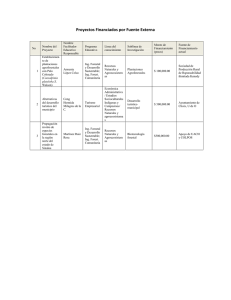

05-175 (Evaluación del Yolanda Nava)

Anuncio

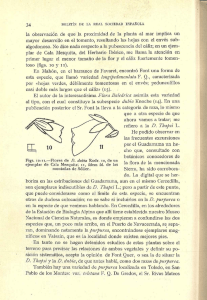

EVALUACIÓN DEL EFECTO DE BORDE SOBRE DOS ESPECIES DEL BOSQUE TROPICAL CADUCIFOLIO DE JALISCO, MÉXICO EVALUATION OF THE EDGE EFFECT ON TWO ARBOREAL SPECIES OF THE TROPICAL DRY FOREST OF JALISCO, MEXICO Yolanda Nava-Cruz1, Manuel Maass-Moreno1, Oscar Briones-Villareal2 e Ignacio Méndez-Ramírez3 1 Centro de Investigaciones en Ecosistemas. UNAM. Antigua carretera a Pátzcuaro. Número 8701. Colonia Ex-Hacienda de San José de la Huerta. 58190. Morelia, Michoacán. (ynava@ate.oikos.unam.mx). 2Instituto de Ecología, A.C. km 2.5 carretera antigua a Coatepec Número 351. Congregación El Haya, Xalapa. 91070, Veracruz, México. Apartado Postal 63. (oscar.briones@inecol.edu.mx) 3Instituto de Investigaciones en Matemáticas Aplicadas y Sistemas. UNAM. Circuito escolar. Ciudad Universitaria. 4510. México, D. F. (imendez@servidor.unam.mx) RESUMEN ABSTRACT En el manejo de ecosistemas fragmentados, es de gran relevancia comprender las repercusiones que el efecto de borde tiene sobre la vegetación remanente de dichos fragmentos. En este experimento se analizó cómo plántulas de Caesalpinea platyloba y estacas de Spondias purpurea responden al gradiente ambiental generado en el borde de dos fragmentos de bosque tropical caducifolio colindantes con potreros. Se trasplantaron 30 individuos de 8 meses de edad de C. platyloba e igual número de estacas de S. purpurea, a lo largo de 5 corredores de 5 por 50 m paralelos al borde, a distancias de 0-5, 30-35 y 75-80 m desde el borde hacia el interior del bosque, y a 0-5 y 35-40 m hacia el potrero. A cada planta se le tomaron medidas del incremento en altura y se registró su supervivencia durante 14 meses después del trasplante. Se encontró que la supervivencia de las plantas fue diferencial entre especies, con diferentes umbrales de tolerancia a la perturbación. C platyloba mostró un mayor porcentaje de supervivencia en los corredores del interior del bosque, aunque la heterogeneidad de las condiciones microambientales parece tener mayor influencia que el efecto de la distancia respecto al borde. C. platyloba mostró una mayor respuesta a los factores de la calidad del sitio que regulan su incremento en altura. In the management of fragmented ecosystems, it is of great relevance to understand the repercussions that the edge effect has on the remnant vegetation of these fragments. In this experiment, an analysis was made of how seedlings of Caesalpinea platyloba and cuttings of Spondias purpurea respond to the environmental gradient generated on the edge of two fragments of tropical dry forest bordering on grasslands. Thirty individuals of C. platyloba, 8 months of age, and the same number of cuttings of S. purpurea, were transplanted along 5 corridors of 5 by 50 m parallel to the edge, at distances of 0-5, 30-35 and 75-80 m from the edge toward the inner forest, and at 0-5 and 35-40 m toward the pasture. Measurements were taken of the height increase of each plant, and its survival was registered during 14 months after transplanting. It was found that the survival of the plants was differential among species, with different thresholds of tolerance to disturbance. C. platyloba showed a higher percentage of survival in the corridors of the inner forest, although the heterogeneity of the micro-environmental conditions appears to have greater influence than the effect of the distance with respect to the edge. C. platyloba showed a greater response to the factors of the quality of the site that regulate its height increase. Palabras clave: Caesalpinea platyloba, Spondias purpurea, Chamela, fragmentación. Key words: Caesalpinea platyloba, Spondias purpurea, Chamela, fragmentation. INTRODUCCIÓN INTRODUCTION l uso de un ecosistema induce, con frecuencia, una transformación profunda de su estructura y funcionamiento. Como resultado del uso de estos sistemas se encuentran la deforestación y la fragmentación del paisaje en el que colindan zonas de vegetación primaria con áreas transformadas. El efecto de borde se define como el conjunto de cambios que ocurren en los márgenes entre el ecosistema natural y he use of an ecosystem often induces a profound transformation of its structure and functioning. Deforestation and fragmentation of the landscape result from the use of these ecosystems, in which primary vegetation zones border on transformed areas. The edge effect is defined as the series of changes that occur at the borders between the natural ecosystem and the managed areas. In the context of this study, an edge is defined as the barrier between the primary and secondary or antropic, which in the case of the zone of E T Recibido: Noviembre, 2005. Aprobado: Diciembre, 2006. Publicado como ARTÍCULO en Agrociencia 41: 111-120. 2007. 111 AGROCIENCIA, ENERO-FEBRERO 2007 las áreas manejadas. En el contexto de este estudio, un borde se define como la barrera entre la vegetación primaria y la secundaria o antrópica, que para el caso de la zona de estudio se trata del bosque tropical caducifolio (BTC) y los potreros. En su concepto actual se define al borde como una membrana que modula el intercambio de materia y organismos entre dos hábitats, derivando en el concepto de permeabilidad de bordes (López-Barreda, 2004). El efecto de borde genera cambios a diferentes escalas y sobre diferentes variables que pueden ocasionar reducción de especies y la alteración de procesos ecosistémicos (William, 2002). Los efectos negativos de la creación de bordes incluyen una mayor mortalidad de flora y fauna cerca del borde con respecto al interior del fragmento y la consecuente reducción de su área (Harris, 1998). Camargo y Kapos (1995) han mostrado que muchas variables físicas (radiación fotosintéticamente activa, RFA), el déficit de presión de vapor (DPV), la temperatura ambiente y el contenido de agua en el suelo se modifican más allá de 40 m a partir del borde hacia el interior del bosque. Cerca del borde el ambiente es más cálido, seco e iluminado que en las zonas hacia el interior del bosque. La exposición al borde afecta también la fisiología de las plantas (BenítezMalvido y Martínez-Ramos, 2003 a). Los estudios del efecto de borde sobre dinámica y repoblación natural de la comunidad de árboles del bosque, dicen poco acerca de la variación en la respuesta de diferentes especies a la creación del borde. Hay evidencia de que la densidad de plántulas es menor en fragmentos de bosque que en bosques continuos (Benítez-Malvido y Martínez-Ramos, 2003 b). La persistencia de especies en fragmentos depende de la disponibilidad de semillas, plántulas y árboles jóvenes. Se puede evaluar experimentalmente la respuesta de la vegetación a la fragmentación usando plántulas nativas de especies conocidas, que pueden ser trasplantadas en el interior del fragmento y evaluar su respuesta (supervivencia, crecimiento, reproducción, etc.). Dada la naturaleza del Bosque Tropical Caducifolio (BTC), caracterizado por una gran diversidad biológica (Lott, 1993) y una distribución muy heterogénea, la evaluación del efecto de borde en sus poblaciones individuales requiere analizar el fenómeno a escalas muy grandes (cientos de hectáreas). Nuestro interés se centró en analizar cómo plántulas de dos especies responden al gradiente ambiental generado en el borde. La idea fue utilizar individuos jóvenes como indicadores de la respuesta de la vegetación nativa a las condiciones de borde. El presente estudio se realizó en el contexto de un estudio más amplio orientado a evaluar el efecto de 112 VOLUMEN 41, NÚMERO 1 study, is the tropical dry forest (TDF) and the pastures. In its present concept, the edge is defined as a membrane that modulates the exchange of matter and organisms between two habitats, deriving in the concept of permeability of edges (López-Barreda, 2004). The edge effect generates changes on different scales and on different variables that can cause reduction of species and the alteration of ecosystemic processes (William, 2002). The negative effects of the creation of edges include a higher mortality of flora and fauna near the edge with respect to the interior of the fragment and the resulting reduction of its area (Harris, 1998). Camargo and Kapos (1995) have demonstrated that many physical variables (photosynthetically active radiation (PAR), vapor pressure deficit (VPD), environmental temperature and soil water content are modified beyond 40 m from the edge toward the inner forest. Near the edge the environment is warmer, drier and more illuminated than in the zones toward the inner forest. Exposure to the edge also affects the physiology of plants (Benítez-Malvido and MartínezRamos, 2003 a). The studies of the edge effect on the dynamics and natural repopulation of the tree community of the forest say little about the variation in response of different species to the creation of the edge. There is evidence that the density of seedlings is lower in forest fragments than in continuous forests (Benítez-Malvido and Martínez-Ramos, 2003 b). The persistence of species in fragments depends on the availability of seeds, seedlings and young trees. The response of vegetation to fragmentation can be evaluated experimentally by using native seedlings of known species, which can be transplanted in the interior of the fragment, and then evaluating their response (survival, growth, reproduction, etc.). Given the nature of the Tropical Dry Forest (TDF), characterized by a great biological diversity (Lott, 1993) and a very heterogenic distribution, the evaluation of the edge effect in its individual populations requires an analysis of the phenomenon on a very large scale (hundreds of hectares). Our interest centers on analyzing how seedlings of two species respond to the environmental gradient generated on the edge. The idea was to utilize young individuals as indicators of the response of the native vegetation to the edge conditions. The present study was conducted within the context of a broader investigation oriented towards the evaluation of the edge effect of fragments of tropical dry forest, with the particular objective of evaluating the responses (height growth and survival) of two native arboreal species in a young stage that grow in an environmental gradient generated by the edge effect between a TDF and grasslands. EVALUACIÓN DEL EFECTO DE BORDE SOBRE DOS ESPECIES DEL BOSQUE TROPICAL CADUCIFOLIO DE JALISCO, MÉXICO borde en fragmentos de bosque tropical seco, con el objetivo particular de evaluar las respuestas (crecimiento en altura y supervivencia) de dos especies arbóreas nativas en estado juvenil que crecen en un gradiente ambiental generado por el efecto de borde entre un BTC y potreros. Área de estudio El estudio se llevó a cabo en la región de Chamela, Jalisco, México. La región de la costa de Jalisco se caracteriza por una topografía irregular, con lomeríos de 20 a 250 m y que conforman numerosos sistemas de cuencas pequeñas. La geología está representada por rocas ígneas terciarias y cuaternarias (Cotler et al., 2002). La temperatura media anual es 21.4 °C. El promedio anual de lluvia es alrededor de 718 mm (intervalo 350 a 1200 mm), con 80% de la lluvia entre julio a noviembre (García-Oliva et al., 2002). La dinámica del ecosistema está controlada en gran medida por el patrón estacional de la precipitación (Maass et al., 2002). La estación seca transcurre de diciembre a junio. El patrón estacional característico de lluvias del bosque tropical caducifolio (Rzedowski, 1978) o selva baja caducifolia (Miranda y Hernández-X, 1963), causa variaciones en los periodos fenológicos de la producción y caída de hojas por las plantas (Bullock y SolísMagallanes, 1990). Los cambios estacionales modifican la disponibilidad de luz y agua en el sotobosque y el suelo (Maass et al., 2002). La dispersión de semillas también ocurre durante la estación seca (Bullock y Solís-Magallanes, 1990) y las semillas remanentes en el reservorio de semillas del suelo aguardan el arribo del período de lluvias, que provee condiciones favorables para la germinación y establecimiento de las plántulas. El listado de la flora de la Estación de Biología en Chamela incluye 1120 especies en 544 géneros y 124 familias (Lott, 1993). En esta región, el ecosistema tropical estacional representa 47% del área total forestal, la cual ha tenido la mayor tasa de deforestación (Trejo y Dirzo, 2000). El principal factor de cambio de uso de la tierra es la ganadería extensiva donde se usa el fuego como herramienta de manejo de los pastos introducidos (Maass, 1995). MATERIALES Y MÉTODOS Selección de especies Las especies seleccionadas para el experimento fueron Caesalpinea platyloba S. Wats. (Leguminosae), llamada localmente acatizpa o coral, una especie maderable de lento crecimiento, propia Area of study The study was conducted in the region of Chamela, Jalisco, México. The coastal region of Jalisco is characterized by an irregular topography, with hilly terrains of 20 to 250 m that comprise numerous systems of small watersheds. The geology is represented by tertiary and quarternary igneous rocks (Cotler et al., 2002). The mean annual temperature is 21.4 °C. The average annual rainfall is 718 mm (350 to 1200 mm, interval) with 80% of the rainfall between July and November (García-Oliva et al., 2002). The dynamic of the ecosystem is controlled to a great extent by the seasonal pattern of rainfall (Maass et al., 2002). The dry season occurs from December to June. The characteristic seasonal pattern of rainfall of the tropical dry forest (Rzedowski, 1978) or low deciduous forest (Miranda and Hernández-X, 1963), causes variations in the phenological periods of the production and fall of leaves of the plants (Bullock and SolísMagallanes, 1990). The seasonal changes modify the availability of light and water in the understory and the soil (Maass et al., 2002). The dispersion of seeds also takes place during the dry season (Bullock and SolísMagallanes, 1990) and the remaining seeds in the seed reservoir of the soil await the onset of the rainy season, which provides favorable conditions for the germination and establishment of the seedlings. The list of flora of the Estación de Biología in Chamela includes 1120 species in 544 genera and 124 families (Lott, 1993). In this region, the seasonal tropical ecosystem represents 47% of the total forest area, which has suffered the highest rate of deforestation (Trejo and Dirzo, 2000). The principal factor of change in the use of the land is extensive cattle production where fire is used as a management tool of the introduced grasses (Maass, 1995). MATERIALS AND METHODS Selection of species The species that were selected for the experiment were Caesalpinea platyloba S. Wats. (Leguminosae), known locally as acatizpa or coral, a slow growing wood species, found in forests that are undisturbed or with almost no disturbance, with high demand in the regional market, and Spondias purpurea L. (Anacardiaceae), also known as Mexican plum (Mandujano, 2002), a fruit tree of fast growth found in rocky soils (Pimienta-Barrios and Ramírez-Hernández, 2003a; 2003b). Both species have a current demand and there is an interest in their cultivation and management on the part of the residents of the ejidos in the vicinity of Chamela, and they belong to two different functional groups in terms of growth. NAVA-CRUZ et al. 113 AGROCIENCIA, ENERO-FEBRERO 2007 de bosques sin alterar o con poca perturbación, con mucha demanda en el mercado regional, y Spondias purpurea L. (Anacardiaceae) también conocida como ciruelo (Mandujano, 2002), un frutal de rápido crecimiento que se encuentra en suelos rocosos (PimientaBarrios y Ramírez-Hernández, 2003a; 2003b). Ambas tienen demanda actual y un interés por su cultivo y manejo por los lugareños de los ejidos circundantes a Chamela, además de pertenecer a dos grupos funcionales diferentes en términos de su crecimiento. Los criterios de selección de especies consideradas incluyeron: importancia biológica (en términos de densidad, frecuencia y dominancia dentro de la comunidad), plasticidad (generalistas vs. especialistas), su aprovechamiento (forestal, medicinal, alimenticio, etc.), y disponibilidad de propágulos al inicio del estudio. Diseño experimental A mediados de la época de lluvias se trasplantaron 30 plántulas (8 meses de edad) de C. platyloba y 30 estacas de S. purpurea (30 cm de altura) en cada uno de 5 cuadrantes (5×50 m2) dispuestos en cada una de las dos parcelas experimentales constituidas por un fragmento remanente de BTC aledaño a una matriz de vegetación parántropica (potreros). Los cuadrantes se situaron en posición paralela al borde y a 0-5, 30-35 y 75-80 m del borde hacia el interior del bosque, y a 0-5 y 30-35 m hacia el potrero. Los individuos se distribuyeron en cada cuadrante usando un diseño aleatorio restringido. Es decir, el punto de implante se situó a una distancia mínima de 1 m respecto a los troncos de árboles adultos establecidos (DAP>5 cm), guardando una distancia de 1.5 m entre individuos. El trasplante incluyó un espacio de limpia en un radio de 1 m, para reducir el efecto de competencia. Las variables evaluadas fueron supervivencia y crecimiento (altura). El promedio de peso y diámetro basal inicial en las estacas de S. purpurea fue 101.7±37.2 g y 3.56±0.04 cm. Estos valores están dentro de la gama de tolerancia recomendada para la producción de plántulas por medio de estacas en viveros (Macía y Barfod, 2000). Muestreo de variables abióticas Con el objetivo de mostrar evidencias de los cambios abióticos en la zona de borde, se midieron las variables: 1) Diferencia entre la temperatura máxima y mínima del aire, medida a nivel del suelo de manera simultánea en el gradiente, usando termómetros de mercurio (precisión de 0.1 °C y con al menos 24 h de registro), 2) Radiación Fotosintéticamente Activa (RFA) a nivel del suelo, usando un ceptómetro (Delta T Devices) con 80 sensores de RFA a lo largo de una varilla de medición de 1m de longitud (4 lecturas en cada punto entre las 11 y las 13 h, en condiciones de luz directa); 3) indice de velocidad de infiltración de agua en el suelo, midiendo el tiempo de infiltración de 500 mL de agua vertidos en un cilindro de PVC (10 cm diámetro y 20 cm alto) insertado en el suelo a una profundidad de 5 cm (3 mediciones en cada punto de muestreo). El método de muestreo para estas variables consistió en realizar tres mediciones en puntos a lo largo de tres transectos perpendiculares al borde. Las mediciones dentro de cada transecto se hicieron en 114 VOLUMEN 41, NÚMERO 1 The criteria of species selection that were considered included: biological importance (in terms of density, frequency and dominance within the community), plasticity (generalists vs. specialists), use (forest, medicinal, food, etc.), and availability of propagules at the beginning of the study. Experimental design At the middle of the rainy season, 30 seedlings (8 months old) of C. platyloba were transplanted, along with 30 rootstocks of S. purpurea (30 cm height) in each of 5 quadrants (5×50 m2) located in the two experimental plots comprised of a remnant fragment of TDF next to a matrix of parantropic vegetation (paddocks). The quadrants were placed in position parallel to the edge and at 0-5, 30-35 and 75-80 m from the edge toward the inner forest, and at 05 and 30-35 m toward the paddock. The individuals were distributed in each quadrant in a restricted random design. That is, the planting point was located at a minimum distance of 1 m with respect to the trunks of established adult trees (CHD>5 cm), maintaining a distance of 1.5 m between individuals. The transplanting included a cleared space in a radius of 1 m, in order to reduce the effect of competition. The variables evaluated were survival and growth (height). The average of weight and initial basal diameter in the rootstocks of S. purpurea was 101.7±37.2 g and 3.56±0.04 cm. These values are within the range of tolerance recommendable for the production of seedlings from rootstocks in tree nurseries (Macía and Barfod, 2000). Sampling of abiotic variables With the objective of showing evidence of the abiotic changes in the edge zone, the following variables were measured: 1) Difference between maximum and minimum air temperature, measured at ground level simultaneously in the gradient, utilizing mercury thermometers (precision of 0.1 °C and with at least 24 h of registration), 2) Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR) at ground level, utilizing a septometer (Delta T Devices) with 80 sensors of PAR along a measuring bar 1 m in length (4 readings at each point between 11 and 13 h, under conditions of direct sunlight); 3) index of water infiltration velocity in the soil, measuring the time of infiltration of 500 mL of water poured into a PVC cylinder (10 cm diameter and 20 cm height) inserted in the soil at a depth of 5 cm (3 measurements at each sampling point). The sampling method for these variables consisted in taking three measurements at points along three transects perpendicular to the edge. The measurements within each transect were made at points located at 0, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40 and 80 m from the edge toward the inner forest, and at 1, 2.5, 5, 10 20 and 40 m from the edge toward the paddock, taking the edge as point 0. The location of the transects (within the 50 m width of the study plots) were determined randomly. The measurements were made in the rainy season and the dry season. EVALUACIÓN DEL EFECTO DE BORDE SOBRE DOS ESPECIES DEL BOSQUE TROPICAL CADUCIFOLIO DE JALISCO, MÉXICO puntos localizados a 0, 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40 y 80 m del borde hacia el interior del bosque, y a 1, 2.5, 5, 10, 20 y 40 m del borde hacia el potrero, tomando el borde como punto 0. La localización de los transectos (dentro de los 50 m de ancho de la parcelas de estudio) se determinó al azar. Las mediciones se hicieron en la época de lluvias y la época de secas. Análisis estadístico En el análisis de datos las variables de respuesta fueron la supervivencia y el crecimiento en altura. Los datos de supervivencia se analizaron como una variable de respuesta binaria (vivo o muerto) y se evaluaron usando un análisis de sobrevida (Méndez et al., 2004). El análisis incluyó dos factores: 2 parcelas×5 corredores en el gradiente potrero-bosque, y su interacción. La significancia fue estimada usando las pruebas Log-Rank y de Wilcoxon (p≤0.01). Los datos de crecimiento en altura se analizaron hasta el mes de mayo, por medio de un análisis de varianza, en un diseño de bloques completos al azar, tomando como covariable la altura inicial de cada planta. Los datos se analizaron con el programa JMP (2002). Al final del periodo de estiaje, diez meses después de iniciado el experimento (mayo 2000), las dos parcelas de estudio fueron expuestas a una quema accidental por los campesinos del lugar. La mayoría de las plantas, que hasta esa fecha habían sobrevivido en el potrero de ambas parcelas, murieron a causa del fuego. Por esta razón los análisis de sobrevida se hicieron censurando los datos: 1) hasta septiembre (todas las fechas) para ver el efecto de la quema, y 2) hasta mayo (con las fechas anteriores a la quema), para excluir su efecto, y 3) sólo con las plantas sembradas del borde hacia el interior del bosque en todas las fechas, ya que se observó que el fuego no sobrepasó los 10 m al interior del bosque. Para las variables abióticas se hizo un análisis de varianza anidado (JMP 2002). El análisis incluyó cuatro factores: época (2), parcela (2), transecto (3) y punto en el gradiente (14). En el análisis, los transectos se anidaron dentro de las parcelas. RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓN En la Figura 1 se muestran las modificaciones en las variables abióticas en la zona de borde, medidas a lo largo del gradiente selva/potrero. La infiltración del suelo es significativamente mayor en el bosque; la RFA y la diferencia de temperatura máxima y mínima del aire son significativamente mayores en el potrero. Después de cuatro meses de iniciado el experimento se observó una respuesta diferencial al gradiente microambiental entre las dos especies (χ2 en LogRank=519.593, p≤0.0001 y χ2 en Wilcoxon=441.082, p≤0.0001). En S. purpurea, cuatro meses después del trasplante su población había decrecido hasta 2% del total inicial; mientras que C. platyloba conservó más de 50% de sobrevivientes (Figura 2). La baja supervivencia de las plántulas de S. purpurea puede estar asociada a limitaciones ecológicas Statistical analysis In the data analysis survival and height growth were the response variables. The survival data were analized as a binary response variable (dead or alive) and were evaluated by means of a survival analysis (Méndez et al., 2004). The analysis consisted of two factors: 2 plots×5 corridors in the pasture-forest gradient, and their interaction. The significance was estimated using the Log-Rank and Wilcoxon test (p≤0.01). The data of height growth were analyzed until the month of May, by means of a variance analysis, in a design of completely randomized blocks, taking as covariable the initial height of each plant. The data were analyzed with the program JMP (2002). At the end of the dry period, ten months after the start of the experiment (May 2000), the two study plots were exposed to an accidental burning by the local farmers. Most of the plants, which until that time had survived in the pasture of both plots, died as a result of the fire. For this reason, the analyses of survival were made censuring the data: 1) until September (all of the dates) to see the effect of the fire, and 2) until May (with the dates prior to the fire), to exclude its effect, and 3) only with the plants sown from the edge toward the forest interior on all of the dates, as it was observed that the fire did not go beyond 10 m of the forest interior. For the abiotic variables, a nested analysis of variance was made (JMP 2002). The analysis included four factors: period (2), plot (2), transect (3) and point in the gradient (14). In the analysis, the transects were nested within the plots. RESULTS AD DISCUSSION The modifications in the abiotic variables in the edge zone, measured along the forest/paddok gradient are shown in Figure 1. Soil infiltration is significantly higher in the forest, and both the PAR and the difference of maximum and minimum air temperature are significantly higher in the paddock. Four months after the start of the experiment, a differential response to the micro-environmental gradient was observed between the two species (χ2 in LogRank=519.593, p≤0.0001 and χ2 in Wilcoxon= 441.082, p≤0.0001). In S. purpurea, four months after transplanting its population had decreased by as much as 2% of the initial total; whereas C. platyloba conserved more than 50% survivors (Figure 2). The low survival of the seedlings of S. purpurea could be associated to ecological limitations of the environment or to a deficient establishment. However, the fact that no significant differences were found in the survival of the rootstocks growing along the environmental gradient imposed by the edge effect, nor in that of the contrasting environment between the edge and the paddock, leads us to believe that the problem with the rootstocks from the start of the experiment was a homogeneously deficient establishment NAVA-CRUZ et al. 115 AGROCIENCIA, ENERO-FEBRERO 2007 116 VOLUMEN 41, NÚMERO 1 1.8 Índice de velocidad de infiltración 1.6 lt min−2 1.4 1.2 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 − 40 − 0.2 Lluvias Secas − 20 0 20 40 25 Diferencia de Temp. Max. Temp. Min. (°C) 80 60 Borde (m) − 0.4 Temperatura a nivel del suelo 20 15 10 5 0 −40 Lluvias Secas −20 1600 0 40 20 Borde (m) 60 80 Radiación fotosintética activa −1 MicroMol m−2 s del ambiente o a un establecimiento deficiente. Sin embargo, el hecho de no encontrar diferencias significativas en la supervivencia entre las estacas creciendo a lo largo del gradiente ambiental impuesto por efecto de borde, ni en lo referente al ambiente contrastante entre el bosque y el potrero, nos hace pensar que el problema con las estacas desde el inicio del experimento fue un establecimiento homogéneamente deficiente entre las estacas trasplantadas. Un estudio realizado en Cuba con estacas de 1 m de altura de S. purpurea (Alonso et al., 2001), mostró una supervivencia de 80% al año de haberse efectuado la plantación. Pimienta-Barrios y Ramírez-Hernández (2003a y 2003b) mostraron la eficacia en la capacidad de aclimatación a nivel fisiológico y estructural de S. purpurea en términos del contenido de clorofila y la conductancia estomática, las que variaron con la disponibilidad de la luz. En un análisis de la variación diurna en las tasas instantáneas de asimilación neta de CO2 y conductancia estomática, muestran que la ganancia de carbono en S. purpurea es alta, no obstante que la especie prospera en suelos pedregosos de baja fertilidad, con un manejo agronómico mínimo (Pimienta-Barrios y RamírezHernández, 2003a). Estos datos muestran la alta plasticidad que tiene S. purpurea para crecer en sitios con condiciones físicas extremas; sin embargo, en nuestro experimento no hubo un proceso óptimo de enraizamiento de las estacas trasplantadas. La tasa de supervivencia para C. platyloba fue mucho mayor a la de S. purpurea. Ésto seguramente se debió no sólo a diferencias en la fisiología de la especie, sino también al hecho de que para C. platyloba se transplantó plántulas ya desarrolladas (raíz, tallo y hojas), a diferencia de las estacas de S. purpurea que, suponemos, carecían de suficiente masa radical para su establecimiento. C. platyloba muestra que el porcentaje de supervivencia varía significativamente (χ2 en LogRank=45.819, p≤0.0001 y χ2 en Wilcoxon=45.950, p≤0.0001) en razón a su posición con respecto al borde (Figura 3). El análisis hecho con todas las fechas y los cinco corredores evidencia una mayor supervivencia en los corredores del interior del bosque y, además, un decremento significativo de la supervivencia en mayo por el efecto de quema mencionado en los métodos. Sin embargo, la diferencia de la supervivencia entre los corredores del interior del bosque no es significativa (χ2 en Log-Rank=11.292, p=0.023 y χ2 en Wilcoxon=12.120, p=0.016). Es clara la diferencia en la supervivencia entre las plántulas creciendo en el potrero y aquellas creciendo en el interior del bosque (Figura 3). Se ha discutido que la disponibilidad de agua limita la supervivencia y crecimiento de las plantas del BTC (Holbrook et al., 1995). Además, se Lluvias Secas 1200 800 400 0 − 40 − 20 0 40 20 Borde (m) 60 80 Figura 1. Evidencias del efecto de borde sobre algunas variables del ambiente físico en las parcelas de estudio. Figure 1. Evidences of the edge effect on some variables of the physical environment in the experimental plots. among the transplanted rootstocks. A study conducted in Cuba with rootstocks of 1 m height of S. purpurea (Alonso et al., 2001), showed a survival of 80% a year after planting. Pimienta-Barrios and Ramírez-Hernández (2003a and 2003b) showed the effectiveness in the acclimation capacity at the physiological and structural level of S. purpurea in terms of chlorophyll content and stomatic conduction, which varied with light availability. In an EVALUACIÓN DEL EFECTO DE BORDE SOBRE DOS ESPECIES DEL BOSQUE TROPICAL CADUCIFOLIO DE JALISCO, MÉXICO 1.0 Caes Spond 0.9 Supervivencia 0.8 0.7 Efecto de la quema 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mes 9 10 11 12 13 14 Figura 2. Supervivencia de S. pupurea y C. platyloba a 14 meses de su trasplante a las parcelas de estudio. Figure 2. Survival of S. purpurea and C. platyloba 14 months after transplanting to the experimental plots. 1.0 0.9 Supervivencia 0.8 Efecto de la quema 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 P40 P5 B30 B5 B80 0.2 0.1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mes 9 10 11 12 13 14 Figura 3. Supervivencia de C. platyloba en los cinco corredores de las dos parcelas de estudio. Figure 3. Survival of C. platyloba in the five corridors of the two experimental plots. ha mencionado que la erosión en el suelo de los potreros modifica, en gran medida, su capacidad de infiltración y retención de agua, así como el ciclo de nutrimentos en comparación con el suelo del bosque (Maass, 1995). Como se muestra en la Figura 1, hacia el interior de la selva las condiciones ambientales son más propicias para el desarrollo de las plántulas. En los bosques secos, donde la evapotranspiración potencial supera la precipitación, la cantidad de agua en el sistema puede condicionar el establecimiento y desarrollo de la vegetación. Los datos de supervivencia de C. platyloba muestran diferencias significativas en términos de los dos ambientes contrastantes (potrero y bosque), aunque Huante y Rincón (1998) la describen como una especie con una amplia plasticidad en ambientes contrastantes de luz. Sin embargo la luz no es el único factor modi- analysis of the daily variation of the instant net assimilation of CO2 and stomatic conduction, it is shown that the carbon gain in S. purpurea is high, despite the fact that the species prospers in rocky soils of low fertility, with a minimum agronomic management (Pimienta-Barrios and RamírezHernández, 2003a). These data show the high plasticity that S. purpurea has for growing in sites with extreme physical conditions; however, in our experiment, the rooting process of the transplanted rootstocks was not optimum. The survival rate for C. platyloba was much higher than that of S. purpurea. This was due not only to differences in the physiology of the species, but also to the fact that for C. platyloba, seedlings that were already developed (root, stem and leaves) were transplanted, unlike the case of the rootstocks of S. purpurea, which, we assume, lacked sufficient root mass for their establishment. C. platyloba shows that the percentage of survival varied significantly (χ2 in Log-Rank= 45.819, p≤0.0001 and χ2 in Wilcoxon=45.950, p≤0.0001) due to its position with respect to the edge (Figure 3). The analysis made with all of the dates and the five corridors shows a higher survival in the corridors of the forest interior and, besides, a significant decrease of survival in May as a result of the burning mentioned in the methods. However, the difference of the survival among the corridors of the inner forest is not significant (χ2 in Log-Rank=11.292, p=0.023 and χ2 in Wilcoxon =12.120, p=0.016). The difference is clear in the survival between the seedlings growing in the paddock and those growing in the inner forest (Figure 3). It has been discussed that the availability of water limits the survival and growth of the plants of the TDF (Holbrook et al., 1995). Besides, it has been mentioned that the erosion in the soil of the paddock modifies to a large degree its capacity of water infiltration and retention, as well as the nutrient cycle, compared to the soil of the forest (Maass, 1995). As is shown in Figure 1, toward the inner forest the environmental conditions are more suitable for the development of the seedlings. In the dry forests, where the potential evapotranspiration surpasses precipitation, the amount of water in the system can condition the establishment and development of the vegetation. The data of survival of C. platyloba show significant differences in terms of the two contrasting environments (paddock and forest), although Huante and Rincón (1998) describe it as a species with an ample plasticity in contrasting environments of light. However, light is not the only factor that is modified in the gradient between the paddock and the inner forest; the high temperature and low availability of water can also be NAVA-CRUZ et al. 117 AGROCIENCIA, ENERO-FEBRERO 2007 CONCLUSIONES Los factores del ambiente influyen de manera diferencial en las especies, particularmente en su supervivencia. 118 VOLUMEN 41, NÚMERO 1 determining factors of stress for the seedlings in the paddock (Figure 1). Given the great heterogeneity in the diversity and structure of the TDF, it is not surprising that our results show a clear effect of site in terms of the survival and height growth of C. platyloba (Figures 4 and 5). It is pertinent to mention that field observations made in the two experimental plots indicate that Plot 2 has a soil that is deeper and less rocky, as well as a higher canopy and a thicker layer of humus compared with Plot 1. The fact that significant differences (χ2 in LogRank=523.881, p≤0.0001 and χ2 in Wilcoxon= 445.640, p≤0.0001) were found in the survival of C. platyloba in the two experimental plots (Figure 4), show that in an environment that is as heterogeneous 1.0 0.9 Parcela 1 Parcela 2 Supervivencia 0.8 0.7 0.6 0.5 0.4 0.3 0.2 0.1 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Mes 9 10 11 12 13 14 Figura 4. Supervivencia de C. platyloba en las dos parcelas de estudio. Figure 4. Survival of C. platyloba in the two experimental plots. 30 Parcela 1 Parcela 2 25 Altura promedio (cm) ficado en el gradiente entre el potrero y el interior del bosque; la alta temperatura y la baja disponibilidad de agua pueden ser también factores determinantes del estrés para las plántulas en el potrero (Figura 1). Dada la gran heterogeneidad en la diversidad y estructura del BTS, no sorprende que nuestros resultados evidencien un claro efecto de sitio en términos de la supervivencia y el crecimiento en altura de C. platyloba (Figuras 4 y 5). Es pertinente mencionar que observaciones de campo realizadas en las dos parcelas de estudio indican que la Parcela 2 tiene un suelo más profundo y menos pedregoso, así como un dosel más alto y una capa más gruesa de mantillo, comparada con la Parcela 1. El hecho de encontrar diferencias significativas (χ2 en Log-Rank=523.881, p≤0.0001 y χ2 en Wilcoxon=445.640, p≤0.0001) en la supervivencia de C. platyloba en las dos parcelas experimentales (Figura 4), evidencia que en un ambiente tan heterogéneo como el BTC, donde la vegetación está adaptada a las enormes variaciones que impone un ambiente marcadamente estacional, el efecto de sitio puede llegar a enmascarar el del gradiente ambiental (Figura 1) generado por la creación del borde. El análisis de varianza del aumento relativo en altura para C. platyloba mostró diferencias entre los sitios de estudio y entre las plántulas que crecen en los potreros respecto a aquellas que lo hacen en el bosque (efecto de la interacción distancia*parcela F=15.831, p≤0.0001). Las plántulas que sobrevivieron en el protero de la parcela 1 tuvieron una respuesta muy favorable en crecimiento (Figura 5). Al parecer, las plántulas que sobreviven al periodo de sequía son favorecidas por la combinación entre el periodo de lluvias y la disponibilidad de un ambiente lumínico más homogéneo que proveen los pastos a diferencia de las plántulas del bosque, donde la competencia por recursos está presente aún en el periodo de mayor humedad. El uso del fuego como herramienta de manejo de la matriz antropógena en la que se encuentran inmersos los parches de BTC en la región, es una limitación en la gestión de iniciativas de manejo orientadas a la rehabilitación del ecosistema natural. El tipo de cobertura vegetal adyacente a los fragmentos de bosque genera un borde abrupto poco permeable al flujo de semillas y propágulos a través de sus dispersores (Cadenasso y Pickett, 2001; Gascon et al., 2000) pero, además, las quemas frecuentes afectan el reservorio de semillas y merman el desarrollo de las plántulas establecidas en las inmediaciones de los fragmentos. 20 15 10 5 0 P40 P5 B5 Corredor B40 B80 Figura 5. Crecimiento en altura de C. platyloba después de 14 meses del trasplante en las dos parcelas de estudio (P=Potrero, B=Bosque; los números indican la distancia en metros desde el borde). Figure 5. Height growth of C. platyloba 14 months after transplanting in the two experimental plots (P= paddock, F=Forest; the numbers indicate the distance in meters from the edge). EVALUACIÓN DEL EFECTO DE BORDE SOBRE DOS ESPECIES DEL BOSQUE TROPICAL CADUCIFOLIO DE JALISCO, MÉXICO La baja supervivencia de las plántulas de S. purpurea en nuestro experimento puede estar asociada a limitaciones ecológicas del ambiente o a un deficiente proceso de establecimiento de las estacas. En un ambiente tan heterogéneo como el BTC, el efecto de sitio puede enmascarar el efecto del gradiente ambiental generado por la creación de bordes. El uso del fuego como herramienta de manejo pone en riesgo las parcelas donde pudiera establecerse un tipo de manejo alternativo a la ganadería. Pero, además, su efecto paulatino está afectando las zonas limítrofes entre los potreros y los fragmentos remanentes de selva, así como la posible recuperación de los potreros en desuso. AGRADECIMIENTOS Los autores expresamos nuestro agradecimiento a Julieta Benítez, a Martin Ricker y a los tres evaluadores anónimos por la revisión del manuscrito. A René Martínez-Bravo, Salvador Araiza, Abel Verduzco y Raúl Ahedo por su apoyo técnico. Agradecemos al personal de la Estación de Biología Chamela por su apoyo logístico, y al ejidatario Sr. Ramiro Peña, de San Mateo, Jalisco. Asimismo, agradecemos al Vivero Forestal de Tomatlán de donde se obtuvieron las plántulas utilizadas en el estudio. El proyecto recibió financiamiento de la UNAM (PAPIIT-DGAPA) y del CONACyT, México. LITERATURA CITADA Alonso, J., G. Febles, T. E. Ruiz, y J. C. Gutiérrez. 2001. Fecha de plantación para el establecimiento de árboles como cercas vivas en área de pastoreo. Rev. Cub. Ciencia Agríc. 35(2): 183187 Benítez-Malvido, J., and M. Martínez-Ramos. 2003 a. Impact of forest fragmentation on understory plant species richness in Amazonia. Conservation Biol. 17: 598-606. Benítez-Malvido, J., and M. Martínez-Ramos. 2003 b. Influence of edge exposure on seedling species richness in tropical rainforest fragments. Biotropica 35: 530-541. Bullock, S. H., and A. Solís-Magallanes. 1990. Phenology of canopy trees of a tropical deciduous forest in Mexico. Biotropica 22(1): 270-274. Cadenasso, M. L., and S. T. Pickett. 2001. Effect of edge structure on the flux of species into forest interiors. Conservation Biol. 15: 91-97. Camargo, J. L., and V. Kapos. 1995. Complex edge effects on soil moisture and microclimate in central Amazonian forest. J. Trop. Ecol. 11: 205-221. Cotler, H., E. Durán, y C. Siebe. 2002. Caracterización morfoedafológica y calidad de sitio de un bosque tropical caducifolio. In: Noguera, F.A., J.H. Vega Ribera, A.N. García Aldrete y M. Quezada (eds). Historia Natural de Chamela. Instituto de Biología, UNAM. México. D.F. pp: 17-79. García-Oliva F., A. Camou, y M. Maass. 2002. El clima de la región central de la costa del Pacífico mexicano. In: Noguera, F. A., J. H. Vega Ribera, A.N. García Aldrete y M. Quezada (eds.). Historia Natural de Chamela. Instituto de Biología, UNAM. México. D.F. pp: 3-10. as the TDF, where the vegetation is adapted to the enormous variations imposed by a markedly seasonal environment, the effect of site can even mask that of environmental gradient (Figure 1) generated by the creation of the edge. The analysis of variance of the relative increase in height for C. platyloba showed differences among the experimental sites and among the seedlings that grow in the paddock with respect to those that grow in the forest (effect of the interaction distance*plot F=15.831, p≤0.0001). The seedlings that survived in the pasture of plot 1 had a very favorable response in growth (Figure 5). Apparently, the seedlings that survive the dry period are favored by the combination between the rainy period and the availability of a more homogeneous luminous environment provided by the pastures, contrary to the seedlings of the forest, where competition for resources is present even in the period of greatest moisture. The use of fire as a management tool of the anthropogenic matrix where the patches of TDF in the region are immersed, is a limitation in the promotion of management initiatives oriented towards the rehabilitation of the natural ecosystem. The type of plant cover adjacent to the forest fragments generates an abrupt edge that is nearly impermeable to the flux of seeds and propagules from their dispersers (Cadenasso and Pickett, 2001; Gascon et al., 2000), but also, frequent burnings affect the seed reservoir and reduce the development of the seedlings established in the vicinity of the fragments. CONCLUSIONS The environmental factors have a differential influence on the species, especially with respect to survival. The low survival of seedlings of S. purpurea in our experiment could be associated to ecological limitations of the environment or to a deficient process of establishment of the rootstocks. In an environment as heterogeneous as the TDF, the effect of site can mask the effect of environmental gradient generated by the creation of edges. The use of fire as a management tool puts at risk the plots where a type of management other than that of cattle production could be established. But also its gradual effect is influencing the border zones between the pastures and the remnant forest fragments, as well as the possible recuperation of the unused paddocks. —End of the English version— NAVA-CRUZ et al. 119 AGROCIENCIA, ENERO-FEBRERO 2007 Gascon, C., G. B. Williamson, and G. A. Da Fonseca. 2000. Receding forest edges and vanishing reserves. Science 288: 13561358. Harris, L.D. 1998. Edge effects and conservation of biotic diversity. Conservation Biol. 2: 330-332. Holbrook, M. N., J. L., Whitbeck, and H. A., Mooney, 1995. Drought responses of neotropical dry forest trees. In: Bullock, S. H., H. A., Mooney, and E. Medina. (eds). Seasonally Dry Tropical forests. Cambridge University Press, New York. pp: 243–270. Huante P., and E. Rincón, 1998. Responses to light changes in tropical deciduous woody seedlings with contrasting growth rates. Oecologia 113: 53-66. JMP. 2002. JMP® Statistics and Graphics Guide, Version 5. Cary, N.C. SAS Institute. pp: 315–334. López-Barreda, F. 2004. Estructura y función en bordes de bosques. Ecosistemas. http//www.aeet.org/ecosistemas/041/revision1.htm). Diciembre de 2006. Lott, E. J. 1993. Annotated checklist of the vascular flora of the Chamela Bay Region, Jalisco, México. Occasional Papers of the California Academy of Sciences 148: 1-60. Maass, J. M. 1995. Conversion of tropical dry forest to pasture and agriculture. In: Bullock, S. H., H. A. Mooney and E. Medina (eds.). Seasonally Dry Tropical Forest. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. 450 p. Maass, J. M., V. Jaramillo, A. Martínez-Yrízar, F. García-Oliva, A. Pérez-Jiménez, y J. Sarukhán. 2002. Aspectos funcionales del ecosistema de selva baja caducifolia en Chamela, Jalisco. 120 VOLUMEN 41, NÚMERO 1 In: Noguera, F. A., J. H. Vega Ribera, A. N. García Aldrete y M. Quezada (eds). Historia Natural de Chamela. Instituto de Biología, UNAM. México, D.F. pp: 525-542. Macía, M., and A. S. Barfod. 2000. Cultivation, management and economic botany of ovo (Spondias purpurea L.) in Ecuador. Economic Bot. 54(4): 449-458, Mandujano, S. 2002. Spondias purpurea L. (Anacardiaceae). Ciruelo. In: Noguera, F. A., J. H. Vega Ribera, A. N. García Aldrete y M. Quezada (eds.). Historia Natural de Chamela. Instituto de Biología, UNAM. México, D.F. pp: 145-150. Méndez, I., N. Guerrero, L. Moreno, y C. Sosa. 2004. El Protocolo de Investigación: Lineamientos para su Elaboración y Análisis. Ed. Trillas. México. D. F. 210 p. Miranda, F. G., y E. Hernández-X. 1963. Los tipos de vegetación de México y su clasificación. Bol. Soc. Bot. Méx. 28:29–176. Pimienta-Barrios, E., and B. C. Ramírez-Hernández. 2003 a. Phenology, growth, and response to light of ciruela mexicana (Spondias purpurea L., Anacardiaceae). Econ. Bot. y 57(4): 481-490. Pimienta-Barrios, E., and B. C. Ramírez-Hernández. 2003 b. Photosynthesis in Mexican plum [Spondias purpurea L. (Anacardiaceae)]. Rev. Chapingo 9(2): 271-277. Rzedowski, J. 1978. Vegetación de México. Limusa, México. 432 p. Trejo, I., and R. Dirzo. 2000. Deforestation of seasonally dry tropical forest-A national and local analysis in México. Biol. Conservation 94(2):113-142. William, F. L. 2002. Hyperdynamism in fragmented habitats. J. Veg. Sci. 13:595-602.