Crime and Punishment

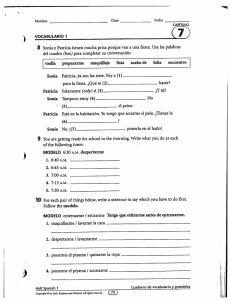

Anuncio