Alliance of Civilizations International Security and Cosmopolitan

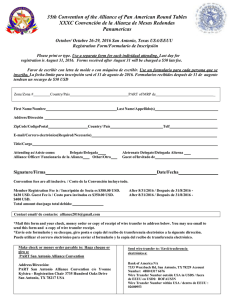

Anuncio