Interests and identities in the enlarged EU: A re-assessment

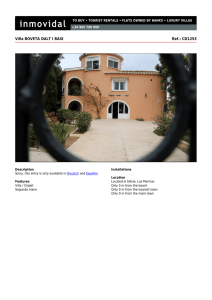

Anuncio