that was the line that divided being somebody or not.“ [19 yrs old, born & raised in TJ, crossed 10th ‐12th grades for public HS, UCSD student] Fem#7: “Para mi es la a) porque es permeable. En mi caso, pero te apuesto para el que se murió hace rato cruzando la frontera va a ser esta. “ [For me it’s a) because it’s permeable. In my case, but I bet you that for the person who died crossing the border a while back it would be this one [poin:ng to d]’ [25 yrs old, born & raised in TJ, crossed to public schools 5th, 6th, 8th, 9th, 10th‐12th, & UCSD] A. B. C. – – EXCEPT: “Language and communica:on are cri:cal aspects of the produc:on of a wide variety of iden::es expressed at many levels of social organiza:on” (Kroskrity, 2001:106). “the illusion of linguis:c communism” (Bourdieu, 1991:43). Race has been remapped from biology onto language (Urciuoli 2001) BOTH RACE AND LANGUAGE ARE CONSIDERED HIERARCHICAL: SUPERIOR AND INFERIOR VARIETIES POLLUTING: BOUNDARIES MUST BE ENFORCED BIOLOGY CANNOT BE CHANGED, BUT LANGUAGE CAN AND SHOULD BE 1. 2. "…eran de descendencia mexicana pero ya muy aculturados, defini?vamente sí puro inglés o sea ni sus nombres los querían decir bien en español.” [‘they were of Mexican origin but already very acculturated; definitely English only and I mean they didn’t even want to say their names correctly in Spanish.’] 3. “el español lo hablan como ?po inglés pero ?enen el nopal en la cara“ [‘they talk Spanish as if it were English despite the cactus on their face’ [obviously Mexican looks]] 4. “Straight out Mexican, no. I would say Mexican‐American. It varies so much if they don’t know the language. I don’t think they can claim themselves as Mexican.” 5. “...la imagen que tenemos los mexicanos no es muy buena que digamos así como te asocian con puras delincuencias, y … a veces es diGcil demostrar que tú no eres uno de esos mexicanos… por eso mucha gente prefiere ser así como "Ay no no, yo no hablo español" para que digan "Ah este es uno de los otros mexicanos, de los mexicanos que es más americano que mexicano pues, no es de esos mexicanos cholos y de ese ?po de mexicanos.“ [‘the view of Mexicans is not so good shall we say so they associate us with pure delinquency and some?me it’s hard to prove that you’re not one of those Mexicans… that’s why many people prefer to be like “Oh no no, I don’t speak Spanish”, so that they can say “Oh, this is one of the other Mexicans, the Mexicans who are more American than they are Mexican, not one of those gang member Mexicans or that kind of Mexicans.’] IV English as cultural and symbolic capital: legality, respect, race, intelligence, envy 1. “I did it once because I forgot my mica [green card]. (What did you do?) I said “US ci:zen”, (laughter) but just once. (How good does your English have to be?) Just good enough, I mean, just don’t trip. Don’t sound like "JES, U.S. city‐sen” [with Spanish accent) (laughter) (Is your English enough or do you have to look a certain way?) Well, if you look like very very Mexican , like if you have like, like a sombrero, or something, I mean they're not going to believe you …with a virgen tatuaje [‘tatoo]“(laughter) [19 yrs old, born & raised in TJ, crossed 10th ‐12th grades in public HS, UCSD student] 2. “Honestly right now [a€er 9/11]…I think the only way you can get across the border with no ID is if you are the stereotype of a white kid.” (F, 22, b. US, 2yrs crossing to college) 3. Speaking English in Tijuana A. “En México si hablas inglés, te dicen como que. ‘Ay tú qué te crees, qué ridículo, o qué esNrado, qué creído’, entonces pues no lo haces.” [In Mexico if you speak English they tell you like,” Oh who do you think you are, how ridiculous, what a stuck‐up, what a show off, so you don’t do it.’] [Male#9, 20, b. Mex, crossed 3yrs to public HS, UCSD student] B. [Los que hablan inglés en Tijuana] “ …están presumiendo que vienen de este lado [US], que según ellos que están en un lugar económico mejor que los de México, simplemente por el hecho que están en Estados Unidos y todo eso lo ejemplifican al hablar en inglés.” [Those who talk Engish in TJ] “they’re showing off that they come from this side (USA), that according to them they’re be8er off economically than those who live in Mexico, just because they’re in the US and they represent all that by talking in English.’] [fem#7, 25 yrs old, born & raised in TJ, crossed to public schools 5th, 6th, 8th, 9th, 10th‐12th, & UCSD] 4. ENGLISH Discourse Style: LIKE (n= 0‐171) “They have this bad image, like when, well she was my roommate uhm and she’s like I was talking about, I was talking to my friend about my grandpa cause he was white like skin, with blue eyes, and she was like "Oh, was he Mexican?" and I’m like "Yeah he was like Mexican from like central Mexico." She's like "Oh I never knew that Mexicans could be white like, could have white skin" I’m like "what?!!!!" She's like "Yeah aren’t Mexicans like brown, short, and like bald and like ta8ooed and I’m like "No!!!! " I mean that was only in like one movie, what are you talking about? She’s like "Ahh I thought you guys were all like that" and "I’m like no, my mom is like super white, she has like almost green eyes, what the hell are you talking about?!" She’s like "Ah I thought all Mexicans are like that like brown and like brown hair, bald and old, and bald and short" and I’m like "What the heck?!!! No!!" And its because of that because like if you see the movies, like I don’t know, I don’t know‐‐movies about cholos, and they’re all Mexicans and they're all like "Yeah vato”, and … and people think we're like that, like all of us, and its not true. So they're like the bad stereotype of the Mexicans.” [fem, 19 yrs old, born & raised in Tijuana, crossed 10th ‐12th grades in public HS, UCSD student, like =124/3,378 = 3.7% ; osea =236/15,080= 1.6%] 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. “EL ser bilingüe es… que sabes los dos idiomas bien … es tener cultura.” [“To be bilingual is.. that you know both languages well… it’s being cultured.’] [re Spanglish] “la mayoria de mexicanos que yo conozco osea lo criNcamos mucho, se nos hace algo ridículo no? …arruinas los dos idiomas…“ [‘the majority of the Mexicans that I know I mean we criNcize it a lot, it seems ridiculous to us, right? … you’re ruining two languages.’] “Los pochos se juntaban con algún mexicano y así pero casi eran la mayoría puros mochos. Hablaban Spanglish a todo poder.” [The pochos would hang out with some Mexicans and like that but they were almost always pure mochos. They spoke Spanglish non stop.’] “Pocho for me means… doesn’t know English and doesn’t know Spanish, doesn’t know both languages and doesn’t know both of the cultures, kind of like a state of limbo, is [sic] lost. He idenNfies himself as one thing or another, but really he is nowhere really, he is in a state of limbo, he can’t speak to you about either American or Mexican history and culture.” Transfronterizos work harder than both Tijuas and Mexican Americans: “No especiales así de superiores pero, de cierta forma así como macheteadores pues, así como pues le chingamos más, no es así de que "Ay me levanto a la hora que se me dé la gana,” osea “si entro a las diez a la escuela me levanto a las nueve" osea yo si entraba a las siete me tenia que levantar a las cuatro, osea era cosa así de que… era mas chinga pues, asi como o, y osea tuve que aprender otro idioma.” [Not special in the sense of being superior, but in a certain way like more gunners, like we work harder , not like “Oh I get up whenever I feel like it, I mean if I start school at ten I get up at nine” I mean if I started at 7 I had to get up at 4, I mean it was like – I was more driven like and I mean I had to learn another language.”] 1. Almost all transfronterizos have been called ‘pocho/a” at some point. 2. Pochos “are trying hard to speak in Spanish and they want to communicate so they are making an effort to speak in Spanish even if they do not speak it well.” 3. “El spanglish, a mi no se me hace como una decadencia del español, ni una vergüenza , no para nada, es que es un contexto diferente….si vives en frontera no se puede evitar, yo creo que tendrías que luchar mucho en contra de eso, y al mismo Nempo estarías negando una dinámica que se da sólo en frontera, que es hablar así, y todo mundo lo habla y se te sale.“ [I don’t consider Spanglish a decadent Spanish , or shameful, not at all, it’s a different context.. ..if you live on the border it’s unavoidable, I think you’d have to struggle a lot against it, and at the same Nme you’d be denying a dynamic that occurs only on the border, which is talking like that, and everybody speaks it and it comes out. “] 4. “ Un amigo que creció y todo en el DF [decía] que el español se estaba contaminando… así bien extremista... Pero pues todo eso Nene que ver con la visión del centro, de la periferia, todo lo que es frontera y la falta de integración a la idenNdad nacional.” [A friend who was raised in the capital of Mexico used to say that Spanish was being contaminated.. like real extremist… . But then all that has to do with the center’s view of the periphery, everything that is the border and the lack of integraNon to the naNonal idenNty.” A. transfronterizo cultural capital “Those who are mulN‐lingual, have strong idenNNes, and are well educated have expanded employment possibiliNes, consumer choices, and more flexibility in their lives. Those who do not are at a disNnct disadvantage” (Venegas‐García & Romo 2005:3). B. The commodificaNon of bilingualism as two monolinguals joined at the tongue …because of the nature of the new economy, the ability to cross boundaries is important….what is valued is a mulNlingualism as a set of parallel monolingualisms, not a hybrid system.... This [new bilingual] elite builds a posiNon which marginalizes both those bilinguals whose linguisNc resources do not conform to the new norms, and those who are, simply, monolingual.” (Heller 1999:5). C. • • Changes in the linguisNc and socio‐poliNcal landscape have translated into different aƒtudes and a stronger linguisNc marketplace for Spanish. Although the Hispanophobia that characterizes the U.S. is sNll felt, the expansion of domains of use of Spanish to the more valued public sphere is challenging the sNgma a8ached to Spanish as a minority language. For middle class professionals at the border, there are opportuniNes to use their bilingual talents, and their knowledge of two cultures, as well as of two businesses and legal systems ( Achugar, 2008:7). An anthro‐poliNcal linguisNc perspecNve as the basis for a transformaNve pedagogy (Zentella, 1995, 2005): 1‐ values non standard dialects and code switching vs. elite definiNons of bilingualism 2‐ challenges the symbolic dominaNon of English and its ‘naturalized’ connecNon with Anglo Americans, and the link between being Mexican and speaking ‘pure’ Spanish 3‐ rejects ideologies, processes, and structural inequaliNes that produce rigid linguisNc, cultural, and naNonal boundaries, recognizing instead that “different types of idenNty are neither exclusive nor singular” (Kroskrity 2001:107). ‐‐ Por ejemplo, si yo estoy hablando ahorita y te trato de decir algo en español pero no me sale, I would have to say it in English porque that way it'll be easier, you know what I mean? Y a veces I tend to do that all the time, por ejemplo, like I would talk Spanglish, I would speak Spanglish. ‘for example if I’m talking right now and I try to say something in Spanish but I can’t get it out’ ‘because’ ‘and sometimes’ ‘for example’ - Interviewer: Y sí lo haces? ‘And do you do that?’ - Yes I would do that all the time with my friends, I would. Si lo ‘I do do it. Not all the time but the majority yes’ hago. No siempre pero la mayoria de las veces si, it would be like this. Like I would say something in Spanish and then ‘and I start to talk like oh you know y empiezo a Spanish. Like a whole hablar español. Como que una sentence in English and frase completa en inglés y luego then bang in Spanish, “beans”, or totally in pumm en español, “frijoles” o totalmente en español y pummm Spanish and bang’ you know what I mean? Asi. ‘like that’ And I don’t know if it's weird but it's just the way, yo pienso que es una dinámica ya de vivir aqui en la frontera de que se te sale el inglés o se te sale el español. Para mí no es difícil, la verdad es que yo pienso que ya te apr… you get used to it, so it’s like I don’t know it’s not even hard for me to you know like I'm talking to you in English then in Spanish pummm, no se. ‘I think it’s already a dynamic of living on the border that English comes out or Spanish comes out. For me it’s not difficult, the truth is that I think that you…’ ‘bang, I donno’ Y a veces cuando estoy en mi casa, mi hermana o mi hermano they would hear my conversation they’re like, “How can you do that, how can you talk in Spanish and then change all of a sudden like to English or me talking in English and then like "O sí luego la otra vez” este there was this girl you know and I couldn’t [sic] know how to talk to her *like asi like we would do that and she was like "Ay que...". ‘And sometimes when I’m at home, my sister or brother’ ‘Oh yes then the other time um’ ‘that’ ‘Oh that…’ Yo pienso que es como el siguiente paso *es como like. You know how I do that right now, "es como like" (laughter), it’s something you don’t even realize like you talk in English and Spanglish you know. Hay mucha gente piensa que es como una mutilación del lenguaje pero para mí no es así, para mí es como un tipo de metamorfosis que le pasa al lenguaje. ‘I think it’s like the next step it’s like LIKE’ ‘it’s like LIKE’ ‘A lot of people think that it’s a mutilation of the language but not me, for me it’s like a kind of metamorphosis’ Rompes ya la monotonía de que solamente el americano güero este blonde hair, blue eyes only speaks English or the Mexican dark skin, dark- only speaks Spanish pero it’s not like that, por ejemplo tienes yeah the typical American you know who is also fluent in Spanish y tienes por ejemplo a la persona de méxico que he looks like native he looks *like como Benito Juarez, ‘You break the monotony that only the blond American um’ ‘but’ ‘for example you have’ ‘and you have for example the person from Mexico that’ ‘LIKE like’ … que él era moreno chaparrito, like he would be fluent in English, you know, like ya no hay , yo pienso que ya no hay división de razas, yo pienso que quedan los estereotipos pero yo pienso que la combinación de razas yaaa.. yo pienso que ya there’s only gonna be one race. ‘who was dark and short’ ‘there are no longer, I think there’s no more division of races, I think that the stereotypes remain but I think that the combination of races .. I think that now’ -- Male 22yrs old.b. in MX a) border line Elem in TJ, 4 yrs crossing: H.S. in SD & City College student Achugar, Mariana. “Counter‐hegemonic language pracNces and ideologies: CreaNng a new space and value for Spanish in Southwest Texas.” Spanish in Context 5:1 (2008), 1‐19. Anderson, B. 1983. Imagined communi?es: Reflec?ons on the origin and spread of na?onalism. London: Verso. Bourdieu, P. (1991). The producNon and reproducNon of legiNmate language. In J.B. Thompson (Ed.), Language and symbolic power (pp. 43‐65). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. Heller, M. 1999. Linguis?c Minori?es and Modernity: A Sociolinguis?c Ethnography. NY& London: Longman. Kroskrity, P. 2001. IdenNty. In A. DuranN, ed. Key Terms in Language and Culture. Blackwell, 106‐9. Urciuoli, B. 2001. “The Complex Diversity of Languages in the US.” Cultural Diversity in the United States: A CriNcal Reader. Ed. Ida Susser and Thomas Carl. Malden: Blackwell Press. Venegas‐García & Romo 2005. Working Paper for Border Pedagogy Conference, USD, Oct. Zentella, A.C.. 1995. The ‘chiquita‐ficaNon’ of U.S. LaNnos and their languages, or Why we need an anthro‐poliNcal linguisNcs. SALSA III: the Proceedings of the Symposium about Language and Society at Aus?n. AusNn, TX: Department of LinguisNcs.1‐18. 1995. ________(Ed.) 2005. Building on Strength: Language and Literacy in La?no Families and Communi?es. Teachers College Press.