ANALYZING THE RELATIONS AMONG PERCEIVED

Anuncio

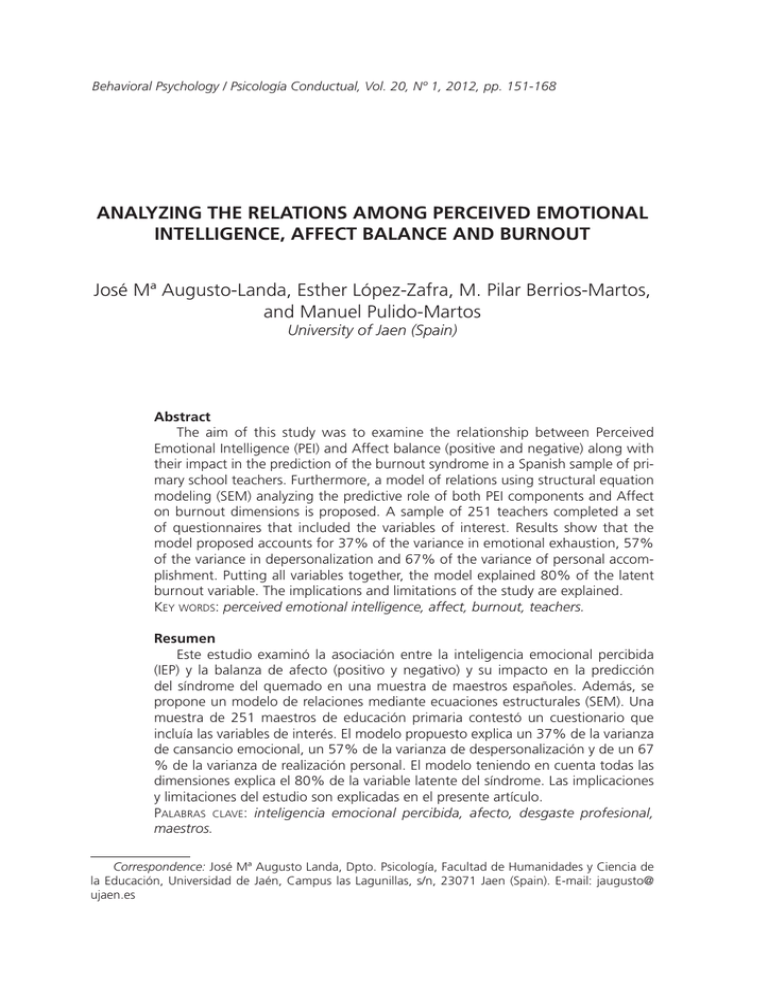

Behavioral Psychology / Psicología Conductual, Vol. 20, Nº 1, 2012, pp. 151-168 ANALYZING THE RELATIONS AMONG PERCEIVED EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE, AFFECT BALANCE AND BURNOUT José Mª Augusto-Landa, Esther López-Zafra, M. Pilar Berrios-Martos, and Manuel Pulido-Martos University of Jaen (Spain) Abstract The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between Perceived Emotional Intelligence (PEI) and Affect balance (positive and negative) along with their impact in the prediction of the burnout syndrome in a Spanish sample of primary school teachers. Furthermore, a model of relations using structural equation modeling (SEM) analyzing the predictive role of both PEI components and Affect on burnout dimensions is proposed. A sample of 251 teachers completed a set of questionnaires that included the variables of interest. Results show that the model proposed accounts for 37% of the variance in emotional exhaustion, 57% of the variance in depersonalization and 67% of the variance of personal accomplishment. Putting all variables together, the model explained 80% of the latent burnout variable. The implications and limitations of the study are explained. Key words: perceived emotional intelligence, affect, burnout, teachers. Resumen Este estudio examinó la asociación entre la inteligencia emocional percibida (IEP) y la balanza de afecto (positivo y negativo) y su impacto en la predicción del síndrome del quemado en una muestra de maestros españoles. Además, se propone un modelo de relaciones mediante ecuaciones estructurales (SEM). Una muestra de 251 maestros de educación primaria contestó un cuestionario que incluía las variables de interés. El modelo propuesto explica un 37% de la varianza de cansancio emocional, un 57% de la varianza de despersonalización y de un 67 % de la varianza de realización personal. El modelo teniendo en cuenta todas las dimensiones explica el 80% de la variable latente del síndrome. Las implicaciones y limitaciones del estudio son explicadas en el presente artículo. Palabras clave: inteligencia emocional percibida, afecto, desgaste profesional, maestros. Correspondence: José Mª Augusto Landa, Dpto. Psicología, Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencia de la Educación, Universidad de Jaén, Campus las Lagunillas, s/n, 23071 Jaen (Spain). E-mail: jaugusto@ ujaen.es 152 Augusto-Landa, López-Zafra, Berrios-Martos, and Pulido-Martos Introduction The burnout syndrome is one of the main psychosocial risks to which workers are exposed today. This syndrome refers to the fact that a professional may be overwhelmed by the working context, and that his/her capacity for adaptation has been exceeded. The concept of burnout was firstly mentioned by Freudenberger (1974) to describe the physical and mental state that he observed among young volunteers working in a detox clinic. After a year they felt exhausted, were easily irritated, had developed a cynical attitude towards their patients and tended to avoid them. Afterwards, Maslach (1977) used the term at an APA (American Psychology Association) convention. Since then, this term is used to describe the burnout experienced by workers in human services (education, health, and public administration) (Salanova, Schaufeli, Llorens, Peiró, & Grau, 2000). Specifically, Maslach (1993) define burnout as a psychological syndrome of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and reduced personal accomplishment that may appear in normal individuals who work with people in some way. Emotional exhaustion (EE) refers to feelings of not being able to give more of themselves on an emotional level and a decrease in the emotional resources (progressive tiredness, fatigue or loss of energy). Depersonalization (D) refers to the development of feelings, attitudes, and negative responses (both distant and cold) to other people, especially to the beneficiaries of their work. Lack of personal accomplishment (PAC) refers to negative evaluation that the individual makes about him/her-self competence and their performance at work. Regardless of educational level, teachers experience daily demands and working conditions that imply a high emotional involvement (Martínez, Grau, & Salanova, 2002) which may provoke the appearance of burnout among these professionals (Friedman, 2000; Jennett, Harris, & Mesibov, 2003; Manassero, Vázques, Ferrer, Fornés, & Fernández, 2003; Mota-Cardoso, Araujo, Ramos, Gonçalves, & Ramos, 2002; Vandenberghe & Huberman, 1999). Among the burnout triggers are: work overload (Antoniou, Polychroni, & Vlachakis, 2006), role conflict (Burke, Greenglass, & Schwarzer, 1996), role ambiguity (Kokkinos, 2007), conflicts, relationships and students´ behavior (Betoret, 2006; Carlotto, 2002; Hakanen, Bakker, & Schaufeli, 2005), conflicts with other teachers (Skaalvik & Skaalvik, 2007) or lack of social support (Marqués-Pinto, Lima, & Lopes da Silva, 2005). There are good reasons for the increased research interest on teacher’s burnout, due to the serious consequences it may have for teachers regarding their welfare, their teaching profession, and the results of their student´s learning. In particular, teacher burnout may jeopardize the quality of teaching, and could also lead to job dissatisfaction, work alienation; physical and emotional poor health and teachers giving up their profession (see Vandenberghe & Huberman, 1999 or Schaufeli, 2005 for a review). The interest in knowing the personal variables that influence this syndrome and its associated symptoms has increased over time (Brock & Grady, 2002; Extremera, Rey, & Pena, 2010; Van Horn, Schaufeli, Greenglass, & Burke, 1997). Evidence suggests the existence of personality factors and emotional skills Perceived emotional intelligence, affect balance and burnout 153 that influence the overall levels of teacher stress, even when controlling for organizational typically stressors and work environment (e.g. work overload, lack of resources, insufficient salary, lack of professional recognition...) (Mearns & Cain, 2003). On the following, we discuss about some personality and emotional factors. Positive affect versus negative affect Most studies about the affect structure agree that affect is compound by two dimensions namely positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA) (Diener, Larsen, Levine, & Emmons, 1985; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988; Zevon & Tellegen, 1982). Positive affect reflects the positive emotions, energy, affiliation and control of an individual. Thus, individuals with high scores on PA experience more easily feelings of satisfaction, enthusiasm, energy, friendship, affirmation, union and trust. Instead, people who score low in PA tend to show disinterest and boredom (Clark, Watson, & Mineka, 1994). On the contrary, NA represents a general dimension of subjective distress, and an unpleasant feeling including a variety of aversive emotional states such as disgust, anger, guilt, fear and nervousness (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988), negative attitudes and pessimism (Watson & Clark, 1997), somatic problems (Clark, Beck, & Stewart, 1990) and negative evaluation of oneself and others (Gara et al., 1993). As suggested by Sandín et al. (1999), these two dimensions may be conceptualized as affective states or more or less stable personal emotional dispositions. In this sense, results show correspondence between NA and neuroticism whereas PA relates to extraversion (Clark et al., 1994). Studies about teachers have found that they experience more frequently negative than positive emotions (Emmer, 1994). Negative emotions such as anxiety interfere with the cognitive ability to process information (Eyseck & Calvo, 1992), whereas positive emotions increase the capacity to cope with difficulties (Frederickson, 2001). Studies with primary school teachers relating burnout and personality variables have shown that neuroticism is one of the components that best predict the dimensions of burnout. Thus, neuroticism shows positive relations with emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and negative relations with personal accomplishment (Cano-García, Padilla-Muñoz, & Carrasco-Ortiz, 2005; Kokkinos, 2007). As Fernández-Berrocal and Ruiz-Aranda (2008) suggest, teachers that learn how to maintain positive emotional states and reduce the negative ones, will achieve greater welfare for themselves and also students would benefit with a better fit. Several studies have addressed the role of the affect balance of stress and burnout. Thus, Moya-Albiol, Serrano, GonzálezBaro, Rodríguez-Alarcon and Salvador (2005) measured psychophysiological responses (emotional, hormonal and cardiovascular) in a working day and in a free day in a group of teachers. Results show that both negative and positive affect scores are greater during the working day. These results suggest there is a greater activation with the consequent state of alert, explained by the increased positive mood, whereas an increased subjective distress and unpleasant emotional states would explain the greater negative mood. Thus, the two PA and NA scores reflect 154 Augusto-Landa, López-Zafra, Berrios-Martos, and Pulido-Martos different aspects, as the positive mood state would reflect a cognitive state, while the negative would reflect an emotional state. Therefore, daily work would worsen the negative mood and increase subjective perception of stress in teachers. Zellars, Hochwater, Perrewé, Hoffman and Ford (2004) analyzed the predictive ability of emotional balance on the components of burnout. Their results showed that negative affect was a predictor of emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, while positive affect predicted of personal accomplishment. The study by Kluemper, Little and De Groot (2009) found negative relationships between positive affect, burnout and physical symptoms. However, these relationships were positive in job satisfaction and task performance. On the contrary, negative affect yielded positive relationships with distress and burnout, and negative with job satisfaction and task performance. Perceived emotional intelligence The concept of emotional intelligence (EI) proposed by Mayer and Salovey (1997) refers to a genuine intelligence in adaptive use of our emotions, implying that the subject can solve problems and adapt effectively to the environment. Emotional intelligence is conceived as a hierarchical structure compound by four basic abilities: 1) ability to perceive emotions adequately; implies the perception of one´s own and other´s emotions along with the ability to express and correctly assess our feelings and needs (emotional perception); 2) ability to elicit emotions that facilitate thinking (emotional facilitation); 3) ability to understand emotions, the relationships between them and to emotionally reasoning (emotional understanding); and 4) ability to regulate the emotions of one-self and other’s in the right way promoting emotional and intellectual improving (emotional management). These abilities are on a sequence from the most basic psychological processes (emotional perception) to the most complex (emotional management). The most widely used self-report to measure EI has been the Trait Meta-Mood Scale (TMMS) that assess the perceived emotional intelligence (PEI), or the metaknowledge that individuals have about their own emotional abilities (Salovey, Stroud, Woolery, & Epel, 1995). Thus, it refers to the subjects´ beliefs about their own capacities for attention, clarity and intra-personal emotional regulation. Research has found PEI to be a significant predictor of social and personal functioning of the individual (eg. quality of life, Augusto Landa, Lopez-Zafra, Martínez de Antoñana, & Pulido, 2006; anxiety and depression, Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2006; happiness, Augusto, Pulido, & Lopez-Zafra, 2011a; Extremera, Salguero, & FernándezBerrocal, 2011); health, Augusto, Pulido, & Lopez-Zafra, 2011b; Martins, Ramalho, & Morin, 2010, or empathy, Aguilar-Luzón & Augusto Landa, 2009, among others). Thus, PEI would explain how some people are more resistant to stressors due to their ability to perceive, understand and regulate their emotions. Studies in the field of occupational stress have found that workers with higher emotional skills report lower levels of burnout in nursing (Augusto Landa, Lopez-Zafra, Berrios Martos, & Aguilar Luzón, 2008; Limonero, Gómez-Benito, Tómas-Sabato, & Fernández- Perceived emotional intelligence, affect balance and burnout 155 Castro, 2004); in graduate students (Extremera, Durán, & Rey, 2007); or in workers with people intellectually disable (Durán, Extremera, & Rey, 2004). Research that focus on the analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and personal adjustment agrees that EI predicts the level of teacher burnout. The study by Extremera, Fernández-Berrocal and Duran (2003) with secondary school teachers found that emotional repair (in a negative sense) accounted for the 3% of the emotional exhaustion variance and for the 3% of the emotional depersonalization whereas personal accomplishment was accounted for the 10% by emotional repair and for the 2% by emotional clarity. In sum, subjects who are able to understand their emotional states and to prolong positive emotions while reducing negative emotional states, report lower levels of burnout. Similarly, Extremera, Durán and Rey (2010) analyzed the predictive role of self-esteem, self-efficacy and PEI on burnout. Their findings showed that 7.6% of the variance in emotional exhaustion accounted for by emotional attention (in a positive sense) and emotional clarity (in a negative sense). Emotional clarity accounted for the 8.4% of the variance for depersonalization (in a negative direction). Emotional clarity accounted for the 4% of personal accomplishment variance (in a positive direction). Thus, these findings underscore the importance of low levels of emotional attention and a good intrapersonal emotional clarity as personal resources relevant to the prevention of the burnout syndrome. Recently, Platsidou (2010) in a study carried out with Greek special education teachers using the Emotional Intelligence Scale (EIS; Schutte et al., 1998) found that emotional repair predicted the personal accomplishment. Specifically, teachers with a high emotional repair report a high personal accomplishment in their work. Also recently, Pena and Extremera (in press) analyzed, using Wong and Law´s instrument (WLEIS, 2002), the impact of EI on the burnout dimensions and engagement in primary school teachers. Regression analyses showed that emotional assimilation, that is, taking into account the feelings when reasoning or solving problems, helps us to focusing our attention on the relevant aspects to face a particular situation, was the most important aspect in predicting the dimensions of burnout and engagement. Interpersonal attention (the ability to properly identify the emotions of others and discriminate the sincerity of the emotions expressed by others) predicted (at a negative level) the dimension of depersonalization. Finally, emotional repair predicted the components of engagement. Brackett, Palomera, Mojsa, Reyes and Salovey (2010) propose, using structural equation modeling, a model explaining the impact of EI on burnout dimensions in a sample of secondary school teachers. Taking into account the emotional repair dimension of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT, 2002), and the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS, Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) they showed the impact of these dimensions on burnout and work satisfaction. Emotional repair predicted personal accomplishment and also mediated the influence of positive affect. In nursing professionals, Augusto-Landa, BerriosMartos, Lopez-Zafra and Aguilar-Luzon (2006) showed that the components of PEI predicted the dimensions of burnout when controlling the balance of affects. Specifically, emotional attention accounted for (in a positive sense) the 9% of emo- 156 Augusto-Landa, López-Zafra, Berrios-Martos, and Pulido-Martos Figure 1 Hypothesized theoretical model tional exhaustion and for the 10% of despersonalization. Likewise, the attention (negatively) and the clarity and emotional repair (positively) accounted for 41% of the variance of personal accomplishment. Similar results were found by Extremera, Fernández-Berrocal and Durán (2003) and Durán, Extremera and Rey (2004). Based on the above findings, our main objectives were to analyze the joint influence of the components of the PEI on all the dimensions of burnout and to propose a model that includes positive affect as a mediating variable as the reviewed literature suggests. Our predictions are covered by the model in figure 1. In summary, we propose that the three dimensions of the PEI influence on burnout (as reported in the model as a latent variable) through positive affect. Secondly, negative affect is expected to account for the burnout variance. Specifically, we expect NA to explain emotional exhaustion, depersonalization (at a positive level) and personal accomplishment (at a negative level). Thirdly, we expect positive relationships between emotional attention and emotional clarity, and between clarity and emotional repair. Finally, we do not establish relationships between the dimensions of the IEP to avoid problems of under-identification of the hypothesized model. Method Participants Two hundred and fifty-one primary school teachers (64.5% women; age M= 39; SD= 11.25; range= 22 to 60 years old) from nine public schools in Spain participated in this study1. As for the roles performed by the teachers, 86% dealt with 1 This study is part of a wider research with primary schools teachers. Other results related to other variables with this sample are included in Augusto Landa, López-Zafra, & Pulido, 2011). Perceived emotional intelligence, affect balance and burnout 157 teaching duties, 4% had administrative dedication and the rest combined both functions in the development of their tasks. Instruments 1. Trait Meta Mood Scale (TMMS; Salovey, Mayer, Goldman, Turvey, & Palfai, 1995). On 5-point scales, participants evaluated their emotional intelligence. We used the Spanish version of the reduced version of TMMS (Fernández-Berrocal, Extremera, & Ramos, 2004). Specifically, they filled in this 24-item questionnaire that identifies three intrapersonal factors: emotional clarity, emotional repair, and emotional attention. Emotional clarity refers to an individual’s tendency to discriminate their own emotions and moods (8 items, e.g., “I often perceive my feelings clearly”); emotional repair refers to an individual’s tendency to regulate their own feelings (eight items, e.g., “Although I am sometimes sad, I generally have an optimistic viewpoint”); emotional attention conveys the degree to which an individual tends to observe and think about his/her own feelings and moods (eight items, e.g., “I think it is not worth paying attention to your own emotions or moods”). Cronbach’s alpha was .90 for emotional clarity, .86 for emotional repair, and .86 for emotional attention. 2. Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS, Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988). This instrument is comprised by 20 items in a rating scale of 5-point Likert scale. Affect is measured in two dimensions: positive and negative. PA reflects the extent to which a person feels enthusiastic, active, alert, energetic and rewarding participation. NA is a general dimension of subjective distress and unpleasant involvement including a variety of aversive emotional states such as disgust, anger, guilt, fear and nervousness. We used the Spanish version of the scale with a Cronbach´s alpha of .89 (PA) and .91 (NA) for men and .87 (PA) and .89 (NA) for women (Sandín, Chorot, Lostao, Joiner, Santed, & Valiente, 1999). 3. MBI Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach & Jackson, 1986). Spanish version by Seisdedos (1997). On 6-point scales individuals answered to 22 items referred to attitudes, emotions and personal feelings of the professional about his/her work and the people they have to attend. This scale measures the three characteristically dimensions of burnout syndrome: emotional exhaustion (EE) defined as wear, loss of energy, exhaustion and fatigue; it may be manifested physically and/or psychologically; depersonalization (D) that refers to the negative attitude towards individuals, especially beneficiaries of their work, accompanied by irritability and low motivation; and personal accomplishment (PAC) that refers to negative responses to self and to work, typical of depression, low morale, avoidance of interpersonal relationships and poor self-esteem. A person would have burnout if scoring high on EE and D, whereas scores in PAC would be low. With regard to psychometric characteristics, Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficient was .83 for EE, .48 for D, and .77 for PAC. 158 Augusto-Landa, López-Zafra, Berrios-Martos, and Pulido-Martos Results Descriptive analysis See table 1 for means, standard deviations and alpha of Cronbach for the different variables of the study. Table 1 Means, Standard Deviations and Cronbach´alpha of Subescales of Trait MetaMood Scale, The PANAS Scales of Positive and Negative Affect and Maslach Burnout Inventory M SD Cronbach´alpha Attention 23.30 6.22 .88 Clarity 27.06 5.51 .88 Repair 26.71 5.31 .80 Negative affect 20.17 8.25 .92 Positive affect 32.40 8.11 .91 18.63 10.70 .78 Scales / subscales TMMS PANAS MBI Emotional exhaustion Depersonalisation 8 6.68 .69 Personal accomplishment 32 10.76 .87 Note: TMMS= Trait Meta Mood Scale; PANAS= Positive and Negative Affect Scale; MBI= Maslach Burnout Inventory. Correlational Analysis See table 2 for Pearson correlations between the variables of the study. Pearson correlation coefficients range from .02 to .73. Regarding the relationships among PEI dimensions (attention, clarity and repair) a significant positive relation was found between emotional clarity and repair, and between emotional attention and clarity. The relationship between emotional attention and emotional repair was not significant. For the burnout dimensions, as expected, EE and D showed a positive correlation, whereas PAC was negatively correlated to EE and D. NA only showed significant relations with burnout dimensions. Specifically, NA was positively related to EE and D and negatively to PAC. As expected, NA has a negative relation with positive affect. PA showed significant relations with the three 159 Perceived emotional intelligence, affect balance and burnout Table 2 Correlations between measures 1 1. Attention 2 3 4 5 6 7 - 2. Clarity .20** - 3. Repair .01 .35** - 4. Negative affect .11 -.05 .05 - 5. Positive affect .19** .22** .19** -.59** - 6. Emotional exhaustion .23** .07 .06 .52** -.35** - -.05 -.05 -.02 .63** -.56** .46** .23** .23** .13* -.53** .73** -.18** -.56** 7. Depersonalization 8. Personal accomplishment - Note: **p< .01, *p< .05 PEI dimensions. It also showed significant negative relationships with EE and D, and positively with PAC. Structural equation modeling (SEM) First, we carried out analysis for the detection of errors and omissions in the data. We opted for the use of a simple imputation for missing values, replacing them with the participant´s average score on that dimension. For all variables the total number of missing values was less than 5% so that the imputation raised no concerns for the analysis (Graham, 2009). SEM was used to test the hypothesized theoretical model fit (see Figure 1). Covariance matrices were analyzed using the AMOS software. The EQS 6.1 software was used to calculate the robust adjustment indices. The estimation method used was the maximum likelihood method. The evaluation of the adequacy of the global model was based on the use of measures of absolute fit, incremental fit and parsimony. Specifically, a chi-square Satorra-Bentler, and the root mean-square error of approximation (RMSEA). In comparing the hypothesized model with the null model we used the following incremental adjustment measures: the normative fit index (NFI) and the comparative fit index (CFI). The parsimony index used was the parsimony goodness-of-fit index (PGFI). For the CFI, NFI, and GFI values greater than .90 indicate an acceptable fit (Bentler, 1990). The PGFI has expected values in the .50s (Mulaik et al., 1989) and for the RMSEA, values of .08 (Gierl & Rogers, 1996) or below indicate a reasonable fit of the model. The data analysis indicated the absence of multivariate normality, reporting on robust indicators of model fit (specifically the Satorra-Bentler χ2 corrected index and CFI) that allow controlling non-normality of the data (Kline, 1998). In the analysis of initial hypothesized fit of the model a χ2Satorra-Bentler (16)= 107.81, p<.001 is obtained, indicating an improper fit of the model. Following the 160 Augusto-Landa, López-Zafra, Berrios-Martos, and Pulido-Martos Figure 2 Standard estimations for the new model introducing the changes on the hypothesized model Note: * p< .05, ** p< .01, *** p< .001 recommendations of Wheaton (1978), who advises against making decisions about the fit of the model based solely on the chi-square statistic, we reviewed the other indexes. The values obtained were: CFI= .86, NFI= .84, GFI= .94, AGFI= .85, PGFI= .41, RMSEA= .12. Following the guidelines of Hu and Bentler (1999), most of the indicators obtained recommend modification of the original model for a better fit according to the data. First, we remove the paths with not significant coefficients. Specifically, we eliminate the path between emotional clarity and positive affect. On the other hand, after reviewing the standardized residual covariance matrix, following the approach of Jöreskog and Sorbom (1988), we establish a relationship between the emotional attention and emotional exhaustion. Finally, by analyzing the rates of change, we establish relations between the emotional attention and PAC, and between the emotional clarity and PAC. The new model also introduces a correlation between error terms of two dimensions of burnout, that when the same construct dimensions do not affect the whole analysis, specifically between the error terms of EE and PAC. The other coefficients and relationships are kept getting a second model for which were carried out further calculations. Figure 2 shows the standardized estimates for the new model. The overall fit of the new model improved as new indexes from the analyses yielded. The Satorra-Bentler χ2 (16)= 82.42, p<.001 was statistically significant. However, the other indices supported the new model changes: CFI= .90, NFI= .95, GFI= .97, AGFI= .92, PGFI= .38, RMSEA= .07. No index indicated that a new adjustment could improve the model. Overall the model accounts for the 37% of the EE variance, a 57% for D, and a 67% for PAC. The model explained, together, the 80% of the latent burnout varia- Perceived emotional intelligence, affect balance and burnout 161 ble. The regression weights of all factors are significant except for clarity-personal accomplishment. However, given that the final adjustment of the model is good, we decided to maintain this relationship for a better comprehension of the overall results. Discussion Our objectives are thus fulfilled. We investigate the relationship between PEI and burnout in primary school teachers, and at the same time, we examine the mediating effects of PA between PEI and dimensions of burnout using a structural equation model. Regarding the averages found in the dimensions of the MBI, they are similar to those found in other Spanish studies with similar samples. Thus, our mean in EE is of 18.63, whereas for Extremera, Duran and Rey (2010) is of 19.51 and for Pena and Extremera (in press) is of 19.26. As for the Depersonalization our average was 8, Extremera et al. (2010) was 4.82 and Pena and Extremera (in press) is 4.2, that is, our average doubled the ones found in other Spanish studies. As for PAC our mean was 32 whereas for Extremera et al. (2010) was 36.54 and for Pena and Extremera (in press) was 38.16. Comparing our scores with the profiles of primary school teachers attending the normative Spanish sample of the MBI (Gil-Monte & Peiró, 2000), we can assert that our study and the other two above mentioned studies regarding the EE show average levels. Regarding the D dimension our sample exhibits a high level compared to a medium level shown by the studies listed above. Finally, regarding the PAC dimension our sample shows lower levels than the two other studies. Differential personality traits (such as PA and NA) may decrease or increase the impact of the presence or absence of burnout in teachers. Thus, studies have shown the predictive capacity of the affect balance on various vital aspects of the subject's life. For example, Augusto et al. (2006) showed the predictive power of PA on the components of burnout (EE and D) and of PA on the PAC beyond the prediction of socio-demographic variables and EI. Other studies have examined the mediating role of affect balance and PEI on life satisfaction. Palomera and Brackett (2006) analyzed the need to control the PA and NA independently (as well as differentiating between intensity and frequency) in studies about the incremental validity of PEI. As mentioned above, PEI components (attention, clarity and emotional repair) show a direct effect on the components of burnout. Thus, some studies have shown the direct relationship between emotional attention and EE, D and PAC (Augusto et al., 2006), emotional clarity and PAC (Extremera & Fernández-Berrocal, 2003; Extremera and et al., 2010, Durán et al., 2004). Also studies have shown the direct impact that EI has on balance of the emotions, and found a direct relationship between the emotional attention, clarity and repair with PA (Gohm & Clore, 2002; Gallaguer, 2008; Kafetsios & Zampetakis, 2008, Laborde, Dosseville, & Scelles, 2010). Futhermore, we have found direct links between the components 162 Augusto-Landa, López-Zafra, Berrios-Martos, and Pulido-Martos of emotional balance and burnout components. Studies have shown positive relations between NA and EE and D (Moya-Albiol et al., 2005; Thoresen, Kaplan, Barsy, Warren, & CHermot, 2003), negative relations between PA and EE (Thoresen et al. 2003), and D (Moya-Albiol et al., 2005) and positive relations to PAC (Brackett et al., 2010). This study contributes to knowledge in several ways. First, we propose a model in which mediational relations are established in a comprehension model that states the relations among variables. Although we expected that the three dimensions of the PEI would influence on burnout (as reported in the model as a latent variable) through positive affect, it is PA the dimension that mediated completely the effect of emotional repair on burnout dimensions, whereas the mediation of emotional attention was partial. Emotional attention directly influenced EE and PAC, along with the PA mediation effect. Emotional clarity influences PAC as shown in the model (although the regression coefficient is not significant). Our results are in agreement with those of Brackett et al. (2010) that conclude about the importance of PA as a mediator variable between emotional regulation (as measured by MSCEIT) and PAC. The authors suggest in their model, a direct effect of emotional repair on burnout dimensions. Secondly, we predicted that negative affect would account for the burnout variance. And effectively, NA showed a positive relationship with EE and D while showing a negative relationship with PAC. Furthermore, NA accounted for part of the variance of these three factors of burnout. Thus, teachers who show aversive emotional states, negative and pessimistic attitudes report more emotional exhaustion and depersonalization and lower personal accomplishment. Indeed, in our study, negative affect was established as the biggest predictor of burnout in teachers. Moya-Albiol, Serrano, González-Bono, Rodríguez-Alarcón and Salvador (2005) point out that PANAS´ scores reflect different aspects, as the PA reflects a cognitive state, while the NA would be emotional. According to the authors, in a working day the teachers suffer a worsening of negative affect and greater self-perceived stress. Likewise, they found positive relationships between negative affect and total burnout. Thirdly, as expected our model includes the relations among PEI dimensions as in previous Studies. Thus, positive relations between emotional attention and clarity as well as between emotional repair and clarity are shown. In sum, our results have mainly shown that emotional repair has a role to avoid burnout in teachers. In this same line, the study carried out by Marin, Teruel and Bueno (2006) highlighted the crucial role that EI plays for teaching students in emotional skills, considering them very important in their training over academic training and experience. Therefore, the development of skills in emotional clarity and emotional repair will be fundamental as a way of coping with the academic work. Taking into account all the above, our results point out the importance of the practical implications with Mayer and Salovey´s model as a base. Emotional competencies may be trained in teachers. Training emotional attention consists firstly in recognizing emotional states to therefore predict behavior and thoughts. In this training the aim is to examine and identify emotions. The use of emotions implies Perceived emotional intelligence, affect balance and burnout 163 to know how the emotions act on our thinking and the way we process information. Thus, the aim of this training would consist of encouraging teachers to explore how different messages (egr. television commercials) affect our emotions to lay the groundwork for thinking a particular way about themselves and the message (eg. products or services they bid). Training in emotional comprehension implies to increase the ability to understand emotions and emotional knowledge to use. One way to develop a better understanding of the causes of certain emotions is through the analysis of events, people and situations, reflecting afterwards on what it is evoked at an emotional level. Finally, to reach emotional repair individuals have to be good at understanding of emotions and the learn how to manage and handle with their emotions. There are several implemented programs at date based on the model of Mayer and Salovey (1997). In Belgium Nelis, Quoidbach, Mikolajczak, & Hansenne (2009) and Brackett, Alster, Wolfe, Katulak, & Fale (2007) in the United States, have developed these programs. In Spain the main references are the Botin Foundation in Santander, and the research group lead by Fernandez-Berrocal in Malaga who are implementing these programs in Guipuzcoa, Catalonia and Malaga indicating the benefits obtained in the EI training. Despite our promising findings, this study has several limitations that should be taken into account in future research. Data were cross-sectional and represent a specific sample. It would be desirable to carry out research on other samples of teachers (e.g. from other provinces) and to consider longitudinal studies to accurately examine the causal effects of emotional deficit on teachers’ occupational stress. It would also be of great interest to use performance tests such as the MSCEIT to examine differences in results with respect to self-reports in relation to burnout. References Aguilar Luzón, M. C., & Augusto Landa, J. M. (2009). Relación entre inteligencia emocional percibida, personalidad y capacidad empática en estudiantes de enfermería. [The relationship between perceived emotional intelligence, personality traits and empathy in nursing students]. Behavioral Psychology/Psicología Conductual, 17, 351-364. Antoniou, A. S., Polychroni, F., & Vlachakis, A. N. (2006). Gender and age differences and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103, 103-116. Augusto Landa, J. M., Berrios-Martos, P., López-Zafra, E., & Aguilar Luzón, M. C. (2006). Relación entre burnout e inteligencia emocional y su impacto en la salud mental, bienestar y satisfacción laboral en profesionales de enfermería. [Relationship between burnout and emotional intelligence and its influence on mental health, well-being and work satisfaction among nursing proffessionals]. Ansiedad y Estrés, 12, 479-493. Augusto Landa, J. M., López-Zafra, E., Berrios Martos, M. P., & Aguilar Luzón, M. C. (2008). The relationship between emotional intelligence, occupational stress and health in nurses: a questionnaire survey. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45, 88-901. Augusto Landa, J. M., López-Zafra, E., Martínez de Antoñana, R., & Pulido Martos, M. (2006). Perceived emotional intelligence and life satisfaction among university teachers. Psicothema, 18, 152-157. 164 Augusto-Landa, López-Zafra, Berrios-Martos, and Pulido-Martos Augusto Landa, J. M., Pulido Martos, M., & López-Zafra, E. (2011). Does perceived emotional intelligence and optimism/pessimism predict psychological well-being? Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 463-474. Augusto Landa, J. M., López-Zafra, E., & Pulido, M. (2011). Inteligencia emocional percibida y estrategias de afrontamiento al estrés en profesores de enseñanza primaria: propuesta de un modelo explicativo con ecuaciones estructurales (SEM). [Perceived emotional intelligence and stress coping strategies in primary school teachers: Proposal for an explanatory model with structural equation modelling (SEM)]. Revista de Psicología Social, 26, 413-426. Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238-246. Betoret, F. D. (2006). Stressors, self-efficacy, coping resources, and burnout among secondary school teachers in Spain. Educational Psychology, 26, 519-539. Brackett, M. A., Alster, B., Wolfe, C., Katulak, N. & Fale, E. (2007). Creating an emotionallyintelligent school district: a skill-based approach. In R. Bar-On, J. Jacobus, G. Maree, & M. J. Elias (Eds.), Educating people to be emotionally intelligent (pp. 123-137). Wesport, CT: Praeager. Brackett, M. A., Palomera, R., Mojsa, J., Reyes, M. R., & Salovey, P. (2010). Emotion regulation ability, burnout and job satisfaction among secondary school teachers. Psychology of Schools, 47, 406-417. Brock, B. L., & Grady, M. L. (2002). Avoiding burnout: a principals’ guide to keeping the fire alive. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin. Burke, R. J., Greenglass, E. R., & Schwarzer, R. (1996). Predicting teacher burnout overtime: effects of work stress, social support, and self-doubts on burnout and its consequences. Anxiety, Stress and Coping: An International Journal, 9, 261-275. Cano-García, E. J., Padilla-Muñoz, E. M., & Carrasco-Ortiz, M. A. (2005). Personality and contextual variables in teacher burnout. Personality and Individual Differences, 38, 929940. Carlotto, M. S. (2002). A síndrome de burnout e o trabalho docente. Psicologia em Estudo, 7, 21-29. Clark, D. A., Beck, A. T., & Stewart, D. (1990). Cognitive specificity and positive-negative affectivity: complementary or contradictory views on anxiety and depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology 99, 148-155. Clark, L. A., Watson, D., & Mineka, S. (1994). Temperament, personality, and the mood in occupational stress and professional burnout between primary and high-school teachers in Greece. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21, 682-690. Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71-75. Durán, A., Extremera, N., & Rey, L. (2004). Self-reported emotional intelligence, burnout and engagement among staff in services for people with intellectual disabilities. Psychological Reports, 95, 386-390. Extremera, N., Durán, M. A., & Rey, L. (2007). Inteligencia emocional y su relación con los niveles de burnout, engagement y estrés en estudiantes universitarios. [Emotional intelligence and its relationship with the levels of burnout, engagement and stress in University students]. Revista de Educación, 342, 239-256. Extremera, N., Durán, M. A., & Rey, L. (2010). Recursos personales, síndrome de estar quemado por el trabajo y sintomatología asociada al estrés en docentes de enseñanza primaria y secundaria. [Personal resources, burnout and symptoms associated with stress in primary and secondary teachers]. Ansiedad y Estrés, 16, 47-60. Perceived emotional intelligence, affect balance and burnout 165 Extremera, N., Fernández-Berrocal, P., & Durán, M. A. (2003). Inteligencia emocional y burnout en profesores. [Emotional intelligence and burnout in teachers]. Encuentros en Psicología Social, 1, 255-259. Extremera, N., Fernández-Berrocal, P., Ruiz-Aranda, D., & Cabello, R. (2006). Inteligencia emocional, estilos de respuesta y depresión. [Emotional intelligence, responses styles and depression]. Ansiedad y Estrés, 12, 191-205. Extremera, N., Rey, L. & Pena, M. (2010). La docencia perjudica seriamente la salud: análisis de los síntomas asociados al estrés docente. [The teaching harms the health seriously. Analysis of the symptoms associated to the educational stress]. Boletín de Psicología, 100, 43-54. Extremera, N., Salguero, J. M., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2011). Trait meta-mood and subjective happiness: a 7-week prospective study. Journal of Happiness Studies, 12, 509-517. Fernández-Berrocal, P., Extremera, N., & Ramos, N. (2004). Validity and reliability of the Spanish modified version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychological Reports, 94, 751755. Fernández-Berrocal, P., & Ruiz-Aranda, D. (2008). La inteligencia emocional en la educación. [Emotional intelligence in education]. Revista de Investigación Psicoeducativa, 6, 193204. Freudenberger, H. J. (1974). Staff burn-out. Journal of Social Issues, 30, 159-165. Friedman, I. (2000). Burnout in teachers: shattered dreams of impeccable professional performance. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56, 595-606. Gara, M. A., Woolfolk, R. L., Cohen, B. D., Goldston, R. B., Allen, L. A., & Novalany, J. (1993). Perception of self and other in major depression. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102, 93-100. Gierl, M. J., & Rogers, T. (1996). A confirmatory factor analysis of the test anxiety inventory using Canadian high school students. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 56, 315-324. Gil-Monte, P., & Peiró, J. M. (2000). Un estudio comparativo sobre criterios normativos y diferenciales para el diagnóstico del síndrome de quemarse por el trabajo (burnout) según el MBI-HSS. [A comparative study on normative criteria and differential diagnosis of the syndrome of burning the work (burnout) according to the MBI-HSS]. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 16, 135-149. Gohm, C. L., & Clore, G. L. (2002). Four latent traits of emotional experience and their involvement in attributional style, coping and well-being. Cognition and Emotion, 16, 495-518. Graham, J. W. (2009). Missing data analysis: making it work in the real world. Annual Review of Psychology, 60, 549-576. Hakanen, J. J., Bakker, A. B., & Schaufeli, W. B. (2005). Burnout and work engagement among teachers. Journal of School Psychology, 43, 495-513. Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cut-off criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. Jennett, H. K., Harris, S. L., & Mesivov, G. B. (2003). Commitment to philosopy, teacher efficacy, and burnout among teachers of children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 33, 583-593. Kafetsios, K., & Zampetakis, L. A. (2008). Emotional intelligence and job satisfaction: testing the mediatory role of positive and negative affect at work. Personality and Individual Differences, 44, 710-720. Kline, R. B. (1998). Principals and practice of structural equation modelling. New York: Guilford. 166 Augusto-Landa, López-Zafra, Berrios-Martos, and Pulido-Martos Kluemper, D., Little, L., & DeGroot, T. (2009). State or trait: effects of state optimism on job-related outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30, 209-231. Kokkinos, C. M. (2007). Job stressors, personality and burnout in primary school teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77, 229-243. Laborde, S., Dosseville, F., & Scelles, N. (2010). Trait emotional intelligence and preference for intuition and deliberation: respective influence on academic performance. Personality & Individual Differences, 49, 784-788. Limonero Garcia, J., Gómez Benito, T., Tomás Sábato, J., & Fernández Castro, J. (2004). Influencia de la inteligencia emocional percibida en el estrés laboral de enfermería. [Influence of perceived emotional intelligence in nursing work stress]. Ansiedad y Estrés, 10, 29-41. Manassero, M. A., Vázquez, A., Ferrer, V. A., Fornés, J., & Fernández, M. C. (2003). Estrés y burnout en la enseñanza. [Stress and burnout in the teaching]. Palma de Mallorca: Edicions UIB. Marqués-Pinto, A., Lima, M. L., & Lopes da Silva, A. (2005). Fuentes de estrés, burnout y estrategias de coping en profesores portugueses. [Sources of stress, burnout and coping strategies in Portuguese teachers]. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 21, 125-143. Martínez, I. M., Grau, R., & Salanova, M. (2002). El síndrome de burnout en profesionales de la educación. [The burnout syndrome in professional education]. In M. Marín, R. Grau, & S. Yubero (Eds.), Procesos psicosociales en los contextos educativos (pp. 187-196). Madrid: Pirámide. Martins, A., Ramalho, N., & Morin, E. (2010). A comprehensive meta-analysis of the relationship between emotional intelligence and health. Journal of Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 554-564. Maslach, C. (1977). Burnout: a social psychosomatic analysis. Paper Presented at The Meeting of American Psychological Association, San Francisco. Maslach, C. (1993). Burnout: a multidimensional perspective. In W. B. Schaufeli, C. Maslach, & T. Marek (Eds.), Professional burnout: recent developments in theory and research (pp. 19-32). Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis. Maslach, C., & Jackson, S. (1986). Maslach Burnout Inventory Manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists. (2ª edic.). Mayer, J. D., & Salovey, P. (1997). “What is emotional intelligence?” In P. Salovey, & D. Sluyter (Eds.), Emotional development and emotional intelligence: implications for educators (pp. 3-31). New York: Basic Books. Mayer, J. D., Salovey, P., & Caruso, D. R. (2002). Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT) Item Booklet. Toronto: MHS. Mearns, J., & Cain, J. E. (2003). Relationships between teachers´ occupational stress and their burnout and distress: roles of coping and negative mood regulation expectancies. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 16, 71-82. Mota-Cardoso, R., Araujo, A., Carreira Ramos, R., Gonçalves, G., & Ramos, M. (2002). O stress nos professores portugueses - Estudo IPSSO 2000. [Stress in Portuguese teachers - Study IPSSO 2000]. Porto: Porto Editora. Moya-Albiol, L., Serrano, M. A., González Bono, E., Rodríguez Alarcón, G., & Salvador, A. (2005). Respuesta psicofisiológica del estrés en una jornada laboral. [Psychophysiological stress response in a working day]. Psicothema, 17, 205-211. Mulaik, S. A., James, L. R., Van Altine, J., Bennett, N., Lind, S., & Stilwell, C. D. (1989). Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin, 105, 430-445. Perceived emotional intelligence, affect balance and burnout 167 Nelis, D., Quoidbach, J., Mikolajczak, M., & Hansenne, M. (2009). Increasing emotional intelligence: (How) is it possible? Personality and Individual Differences, 47, 36-41. Palomera, R. & Brackett, M. (2006). Frecuencia del afecto positivo como posible mediador entre la inteligencia emocional percibida y la satisfacción vital. [Frequency of positive affect as a possible mediator between perceived emotional intelligence and life satisfaction]. Ansiedad y Estrés, 12, 231-239. Pena, M., & Extremera, N. (in press). Inteligencia emocional percibida en profesorado de primaria y su relación con los niveles de burnout e ilusión por el trabajo (engagement). [Perceived emotional intelligence in primary school teachers and its relation with the levels of burnout and engagement]. Revista de Educación, 359. Platsidou, M. (2010). Trait emotional intelligence of Greek special education teachers in relation to burnout and job satisfaction. School Psychology International, 31, 60-76. Salanova, M., Schaufeli, W. B., Llorens, S., Peiró, J. M., & Grau, R. (2000). Desde el ‘burnout’ al ‘engagement’: ¿una nueva perspectiva? [From the 'burnout' to 'engagement': a new perspective?]. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y las Organizaciones, 16, 117-134. Salovey, P., Mayer, J. D., Goldman, S., Turvey, C., & Palfai, T. (1995). Emotional attention, clarity and repair: exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. In J. W. Pennebaker (Ed.), Emotion, disclosure, and health (125-154). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. Salovey, P., Stroud, L. R, Woolery, A., & Epel, E. S. (2002). Perceived emotional intelligence, stress reactivity and symptom reports: furthers explorations using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychology and Health, 17, 611-627. Sandín, B., Chorot, P., Lostao, L., Joiner, T. E., Santed, M. A., & Valiente, R. M. (1999). Escalas PANAS de afecto positivo y negativo: validación factorial y convergencia transcultural. [The PANAS Scales of Positive and Negative Affect: Factor analytic validation and crosscultural convergence]. Psicothema, 11, 37-51. Schaufeli, W. (2005). Burnout en profesores: una perspectiva social del intercambio. [Burnout in teachers: a social exchange perspective]. Revista de Psicología del Trabajo y de las Organizaciones, 21, 15-36. Schutte, N. S., Malouff, J. M., Hall, L. E., Haggerty, D. J., Cooper, J. T., Golden, C. J., & Dornheim, L. (1998). Development and validity of a measure of emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 25, 167-177. Seisdedos, N. (1997). MBI. Inventario «Burnout» de Maslach: manual. [MBI. Inventory "Burnout" Maslach: manual]. Madrid: TEA. Skaalvik, E. M., & Skaalvik, S. (2007). Dimensions of teacher self-efficacy and relations with strain factors, perceived collective teacher efficacy, and teacher burnout. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99, 611-625. Thoresen, C. J., Kaplan, S. A., Barsky, A. P., Warren, C. R., & de Chermont, K. (2003). The affective underpinnings of job perceptions and attitudes: a meta-analytic review and integration. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 914-945. Van Horn, J. E.; Schaufeli, W. B.; Greenglass, E. R., & Burke, R. J. (1997). A Canadian-Dutch comparison of teachers’ burnout. Psychological Reports, 81, 371-382. Vandenberghe, R., & Huberman, A. M. (1999). Understanding and preventing teacher burnout: a sourcebook of international research and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University. Watson, D., & Clark, L. A. (1997). Extraversion and its positive emotional core. In R. Hogan, J. Johnson, & S. Briggs (Eds.), Handbook of personality psychology (pp. 767-793). San Diego, CA: Academic Press. 168 Augusto-Landa, López-Zafra, Berrios-Martos, and Pulido-Martos Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of Positive and Negative Affect: the PANAS Sates. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54, 1063-1070. Wheaton, B. (1978). The sociogenesis of psychological disorder. American Sociological Review, 43, 383-403. Wong, C. S., & Law, K. S. (2002). The effects of leader and follower emotional intelligence on performance and attitude: an exploratory study. The Leadership Quarterly, 13, 243274. Zellars, K. L., Hochwarter, W. A., Perrewe, P. L., Hoffman, N., & Ford, E. W. (2004). Experiencing job burnout: the roles of positive and negative traits and states. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 34, 887-911. Zevon, M. A., & Tellegen, A. (1982). The structure of mood change: an idiographic/ nomothetic analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 43, 111-122. Recibido: April 1, 2011 Aceptado: December 1, 2011