Big Sur Voice - STUDIO CARVER ARCHITECTS

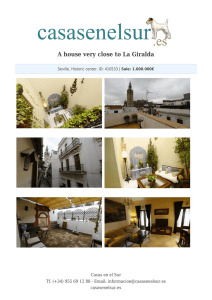

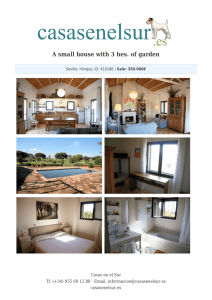

Anuncio