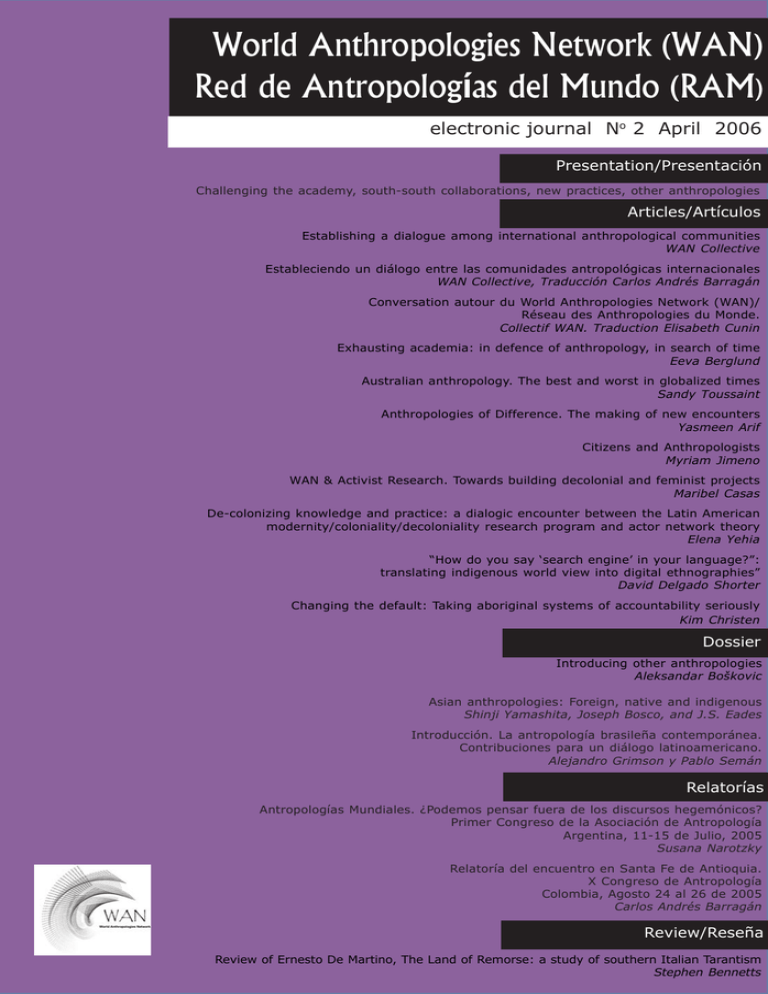

World Anthropologies Network (WAN) Red de - Ram-Wan

Anuncio