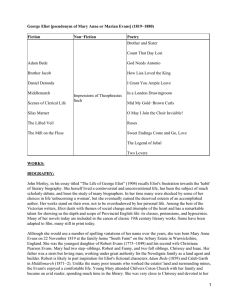

Feminismos 4 - RUA - Universidad de Alicante

Anuncio