Trafficking - Actividad Cultural del Banco de la República

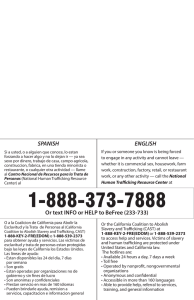

Anuncio