2011 Labour Overview. Latin America and the Caribbean. pdf

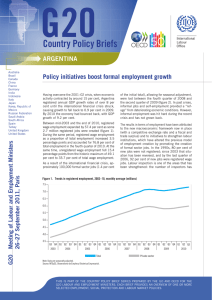

Anuncio