The Judges` Newsletter Boletín de los jueces

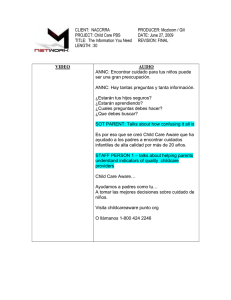

Anuncio