1 ABSTRACT Do Speakers of Castilian Spanish Indeed Distinguish

Anuncio

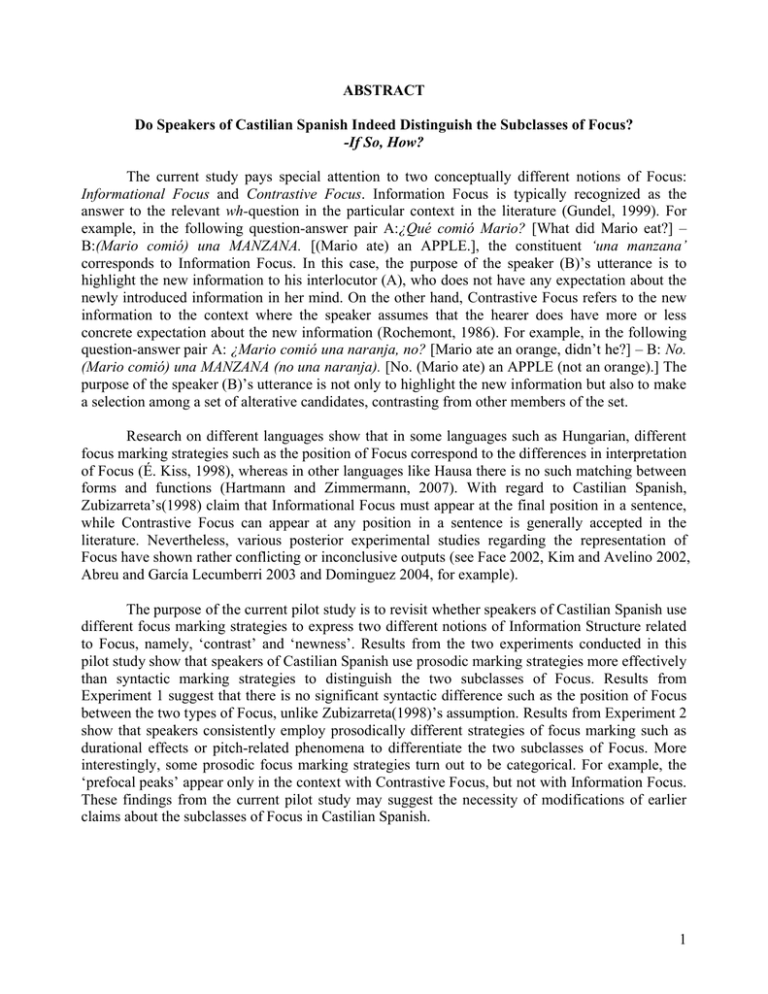

ABSTRACT Do Speakers of Castilian Spanish Indeed Distinguish the Subclasses of Focus? -If So, How? The current study pays special attention to two conceptually different notions of Focus: Informational Focus and Contrastive Focus. Information Focus is typically recognized as the answer to the relevant wh-question in the particular context in the literature (Gundel, 1999). For example, in the following question-answer pair A:¿Qué comió Mario? [What did Mario eat?] – B:(Mario comió) una MANZANA. [(Mario ate) an APPLE.], the constituent ‘una manzana’ corresponds to Information Focus. In this case, the purpose of the speaker (B)’s utterance is to highlight the new information to his interlocutor (A), who does not have any expectation about the newly introduced information in her mind. On the other hand, Contrastive Focus refers to the new information to the context where the speaker assumes that the hearer does have more or less concrete expectation about the new information (Rochemont, 1986). For example, in the following question-answer pair A: ¿Mario comió una naranja, no? [Mario ate an orange, didn’t he?] – B: No. (Mario comió) una MANZANA (no una naranja). [No. (Mario ate) an APPLE (not an orange).] The purpose of the speaker (B)’s utterance is not only to highlight the new information but also to make a selection among a set of alterative candidates, contrasting from other members of the set. Research on different languages show that in some languages such as Hungarian, different focus marking strategies such as the position of Focus correspond to the differences in interpretation of Focus (É. Kiss, 1998), whereas in other languages like Hausa there is no such matching between forms and functions (Hartmann and Zimmermann, 2007). With regard to Castilian Spanish, Zubizarreta’s(1998) claim that Informational Focus must appear at the final position in a sentence, while Contrastive Focus can appear at any position in a sentence is generally accepted in the literature. Nevertheless, various posterior experimental studies regarding the representation of Focus have shown rather conflicting or inconclusive outputs (see Face 2002, Kim and Avelino 2002, Abreu and García Lecumberri 2003 and Dominguez 2004, for example). The purpose of the current pilot study is to revisit whether speakers of Castilian Spanish use different focus marking strategies to express two different notions of Information Structure related to Focus, namely, ‘contrast’ and ‘newness’. Results from the two experiments conducted in this pilot study show that speakers of Castilian Spanish use prosodic marking strategies more effectively than syntactic marking strategies to distinguish the two subclasses of Focus. Results from Experiment 1 suggest that there is no significant syntactic difference such as the position of Focus between the two types of Focus, unlike Zubizarreta(1998)’s assumption. Results from Experiment 2 show that speakers consistently employ prosodically different strategies of focus marking such as durational effects or pitch-related phenomena to differentiate the two subclasses of Focus. More interestingly, some prosodic focus marking strategies turn out to be categorical. For example, the ‘prefocal peaks’ appear only in the context with Contrastive Focus, but not with Information Focus. These findings from the current pilot study may suggest the necessity of modifications of earlier claims about the subclasses of Focus in Castilian Spanish. 1 REFERNCES Abreu M. & M.L. García Lecumberri (2003) The Manifestation of Intonational Focus in Castilian Spanish. Catalan Journal of Linguistics 2:33-54. Dominguez, L. (2004) Effects of Phonological Cues on the Syntax of Focus Constructions in Spanish. In Romance Languages and Linguistics Theory. Bok-Bennema, Reineke, Bart Hollebrandes, Brigitte Kampers-Manhe and Petra Sleeman (eds.). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins. É. Kiss, K. (1988) Identificational Focus versus Information Focus. Language 74. 245-273. Face, T. (2002) El foco y la altura tonal en español. Boletín de lingüística¸ vol.17: 30-52. Gundel, J. (1999) On Different Kinds of Focus, in P.Bosch & R. Van der Sandt (eds.), Focus: Linguistic, cognitive and computational perspectives. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press. 293-305. Hartmann, K. & M. Zimmermann. (2007) In Place - Out of Place? Focus in Hausa. In K. Schwabe & S. Winkler (Hgg.), On Information Structure, Meaning and Form: Generalizing Across Languages. 365-403 Hualde, J.I. (2005) The Sound of Spanish. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Kim, S. & A. Heriberto (2002) An Intonation Study of Focus and Word Order Variation in Mexican Spanish. In la tonía: dimensiones fonéticas y fonológicas. Ed. E. Herrera Z. & P. Martín. Mexico: El colegio de México. Rochemont, M. (1986) Focus in Generative Grammar. Amsterdam, John Benjamins. Zubizarreta, M. L. (1998) Prosody, Focus and Word Order. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press 2 APPENDIX: Examples of Test Materials Diálogo Abuela : Oye, cielo… me he perdido la parte inicial. ¿Ahora, quién limpia el baño? [Hey, sweetie… I missed the first part (of the TV drama). Who is clearing the bathroom, now?] Bea : La fontanera( limpia el baño). Informational Focus [The (female) plumber is cleaning the bathroom.] Abuela : Ah.. La cocinera limpia el baño. ¡Qué raro! [Ah… The (cook) is cleaning the bathroom. How strange!] Bea : No, abuela. La fontanera (limpia el baño). Contrastive Focus ¿Te has quitado los aparatos auditivos? [No, grandma. The (female) plumber is cleaning the bathroom. Did you take off your hearing aid?] Abuela : Sí, sí, ahora me los pongo. [Yeah, but, I’m putting it on now.] 3