feeding broiler chicken with diets containing whole cassava root

Anuncio

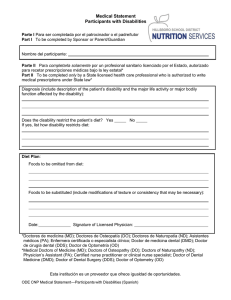

FEEDING BROILER CHICKEN WITH DIETS CONTAINING WHOLE CASSAVA ROOT MEAL FERMENTED WITH RUMEN FILTRATE ALIMENTACIÓN DE POLLOS CON DIETAS A BASE DE HARINA INTEGRAL DE RAÍZ DE YUCA, FERMENTADA CON FILTRADO RUMINAL Adeyemi, O.A.1, D. Eruvbetine2, T. Oguntona2, M. Dipeolu3 and J.A. Agunbiade1 Department of Animal Production. College of Agricultural Sciences. Olabisi Onabanjo University. Yewa Campus. P.M.B. 0012 Ayetoro. Ogun State. Nigeria. olajideadeyemi@yahoo.com 2 Department of Animal Nutrition. College of Animal and Livestock Production. University of Agriculture. P.M.B. 2240 Abeokuta. Ogun State. Nigeria. 3 College of Veterinary Medicine. University of Agriculture. P.M.B. 2240 Abeokuta. Ogun State. Nigeria. 1 ADDITIONAL KEYWORDS PALABRAS Manihot esculenta. Growing. Nutrient retention. Manihot esculenta. Crecimiento. Retención de nutrientes. CLAVE ADICIONALES SUMMARY 234 two week-old broilers, that were floor bred, were distributed into 18 groups of 13 birds each after balancing for live weights, randomly allocated to six dietary treatments in which 0, 12.5 and 25% of maize was replaced on a weight for weight basis with cassava enhanced with dried cage layer waste and fermented with rumen filtrate (CCLW). Each inclusion level was fed as mash and pellet form for duration of 6 weeks. The experiment was carried out as a 2x3 factorial design. A nutrient retention trial was carried out in the last week of the trial. Increasing the level of CCLW significantly reduced average daily weight gain (ADG) and average final weight (AFW) when fed in mash form (p<0.01). The retention of crude protein (CP), crude fibre (CF) and ether extract (EE) were depressed significantly (p<0.01) with increasing level of CCLW in broiler diet. Pelleting significantly (p<0.05) improved nutrient retention compared to mash form (68.70 vs. 60.52% for CP, 72.03 vs. 60.41% EE and 71.64 vs. 63.33% for CF). Abdominal fat pad weight was significantly (p<0.05), reduced with increasing concentration of CCLW in the diet when fed in mash form, however pelleting significantly increased abdominal fat weight on all dietary treatments. The level of CCLW in the diet did not significantly affect breast and thigh weights but the form of feed presentation significantly influenced the weight of Recibido: 21-9-05. Aceptado: 17-1-08. these two choice retail cuts. Serum total protein was depressed with increasing level of CCLW but not affected by the form of feed presentation. The data obtained from these series of studies indicate that CCLW is a potentially useful feed material for monogastric feeding. RESUMEN Doscientos treinta y cuatro pollos broiler de dos semanas, criados sobre el suelo, fueron distribuidos en 18 grupos de 13 aves cada uno después de equilibrar pesos. Aleatoriamente fueron asignados a seis tratamientos alimenticios en los cuales, 0, 12,5 y 25% del maíz, fue reemplazado (peso por peso) por yuca enriquecida con gallinaza desecada y fermentada con un filtrado ruminal (CCLW). Cada nivel de inclusión fue suministrado como harina o gránulos durante seis semanas. El experimento se realizó con arreglo a un diseño factorial 2x3. Una prueba de retención de nutrientes fue realizada durante la última semana del ensayo. Al aumentar el nivel de CCLW en forma de harina, se redujo significativamente (p<0,01) la ganancia media diaria de peso (ADG) y el peso medio final (AFW). La retención de la proteína bruta (CP), fibra bruta (CF) y extracto etéreo (EE) fue deprimida significativamente (p<0,01) al aumentar el nivel de CCLW en la dieta. Arch. Zootec. 57 (218): 247-258. 2008. ADEYEMI, ERUVBETINE, OGUNTONA, DIPEOLU AND AGUNBIADE La granulación mejoró significativamente (p<0,05) la retención de nutrientes en comparación con la harina (68,70 vs. 60,52% para CP, 72,03 vs. 60,41% para EE y 71,64 vs. 63,33% para CF). El peso de la grasa abdominal se redujo de manera significativa (p<0,05) al aumentar la concentración de CCLW en forma de harina, mientras que la granulación, aumentó significativamente el peso de grasa abdominal en todos los tratamientos. El nivel de CCLW en la dieta no afectó significativamente al peso de pechuga y muslo, pero la forma de presentación del pienso afectó significativamente al peso de esas piezas comerciales. La proteína sérica total se deprimió al aumentar el nivel de CCLW pero no fue afectada por la forma de presentación. Los datos obtenidos en estos estudios indican que CCLW es un alimento potencialmente útil para alimentación de monogástricos. meal. Adeyemi and Sipe (2004), reported an improvement in crude protein concentration of cassava root when fermented with rumen filtrate with or without ammonium sulphate as the source of nitrogen. Adeyemi et al. (2004) obtained a of 237.8 % increase in the crude protein value of whole cassava root meal fermented with rumen filtrate using caged layer waste as source of nitrogen. The same product was used in this experiment as replacement for maize in diet of starter/finishing broilers presented in the form of mash and pelleted diets. The effect on growth performance, nutrient retention, carcass evaluation and serum chemistry were evaluated. INTRODUCTION MATERIALS AND METHODS Cassava (Manihot esculenta) is a widely cultivated crop in the tropics. It is the highest supplier of carbohydrates among staple crops (FAO, 1995). Annual production estimate in Nigeria was 34 million tonnes in 2002 (FAO, 2002). Cassava products had been in use for a long time as an energy source in place of cereal grains for livestock (Eruvbetine et al., 2003). There is thus the likelihood of continued use of cassava in animal feeding in the 2st century and beyond. The potentials of cassava as a feed ingredient is not withstanding, cassava is much lower in protein content. Furthermore, its protein is of poorer quality compared to that of cereal grain. When utilized in replacing cereals in diet for monogastric animals, it becomes imperative to balance for protein deficiencies, which are sometimes expensive (Agunbiade et al., 2001). There is thus the need to identify means of improving the protein quality of cassava, especially those that can be easily adapted on the farm. Noomhorm et al. (1992) reported that the conversion of a part of the starch in cassava root meal (CRM) to protein by microbes during the process of solid-state fermentation has great potential as a means of improving the feeding value of cassava root CASSAVA ROOT PROCESSING AND FER MENTATION Fresh cassava roots (12 months old, variety TMS30572) were washed to dislodge all adhering soil and mashed whole (unpeeled) using a petrol-operated grater. The cassava root meal was placed on a perforated tray, steam gelatinized over a water bath for 30 minutes and cooled. The gelatinized cassava root meal was placed in plastic containers mixed with the nitrogen source (caged layer waste) at the rates of 75 g/kg. Content of the plastic container was sprayed with rumen filtrate at the rate of 1litre per 5 kg of cassava, made airtight and fermented for duration 72 hours. Composition of the fermented product was determined as: 12.88% crude protein; 2.20% ether extract; 6.34% crude fibre; 6.21% ash; 0.24% Ca. EXPERIMENTAL DIETS AND PREPARATION Six dietary treatments were formulated (table I). Diet 1 (control) contained 0% fermented cassava root meal (CCLW). Diet 2 was formulated by replacing 25% of the maize in diet 1 with CCLW. In diet 3 CCLW replaced 50% of the maize in diet 1. The replacement of maize with fermented cassava Archivos de zootecnia vol. 57, núm. 218, p. 248. DIETS CONTAINING CASSAVA ROOT MEAL FERMENTED WITH RUMEN FILTRATE pen measuring 1 x1.5m in a conventional open-sided poultry house. All birds were subjected to standard management and health practices. Feeds and water were provided ad libitum during the experimental period that lasted for 6 weeks. Data collected during the experiment include: feed intake, weight gain, feed conversion, protein efficiency ratio and mortality (death, if any, in each replicate was recorded appropriately). root meal was on a quantitative (W/W) basis. All other ingredients remain constant. Diet 4,5 and 6 are in the form of pellets and are of the same formulation as diets 1, 2 and 3 respectively. MANAGEMENT OFBIRDSAND DATACOLLECTION 234- two weeks old broiler chicks were selected from a larger flock that had been previously floor brooded and raised on a standard commercial diet. These birds were distributed into 18 groups of 13 birds each after balancing for live weights. The eighteen groups were then randomly allocated to the six dietary treatments (table I) such that each experimental diet was fed to 3 replicates of 13 birds each. The birds were raised in deep litter pens with dry wood-shavings as litter material. Each replicate were housed in METABOLIC STUDIES At the end of the 5 th week of feeding experimental diets, two chickens per replicate whose weights were close to the mean weight of the replicate were selected and housed 2 per cell in galvanized iron battery cells with wire mesh for easy Table I. Composition of experimental diets fed to broilers (%). (Composición de las dietas experimentales consumidas por las aves). Dietary treatment 1 Mash 2 3 4 Pellets 5 6 Ingredients (%) Maize Wheat offal (<7% fiber) Enriched cassava (CCLW) Soybean meal Fish meal Oyster shell Bone meal Lysine Methionine Salt Premix* Total 50.00 11.00 30.00 4.50 1.00 2.50 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25 100.0 37.50 11.00 12.50 30.00 4.50 1.00 2.50 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25 100.0 25.00 11.00 25.00 30.00 4.50 1.00 2.50 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25 100.0 50.00 11.00 30.00 4.50 1.00 2.50 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25 100.0 37.50 11.00 12.50 30.00 4.50 1.00 2.50 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25 100.0 25.00 11.00 25.00 30.00 4.50 1.00 2.50 0.25 0.25 0.25 0.25 100.0 Determined analysis Dry matter Crude protein (%) Ether extract Crude fibre 91.05 22.51 3.08 4.12 91.40 23.30 2.64 5.50 91.25 23.75 2.90 5.92 89.35 22.55 3.15 4.10 89.10 23.18 2.70 5.45 89.20 23.70 2.62 5.80 *Provide the following per kg of feed: Vit A 10 000 000 iu; Vit D3 2 000 000 iu; Vit B 1 0.75 g; Vit B2 5 g; Nicotinic acid 25 g; Calcium pantothenate 12.5 g; Vit B 12 0.015 g; Vit K3 2.5 g; Vit E 25 g; Biotin 0.05 g; Folic acid 1 mg; Choline chloride 250 g; Co 0.4 g; Cu 8 g; Mn 64 g; Fe 32 g; Zn 40 g; I 0.8 g; Flavomycin 100 g; Spranycin 5 g; 3-Nitro 50 g; DL-Methionine 50 g; Se 0.16 g; L-Lysine 120 g; BHT 5 g. Archivos de zootecnia vol. 57, núm. 218, p. 249. ADEYEMI, ERUVBETINE, OGUNTONA, DIPEOLU AND AGUNBIADE Table II. Main effects of CCLW level and form of feed presentation on broilers performance characteristics (2-8 weeks). (Principales efectos del nivel de CCLW y de la forma de presentación del alimento sobre las características de la producción de los pollos (2-8 semanas). Parameter AVG AFW ADMI Feed/Grain. Level of CCLW (%) 0 12.5 25 Feed Form Mash Pellet SEM SEM Interaction LevelxForm 35.23 a 33.37 b 31.12 c 0.346 *** 31.33 b 35.15 a 0.283*** 1688.27 a 1612.99 b 1512.16c 17.00 *** 1512.32b 1696.63 a 10.74*** 86.89 b 89.52 a 0.486 ** 93.35 a 83.63 b 0.434*** 89.05 a b b a ** a b 2.54 2.61 2.92 0.029 3.01 2.37 0.026 ** ** ** ** ** AVG Average daily gain (g); AFW Average final weight (g); ADMI Average daily DM feed intake (g). Figures in a row, respective of diet and feed form, bearing different superscripts are significantly different (**p<0.01, ***p<0.001). collection of droppings. A 3-day acclimatization period was allowed before a 4-day collection period. The cages were housed in an open sided poultry pen. During the digestibility trial, data on the daily feed consumption were collected. The droppings were collected daily after the initial acclimatization period on previously weighed aluminum foil using the total collection method as described by Cullison (1982). Such daily droppings from each cell were weighed fresh and oven dried at 70°C for 72 hours. Thereafter, the faecal droppings for each replicate were pooled together ground and kept for analysis and subsequent determination of apparent retention and digestibility of nutrients. CARCASS EVALUATION At the end of the metabolic studies, two birds in each replicate were weighed, tagged and slaughtered by cutting the vena cava. Blood samples were taken for haematology and serum chemistry analysis by collecting blood in 2 containers each with and without EDTA. The head, crop and shank were removed and the carcass eviscerated for calculation of dressing percentage. The different parts: thigh, drumstick, neck, wing, breast-cut and back cut were weighed. In addition, organs including the pancreas, heart, liver, kidney, gizzard, spleen Table III. Interaction effects of CCLW level x form of feed presentation on broiler performance.(2-8 weeks). (Efecto de interacción de los niveles de CCLW x forma de presentación sobre la producción de pollos (2-8 semanas)). CCLW Level Parameter Mash 0 Pellet Mash 12.5 Pellet Mash 25 Pellet SEM AVG AFW ADMI Feed/Grain 33.61 b 1617.25 bc 95.73 a 2.85b 36.85 a 1759.29 a 82.37 d 2.23d 32.49 b 1549.28 c 90.95 b 2.83b 34.26 b 1676.70 b 82.84 cd 2.39cd 27.89 c 1370.42 d 93.36 ab 3.35a 34.34 b 1653.90 b 85.67 c 2.49c 0.490** 17.00** 0.69** 0.04** AVG Average daily gain (g); AFW Average final weight (g); ADMI Average daily DM feed intake (g). Figures in a row bearing different superscripts are significantly different (**p<0.01). Archivos de zootecnia vol. 57, núm. 218, p. 250. DIETS CONTAINING CASSAVA ROOT MEAL FERMENTED WITH RUMEN FILTRATE and the lungs were excised out and weighed. CHEMICAL AND ANALYTICAL PROCEDURE Proximate analysis The proximate analysis of the experimental diets and droppings were carried out using the method of AOAC (1995). Haematological and serum analysis Blood collected in tubes containing EDTA were analysed for haematological parameters including haemoglobin (Hb), packed cell volume (PCV), white blood cell (WBC) count and Red blood cell (RBC) count. The cell counts were carried out by the use of haemocytometer while Hb, PCV and serum chemistry indices were determined using standard methods (Baker and Silverton, 1985). Statistical analysis All data collected were subjected to statistical analysis appropriate for a 2 x 3 factorial design using Minitab Analytical computer package (Minitab Inc., 1989). Significant means were separated using Duncan's multiple range test (Duncan, 1955). RESULTS PERFORMANCE CHARACTERISTICS General comparison of the dietary treatment across the form of presentation revealed highly (p<0.01) significant differences in ADG, AFW, ADFI and F:G (table II). The effect of interaction between CCLW, level and feed form was significant for ADG, AFW, ADFI and F:G (p<0.01) (table III). In all measured performance indices, birds on the control diet gave better performance compared to birds on the CCLW based diets. Pelleting of diets improved the performance of birds to the extent that birds on the pelleted cassava diets performed better than the birds on the control diet fed in the meal form. Mortality recorded during the experiment was observed in birds on diet 3 (diet in which 50% of the maize was replaced by enhanced cassava). E FFECT OF DIETARY TREATMENTS ON NUTRIENT RETENTION Nutrient retention data, presented in table IV indicated that form of feed presentation had highly significant (p<0.001) effect on CP, EE and CF retention. CP, CF (p<0.001) and EE (p<0.01) retentions were affected by dietary level of CCLW inclusion level. With respect to CP retention, there was a decrease in values with increasing concentration of cassava in the diet irrespective of form of feed presentation. However, the pelleted cassava diets were better retained compared to the mash form and compared favorably with the mash control diet (table V). RETAIL CUTS AND ORGAN MEASUREMENTS Retail cuts data for which significant diet x feed form interaction occurred are shown in table VIII. Table IV. Main effects of level of CCLW and form of feed on nutrient retention. (Principales efectos del nivel de CCLW y la forma de presentación del pienso sobre la retención de nutrientes). Parameter Crude protein Ether extract Crude fiber Level of CCLW (%) 0 12.5 25 SEM 65.24 b 65.85 ab 66.55 b 0.534*** 0.442 ** 0.279*** 68.58 a 67.67 a 69.69 a 60.01 c 65.16 b 66.22 b Feed form Mash Pellet 60.52 b 60.41 b 63.33 b 68.70 a 72.03 a 71.64 a SEM Interaction LevelxFeed 0.436*** 0.361*** 0.228*** ** ** ** Figures in a row, respective of CCLW level and feed form, bearing different superscripts are significantly different (**p<0.01, ***p<0.001). Archivos de zootecnia vol. 57, núm. 218, p. 251. ADEYEMI, ERUVBETINE, OGUNTONA, DIPEOLU AND AGUNBIADE Table V. Interaction effects of CCLW level x form of feed presentation on nutrient retention. (Efecto de interacción del nivel de CCLW x forma de presentación del alimento sobre la retención de nutrientes). Level of CCLW Parameter Mash 0 Pellet Mash 12.5 Pellet Mash 25 Pellet SEM Crude protein Ether extract Crude fibre 65.85 b 63.46 b 68.25 b 71.31 a 71.87 a 71.14 a 61.29 c 59.65 c 60.91 c 69.17 a 72.04 a 72.19 a 54.41 d 58.12 c 60.83 c 65.61 b 72.19 a 71.60 a 0.756** 0.626** 0.395*** Figures in a row bearing different superscripts are significantly different (**p<0.01, ***p<0.001). There were no significant (p>0.05) effect of dietary treatment on breast weight and thigh weight (table VI). Increasing the CCLW level in dietary treatments significantly reduced abdominal fat (p<0.01), and liveweight, dressing percentage and drumstick weight (p<0.001). However, form of feeds significantly (p<0.001) influenced abdominal fat, dressing percentage, breast drumstick and thigh weights of broiler chickens, with birds fed pelleted diets generally having higher values than those given mash diets. In addition, there was a tendency for significant interaction effects of dietary treatment and feed form on dressing percentage, live-weight, abdominal fat and weight of drumstick (p<0.01). As indicated in table VII, level of cassava had no effect (p>0.05) on weight of liver, kidney, crop, spleen and gizzard. However there was an effect on weight of heart and lungs, (p<0.01) and pancreas, proventriculus and caecum (p<0.05). The values for birds fed the CCLW-based diets were generally significantly higher than for birds on the control diet. Form of feed had a highly significant effect on weight of crop, lungs, gizzard, proventriculus and caecum (p<0.001), and liver, heart and pancreas (p<0.01). Cassava inclusion level and form of feed interaction were not significant for organ weight measurements (p>0.05). HAEMATOLOGY AND BLOOD CHEMISTRY Dietary treatment had no influence (p>0.05) on packed cell volume (PCV), red blood cell counts and haemoglobin. Serum Table VI. Main effects of CCLW level and form of feed of presentation on retail cuts. (Principales efectos del nivel de CCLW y forma de presentación del pienso sobre las piezas comerciales). Parameter Liveweight (g) Dressing % Breast 1 Drumstick1 Thigh1 Abdominal fat 1 0 Level of CCLW (%) 12.5 25 SEM 1643.33a 1563.33 b 1485.00c 14.94 *** 75.61 a 73.70 b 72.83 b 0.23*** 24.55 24.47 23.29 0.57NS 12.34 a 11.49 b 10.99 b 0.16*** 12.05 12.04 12.22 0.31NS 1.48 a 1.27ab 1.22b 0.05** Feed form Mash Pellet 1483.33b 1644.44 a 71.24 b 76.85 a 20.66 b 27.54 a 10.67 b 12.55 a 10.08 b 14.12 a 1.12b 1.52a SEM 12.19*** 0.19*** 0.47*** 0.13*** 0.25*** 0.04*** Interaction LevelxForm ** ** NS ** NS ** %LW. Figures in a row, respective of CCLW level and feed forms bearing different superscripts are significantly different (**p<0.01, ***p<0.001). 1 Archivos de zootecnia vol. 57, núm. 218, p. 252. DIETS CONTAINING CASSAVA ROOT MEAL FERMENTED WITH RUMEN FILTRATE Table VII. Main effects of CCLW level and form of feed presentation on relative organ of broilers (%LW). (Principales efectos del nivel de CCLW y forma de presentación del pienso sobre el peso relativo de los órganos de pollos, % LW). Parameter Liver Kidney Heart Crop Spleen Lung Gizzard Pancreas Proventriculus Caecum Level of CCLW (%) 0 12.5 25 2.04 0.56 0.43c 0.495 0.112 0.497 b 1.728 0.203 c 0.330 c 0.303 c 1.89 0.55 0.44b 0.487 0.113 0.535 ab 1.810 0.208 b 0.343 b 0.308 b Feed form Mash Pellet SEM 2.10 0.54 0.48a 0.493 0.116 0.572 a 1.925 0.228 a 0.365 a 0.338 a 0.06NS 0.018NS 0.009 ** 0.01NS 0.006NS 0.014 ** 0.072NS 0.006 * 0.007 * 0.006 * 1.88b 0.57 0.47a 0.542 a 0.118 0.580 a 2.09a 0.229 a 0.376 a 0.339 a 2.14a 0.53 0.43b 0.441 b 0.109 0.489 b 1.54b 0.197 b 0.317 b 0.294 b SEM Interaction LevelxForm 0.049** 0.015NS 0.007** 0.008*** 0.005NS 0.011*** 0.059*** 0.005** 0.006*** 0.005*** NS NS NS NS NS NS NS NS NS NS Figures in row, respective of CCLW level and feed form; bearing different superscripts are significantly different (*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001). chemistry indices were significantly (p<0.01) influenced by dietary treatment (table IX). Similarly, feed form influenced haemoglobin and serum albumin (p<0.01), serum globulin (p<0.001) and albumin:globulin ratio (p<0.01) but had no influence on serum total protein (p>0.05). The interaction effect of dietary treatment and form of feed significantly influenced serum albumin (p<0.001), serum globulin and albumin ratio (p<0.01) (table X). DISCUSSION The significant reduction in ADG and AFW of broilers with increasing dietary level of CCLW from 0 to 25% of total diet at the expense of maize when fed in mash form is in agreement with earlier reports (Akinfala et al., 2003) but contrary to the report of Gomez et al. (1988). Eruvbetine and Afolami (1992) observed that the inclusion of cassava root meal up to 30% in diets for broilers had no detrimental effects on body weight. Akinfala et al. (2003) reported growth impairments of 13 and 19% of control (containing 0% of cassava) when starter broilers were fed diets containing 12.5 and 25% of whole cassava plant meal. Eruvbetine Table VIII. Interaction effects of cassava level x form of feed presentation on retail cuts. (Efectos de interacción del nivel de CCLW x forma de presentación del pienso sobre las piezas comerciales). Level of CCLW Parameter 0 Mash Liveweight (g) 1586.67bc Dressing (%) 73.31 c Drumstick (%LW) 12.05a Abdominal fat (%LW) 1.27c 12.5 25 Pellet Mash Pellet Mash Pellet SEM 1700.00 a 77.91 a 12.63 a 1.78a 1510.00c 71.01 d 10.39 b 1.11d 1616.67ab 76.38 b 12.60 a 1.29 c 1353.33d 69.39 e 9.56b 0.94e 1616.67ab 76.27 b 12.42 a 1.50b 21.13** 0.33** 0.22** 0.07** **Figure in a row bearing different superscripts are significantly different (p<0.01). Archivos de zootecnia vol. 57, núm. 218, p. 253. ADEYEMI, ERUVBETINE, OGUNTONA, DIPEOLU AND AGUNBIADE Table IX. Main effects of CCLW level and form of feed presentation on haematology and serum chemistry of broilers. (Principales efectos del nivel de CLLW y la forma de presentación del pienso sobre la hematología y química del suero de las aves). Parameter PCV RBC WBC Hb STP SA SG Albumin/globulin Level of CCLW (%) 0 12.5 25 28.22 3.19 33.52 a 8.62 6.40a 4.14b 2.26a 1.83b 28.81 3.23 31.89 b 8.56 6.15c 4.00b 2.15a 1.88b SEM 28.51 3.23 31.64 b 8.60 6.28b 4.40a 1.89b 2.53a 0.268NS 0.049NS 0.253 ** 0.047NS 0.018 ** 0.051 ** 0.530 ** 0.115 ** Feed form Mash Pellet 28.72 3.21 32.40 8.68 a 6.29 4.02 b 2.27 a 1.77 b 28.30 3.22 32.30 8.50b 6.26 4.34a 1.92b 2.39a SEM Interaction LevelxForm 0.219NS 0.04NS 0.21NS 0.04** 0.15NS 0.042 ** 0.043*** 0.094 ** NS NS NS NS NS *** ** ** PCV Packed cell volume %; RBC Red blood cell x106mm-3 ; WBC White blood cell x103mm-3; Hb Haemoglobin; STP Serum total protein; SA Serum albumin; SG Serum globulin. Figures in a row, respective of CCLW level and feed form bearing different superscripts are significantly different (**p<0.01, ***p<0.001). et al. (2003) explained that the decline in body weight of birds with increasing concentration of cassava root: leaf meal concentrate (50:50) might have been due to the presence of high fiber. Feed intakes of CCLW based mash diets were slightly lower than the mash control diet. The lower feed intake compared to control may be related to the adequacy of dietary energy. Birds are known to eat in order to satisfy their energy need, thus in a situation of adequate dietary energy, feed intake will be low. The response of broilers (ADG, AFW and F: G) on 12.5% CCLW diet was not significantly different from those of birds on the control diet (0% cassava) when fed in mash form. This study revealed that the 12.5% CCLW diet was slightly more efficient than the control (2.83 vs. 2.85 F: G ratio). An improvement in growth performance indices was observed when the diets were fed in pelleted form, to the extent that the diet containing CCLW when fed in pelleted form compared favourably with the mash control version. Generally, the data showed that ADG and AFW were better on the pelleted diets compared with the corres- Table X. Interaction effects of CCLW level x form of feed presentation on haematology and serum chemistry of broilers. (Efectos de interacción del nivel de CCLW x forma de presentación del pienso sobre la hematología y química del suero de broilers). Level of CCLW Parameter Mash 0 Pellet Mash 12.5 Pellet Mash 25 Pellet SEM Serum albumin Serum globulin Albumin/globulin 4.16b 2.27a 1.84b 4.11 b 2.26 a 1.82 b 3.89 b 2.27 a 1.71 b 4.11b 2.03a 2.04b 4.02b 2.27a 1.77b 4.78a 1.48b 3.29a 0.072*** 0.074** 0.162** Figure in a row bearing different superscripts are significantly different (**p<0.01, ***p<0.001). Archivos de zootecnia vol. 57, núm. 218, p. 254. DIETS CONTAINING CASSAVA ROOT MEAL FERMENTED WITH RUMEN FILTRATE ponding mash diets. ADG of birds on pelleted diets improved by 9.63, 5.45, and 23.13% respectively over the control, 12.5% CCLW and 25% CCLW based diets fed in the mash form. AFW improved by 8.78, 8.22 and 20.69% for birds on pelleted version of diets 1,2 and 3 respectively. The significant improvement brought about by pelleting on growth performance of broilers observed in the present work agrees with previous findings of Auckland and Fulton (1972) but contrary to the reports of Hull et al. (1968) and Agunbiade (2000). Fowls prefer feed in particulate form rather than mash; the preference decreases the work of prehension, time spent standing at the feeder and competition for food (Reddy et al., 1962; Jensen et al., 1962; Savory, 1974). Moran (1989) explained that the mouth of the fowl is particularly well suited to benefit from pellets as immobility of the beak creates problems in apprehending finely divided feeds. Auckland and Fulton (1972) observed that broiler chicks fed crumbles grew 9 and 6% faster than those fed mash when given low and high energy feeds respectively. The superior performance of birds on the pelleted diets compared to those on mash supports the observation of Patterson et al. (1991) that pelleting increased weight gain of chickens. In the present study, the observation that pelleted diets were more efficiently converted than the mash may be because the chicken spent less time feeding on pellets and expended less energy than on mash (Savory, 1974; Moran, 1989; Nir et al., 1994). Patterson et al. (1991) surmised that the main effect of pelleting on feed utilization is a reduction in feed energy devoted to maintenance and therefore improved productive energy hence the better weight gains observed on pelleted diets. The integrity and quality of pellets affect birds' performance on pelleted diets. Plavnik et al. (1997) reported that the growth response of birds to pelleting when energy was added, as fat supplementation was lower than when added in the form of carbohydrates, possibly because of a decline in pellet quality as dietary fat content increased. The mortality recorded in this trial although limited to birds on diet containing 25% CCLW (fed in mash form) was not directly due to experimental treatment. The post mortem showed that mortality recorded on the diets was due to coccidiosis and was not directly linked to the experiment since the droppings of all birds used in the experiment showed the diagnostic bloody droppings observed with coccidiosis. Nutrient retention data obtained in the experiment showed depression in retention of CP, EE and CF as the concentration of CCLW increased. Pelleting of diets however improved nutrient retention by broilers. The observed improvement in nutrient retention when broilers were fed pelleted as opposed to meal diets is consistent with earlier reports of Carew and Nesheim (1962), Hull et al. (1968), Mitchell et al. (1972) and Janssen et al. (1979). The need for a combination of thermal and mechanical actions in rupturing cell walls and thus making encapsulated nutrients of feedstuff more accessible to digestive enzymes was reported for pigs (Vande and Schrijver, 1988). Live weight and dressing percentage are important indices in broiler operations. Live weight pattern follows a reducing trend with increasing concentration of CCLW in the diet. The trend was similar to that reported by Eruvbetine et al. (2003) using increasing concentration of cassava leaf and tuber concentrate in broiler chickens. Dressing percentage and weight of drumstick reduced with increasing concentration of CCLW. Higher inclusion level of CCLW significantly reduced live weight and abdominal fat. The significant decrease in dressing percentage with increasing concentration of CCLW is at variance with the report of Osei and Duodu (1988) that dietary treatments had no influence on carcass quality characteristics Archivos de zootecnia vol. 57, núm. 218, p. 255. ADEYEMI, ERUVBETINE, OGUNTONA, DIPEOLU AND AGUNBIADE such as dressed weight and eviscerated weight and the report of Eruvbetine et al. (2003). It is pertinent to note however that Osei and Duodu (1988) fed fermented cassava peel meal. Although Eruvbetine et al. (2003) did not record significant effect of dietary treatment on dressing percentage, their data showed a decreasing trend with increasing concentration of leaf and tuber concentrate. The reduction in abdominal fat with increasing concentration of CCLW is in agreement with earlier works on cassava at this station (Eruvbetine, 1995; Eruvbetine et al., 2003). Eruvbetine (1995) reported that in experiments with both layers and broilers, there were marked reduction in the abdominal fat content of broilers at market weight and layers after 40wks in lay as a result of cassava inclusion. The reason for this reduction can be related to the crude fiber component of the diet. A similar reason can be adduced for the higher weights of proventriculus and caecum in this study with increasing concentration of CCLW. The higher percentage of breast meat, drumstick and thigh, which are the most expensive commercial cuts of the chicken, in birds fed pelleted diets over those of mash is an index of superiority of pelleted diets in broiler feeding on account of the degree of carcass meatiness and revenue yield. Similar observation have been reported previously (Havorson et al., 1991; Bartov, 1998; Agunbiade, 2000). Abdominal fat (%) was however higher on the pelleted diet a finding in agreement with earlier reports of Howlider and Rose (1992), Reddy and Narahari (1993), Nir et al. (1994), Plavnik et al. (1997) and Agunbiade (2000). The corresponding increase in body fat due to pelleting negates the overall advantage of pelleting on carcass quality. It is equally important to note that although abdominal fat content were higher on pelleted diets compared to the mash form, birds on the cassava based pelleted diets have lower abdominal fat compared to the maize based pelleted control diet. The higher abdominal fat content in broilers fed pelleted diets is thought to be as result of the greater ether extract retention. The result of this study showed that pelleted CCLW based diet led to a significant reduction in relative weights of various parts of the GIT. Choi et al. (1986) observed that various parts of the gastrointestinal system in broiler chickens given pelleted feed had reduced weight relative to the body. Moran (1989) explained that pelleted feed would appear to reduce the extent of mortality and other work associated with the GIT. Agunbiade (2000) observed a similar reduction in the gizzards of broiler fed pelleted diets and opined that the gizzard easily broke down pelleted diets. Attempts by birds on the meal diet for increased capacity of the GIT (particularly the gizzard) to allow for improved nutrient utilization and growth performance could lead to the enlargement of the gizzard in this study. Haematocrit, erythrocytes and haemoglobin are known to be positively correlated with protein quality and protein level. Brown and Clime (1972) observed that decreased red blood cell count is usually associated with low quality feeds and protein deficiency. PCV is an indicator of blood dilution (Wilson and Brigstoke, 1981), haemoglobin measures the ability of an animal to withstand some level of respiratory stress (Sainsbury, 1983). The values obtained for the red blood cell count and packed cell volume for all the diets fall within the normal range established by Mitruka and Rawnsley (1977). Allison (1955) observed that total protein value is an indication of the protein reserve in an animal. The significant reduction in serum total protein of birds on CCLW based diets compared to the control may be a reflection of the inadequacy of dietary protein, even though there was no particular pattern. In conclusion, the data obtained from Archivos de zootecnia vol. 57, núm. 218, p. 256. DIETS CONTAINING CASSAVA ROOT MEAL FERMENTED WITH RUMEN FILTRATE this study indicate that protein-enriched cassava meal can be an useful foodstuff in poultry nutrition. The productive results are better when diets containing this novel foodstuff are presented in pelleted form in comparison with mash form. REFERENCES AOAC. 1995. Official Methods of Analysis. 16 th edition. Association of Official Analytical Chemists. Washington D.C. Adeyemi, O.A and B.O. Sipe. 2004. In vitro improvement in the nutritional composition of whole cassava root-meal by rumen filtrate fermentation. Indian J. Anim. Sci., 74: 321323. Adeyemi, O.A., D. Eruvbetine, T.O. Oguntona, M.A. Dipeolu and J.A. Agunbiade. 2004. Improvement in the crude protein value of whole cassava root meal by rumen filtrate fermentation. In: Sustaining Livestock Production under Changing Economic Fortunes Proceedings 29th Annual Conference, Nig Soc. Animal Production. Eds. H.M. Tukur, W.A. Hassan, S.A. Maigandi, J.K. Ipinjolu, A.I. Danejo, K.M. Baba and B.R. Olorede. p: 1-5. Agunbiade, J.A. 2000. Utilisation of two varieties of full fat and simulated soybeans in meal and pelleted diets by broiler chickens. Polym. Int., 49: 1529-1537. Agunbiade, J.A., O.A. Adeyemi, O.E. Fasina and S.A. Bagbe. 2001. Fortification of cassava peel meal in balanced diets for rabbits Nig. J. Anim. Prod., 28: 167-173. Akinfala, E.O., A.O. Aderibigbe and O. Matanmi. 2003. Evaluation of the nutritive value of whole cassava plant as replacement for maize in the starter diets for broiler chicken. Liv. Res. Rural. Dev., 14: 1-6. Allison, J.B. 1955. Biological evaluation of proteins. Physiol. Rev., 35: 664-669. Auckland, J.N and R.B Fulton. 1972.The effects of dietary nutrient concentration, crumbles versus mash and age of dam on the growth of broiler chicks. Poult. Sci., 51: 1968-1975. Baker, F.J and R.E Silverton. 1985. Introduction to medical laboratory technology. 6th ed. Butterworth. England. Bartov, I. 1998. Lack of interrelationship between the effects of dietary factors and food withdrawal on carcass quality of broiler chickens. Brit. Poult. Sci., 39: 426-433. Brown, J.A and T.R. Clime. 1972. Nutrition and haematological values. J. Anim. Sci., 35: 211218. Carew, L.B and M.C. Nesheim. 1962. The effect of pelleting on the nutritional value of ground soybean for chick. Poult. Sci., 41: 161-168. Choi, J.H, B.S. So, K.S. Ryu and S.L. Kang. 1986. Effects of pelleted or crumbled diets on the performance and the development of the digestive organs of broilers. Poult. Sci., 65: 594-597. Cullison, A.E. 1982. Feeds and feeding. 3rd edition. Reston Publishing Co, Virginia. Duncan, D.B. 1955. Multiple range and multiple Ftests. Biometrics, 11: 1-42. Eruvbetine, D. 1995. Processing and utilization of cassava as animal feed for non-ruminant animals. Paper presented at the Workshop on Alternative Feedstuff for Livestock organized by Lagos State Ministry of Agric. Cooperatives and Rural Development. Eruvbetine, D. and C.A. Afolami. 1992. Economic evaluation of cassava (M. esculenta) as a feed ingredient for broilers. In: Proc. World's Poultry Congress. Amsterdam, Netherlands. Vol. 3, p. 151-155. Eruvbetine, D., I.D. Tajudeen, A.T. Adeosun and A.A.Olojede. 2003. Cassava (M. esculenta) leaf and tuber concentrate in diets for broiler chickens. Biores. Tech., 86: 277-281. FAO. 1995. Commodity review and outlook, 199495. Economic and Social Development Series. Food and Agriculture Organization. Rome, Italy. FAO. 2002. FAOSTATstatisticsdatabase. (http:// aps.fao.org). June (accessed July). Gomez, G., M. Aparicio and C. Willihite. 1988. Relationship between dietary cassava cyanide levels and broiler performance. Nutr. Reports Intl., 37: 63-75. Havorson, J.C., P.E. Waibel, E.M.Oju, S.L. Noil and M.E. El- Halawani. 1991.The effect of diet and population density on male turkeys under various environmental conditions. 2. Body composition and meat yield. Poult. Sci., 70: 935-940. Archivos de zootecnia vol. 57, núm. 218, p. 257. ADEYEMI, ERUVBETINE, OGUNTONA, DIPEOLU AND AGUNBIADE Howlider, M.A.R. and S.P. Rose. 1992. The response of growing male and female broiler chickens kept at different temperature to dietary energy concentration and feed form. Anim. Feed. Sci. Tech., 39: 71-78. Hull, S.J., P.W. Waldroup and E.L. Stephenson. 1968. Utilisation of unextracted soybeans by broiler chicks. 2. Influence of pelleting and regrinding on diets with infrared cooked and extruded soybeans. Poult. Sci., 47: 1115-1120. Janssen, W.M., K. Terpstra, F.F.E. Beeking and A.J. Nbisalksky. 1979. Feeding values for poultry. 2 nd Edition. Spelderholt Centre for Poultry Reseach and Extension, Beekbergen. Jensen, L.S., L.N. Merrill, C.V. Reddy and J.Mcginnis. 1962. Observations on eating patterns and rate of food passage of birds fed pelleted and unpelleted diets. Poult. Sci., 41: 1414-1419. Minitab Inc. 1989. Minitab data analysis system. Release 7.1 Standard Version Serial. Mitchell, R.J, P.W. Waldroup, C.M. Hillard and K.R. Hazen.1972. Effects of pelleting and particle size on utilization of roasted soybeans by broilers. Poult. Sci., 51: 506-510. Mitruka, B.M and H.M Rawnsley. 1977. Clinical, biochemical and haematological reference value in normal experimental animals. Mason Publishing Co. New York. p. 171-174. Moran, E.T. Jr. 1989. Effect of pellet quality on the performance of meat birds. In: Recent advances in animal nutrition. Butterworths. London. p. 87108. Nir, I., Y. Twina, E. Grossman and Z. Nitsan. 1994. Quantitative effects of pelleting on performance gastro-intestinal track and behaviour of meat type chickens. Br. Poult. Sci., 35: 589-602. Noomhorm, A.S., S. Ilangitileke and M.B. Bautista. 1992. Factors in the protein enrichment of cassava by solid state fermentation. J. Sci. Food. Agric., 58: 117-123. Osei, S.A. and S. Duodu. 1988. Effects of fermented cassava peel meal on the performance of broilers. Br. Poult. Sci., 29: 671-675. Patterson, E., H. Graham and P. Aman. 1991. The nutritive value for broiler chickens of pelleting and enzyme supplementation of a diet containing barley, wheat and rye. Anim. Feed Sci. Tech., 33: 1-14. Plavnik. J., E. Wax, D. Sklan and S. Hurtwtz. 1997. The response of broiler chicken and turkey poult to steam- pelleted diets supplemented with fat or carbohydrates. Poult. Sci., 76: 1006-1013. Reddy, C.V., L.S. Jensen, L.N. Merrill and J. MacGinnis. 1962. Influence of pelleting on metabolisable and productive energy content of a complete diet for chicks. J. Nutr., 77: 428-433. Reddy, P.S and D. Narahari. 1993. Effect of dietary energy level and pelleting of feed on the performance of broiler chicks in the tropics. Indian J. Anim. Sci., 63: 478-480. Sainsbury, D. 1983. Animal Health. 1st Edition. Granada Publishers Ltd. New York. Savory, C.J. 1974. Growth and behaviour of chicks fed on pellet or mash. Br. Poult. Sci., 152: 281-286. Vande, G.H and R. Schrijver. 1988. Expansion and pelleting of starter grower and finishers diets: effects on nitrogen retention, ileal and total tract digestibility of protein phosphorus and calcium and in vitro protein quality. Anim. Feed. Sci. Tech., 72: 303-318. Wilson, P.N. and T.O.A. Brigstocke. 1981. Improved feeding of cattle and sheep: A practical guide to modern concept of ruminant nutrition. Granada Publishers Ltd. New York. Archivos de zootecnia vol. 57, núm. 218, p. 258.